Recovering control of our food

- Where has what we eat come from? Produced by whom and how? More and more initiatives are being taken to ensure a healthy diet based on indigenous agriculture. We have had the experience of two of them and we have had a very interesting interview with Mixel Berhokoirigoin, president of the Basque Country House of Agriculture.

“All farmers in the world have the right to produce their country’s food under local conditions – with the form of local cultivation, customs and possibilities – and within the framework of the local political project. Therefore, we also have the right to supply the food of our people in the Basque Country”. These are the words of Mixel Berhokoirigoin, president of the Basque Country Chamber of Agriculture. Indeed, encouraged by this right and implementing the claim, a number of dynamics and projects have recently been launched.

BasHerri: local producers and consumers

EHNE and the organic farming association Biolur jointly launched the BasHerri movement in Gipuzkoa. It has a clear objective, to regain control of food, that is, to decide what we want to eat, knowing who, where, how and under what conditions they occur. To do so, they support the path of agroecology. “The agricultural model we seek from the BasHerri movement is the one that responds to the needs of society and respects nature, a sustainable agriculture linked to land and people,” said Pedro Alberdi, coordinator of the movement and member of the EHNE union.

Local producers – the baserritars – are responsible for producing organic products, and consumers are local citizens. These consumer groups operate through direct sales and take the form of an exchange that meets the needs of the citizens and the garbage collectors: The baserritarra prepares a basket of seasonal products (vegetables, fruits, bread, eggs, milk, chicken, jam, cider…) that it produces weekly and brings the members of the group, the population, in a given place and at a given time. Each family determines its consumption according to its needs (whole or half basket), thus setting the monthly quota. “Instead of establishing a power relationship between the baserritars and the citizenry, ‘I pay you and I ask you’, they go at once and have a direct relationship,” Alberdi stressed.

The channels used to work this close contact are diverse: visits to the farmhouses, monthly meeting (to talk about the situation of the vegetable garden, the incidences arising in the production, recipes, new members or products…), auzolanes, BasHerri meetings, courses and days. “Every three months my peers come to my vegetable garden and not only see where what they eat comes from, but they sow something,” explains Harkaitz Portularrume, Usurbil’s baserritarra involved in the movement. Two years ago, animated by her wife and taking advantage of the fact that a friend had land, she started working in the garden. It has extensive land in the Aginaga district of Usurbil, where many products of the time can be found. Currently, it has two groups in Donostia-San Sebastian, in which it serves more than 50 families.

Closeness, trust and commitment

The consumer group is not just a marketing model, it has a whole philosophy behind it. In Alberdi’s opinion, “the direct relationship between the baserritarras and the citizenry generates closeness, trust and commitment, and that connection is more effective than any control that may come from the outside”. That is precisely what Portularrume values most. Proof of this is that in November of last year, between floods and subsequent frost, he lost all the products of the orchard and by informing the population that they had not given him any problems and had paid him the same fee, “because they knew that in this situation nothing could be done”.

In Gipuzkoa, the first consumption group, Uztaro, was founded seven years ago in Beizama, based on a cooperative structure. Then came the consumption group of Arrasate three years ago, and since then the direct selling system has multiplied. “We also bring products that we don’t have in our lands, but in these cases we also want them to have a philosophy of direct selling,” explains the EHNE member.

Alberdi has underlined that this is a good opportunity to ensure stability and to attract young people to the sector. “I’ve always liked to buy and consume local food because it guarantees good quality products, and also this system can help ensure the future of the farmhouses,” said Karmele Álvarez, a member of the consumption group in the Donostia neighborhood of Amara. Anyone wishing to participate in the group simply has to contact EHNE.

“Through consumer groups we want to claim that healthy food and local agriculture do not have to be luxury and that eating good quality food is a right that we have all citizens,” says Alberdi. Other areas, such as the promotion of fairs or the supply of local products in the city's dining rooms, should also continue to be affected. An example of this is the experience that has been set in motion in the Larrabetzu dining room (see No. 2225 of Luz).

