Green economies -- green only the name

- The United Nations Conference on Sustainable Development, better known as Rio+20, will be held from 20 to 22 June in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, at which the Earth Summit was held in 1992. The focus of the summit will be the so-called green economy, which “generates low carbon emissions and uses resources effectively”, according to the UN. Critical voices, particularly ecologists, consider that the green economy is nothing more than a mere layer of varnish, as it does not question the logic of growth.

In 1983, aware of the ecological crisis on the planet, the United Nations General Assembly decided to set up a commission to diagnose environmental problems and recommend the measures to be taken accordingly. The Commission, appointed as the World Commission for the Development of the Environment, issued its report in 1987, under the title of Our Common Future, although better known, in honour of its general coordinator, such as the Brundtland Report.

This report was the centrepiece of the Rio de Janeiro Earth Summit in 1992. He described with great precision the environmental problems, but “he was not able to give an adequate response to the origin of these problems”, according to the Venezuelan researcher at the Transnational Institute, Edgardo Lander. According to Lander's analysis, the Brundtland Report did not take into account any solution to the continued growth of the capitalist model. The road to destruction and environmental poverty was more growth. This would be possible because the advancement of technology would make it possible to produce more and more with fewer resources. This is how the concept of “sustainable development” was born, formalized after the 1992 summit.

It will be done with similar parameters, but with the planet in a more serious situation than twenty years ago. The reason is not only that nothing good could be expected from the false starting point of the Brundtland report. Moreover, most of the measures agreed at that time, including Rio 1992, the germ of the Kyoto Protocol, have not been implemented, or at least not in their entirety. Iñaki Barcena, Nerea González and Rosa Lago, members of Ekologistak Martxan, have stated that "the UN does not have enough power to force governments". It will be three in Rio+20.

The new fetish concept that is going to leave us with this summit will be the ‘green economy’, we do not know – or at least the subscriber does not know – whether it is a substitute or complementary to sustainable development, but in the same vein as it is. Bárcena, González and Lago will not travel to Rio to applaud the authorities that congregate there.

What is the green economy?

The 2011 UN World Economic and Social Report acknowledges that the business routine cannot be continued until now. But he argues that the risks to the environment can be solved through technology, as long as economic growth remains.

This idea is the essence of the green economy and is reflected in the report of the United Nations Environment Programme in Rio+20 (UNEP). There is no need to choose between development and sustainability, both are possible at the same time, it is the updated version of the Brundtland Report. The green economy, therefore, has the disease at its root: it does not recognize that on a finite planet, continuous economic growth is impossible, according to the three members of Ekologistak Martxan. “They also want to develop the green economy through the market,” they added. The UN, for its part, has underlined the importance of private space in the development of the green economy. They want to encourage companies to “pack up” by saying that they have a new business space at their disposal.

In a statement in which Ekologistak Martxan expressed his position at the Rio summit, he said that “it is significant that the big companies pay more attention to the conference than the governments themselves.” The reason is that, in the end, the industry will control the green economy. “These companies are already rubbing their hands of joy at the business opportunity that the green economy will give them.”

Who will control the green economy? the report explains it in detail. They say that the largest industries in the world are positioning themselves well for the fight against biomass, which is one of the axes of the green economy, as we will soon see, and that they are accumulating land and natural resources, while developing technology to convert substances of plant origin into industrial products. One of the consequences, according to ETC, is that nature becomes a market issue.

Biomass instead of oil

In the progress of the report, ETC presents the green economy as follows: “The idea is to replace oil with biomass (crops, prairies, forests, vegetable oils, algae...). The proponents of the idea foresee a post-oil future in which industrial production, instead of relying on fossil fuels, derives from biological raw materials.” And what place do new technologies have? They will be an essential tool for biomass to become a venal product.

The biggest biomass stores are in the countries of the so-called Global South, and the companies, of course, in the North. According to ETC, the green economy will lead to “greater absorption of resources over the past 500 years”. Moreover, the process has already begun. The data is provided by the ETC itself, after recognizing that the data may not be entirely accurate due to the lack of rigor in the investigations: Between 50 and 80 million hectares have been purchased by international investors, two thirds of them in sub-Saharan Africa. In 2006, 14 million hectares, 1% of the world’s agricultural area, were used for the production of biofuels. By 2030 this rate could rise to 4%, according to some studies.

Alleged technological solutions

In the opinion of the environmentalists, as we have already said, the agreements to be drawn from Rio+20 can only be a failure if they are based on the green economy. The most efficient technologies are not enough to curb the increase in consumption inherent in the logic of growth. “Today we are much more efficient than before, using both matter and energy,” says Ekologistak Martxan, and yet consumption has increased. In addition, it has been demonstrated that there is a rebound effect: achieving more effective processes in the use of a resource can lead to greater exploitation of this resource”.

