"It's time to be alert."

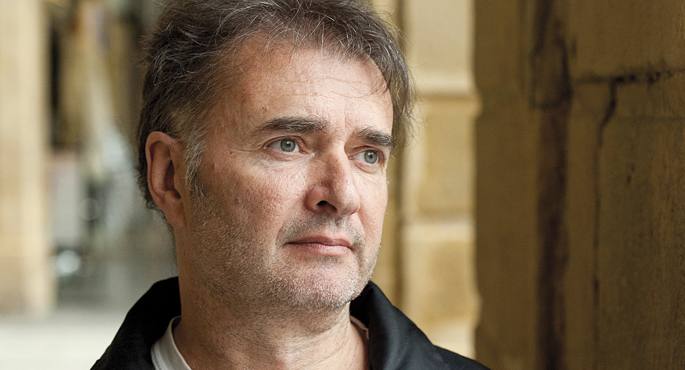

- (Madrid, 1958) An opulent and unusual writer. Great reader, passionate about storytelling and the novel. If so, he has moved away from fiction and has written two essays in recent years: Presence of things and extinction of Civism (Elkar). Consecutive and complementary.

When you presented the presence of things, you mentioned the astonishment of a person who came out in the street after fifteen years in prison: “What people have,” he said, astonished. It's been five years since then...

In the book I state that consumption has meant an increase in things, because we are in the production system, and that does not stop. In recent years we have been in an untenable situation – let us avoid talking about crises – there has been a deficit of money, and many people have come to understand that there are borders. There's also that surprise. However, he who has been in prison for 20 years will be surprised by what he sees, of course. In fact, in the last five years, there's no news like the computer or the cell phone, no news of size, but people are waiting for the next surprise. Nanotechnology is there, and it's suspected that there will soon be something new. I wonder if there is less and less capacity for awe. In other words, we have fallen into the routine, it is the normal use of the telephone and the computer – the disturbing upheavals – as far as we could not imagine. We've been used to changing things, and I would say that we've gotten used to evil, that it creates a lot of problems for us, but in part it's because we want it. Or maybe we use things because we have not been able to deal with them and have had to “accept” all the complications they bring.

The book is not a testimony to “disasters”, however, at this time when “catastrophe” has come, it is even more suggestive, exciting.

As I wrote that, I realized that we were coming to a cairn. That's often been in history, and I don't mean the millennium milennial milestone. I would say that since the 18th century we have reached the brink of progress and material development. There is no longer an upward path, there is talk of growth or lack of growth.

Disaster has many faces: capitalism is one, but not the only one. It also criticizes progress.

It has many faces, some of which are not so catastrophic. It has always been (go) those who live “well”. There are reasons to believe in progress. However, many people have returned to the situation of 50-60 years ago: they have had to accumulate at home, poor working conditions and safety losses have increased. An ELA member said in one of the days of strike that “the crisis has been invented by the capitalist system to make reforms.” I agree. But there are many forms of crisis. We have known the crises of real socialism and capitalism, but the ownership of the state or the private has not been in the hands of the people. The crisis of the socialist experience is the crisis of the productive system, but also the human crisis.

Ivan Illich likes thought. Illich condemned the values transmitted by the school and questioned the knowledge given to it.

Ivan Illich criticized the education system, the healthcare system, the care system and many other things. For me, these criticisms remain a reference. Otherwise, we can continue to talk about capitalism, socialism, monarchy or republic, and there are more basic things. Education, for example, whatever the political system, has become the hands of the State. There are categories, and Cuba, for example, with its socialism, free education and commitment, has become a “champion” of the third world. But like here, the school is not within the reach of people. That is what Illich criticizes most. It not only looks at how we can improve education from within, it doesn't propose an alternative school, it talks about the school alternatives.

Are we in the last tranche of our civilization?

I don't like to make those kinds of predictions. If we talk to young people about that, we seem to be talking about old things. However, 40 years ago we knew the way of life of the dwelling. We can say that we have known some of the remains of peasant civilisation in Europe, and almost together, in addition to removing those last footprints, I would say that they could still look for them. A number of young people are now heading towards the mountain. The symptom may be that some young people will return to small towns, and also that they will have to abandon their past life. I mean, these changes are very important to see what we can do since the life of the first age. It's time to be vigilant.

Your lifestyle makes you appear in the book. We usually say in this world: “We can’t do anything.” You propose “not to do” or “at least not to collaborate”.

I mean things lived from within. In the book – in the books – I mean what people say, what I have known, the consequences I have experienced. It's an attitude. It could be quite radical, apart from commenting on things, I've looked at the mechanism that we get in and into. I have explained whether we are aware of the tools we are using and the steps we take. For example, it's now fashionable to be aware of what we eat. OK. It seems that people have understood it well and in some uses we have developed a critical point. If it is a conclusion that we should not use this or that, then let us be consistent. Or also: there's a lot of people angry with their phones, we've been fooled. Well, if we don't want the cell phone, let's use the cockpit. If the cabin was used by a lot of people, maybe now otherwise, if the cabins were everywhere, well-kept, maybe you wouldn't need the cell phone. Of course, whenever we care not to grow. However, most people are not on that path.

