Which pocket did the money get out of?

- The Franco uprising against the republic was actively financed by several well-known and important families in Bizkaia and several Basque institutions, especially those in Navarra. Former banker José Ángel Sánchez Asiain has been in charge of showcasing the award in the work entitled The Financing of the Spanish Civil War.

In reference to Franco's 1936 Colombian military uprising, the author states: “Without funding in Navarre, March and Portugal, the uprising was not going to go ahead; in a few weeks it would be undone.” This is one of the conclusions drawn by the Basque professor, economist and banker who was president of BBVA after more than twenty years of research. The book, of 1,309 pages, has recently been published by the editorial Critique, under the title The Financing of the Spanish Civil War. The book provides an overview of how the finances and economy of collectors and Republicans materialized. In this extensive work, therefore, we analyze the finances of both parties, the role of the banks and the banks, the collection of Republicans and Francoists, and the financial independence of Catalonia and Euskal Herria.

Sánchez Asiain adds the following subtitle to the work: A historic approach. It says that, in short, it has been nothing more than the transport of materials collected and contrasted for years, and that it has made some reflections, in its own words, that can be personal thoughts, also very personal ones. With these reflections, the author has wanted to delve into what the Spanish Civil War was like from the economic and financial point of view. It emphasizes that this is a historical approach, because it is aware that there are too many questions, too many visions and situations of the same phenomenon ... But, in his opinion, new contributions and information are never too much in history to clarify “what happened”. For the ex-banker, therefore, the results of the studies on the financing of the civil war are not definitive, so he asks that the information be communicated to the people who have it so that they can finish their work.

First-hand documents of the Bank of Spain

The information provided by Sánchez Asiáin has very reliable sources. Half a century ago, Banco de Bilbao began as the head of the Study Service. His director, who was an advisor to the Bank of Spain during the civil war, lent him several documents. According to these documents, the normality of the economy was interrupted between 1936 and 1939: two pesetas, two Spanish banks, two processes of inflation and two ways of understanding society, which were absolutely opposed. For the former banker, it is “by no means a laboratory case”. In the financial world, I was assuming more and more responsibilities, but Sánchez Asiain did not stop studying the issue. Even when he entered the Royal Academy of Spanish History, the introductory lecture was on this topic:Spanish banking in the civil war.

The former banker has had an excellent material at his disposal: recorded interviews with 150 people who were responsible for offices during the war, archives of BBVA – which he chaired for several years –, the Ministry of Economy, the Academy of Moral Sciences and the Foundation of the Spanish University.

How much did the war cost?

The author has not given figures on the costs of the civil war, but does not rule out any future occurrence, as he is still investigating this. In any case, it makes an overall assessment: “The Republic paid the civil war with the savings of the past – gold deposited in the Bank of Spain – and was financed by the government of Franco de Burgos with the future savings – external indebtedness”. As Asiain explained, both parties received voluntary contributions (subscriptions) and non-voluntary contributions (requisitions), as demonstrated by what happened with the Basque Republican Ramon de la Sota.

Special War Tax in Navarra

The Provincial Council of Navarre was serving the “Army and the national liberation movement of the people” and was very important in the financing of the civil war. The Provincial Council of Navarre, for its tax and revenue capacity, was the one that controlled the Provincial Treasury of Navarre. In August 1936, the Council decided to impose a special war tax to cover the expenses of the Franco uprising. Revenue and net revenue generated by capital, whatever its nature, was taxed “on an extraordinary basis” on any form of remuneration, whether in money or in kind – derived from personal work – and on the tax or equivalent capital of commercial companies or associations”. Tax bases were, where appropriate, subject to a certain compulsory quota: 6% for amounts between 3,000 and 6,000 pesetas and 50% for bases above 300,000 pesetas. To generalize the tax, all men of Navarre exempted from the tax had to pay a fixed fee of 100 pesetas per year, except those who, aged between 18 and 28, were registered as volunteers in the Army or in some militia.