Starting from this point of departure, the environmental groups are clear that the new technologies presented as miraculous solutions will not solve anything and will also generate impacts. "Governments and businesses try to avoid problems, rather than deal with them. Thus, instead of reducing CO2 emissions, carbon capture is proposed; if fossil fuel reserves start to run out, rather than reducing energy consumption, techniques such as fracking are developed to reach new deposits; although industrial agriculture is shown to be one of the main causes of climate change, rather than resorting to the ecological model, uncertain methods such as direct planting are put in place...”

On these pages we are familiar with some of the technologies that the UN concept of the green economy places as a solution to ecological and social problems. Nanotechnology, for example (see Cube 2.320 Light. ). Or transgenic. The threat of geoengineering is also present, although at the moment it falls asleep (see side page table). Others are not so famous. Here are a couple of examples:

Biomalo

Giving the word "biochar" in English with the Basque graph creates a game of words. Biomalo is the coal obtained from the pyrolysis of organic matter, that is, burning this matter in the presence of very little oxygen. Its advocates say that the land to which this type of coal is added retains carbon and thus reduces the impact of climate change. As if it were not enough, biomalo is also a fertilizer. Two benefits instead of one.

However, several studies have refuted each other. The so-called fertilizer, after two harvests, inhibits plant growth and in terms of carbon conservation, biomalo is degraded and poured into the atmosphere much faster than companies say.

Direct seeding agriculture

This is what is called the unburned crop. The Monsanto company states that FAO, the UN Food and Agriculture Organization, ratifies that with this system the soil gets more carbon, so less is emitted into the atmosphere. The Intergovernmental Organisation for Climate Change (IPCC), for its part, has expressed doubts about this.

Instead of ploughing the soil to remove so-called weeds, as has traditionally been done and done, direct planting is based on the use of herbicides. No wonder he approaches Monsanto. Today, about 100 million hectares are cultivated, mainly in America, to plant plants designed to resist the herbicide Roundup. It's going to be economics, but green isn't.

Ekologistak Martxaneko Iñaki Barcenak, Nerea Gonzalezek eta Rosa Lagok kontatu digutenez, duela hamabiren bat urte Kofi Annanek, artean NBEko idazkari nagusia zela, Global Compact estrategia jarri zuen abian, garapen jasangarrirako gobernuek ematen ez zuten dirua enpresa transnazionalek eman zezaten. Neurria borondatezkoa zen, eta esan gabe doa, porrot egin zuen.

Rio+20ko agendan dagoen gaietako bat Giza Erantzukizun Korporatiboari buruzko hitzarmena da. “Euren irudi kaxkarra berdetzeko eta kritikak desaktibatzeko bide bat da”, ekologisten ustez. “Interes publikoa egon beharko litzateke ororen gainetik, eta hala, enpresek derrigorrezko arauen arabera jokatu beharko lukete, gobernuek herriaren kontrolpean ezarritako arauen arabera”. Ez dirudi horrelakorik aterako denik Riotik.

Ekologistak Martxanek dituen beste proposamenak ere nekez ikusiko ditugu gauzatzen. Aipatzekoak, horien artean, Ingurumenaren Mundu Agintearen eta nazioarteko Ingurumen Epaitegiaren sorrera. Lehenbizikoak eskumena edukiko luke isunak jartzeko, eta bigarrenak gobernu zein enpresak epaitzeko.

Beste proposamen batzuek ekonomiarekin zerikusia dute, interesik gabeko moneta-sistema sortzea adibidez. Horretaz gehiago jakin nahi duenak 2011ko ekainean aldizkari honetan Pedro Prietori egindako elkarrizketa irakurtzea dauka (Argia, 2.279 zenbakia).

ETCren Nork kontrolatuko du ekonomia berdea? txostenak atal bat eskaintzen dio itsaso, laku eta ibaietako biomasaren erabilerari. “Kostaldea duten estatuak ari dira, dagoeneko, ekonomia berdearen uretako baliokidea sustatzen: ekonomia urdina”. Ur-biomasa landare zein animaliek osatzen dute, baina gaur egun industriak batez ere algak erabiltzen ditu. 2008an hamasei milioi tona ekoitzi zituzten; kopuru horren zatirik handiena elikagai modura saldu zen, baina hidrokoloide izena daukaten substantziak ekoizteko ere erabili zen. Mikroalgena, berriz, oso merkatu txikia da oraindik, elikagaien osagaiak sortzeko bideratua batik bat.

Algak oso erakargarriak izan daitezke biomasa industrialerako lehengai gisa, hainbat ezaugarri berezi dituzte eta. Esaterako, oso azkar hazten dira; barietate batzuk 60 zentimetro handitu daitezke egun bakarrean. Bestetik, kopuru handitan ekoitzi daitezke leku txikietan. Alga mota batzuek metro koadroko eta urteko 16 eta 65 kilogramo bitarteko biomasa sor dezakete. Lehorreko labore emankorrenek 6-18 kilogramo bitartean eman dezakete denbora eta espazio berean.