Now we are talking about the extinction of the human race. When I fixed the interview [we stayed at 8:30 in the morning] I told him on the phone “quiet, I am early”. Others are “gauutxori”. Today, perhaps this duality has been extinguished in men.

Do you ask me what our pace is? In itself, the rhythm of nature. And the current pace has been breaking with that. But it's not something new. The natural rhythm changed at least since there was a clock and we worked according to it. I came to the North about forty years ago, and there, unlike Spain, people were already forced to change the hours during summer and winter. But in Urepel’s kitchen the clock always looked the same time: the house did not change, lived “with all the sun”. Who lives like this now? It is therefore apparent that we have become accustomed to evil. There have been protests, those time changes have created discomforts and mismatches, especially in children and the elderly, and also in anyone. Is there any specific reason? In the end, you think to disrupt people. But we accept them. The former baserritars had at least attitudes or symptoms of disobedience.

Feelings, spaces, men and women and children are more visible in this book. I mean, next to things, there are people.

In the exhaustion of the human genus there is a path. Just as in the previous book I introduced many things from my life, here, in this outline of my life, there is a milestone, the year I was born. In the book there are two photographs of 1950-60. Peter is the person I refer to. The one who came to live from Extremadura to Andoain is of the same age. I've wanted to express people's tiredness, how I see people who have run out, the symptoms that look like in that habit of evil. In one photo there are the Gypsies and in the other the peasants, all of them from that time. I met them as a child, in the vicinity of Madrid. I went around and saw people like that, not very good. In other words, we have known the last traces of peasant civilization and it is good that we should not stop losing them...

You've also put the poem Kutxa.

My literature is getting smaller and smaller, and I've had more and more trouble getting words out of it, words are leaving me for the essay, and that poem is proof of it. My intention was to make a book with that idea. I tried to write a book, and I almost got it. I wrote 100 pages, but I diminished and diminished, and I got to that text. My books are becoming more and more limited, I'm not able to make a great novel.

Andoain has been one of the places on your route.

When I was young I went to Lapurdi, since then I made dozens of changes, the longest life I did in Andoain. Thus, these two books, as in previous books, show directly and indirectly the great affection I have for this people and the brand they have left.

Here is a passage from the Patients section: “We launch into a world where such a world is possible or not possible, where pain, pain, has no place.”

I gave the book another name that was left in the subtitle. The feelings of men and women in the third industrial revolution (2009). I've talked about feelings, the readings I've made have led me to the search for feelings. I've compared what men and women today feel to the first thing. One of the things I've found is pain. The question is how we face or escape pain. I am also referring to body pain. There's a lot behind it, a philosophy against effort, a rejection of effort. That things are not easily achieved, that you have to work the land to give something. And I am not for pain, let alone in the Christian sense, that is, you have to suffer in life, because we have come to suffer. However, everyone has to know what has come to the world. Knowing that we can give up something and reject it. Some doctors say that “in today’s world you don’t have to suffer pain.” Listen, everyone will be able to see whether they want that or not. In a word, no apprehensions.

Gora Aiaraldeko Jai Euskaldunak dinamika jarri du martxan aurten ere Aiaraldeko Euskalgintzaren Kontseiluak, Udal eta elkarteekin elkarlanean. Jaien testuinguruan euskararen presentzia eta erabilera sustatzea dute helburu. Iaz abiatutako bidetik jarraitu nahi dute aurten ere,... [+]

Antton Kurutxarri, Euskararen Erakunde Publikoko presidente ordearen hitzetan, Jean Marc Huart Bordeleko Akademiako errektore berriak euskararen gaia "ondo menderatzen du"

88 urterekin hil da Frantzisko aita santua astelehen goizean, iktus baten ondorioz. Azken boladan osasun arazoak izan zituen. Miñan liburua gomendatu zuen publikoki, migratzaileen egoera kontatzen delako.

Hamabost langile humanitario hil zituen Israelgo armadak martxoaren 23an, terroristak zirela eta ez zutela euren burua identifikatu argudiatuta. Bideo batek bertsio hori gezurtatu ostean, gertatutakoaren barne-txostena egin dute Israelgo Defentsa Indarrek, baina bertan esaten... [+]

You may not know who Donald Berwick is, or why I mention him in the title of the article. The same is true, it is evident, for most of those who are participating in the current Health Pact. They don’t know what Berwick’s Triple Objective is, much less the Quadruple... [+]

The article La motosierra puede ser tentadora, written in recent days by the lawyer Larraitz Ugarte, has played an important role in a wide sector. It puts on the table some common situations within the public administration, including inefficiency, lack of responsibility and... [+]

