Society

Environment

Politics

Economy

Culture

Basque language

Feminism

Education

International

Opinion

friday 09 may 2025

Automatically translated from Basque, translation may contain errors. More information here.

The less we read, the greater the value of the heritage we will leave written

- What is left for yesterday. Ana Urkiza. Alberdania, 2011 Paper 20 euros, digital 11.20 euros.

Aphorism brings with it brevity and rigor. Moreover, he would have grace and ingenuity above the likelihood, even if the truth was added by the author. The paradox would be something else. Humberto Eco distinguishes between aphorism and paradox as follows: “Aphorism, therefore, something like a maxim that can be done, right, although it resorts to acuteness, while the paradox relative a maximum false facie, only once a biased reflection, something that the author thought was true. For this reason, its sharpness lies in the hiatus between the provocative way it adopts and what the public expects”. (Therefore, aphorism is an expression that wants to convey a truth, even if it goes to the event. Paradoxically, the prima facie proposition would be false; after a deep reflection, it seems that it explains something that the author considers true. Therefore, its sharpness is based on the hiatus that occurs between the provocative way it takes and that which the public expects).

Urkiza has published in the book aphorisms loaded with sentences that have leaped many of the beliefs rooted in society: “When I head down, I see the world online,” or “Politicians never get it right. Not even when they fulfill the hypothetical pretension of

the majority”. Besides reflecting on what happens in the environment, Urkiza talks about love, perfection, gender and many other issues: “Most of the time the woman has to welcome the man as a penis,” “Start proclaiming that we

are whole oranges,” “Liftina has the power to erase the story, to make up the lie.” But in addition to aphorisms, Urkiza’s work is full of paradoxes: “Who doesn’t have a menstruation doesn’t know what a real stomach ache is; hence the wars that give the headache”, “To learn to be rich, better register before in poverty”, “For money we sell everything, even that which cannot be bought with money”. The aphorisms are not new in our environment and have appeared

without interruption. Xabier Altzibar recently published an interesting article in the journal Euskera: Eskaraz eguia (1858) by Juan Martín de Iribarren, erranas and aphorisms. Between what Hiribarrena said at the time and what Urkiza just launched, there are remarkable differences, but also similarities: the language and the vision and the truth that each gives about his time. Despite

aphorism and aphorism, it is evident that many aphorisms are written and read because they are related to context or are small reading capsules. What happens is that the readers appreciate them, even if it is a pity, because “the less we read, the greater the value of the heritage that we will leave written”.

Urkiza has published in the book aphorisms loaded with sentences that have leaped many of the beliefs rooted in society: “When I head down, I see the world online,” or “Politicians never get it right. Not even when they fulfill the hypothetical pretension of

the majority”. Besides reflecting on what happens in the environment, Urkiza talks about love, perfection, gender and many other issues: “Most of the time the woman has to welcome the man as a penis,” “Start proclaiming that we

are whole oranges,” “Liftina has the power to erase the story, to make up the lie.” But in addition to aphorisms, Urkiza’s work is full of paradoxes: “Who doesn’t have a menstruation doesn’t know what a real stomach ache is; hence the wars that give the headache”, “To learn to be rich, better register before in poverty”, “For money we sell everything, even that which cannot be bought with money”. The aphorisms are not new in our environment and have appeared

without interruption. Xabier Altzibar recently published an interesting article in the journal Euskera: Eskaraz eguia (1858) by Juan Martín de Iribarren, erranas and aphorisms. Between what Hiribarrena said at the time and what Urkiza just launched, there are remarkable differences, but also similarities: the language and the vision and the truth that each gives about his time. Despite

aphorism and aphorism, it is evident that many aphorisms are written and read because they are related to context or are small reading capsules. What happens is that the readers appreciate them, even if it is a pity, because “the less we read, the greater the value of the heritage that we will leave written”.

Most read

Using Matomo

#1

#2

#3

Lurraren Defentsan Euskal Herria Bizirik

#4

Mikel Garcia Idiakez

Newest

2025-05-09

Olaia L. Garaialde

Menopausian elikadura lagun izateko tresnak

Andrea Velasko dietista eta nutrizionistak elikaduraren bidez menopausiak eragindako aldaketak kudeatzeko zenbait gako eman ditu.

2025-05-09

Uxue Gutierrez Lorenzo

Ondo ereindako uzta

BRN + Auzoko eta Sain mendi + Odei + Monsieur le crepe eta Muxker

Zer: Uzta jaia.

Noiz: maiatzaren 2an.

Non: Bilborock aretoan.

---------------------------------------------------------

Ereindako haziek ura, argia eta denbora behar dute ernaltzeko. Naturak berezko ditu... [+]

2025-05-09

Euskalerria irratia

On May 18th they will celebrate the Feast of Creation in Takonera

After a six-year hiatus, on May 18, the Surge party will be held in Takonera to support Model D public schools. There will be shows, games for children and concerts by Gorka Urbizu and/or Borla.

