Like sheep without a shepherd?

- After the conquest of the kingdom by Castile, there was a great debate about the participation of the Courts in the political life of Navarra. There were those who argued that the Courts should be superior to the king, and for this they resorted to the past: the kingdom was ruled without king in search of the interregnum.

The myth that Castile respected the institutions and laws of the kingdom of Navarre after the conquest has been widely recognized by some historians. While recognizing that the process of conquest was hard, many Navarrist historians have brought out the so-called status that Navarre had later to defend that the fact that he was ultimately forced to join Spain was beneficial.

But the story is more complex. In fact, the status of Navarre was the subject of debate in the sixteenth, seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, and in the conflicts and debates that took place throughout this time it is not difficult to see that in Navarre and Castile there were very different views regarding the situation of the new kingdom conquered. And it doesn't take long to wait, because the conquest ended and few Navarros writers began to renew historiography with the intention of ending the new situation. In fact, as historian Fernando Mikelarena has recently claimed, life began in 1521.

They ruled so well that they didn't need the king.

The Prince of Viana prepared his Chronicle in the years 1453 to 1455, being Navarre independent. The prince had only one purpose to have this text written: he wanted to assert his right to become king in the presence of John II.aren. In the account of the chronicle, therefore, everything is a tribute to the legitimate kings and a rejection of the usurpers. The king, in the conception of the Prince of Viana, is the key piece in the political architecture of Navarra. As to what it was like at the beginning of the kingdom, the Prince notes that the Navarros were for some time without king, after the death of the king without heirs: in spite of all the efforts, the Navarros were “like sheep without shepherd” at that time.

This concept changed significantly in the first years of the conquest. In the Chronicle written around 1534, historian Diego Ramírez Avalos of the Pool, like the Prince of Viana, tells us an interregnum. But on this occasion, before his death, the king summoned the upper lords of the kingdom and gave the order to rule the kingdom to twelve nobles. And so, says Ávalos, those twelve nobles “ruled so well that they did not need the king.” Moreover, his authority was so great that “according to the law and the law, they have so far had a priority over the king and his counsel.”

Ávalos de la Piscina was not studying antiques without interest. He referred directly to the new situation in Navarre: the twelve nobles in the text were the Courts of the 16th century that were on the king and the Royal Council that defended his power. In other words, the king could not legislate without the opinion of the Courts – as he did in Castile –: he had to listen to the voice of the Courts. Here's the message from Ávalos. In his Chronicle, the Navarros had gone from being sheep without a shepherd to not needing the king: Avalos of the Pool tried to reinvent the present with a new look at the past.

Because there are no laws without kingdom, no kingdom without laws ...

Thus, with this phrase, the Courts asked him to accept the reduced Fuero, in 1530. This reduced jurisdiction – The reduced jurisdiction could be the appropriate translation – although the recovery project was prior to the conquest, it materialized after the conquest. In it was updated the Medieval General Fuero, “without adding anything new”, or so pointed out the Cortes.El

Fuero une danced in the 16th century, but neither Carlos I.ak nor Felipe I I.ak, who so loved and respected the Navarre institutions, wished to consent ever. If you want them to use it, but better not give their consent, it was the council of the Council of Castile.

And actually, even if the Courts say otherwise, there were new things in the Common Jurisdiction. For example, this rarity. The entrance to the Medieval General Court said: “In principle, the Fuero established the choice of the king in Spain...”, while in the proposed Unified Jurisdiction the following phrase was written: “In the beginning, the Fuero established the choice of the king in Navarre...” Also in the Unified Jurisdiction the past was being rewritten to better confront the present.

From the Ordinances to the Laws of the Trustees

In any case, from Castile they also tried to rewrite the historiography and history of Navarra from the point of view that would suit them. After ruling out the unified jurisdiction, but seeing that the laws were necessary, the Council of Kings pushed for its collection of laws. The result was a book entitled Ancient Ordinances, written by lawyers Pedro Balance and Pedro Pasquier and published in 1557. It presents all kinds of laws, some dictated by the king and others agreed by the king with the Courts. But not all of them are identical. Those established by the King are listed in the first book, while in the second there are those who had the participation of the Courts. The text of the former is literally copied, while the text of the latter is summarized. These are the evidences that almost involuntarily establish a small hierarchy between the two kinds of laws.