Aspaldikoa da algak bioerregai bihurtzeko asmoa, oraingoz merkatuan arrakasta eskasa izan badu ere. Nolanahi, berriki sortutako zenbait enpresak erronkari helduko diote, ETCren arabera.

Nagoyan (Japonia) 2010ean sinatutako Aniztasun Biologikoaren Hitzarmenak moratoria ezarri zion arren, geoingeniaritzaren ideiak ez du indarrik galdu. Britainia Handiko Royal Societyk honela definitzen du: “Gizakiak eragindako klima aldaketa antropogenikoari aurre egiteko planetaren ingurumena eskala handietan manipulatzea”. Bi bide leudeke horretarako: atmosferatik C02 erauztea, edo are ikaragarriago dirudiena, eguzkiaren erradiazioa kontrolatzea. Adibide bat: azken unean bertan behera utzi zuten esperimentuan, ikerlari britainiarrek ura bota nahi zuten atmosferara, kilometro bateko altueran, tantek eguzki-izpiak islatu eta lurrera iristea eragozteko.

AEBetan, zenbait zientzialari eta militarrek gobernuari gomendatu diote moratoriari kasu egin ez eta geoingeniaritzaren alorrean ikerketa sustatzeko, “beraiek egiten ez badute beste norbaitek egingo duelako”. Txinak, bere aldetik, %10 gehitu nahi du euri kopurua, uzta hobeak izate aldera. Eta horretan ari da.

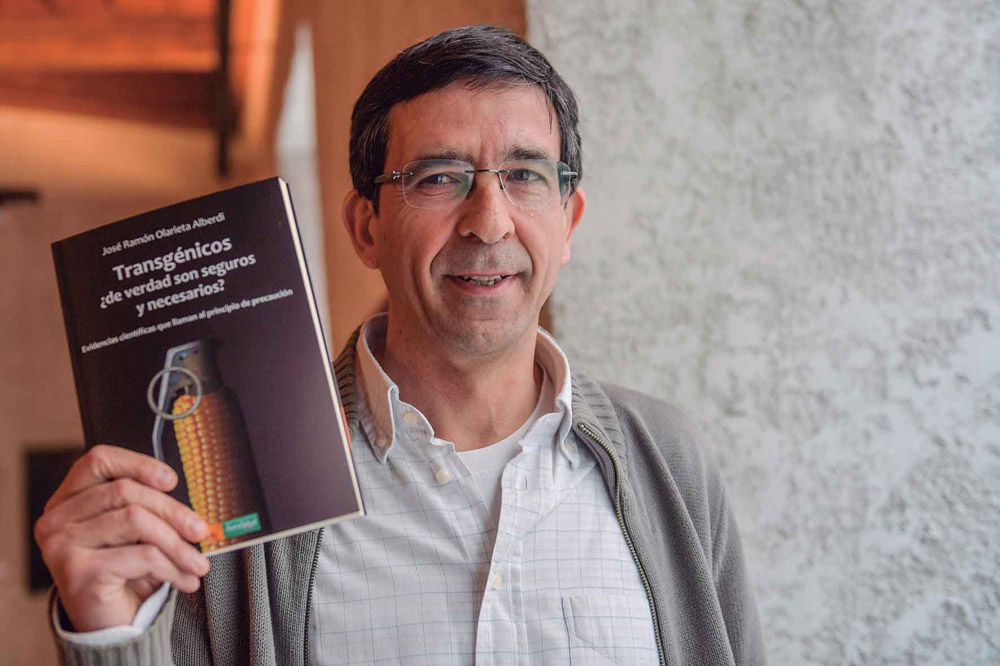

José Ramón Olarieta Alberdi is a doctor in agronomist engineering and professor at the University of Lleida, as well as a member of the Catalan association Som what Sembrem.El last year published a book on transgenics: Are GMOs really safe and necessary? In April, Leitza and... [+]

Laborantza-industrian egin den inoizko akordiorik handiena gelditzeko eskatu diote milioi bat lagunek Europari: Monsanto eta Bayer enpresek indarrak batuko dituzte galarazi ezean. Hazi transgenikoen eta industria farmazeutikoaren arteko lotura 2016tik datorren arren, azken... [+]

Europako Batzordeak iragarri du sakon aztertu nahi duela Bayer konpainiak Monsanto erosteak kalterik egingo ote dion pestiziden eta hazien merkatuari. Bruselak adierazi du fusio-operazioa burutzeak bi arlo horietako munduko enpresarik handiena sortuko lukeela, eta horrek... [+]