2025-05-09

Idoia Rodriguez Mondragon

It's for your benefit.

Seeing how many psychologists, doctors, therapists... share miraculous methods, one can think that the education of children is an international concern and that we have all become experts.

2025-05-09

Xabier Letona Biteri

47 million euros more was "safe" to guarantee the safety of the Esa reservoir

The President of the Ebro Hydrographic Confederation (CHE) made the announcement at the beginning of the week: The fourth adaptation of the works for the expansion of the Esa reservoir will be launched this year and 47 million euros will be spent to stabilize the right side of... [+]

2025-05-09

Arabako Alea

Vitoria-Gasteiz gardeners meet with the city council for the first time

The City Council of Vitoria-Gasteiz said the company is calling for negotiations. The unions have asked him to defend the workers of Vitoria-Gasteiz against the US investment fund that owns Enner.

2025-05-09

Onintza Irureta Azkune

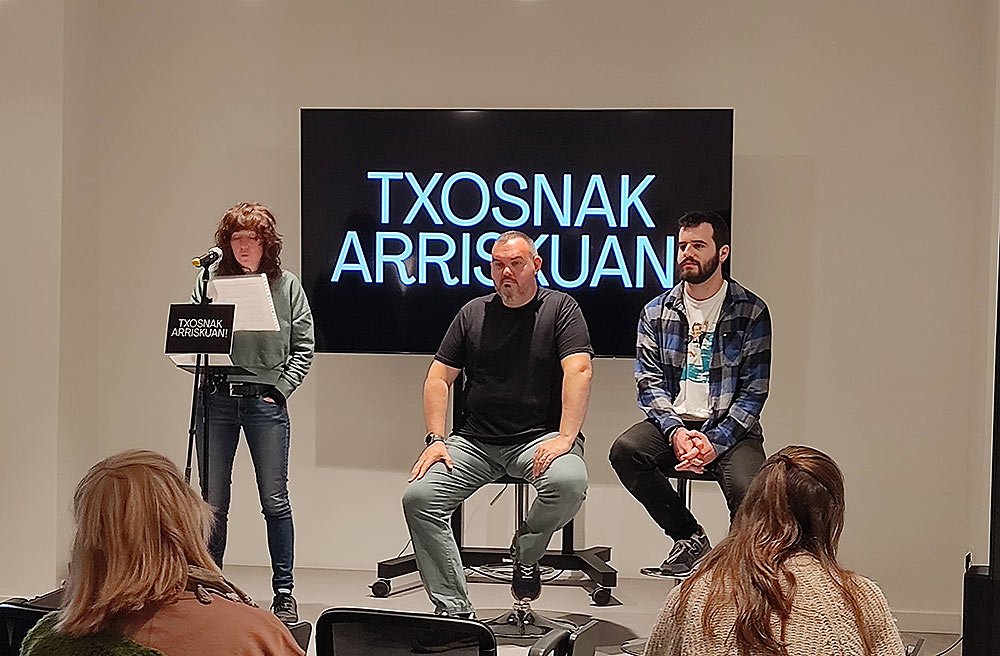

Patxi Saez Beloki Member of ZirHika

“Even doing Hikaz, you learn by doing”

For the first time in the series, there will be a hike. Eighty-three villages have been registered. The initiative is organized by the ZirHika operative group, which was created last year to promote the Hitano, together with Taupa. We interviewed Patxi Saez Beloki, member of... [+]