For his part, Pasquier attributes to the king all the merit of the legal illustration of the kingdom. Since ancient times, the Navarros have been skilled in fighting the Moors, would write Pasquier in 1567, but have not been curious to collect and print their laws, the outlaws and the ordinances. The consequence was clear: By the order of the king and by the work of Pasquier, that savage and lawless time had come to an end. The conquest, in short, brought the illustration to Navarra.

The Courts never accepted the collection of Balance and Pasquier laws, although in practice they used it, but until the seventeenth century they were unable to publish the collection they considered appropriate. Two “officials” of the Courts, Pedro de Sada and Miguel de Murillo, prepared it in 1614. This collection did not contain any laws without the participation of the Courts and, from the front line of the entrance, Sada and Murillo guided the historical interpretation of Pasquier: “In Navarre, the responsibility for making good governance laws has always been as old as choosing kings to manage them well.”

Endless and endless debate

In the beginning of the sixteenth century, after the conquest, a wide space was extended under the concept of “integration”, which became a space of struggle. It is not true that Castile respected or promoted the Navarre institutions. The tolerance observed by the monarchy to maintain peace does not mean that the relationship between the conqueror and the conquered was good or not conflictive.

As soon as the conquest occurs, the signs we find everywhere show that in Navarre a process of review and rewriting history had begun so that the kingdom would continue as independent as possible, or as autonomous as possible. But this writing with the new eyes of history took place in a polemical way, fighting with the versions that came from Castile and, in some cases, from Aragon. We've quoted here the Avalos Chronicle of the Pool, but historiography really flourished in the 17th century, in an endless conversation with legends from the outside. We've mentioned the unified rage and the collections of laws, but the king refused to approve the first, and the attacks on the exiles happened over and over again.

The happy integration of Navarre was fiction, but in part the fiction invented by the Navarros themselves to respond to fictions that were not so beneficial to the kingdom. Forgetting the (intentional) perspective of that time, the use made by the Navarrists of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries is another aspect to be counted at another time.

“Even with all the shortcomings, the unions have done more for humanity than any other human organization that has ever existed. They have contributed more to dignity, honesty, education, collective well-being and human development than any other association of people.” ... [+]

Harri-jasotzearen gorakada nabaritu da azken urteetan, batez ere emakumeen artean. Gazteek harri eskoletan ikasten dute kirolean esperientzia dutenengandik. Crossfit-a, sare sozialak eta telebista faktore garrantzitsuak izan dira kirolaren piztualdian, harri eskolekin batera... [+]