Between January 1937 and March 1938, the extraordinary war tax collected 12.5 million pesetas. The Member of Navarre also introduced other war taxes: spectacle taxes, tobacco and tax for the granting of subsidies and war care. With these “war taxes” he raised 13,942,813,12 pesetas between 1937 and 1941. In order to understand the effort made by Navarre in favour of the Franco uprising, it is sufficient to point out that the total amount of taxes provided for in the budgets for the year 1936 in Navarre amounted to 18,903,519 pesetas and that most of Navarre’s expenses were allocated to the direct contribution to the State, in accordance with the 1927 agreement, for the amount of six million pesetas.

The Deputy granted loans to military General Mola, the military head of the city and one of the keys to the uprising to support the uprising and “protect religion, peace material and our foreign freedoms”, in addition to creating economic aid to the families of the volunteers and making subscriptions among the citizens to the soldiers of the province.

Weapons, constant concern of Carlists

The contribution of the Carlists – Navarra was one of its pillars – was fundamental for the development of the Colombian uprising. According to Sánchez Asiáin, one of the main concerns of the Carlists was how the weapons were acquired, bought and taken to the hidden hiding places of Euskal Herria, or if they were not transported to Portugal. In June 1936, Carlists bought a lot of war material abroad with the money Mussolini had lent them. Javier de Borbón and Fal Conde were in charge of this. The Zugarramurdi, Bertiz and Aezkoa and Pasaia Mountains were the main steps towards the transport of arms, and were subsequently transferred to Berbinzana, Corella and Cascantera. In addition to acquiring the weapons, the carlists also made them. Among other things, they carried out hand pumps in the small factories of Caparroso and Mañeru. And in Traibuenas, they had created a large stockpile of weapons.

