From house to place, scream and fight

- After years of exile in the Republic, it was held in secret for many years. Half a century ago, however, he jumped from Itsaso to the entire Basque Country. Celebration and struggle, claim and debate. The Aberri Eguna has become a political thermometer to measure the fires and frost of Basque nationalism.

The photograph of Ximun Haran and Julen Madariaga in front of the Gernika oak (on the next page) is well known. It represents the essence of the 1963 Aberri Eguna at sea: One, ETA, the other, publicly claiming that Euskal Herria is a nation. This event at sea is considered a milestone, but it had an antecedent in 1962, exactly half a century ago.

Enbata members organized the unofficial Aberri Eguna in 1962, also in Itsasu. It was the starting point for organizing the big event of the following year: “Last Easter Monday a congress has been held. It has passed through all unity and all fraternity. A warm day, a beautiful day, full of rich holes! It is possible that the facts and the works will soon also appear! Let’s go ahead!” said Enbata magazine.

Ximun Haran, Jean Luis Davant and Jaques Abeberri spoke at the Aberri Eguna of their beginnings before a multitude of political exiles, including Telesforo Monzon. Abeberri raised different options about Enbata’s future: Is it a political party, a clandestine resistance or a broad nationalist movement? The latter was what they had supported. You might think that this decision has something to do with the success of next year’s Aberri Eguna.

On the other hand, that was the 25th anniversary of the Gernika bombing, and they remembered it very well: “This terrible war has not been known by the youth of the present. It is good to know what the parents did for the People and what they suffered… But above all, he cares about the future and cares about the creation of a heart of thought: An Euskadi and how he will see it free. What do all the other projects matter?” says Enbata.

Thirty years passed since the first Aberri Eguna republican; thirty years and a war. During all this time, the homeland days were held inside the house. On Easter Sunday, the father taught his children an ikurrina with letters from JEL, taken from a misal in Orixe in Basque, and surrounded by swords and dancers who satisfied nostalgia in the Basque houses of the foreigner. No more.

However, in the late 1950s, criticism of the passivity of the PNV was increasingly minuscule. They accused the old Jeltzales of looking back and being OK there. “Dear father, I am already of age…”, wrote an anonymous author in EGI’s Aberri magazine: “Youth has the right to make their revolution… you could rest a little… will you let me help?” From that rupture came ETA and nationalism took a fresh air. The new generations, to the Gu tour Euzkadiko gaztedi berria de Labegerie, pushed the nostalgic.

That is, in part, what represented the 1963 Aberri Eguna, the envy of a part of the youth: “Insane behaviour has spread in our country: The motto ‘not yet’ is a good example of what madness is,” ETA explained in its writing that day. From there, the days of homeland fell into a new dimension, became a day of mass demand.

For party or for struggle?

The days of the Francoist homeland paved the way for the struggle. But within nationalism there were very different perspectives. Most of those who gathered around the PNV wanted “peaceful exhibitions”, while ETA considers that “the Aberri Eguna is not a folkloric festival, for that there are romerías”.

In 1964 the PNV called Gernika at the Aberri Eguna. It is the first time that a public act has been held in Hego Euskal Herria since the end of the war. The PNV felt obliged to take that step, in order to maintain its hegemony in nationalism. ETA also called Gernika, as well as other institutions. According to the correspondent of Euzko Deya, 40,000 people met there, under the umbrella, “keeping respect and order”. Somehow, the PNV achieved the goal: it was a great and peaceful demonstration.

In 1965 what was done in Bergara was exactly the same, but from there the tension of the days of homeland grew and the metaphorical “battle” became a literal struggle. The 1968 Aberri Eguna reached its peak: We can read “San Sebastian, besieged by land, sea and air” in the headlines of Basque newspapers abroad. The Franco Government was determined to put an end to the Basque rebels and to this end it began a “hot war”.

That same year the clashes and shootings with ETA increased; the year in which Txabi Etxebarrieta was killed, the year in which Meliton Manzanas was killed. In Donostia-San Sebastián, on 14 April, thousands of police officers – 500 of them on horseback – cut roads and bridges, forced bars to close and there were about 300 arrests. It was the first time that citizens faced the security forces.

It was a year of inflection. The PNV considered that in this situation it was not possible to organize anything and called its followers to boycott the 1969 Aberri Eguna. The strategy for the following years was also similar: “Don’t play the regime,” in the words of your colleagues. The institutions on the left of the PNV thought the opposite and continuously accuse supporters of issuing slogans to demobilize: “This year the police have not had to intervene, an unexpected colleague has facilitated the work,” said De Mayo, 1969, the ETA body.