Baserri Barri, from Aramaio for the Aramaioarras

In Álava, the Baserri Barri (ABB) project in Aramaio has been developing for five years. The rural development initiative was born with the objective of promoting local products and meeting the needs of the population. The apple was the one that started the movement. In order to take advantage of the waste, several baserritarras joined the Association of Aramaio Cider Lovers (ASE) and bought the necessary machinery to improve the quality and increase the quantity of the product, and they dedicated themselves to the elaboration of juice and cider. Other baserritars, including farmers, milk producers and farmers, joined the initiative of cider lovers. Currently, the initiative has the direct participation of about 50 people (about 1,500 inhabitants in Aramaio), although indirectly almost all of the people’s agents, including the City Hall itself, are involved.

With the main objectives, Aitor Larrañaga, dynamising the Baserri Barri project, has raised the issue of food sovereignty. “We want to gradually regain the food sovereignty of the Aramaioarras.” Thus, they have taken advantage of domestic production in almost all dwellings, mostly natural (fresh and processed vegetables, fruit, milk, cheese, bread, honey…) and have decided to keep the habit of producing home food for the home. For the future, it is intended to increase production so that aramaioarras who lack the means to produce food can also have local food. The City Hall provides the baserritars with the necessary infrastructure for their work. In addition to guaranteeing food sovereignty, the objective is to work on energy sovereignty and to recover the heritage of Aramaio.

Faced with industrialization, they have managed to keep alive the culture of the farmhouse in the Alavese locality, knowing that the rural environment has a lot to offer. “It is a project based on the socio-economic situation in which we live the Aramaioarras. It can serve as an example for other peoples, but each one should develop an initiative tailored to their situation,” Larrañaga says. They have had, precisely, examples of the experiences of the surrounding peoples, such as Zerain, Eztango-Itsaso, Beizama and Lastur.

Baserri Barri has had an excellent reception in the people and also outside it. A sign of this are the visits they have received from the surrounding peoples, “what awakens the self-esteem and the desire to work of the citizens”, has acknowledged the dynamizing. “The free market that prevails today has led us to bring out the products we can create in it and that directly affects our economy. Proper exploitation of the resources available in Aramaio allows us, in addition to meeting our needs, to create local jobs and strengthen the local economy.” Larrañaga also believes that times of crisis are good at realizing all this and creating real alternatives by working on new ideas. In short, all these alternatives remind us that in order to care for ourselves and guarantee our future it is essential to take care of land, animals and food.

Mixel Berhokoirigoin: President of the Basque Country Chamber of Agriculture

“Food sovereignty means achieving as much autonomy as possible for a society”

Mixel Berhokoirigoin (Gamarte, Nafarroa Beherea, 1952) is one of the references of agriculture in the French Basque Country. One of the founders of the ELB trade union and from its creation to the present president of the Basque Country Herriko Laborantza ganbara (EHLG). He was also general secretary of Confederation Paysann and member of Vía Campesina. We have reflected with them on food sovereignty.

What variables does food sovereignty take into account?

If food sovereignty is to be an alternative, it must be shared from general perspectives and concepts. Local food sovereignty is first and foremost linked to agricultural policy and currently most policies, particularly in the more advanced countries, are based on the concept of free market established by the OECD: where no barriers to trade are placed, products are liberalised and production is located around the world, without taking into account local social problems and conditions. That is liberalisation, and the current European agricultural policy is in this picture. 50 years ago, European agricultural policy was aimed at feeding the inhabitants of its area, but when that was achieved (20 years ago) it was thought that Europe should change course and act on world markets, so a process of liberalisation took place. And this goes against food sovereignty; the organization of production and cultivation on the basis of world markets means that industrial quantities must enter the production that is being produced, which implies the specialisation of each world country and the uniformization of all kinds of food. In order to achieve this, cultivation must be industrialised.