Is it important to use a language correctly? To what extent is it so necessary to master grammar or to have a broad vocabulary? I’ve always heard the importance of language, but after thinking about it, I came to a conclusion. Thinking often involves this; reaching some... [+]

The other day I went to a place I hadn’t visited in a long time and I liked it so much. While I was there, I felt at ease and thought: this is my favorite place. Amulet, amulet, amulet; the word turns and turns on the way home. Curiosity led me to look for it in Elhuyar and it... [+]

Adolescents and young people, throughout their academic career, will receive guidance on everything and the profession for studies that will help them more than once. They should be offered guidance, as they are often full of doubts whenever they need to make important... [+]

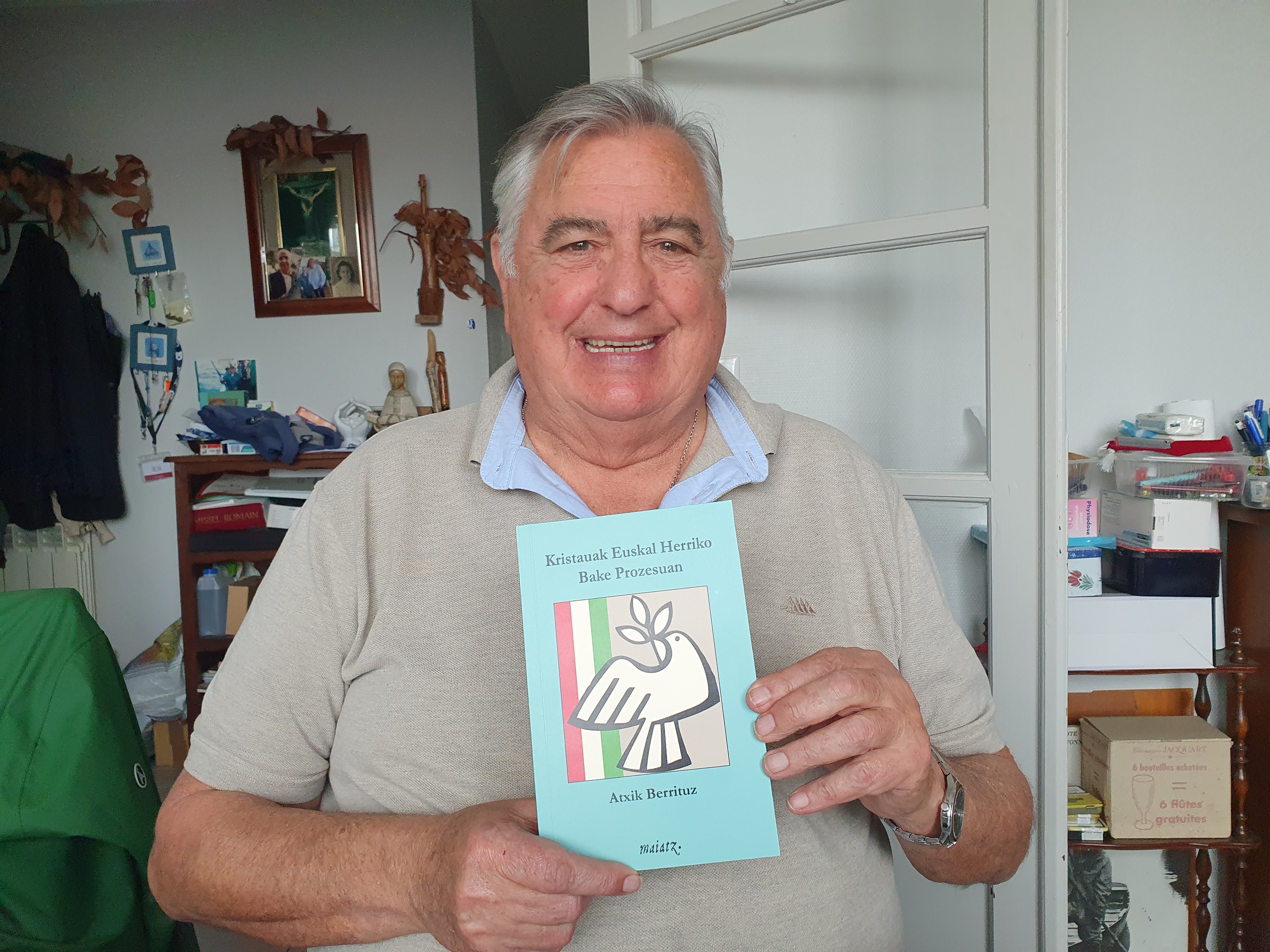

Atxik Berrituz giristino taldeak Kristauak Euskal Herriko bake prozesuan liburua argitaratu du Maiatz argitaletxearekin. Giristinoek euskal bake prozesuan zer nolako engaiamendua ukan duten irakur daiteke, lekukotasunen bidez.