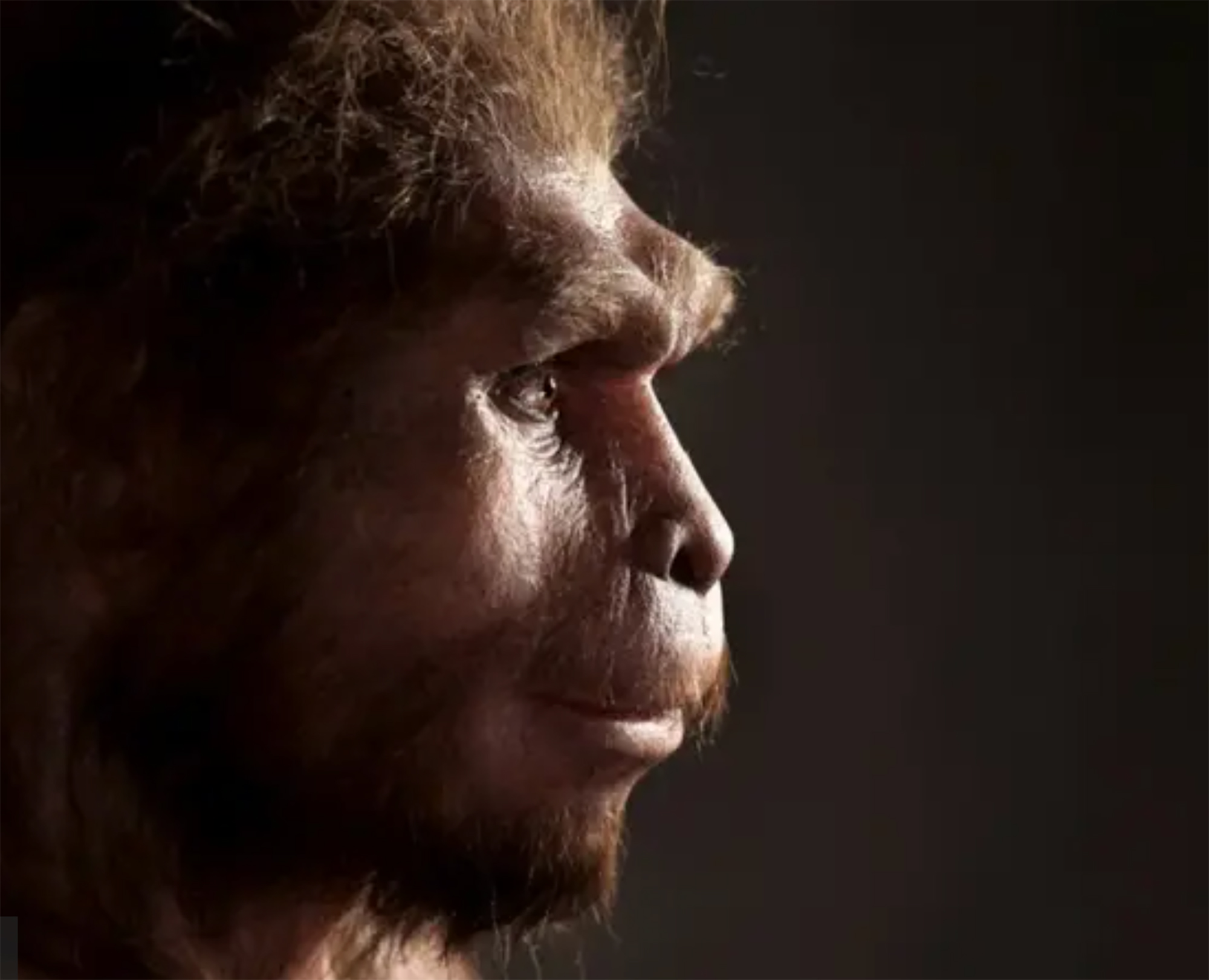

Rudolf Botha hizkuntzalari hegoafrikarrak hipotesi bat bota berri du Homo erectus-i buruz: espezieak ahozko komunikazio moduren bat garatu zuen duela milioi bat urte baino gehiago. Homo sapiens-a da, dakigunez, hitz egiteko gai den espezie bakarra eta, beraz, hortik... [+]

Böblingen, Holy Roman Empire, 12 May 1525. Georg Truchsess von Waldburg overthrew the Württemberg insurgent peasants. Three days later, on 15 May, Philip of Hesse and the Duke of Saxony joined forces to crush the Thuringian rebels in Frankenhausen, killing some 5,000 peasants... [+]

Aramu + AimarZ

When: April 26.

In which: The Zumarraga Open Field.

---------------------------------------------------------

The website of the City Council says: "The tourist brand Viva Viva and the festival of the same name are designed to show the world the soul of... [+]

Zenbait urtetatik hona sarri entzuten dugun kontzeptua da zaurgarritasuna. Gaur gaurkoz, diskurtso politikoetan pertsona zaurgarriez aritzea ohikoa da. Seguru nago nik ere inoiz erabili dudala berba hori Bizilan.eus webgunean, eskubide laboralak eta prestazio sozialak azaltzeko... [+]