2025-05-09

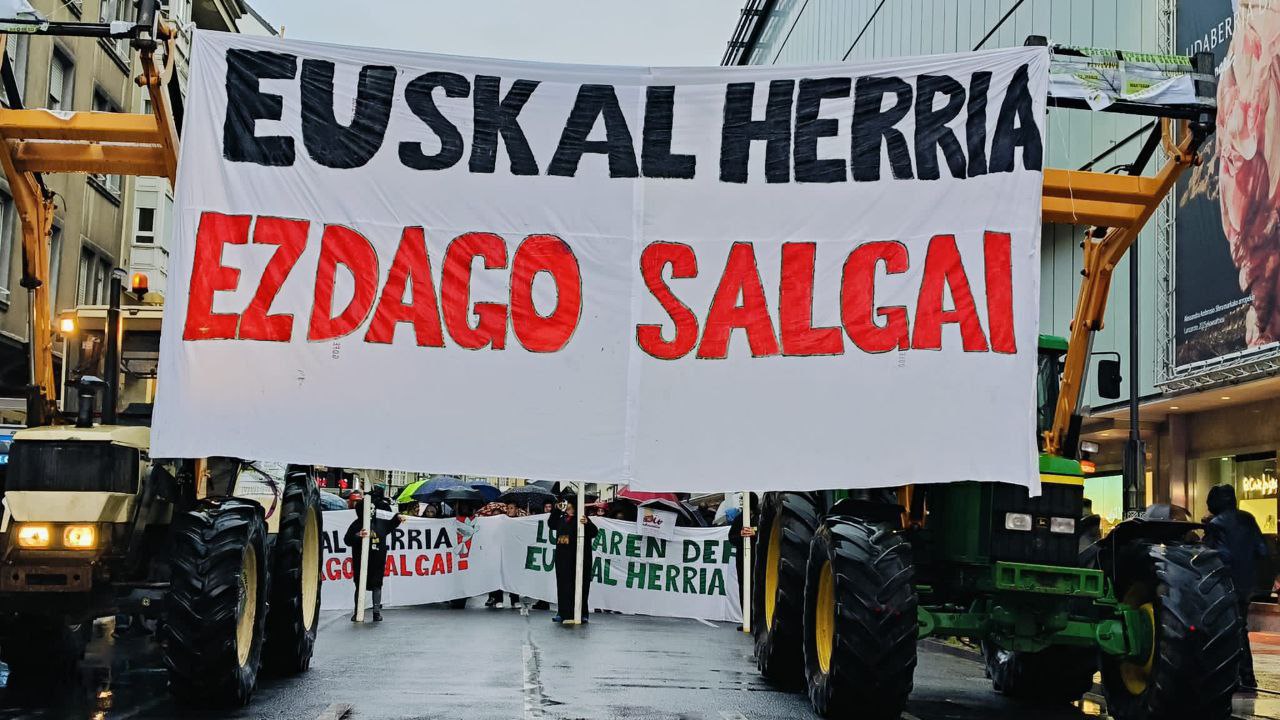

Lurraren Defentsan Euskal Herria Bizirik

The solution is not technical, it is social; the answer to Arnaldo Otegi

In recent weeks, the debate on renewable energies has been spreading in the media. In the Basque Country, we first had the media case of the attack suffered by Aritz Ochandiano, whom he attributed to his support for renewable energies; a few days later, the great blackout, and... [+]

2025-05-09

Urko Apaolaza Avila

Turiel: “Bilatu daitezke arrazoi teknikoak, baina itzalaldia prezioen sistema perbertsoak eragin zuen”

Antonio Turiel fisikari eta CSICeko ikerlariak aspaldiko urteetan ez bezala bete zuen Hernaniko Florida auzoko San Jose Langilearen eliza asteazkenean. Zientoka lagun elkartu ziren Urumeako Mendiak Bizirik taldeak antolatuta Trantsizio energetikoaren mugak izeneko bere hitzaldia... [+]

2025-05-08

Gorka Peñagarikano Goikoetxea

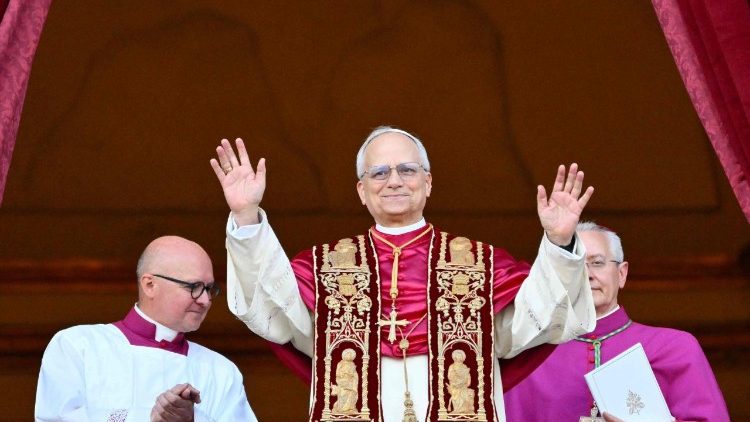

The American Robert Prevost will be the new pope, Leo XIV

He will be the 267th pope of the Catholic Church. The conclave lasted only one day.

2025-05-08

Mikel Garcia Idiakez

Negotiations between public education teachers and the government continue on Friday

2025-05-08

ARGIA

Iratxe Sorzabal has been acquitted by the National Court because self-incrimination was "the result of ill-treatment"

2025-05-08

Unai Lomana Uribezubia

In the interview conducted by the New Sueskun River:

"We have organized a joyful event to proclaim that Basque belongs to all of us"

The Sorioneku movement has called for a mobilization for Saturday. In the morning they will meet from village to village in the bridges of Navarre and in the afternoon they will start a demonstration in Pamplona. It has been revealed that it will not be a "traditional"... [+]

Eguneraketa berriak daude