On the contrary, food sovereignty means that in each area a diversity – not specialisation – must be achieved, the food that the local inhabitants need. Therefore, the need for the local population is a priority and not the one demanded by a local market. It also brings producers and consumers closer together, shortening the distance between them. Therefore, this implies responsibility in the model and the quality of production. Instead, if you make a production for an anonymous world market and for consumers you don't know, you don't know what the outcome of your work is. Therefore, the action of making food is dehumanized, the responsibility is removed and the farmer is removed from his basic functions.

Food sovereignty can be raised in different ways: a state applying standards, or working in a self-managed and autonomous way by towns or neighborhoods. Which model do you lean to?

We need both. There is a political picture that sets out laws and no one can be taken out of the conditions it imposes. It is true that it is possible to build an alternative – with certain conditions in certain places – but I believe that it will always be a minority. If we want food sovereignty to be a global alternative for all, the first thing we have to do is change the political picture. And the first thing is to recognize that every country has the right – without coerage – to feed local people through local products, and that is a priority over products coming from outside. That means, therefore, that this political picture must make it possible to take care of the products coming from abroad and to limit the competences. As a matter of fact, local productions are reduced or diminished with outward production. The most developed areas of the world, from the point of view of agricultural production, sell on world markets products that do not need – in some cases at lower prices – and cannot keep crops and farmers in other countries alive, as well as change their eating habits. Thus, then the inhabitants ask for products from outside. However, if a country is strong in a number of productions it does not mean that it can be aggressive with another country. It is not possible to demand rights for itself and, in the meantime, to be aggressive with other countries.

Food sovereignty is therefore the first political condition and that right must be recognized as a concept at international level. However, there are other technical conditions such as logistics, research, development, experimentation, production systems must be adapted to the local ecosystem, to the climate and to the land, seeds, animals and plants must join the earth… This means that overall food sovereignty is based on diversity, because it requires an adapted agriculture that takes into account the races, the varieties, the plants... The need for this has been reflected in the experience from generation to generation, although in the name of liberalisation and the world market and specialisation has sought to break with it.

As for the production model, local agroecology must be adapted to the conditions and this must be placed in sustainable cultivation. Not all lands have the same capacity, but that does make it clear that the lands of the most hungry countries are not necessarily the poorest. The political picture sets the difference between the two.

Just as liberal trade has its bases and conditions, the one based on food sovereignty must have its own political framework, principles, priorities and production systems. In all countries there are possibilities, such as limits, which are not possible or difficult. One of the conditions of sustainable agriculture is to make the most of existing abundances and to economise on the limited nature of the area. In the case of Euskal Herria, what do we have a lot? Mountain and prairies. The form of cultivation and cultivation that we must devise here must therefore make the most of this resource. This does not mean that exchange should not be given, because exchange is one of the pillars of autonomy.

Speaking of autonomy, would I say that society acquires autonomy through food sovereignty?

Food sovereignty means achieving as much autonomy as possible for a society, but given that not all autonomy is possible and may not need to be sought. It is also autonomy for each country to decide what exchange it wants with the other. It is not about living inside a wall and isolated from the world economically. Basically, autonomy is based on prioritizing the potentials that we have here -- and adapting them to that agro-- and selecting the exchange of products that we need with other countries.

In the North there are two areas: the mountain area that lives around the growth, and in particular the sheep (Doniath-Garazi, Baigorri and Zuberoa), and another area that is minor and mainly cerealist (Amikuze, Bidaxune…). As we see in the first area, in the farmland, the farmhouses are not self-sufficient food and they bring food for sheep and cows, in some cases remotely, from northern France. If we go to the area where the cereal is found, one part is consumed there and the other goes to the port of Baiona to go further. Therefore, if there are two things in contradiction, it is clear that there is a need for exchange and participation between the two areas of Iparralde. We have to create a market nearby, in this respect we are working on the rules, and that gives autonomy and added value to the territory. Looking to the future, autonomy in an increasingly liberalized and extensive world is to have security and a possibility of life.