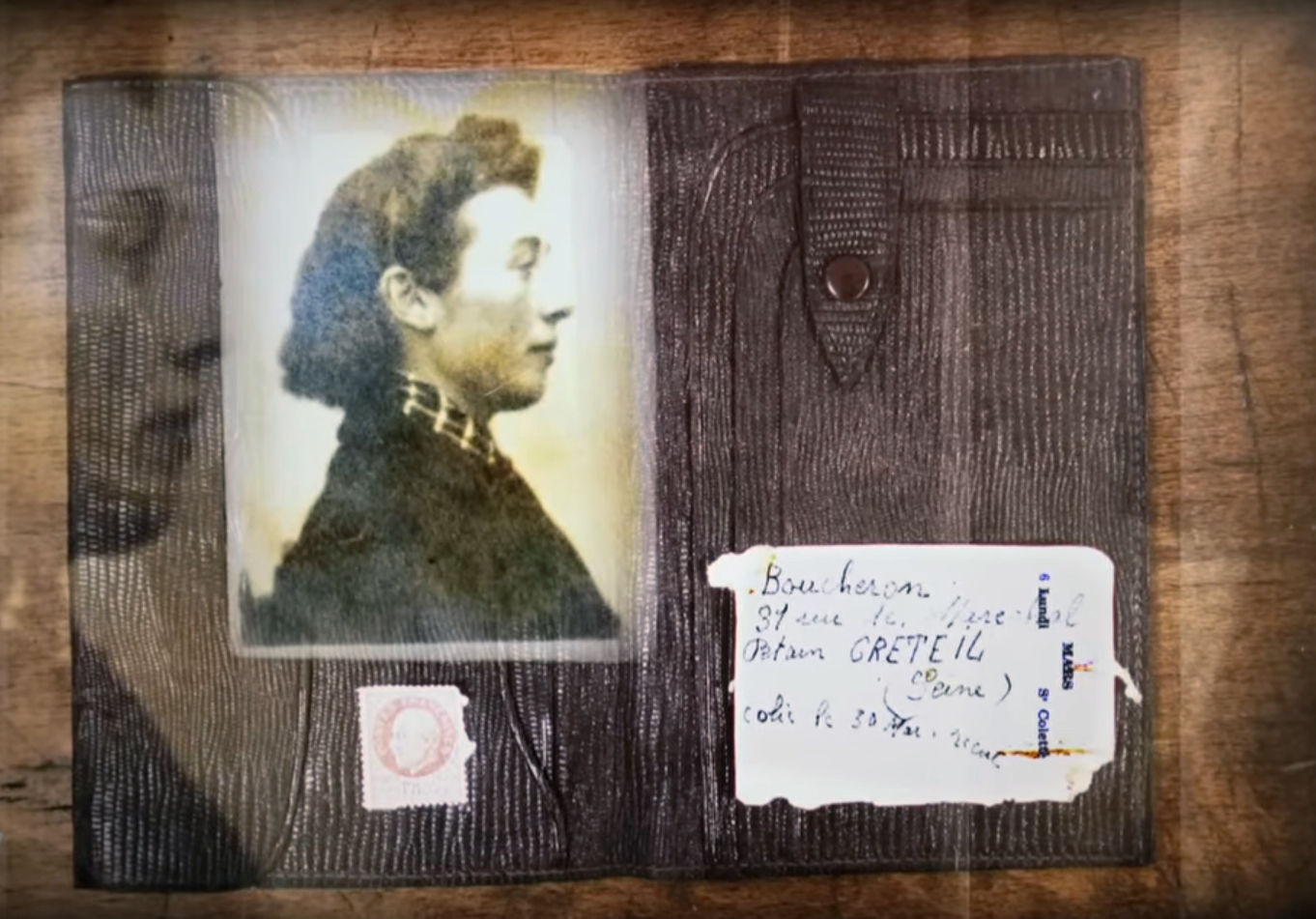

The Marqués de Arriluce de Ybarra, collector

According to a study carried out by Asiain at the end of September 1932, financial resources had already been raised to combat the republic. A commission was set up to raise money. Abroad, the commission was chaired by the Count of the Andes and in the Spanish state by the Marqués de Arriluce de Ybarra. The list of “Tax Contributors” lists the Basque families known: José Luis de Oriol (1 million pesetas); Juan Tomás Gandarias (250,000 pesetas). ); Marqués de Urkijo (250,000); Widow of Zabalburu (250,000 pies. ). ); Garay (250,000); the widow of Zubiria, countess (200,000); the count of Aresti (200,000); the widow of Txabarri (200,000); the marquis of Txabarri (200,000); the marquis of Triano (100,000); Agirre (300,000); the marquis of Arriluce de Ybarra (500,000). Inevitably or willingly, millions of pesetas left the pockets of the rich in the Basque Country to help Franco.

Altxamendu frankistak, edonola ere, ez zuen dirua Nafarroatik, March etxekoen eskutik eta atzerritik soilik bildu. Jurisdikzio berezi bat ere baliatu zuten, erantzukizun politikoena, hain zuzen, 1939ko apiriletik aurrera ere luzatu zena. Kasu paradigmatikoa da Ramon de la Sotaren familiarena. Errepublikarekiko leial, Euskal Herriko aberastasun handienetakoa zuen.

Ramon de la Sota 1938an hil bazen ere, haren eta haren familiaren aurkako espedienteek irekita jarraitu zuten. 1938ko urtarrilean, Ramon de la Sotari –ordurako, hila– eta haren semeei isun ekonomikoak ezarri zizkieten. Aitari 100 milioi pezetako isuna ezarri zioten; hiru semeei, berriz, 100, 80 eta 60 milioikoak. Ilobetako bati 20 milioikoa ezarri zioten. Haiez gain, zigortu egin zituzten Sotaren alarguna, alabak, errainak eta suhietako batzuk. Guztira, 13 pertsona. “Zenbatekoei dagokienez, agintari frankistek Espainia guztian ezarritako isunik handienak izan ziren”, dio Sanchez Asiainek. Eta horrez gain, dio isun horiek irmoak zirela, eta ez zegoela haien aurka errekurtsoa jartzerik. Akusatuek 15 egun zituzten isunak ordaintzeko. Bestela, haien ondasun guztiak Estatuarentzat izango ziren. Sotatarrei, ordea, ez zieten ebazpena pertsonalki jakinarazi, hilda edo ihes eginda baitzeuden, eta ebazpena ez zen argitaratu ez Espainiako Boletin Ofizialean ez Bizkaiko Aldizkari Ofizialean ere.