Therefore, in short, food sovereignty is a generalized concept that requires political and technical conditions, to be able to decide the productive model and to be autonomous, as far as possible, every hamlet and, above all, every territory, but always accepting exchanges.

What fields do you work in Iparralde on the line of food sovereignty?

The system that is based on AMAP consumption groups was born ten years ago and is being developed in Iparralde, and will be modified in its form, although the base will remain as it has been so far. The new farmers who are set up spend at least part of their production on direct sales. Direct selling is at the heart of food sovereignty – local consumers, producers and production – but food sovereignty is not just direct selling, but is not the general alternative, in my view. In Iparralde we live in a model of concentrated society, in the cities people are concentrated, so direct selling cannot be done everything, it is not possible either technically or energetically.

In order to achieve food sovereignty, it is necessary to adapt the economic circuits of the territory. Today they are not organized to offer their productions to local consumers, so it is essential to change that structure and relocate the economy. We have started work from the EHLG to that end, and two departments are currently working in that direction. One is making flour to make bread or cakes right here, because all the flour consumed in the North comes from outside. Four years ago we started working on that task, seeing that there is such ambition on the part of the people, and so we've started to master the techniques of making local flour. The result will be the bread of Euskal Herria.

The second line of work is beef da.Hemen, about 80% of the meat we consume comes from outside, and about 80% of the production goes abroad; economic circuits, cooperatives and businesses are organised accordingly. So we've decided to make a beef circuit: create, raise and kill the animal here. We will also establish a number of regulations for the breeding of this animal. Some farmers who have cows sell meat directly on sale, but if we organize the circuit, it will be others who sell through this circuit.

Sometimes, however, local products are more expensive than those coming from outside. Is that not a hindrance for the consumer to wager on the local?

It is true that local products are sometimes more karyotic than those entering the outside world, for example, cows enter very cheap from Germany and Argentina. Everything has its advantages and disadvantages, but it must, in general and in the long run, be positive. It is very important that production is not too expensive for the consumer when it comes to direct sales, always guaranteeing quality. We have to find the balance: we have to live with our work, but not enter into speculation. What we do must be accessible to the consumer, it must not be for a minority. And it also has to be explained to them that in one thing they buy there are many aspects and that food is one of the pillars of life. In this sense, in recent decades, the money devoted to food has been steadily decreasing. In the French state, for example, people spend on average 15% on food, while in the car they spend more, and I do not know if that makes sense. We need to work on awareness, because every option we make about food is a political choice. We must, however, think carefully about how public money for crops is distributed, as this will have an impact on price, because if the farmer has financial support to develop a sustainable production model, guarantee quality, or develop short circuits, what the consumer has to pay for will be less.

However, being a real alternative can cause the capitalist system to go against you in different ways, as testified by the EHLG issue of two years ago. Are you afraid of those possible attacks? What can be done to combat it?

Economic power, which controls the current organization, will not let the one in his hands escape from his hands, who still has most of the world under control. So it's going to be sokatira, but there's one thing that economic power can't get: to control the choice that people can make individually. I do not believe that industry is going to ban that right or that freedom, because liberalism has a liberal basis. The truth is that it gives me confidence to get right with the opposites.

They'll try to take care of everything they've earned and win other areas where they can, and so they'll win in places where there's no choice or resistance. But if we win a few fields and these are shaped by the ambition of the local people, it will be harder to fight it. Still, I don't think they have too many reasons to worry about, because more than the field they lose is the one they're winning in the world. For example, multinationals behind GMOs (such as Monsanto) have almost everyone colonized. On the other hand, they do business with the problem of hunger, because they present themselves and their strategy to feed all the inhabitants of tomorrow. Why do we see countries in Africa and other countries renting so many lands to multinationals? What we gain from our small experiences, industry wins in many parts of the world. However, there are alternatives such as the Vía Campesina network. While the proposals of capitalism are imposed and centralized, the alternatives are diverse and local. It therefore gives the image of who occupies the world - and the reality is as well - but under that occupation there are alternatives in all places and networks must be built between them.

And when will a culture chamber join the North with the South?

At the moment, for example, we have links with the concept of food sovereignty within the Etxalde movement, where the problems and objectives are the same. It is true that from the South we are seen as a model, but here we have an opportunity that has not been had in the South and that is that there are culture chambers. In the structuring of the French State, the culture chambers play an important role – prominent moral and institutional weight – they are official institutions and have the capacity to receive public money. In addition, the people who make up it are elected by the farmers through elections and therefore have greater legitimacy. Cultivation chambers can manage their competences and decide on agricultural production models (intensive or permanent). We have joined him to make the cabin of agriculture here.

In the South, on the contrary, I believe that on agricultural issues industry is more important – the industrial perspective has prevailed – and it is not thought that a simpler and more workable thing can be done. There are also trade unions, but I do not know to what extent the public authorities take them into account. Then there are specialized and professional structures, but they are vertical, and as an official structure there is a transversal structure that has a global vision. This cross-cutting vision changes the relationship between political power, society and farmers, because political powers cannot do what they like.

Therefore, although we have the same goals in the North and the South, the paths to follow are not the same, because we have different realities: In the North we have to take care of what we have in the field of crops, if we have capital, and in the South we have to revive cultivation and make capital around land and farmers. In the South there are many consumers who can be actors, there is no market problem, so there is a lot to win!

For one day we need to do something together Iparralde and Hegoalde; I do not know whether it will be a growing chamber for the whole of the Basque Country, a federation or a coordination between the growing shrimp. For this, the first thing we have to do is to establish the sovereignty of Euskal Herria and I feel it is possible!

Kontsumo taldeen sistema ez da gaur egun sortua, 1980ko hamarkadan Japonian jarri zuten martxan teikei dinamikaren harira. Japoniara lehenago iritsi zen industrializazioa eta erresistentzia mugimendu gisa eratu zen. Hortik AEBetara egin zuen jauzi mugimenduak, CSA egiturapean (Community Supported Agriculture), eta ondoren Europan finkatu zen. Baserritarrentzat kontsumo taldeak aukera bideragarria direla eta Euskal Herriko baserriaren etorkizuna hor dagoela diote erreportajeko protagonistek.

Dehumanization has penetrated deeply into the powers of the West, and they look with indifference to the holocaust that Gaza is suffering; in Gaza, if bombs do not kill you, you will die of hunger.

Now that our ship has been bombed it is a total impotence, we are well and we... [+]

“Even with all the shortcomings, the unions have done more for humanity than any other human organization that has ever existed. They have contributed more to dignity, honesty, education, collective well-being and human development than any other association of people.” ... [+]

Harri-jasotzearen gorakada nabaritu da azken urteetan, batez ere emakumeen artean. Gazteek harri eskoletan ikasten dute kirolean esperientzia dutenengandik. Crossfit-a, sare sozialak eta telebista faktore garrantzitsuak izan dira kirolaren piztualdian, harri eskolekin batera... [+]