1935ko abenduaren 31ko balantzearen arabera, Ramon de la Sota Taldearen ondasun higiezinek 35,3 milioi pezetako balioa zuten. Eraikinei dagokienez, besteak beste honako hauek konfiskatu zizkioten: Ibaiganeko jauregia, gero Bizkaiko Gobernu Militar bihurtua eta egun Athleticen egoitza dena, eta beste eraikin batzuk, Bilboko Mazarredon eta Kale Nagusian. Enpresak 4,7 milioi pezetako balore zorroa zuen, eta gainera, 1,2 milioi zituen taldeak kreditutan. Guztira, 41,2 milioi pezeta. Taldearen funts propioak 10,7 milioi pezetakoak ziren. Bestalde, De la Sotak partaidetzak zituen Bizkaiko 447 sozietate anonimotan. Hau da, aberastasun izugarria zuen familiak, orduko milioi pezetak oraingo milioi euroekin konparatzen dakienak ikus dezakeenez.

Bilbon ireki zioten Ramon de la Sotari espedientea, 1937ko ekainaren 19an, hiria Mola jeneralaren eskuetan erori eta egun gutxira. Eta 1966an indultua eman zitzaien arte iraun zuen. Ramon de la Sota semea eta haren anaiak, Alejandro eta Manuel, prozesatu egin zituzten. Behin-behineko askatasuna eman zieten, baina enpresa kontseiluetako eta gerentziako karguetan egotea debekatu zitzaien. 1982an, berriz, ezarritako isuna gauzatzeko Estatuak 1940ko hamarkadan bereganatutako ondasun guztiak berreskuratu ahal izan zituzten, Konstituzio Auzitegiaren epai baten ondorioz.

Kirola eta oroimena uztartuko dituzte, bigarrenez, mendi-martxa baten bitartez. Ez da lehiakorra izanen, helburua beste bat delako. La Fuga izeneko mendi martxak 1938ko sarraskia gogorarazi nahi du. Ezkabako gotorlekuan hasi eta Urepelen amaituko da. Maiatzaren 17an eginen dute.

Fusilamenduak, elektrodoak eta poltsa, hobi komunak, kolpismoa, jazarpena, drogak, Galindo, umiliazioak, gerra zikina, Intxaurrondo, narkotrafikoa, estoldak, hizkuntza inposaketa, Altsasu, inpunitatea… Guardia Zibilaren lorratza iluna da Euskal Herrian, baita Espainiako... [+]

Gogora Institutuak 1936ko Gerrako biktimen inguruan egindako txostenean "erreketeak, falangistak, Kondor Legioko hegazkinlari alemaniar naziak eta faxista italiarrak" ageri direla salatu du Intxorta 1937 elkarteak, eta izen horiek kentzeko eskatu du. Maria Jesus San Jose... [+]

Familiak eskatu bezala, aurten Angel oroitzeko ekitaldia lore-eskaintza txiki bat izan da, Martin Azpilikueta kalean oroitarazten duen plakaren ondoan. 21 urte geroago, Angel jada biktima-estatus ofizialarekin gogoratzen dute.

Bilbo Hari Gorria dinamikarekin ekarriko ditu gurera azken 150 urteetako Bilboko efemerideak Etxebarrieta Memoria Elkarteak. Iker Egiraun kideak xehetasunak eskaini dizkigu.

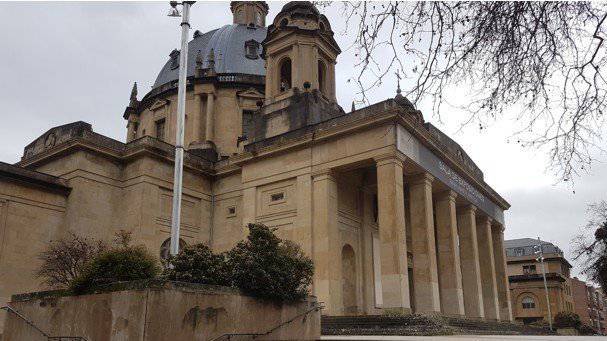

33/2013 Foru Legeari Xedapen gehigarri bat gehitu zaio datozen aldaketak gauzatu ahal izateko, eta horren bidez ahalbidetzen da “erregimen frankistaren garaipenaren gorespenezkoak gertatzen diren zati sinbolikoak erretiratzea eta kupularen barnealdeko margolanak... [+]