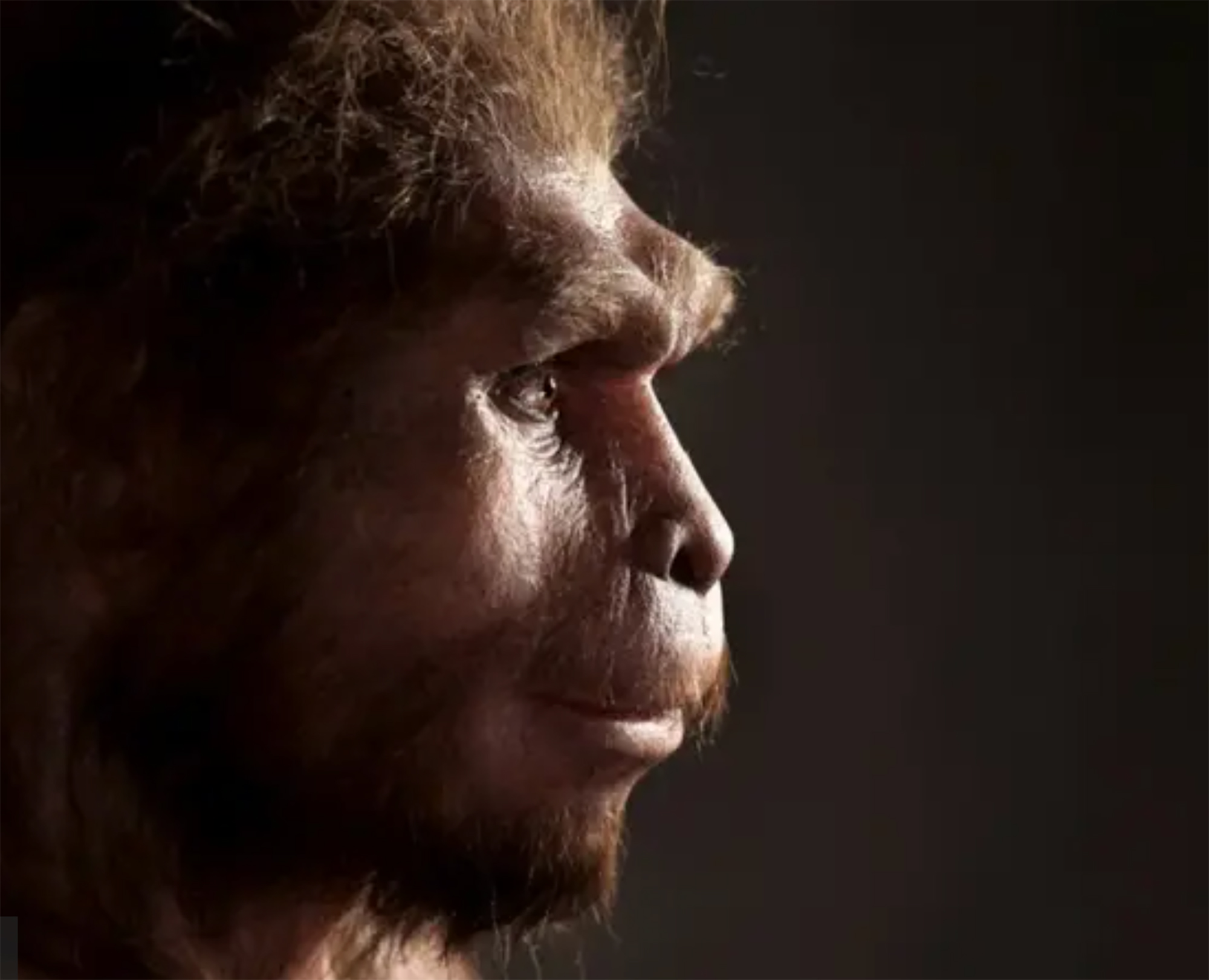

Rudolf Botha hizkuntzalari hegoafrikarrak hipotesi bat bota berri du Homo erectus-i buruz: espezieak ahozko komunikazio moduren bat garatu zuen duela milioi bat urte baino gehiago. Homo sapiens-a da, dakigunez, hitz egiteko gai den espezie bakarra eta, beraz, hortik... [+]

Böblingen, Holy Roman Empire, 12 May 1525. Georg Truchsess von Waldburg overthrew the Württemberg insurgent peasants. Three days later, on 15 May, Philip of Hesse and the Duke of Saxony joined forces to crush the Thuringian rebels in Frankenhausen, killing some 5,000 peasants... [+]

Aramu + AimarZ

When: April 26.

In which: The Zumarraga Open Field.

---------------------------------------------------------

The website of the City Council says: "The tourist brand Viva Viva and the festival of the same name are designed to show the world the soul of... [+]