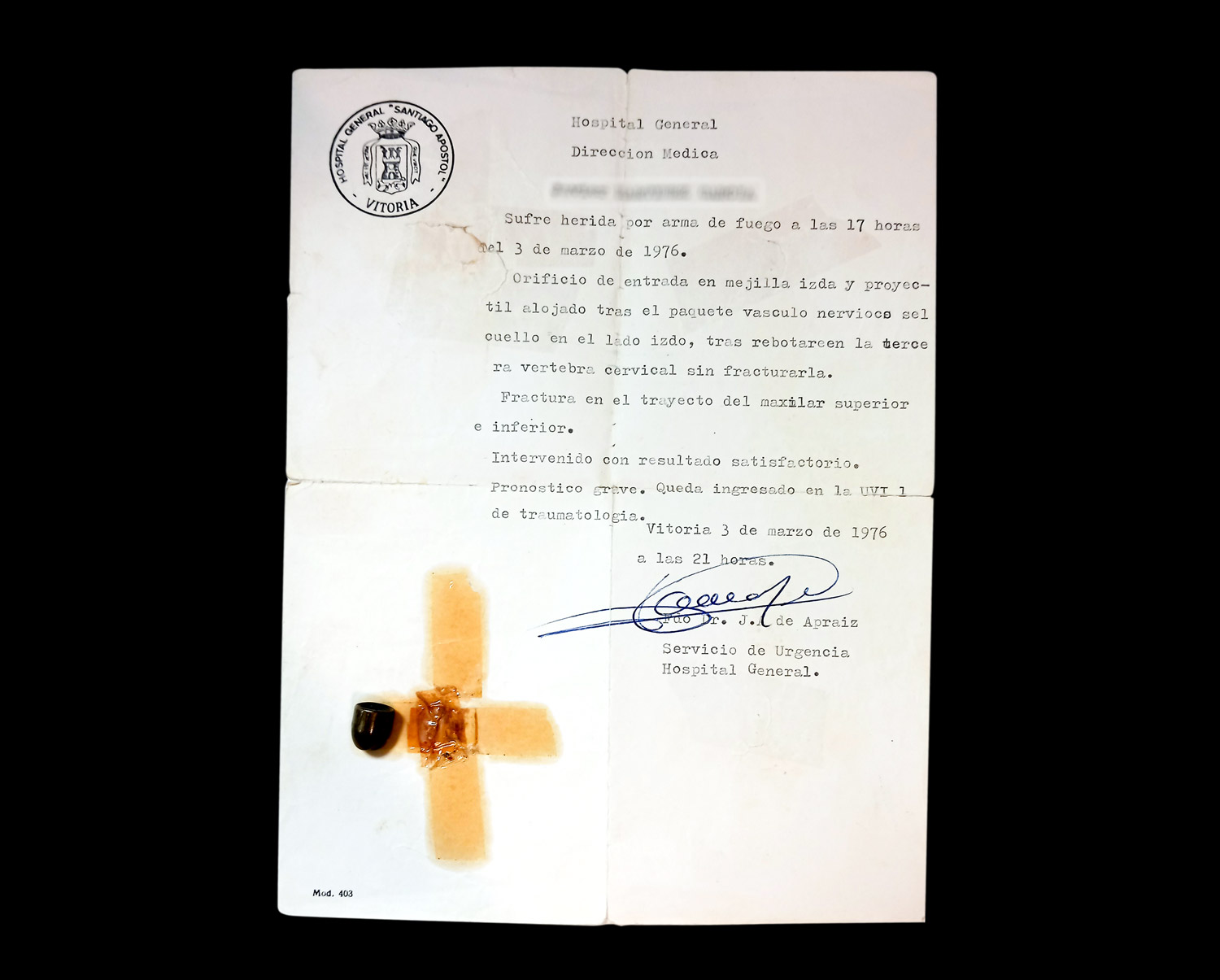

1976ko martxoaren 3an, Gasteizen, Poliziak ehunka tiro egin zituen asanbladan bildutako jendetzaren aurka, zabalduz eta erradikalizatuz zihoan greba mugimendua odoletan ito nahian. Bost langile hil zituzten, baina “egun hartan hildakoak gehiago ez izatea ia miraria... [+]

Memoria eta Bizikidetzako, Kanpo Ekintzako eta Euskarako Departamentuko Memoriaren Nafarroako Institutuak "Maistrak eta maisu errepresaliatuak Nafarroan (1936-1976)" hezkuntza-webgunea aurkeztu du.