However, the PNV was ambiguous about the violence against Franco. He defended pacifist, but not monolithic, positions. The EGI militants were constantly moving to ETA, since, faced with the paralysis of the PNV, the armed organization provoked a great fascination. To avoid this, the PNV granted EGI some permission to carry out armed actions. Jokin Artajo and Alberto Asurmendi were members of EGI.

After the years of the Transition, the debate on the nature of homeland days was revived. On 28 October 1979 the Gernika Statute was adopted and shortly thereafter the Basque Parliament and the Basque Government were set up, with Carlos Garaikoetxea as lehendakari. The PNV met the closest aspirations and began to celebrate the Aberri Eguna in a festive atmosphere: “Euzkadi is 365 days a year ago,” says a sticker at the time.

But the calls of the leftist parties and the Basque organizations will continue to be revolutionary and a good example of this was what happened in Pamplona/Iruña in 1980. HB, LKI, EMK, LAB, ETA(m) and even the US at the last moment called Pamplona that year. The government banned the act and threatened to use force, encouraged by the right-wing sectors in Navarre. However, the organizers did not suspend the Aberri Eguna.

The one in Pamplona recalled the hardest years of Francoism, an exceptional police occupation and indiscriminate aggressions: “Above the Txandia and the extra food, the wood was more abundant in the Basque Country. There is too much demand for the Basque Country to acknowledge that it has reached a stage on its path to freedom,” wrote the chronicler of Punto y Hora.

After Easter Sunday, Jose Luis Alvarez Enparantza Txillardegi pronounced the blackest in a letter to the Egin newspaper against the PNV: “The PNV has celebrated with laughter, screams and chocolate the Aberri Eguna, ignoring the Aberri Eguna of Navarra. The cycle that began on 25 October is therefore a milestone, and the PNV has moved on to the side of the enemy.”

Aberri Eguna, what day?

The Aberri Eguna was held for the first time as an official holiday in 1982. By then, however, the Socialist Party was no longer involved in the events of that day and the calls of the Communist Party of the Basque Country were increasingly confusing. The Aberri Eguna of the dictatorship were not only patriotic festivities, but also days of reclaiming the working class. However, in the 1980s, the view of the leftist statalist parties towards the Aberri Eguna was changing, as the party was increasingly “exclusive”. Last year, in 2011, the representative of PSE-EE Txarli Prieto announced on the occasion of Aberri Eguna that: “The Aberri Eguna is a crazy race of abertzales, to see who is more pro-independence and more radical.”

ETA was defined as a socialist in 1965. Undoubtedly, this institution was the channel of approach to nationalism for many workers on the Spanish Left. The clearest example could be the Burgos process of 1970. As a result of this case, ETA and the Basque resistance received numerous supports and the sectors of the Spanish Left took on various demands, such as amnesty or self-determination. Moreover, the more left-wing, Abertzales and Spaniards today had the Aberri Eguna as anti-imperialist and anti-capitalist and strongly criticized the PNV for being representatives of “bourgeois nationalism”.

The first democratic elections, from then on, took the filter of anti-Francoism from the Aberri Eguna and then realized that the PSOE and the PCE were not so Basque and did not love the rights of small peoples. Originally, Euskadiko Ezkerra, who had a lot of the Abertzale left, continued to celebrate the Aberri Eguna on his own, but with less and less force, and in 1993, coinciding with the PSE-EE, they proposed to change the celebration of Easter Day to October 25. Precisely, two decades later, the PSE-EE, with the support of pp, has set that date as the Christmas festival.

At the same time yes, but not mixed

The fingers of the two hands are left to count the unified Aberri Eguna celebrated in half a century: 1964 in Gernika and 1965 in Bergara; 1967 in Pamplona; 1978 and 1979 in the capitals; and 1999 and 2000.ean in the municipalities called by Udalbiltza.

The one that received the most support was that of 1978. The other parties, with the exception of AP and UCD, called the spokesmen of the groups in the House. According to the newspapers, more than 200,000 people met in the four capitals of Hego Euskal Herria and Mount Larrun. Anyway, at the same time, but not confusingly. Very different messages were heard in the demonstrations and, in some cases, there were also incidents among the supporters of the party.

Another significant date was 1999. The joint call was made by Udalbiltza and hundreds of thousands of people concentrated in front of the town councils. In the afternoon, each organized its own act. The following year, the initiative was taken by the institution of municipal voters, but by then the relations between the Basque forces had been broken by the failure of the Lizarra-Garazi agreement and the return of ETA to armed activity.

ETA's activity has always been at the centre of the organization's whirlwind and the speeches of the days of the country, when expectations of peace arise. In 1989, the Algiers negotiations reached the Aberri Eguna of that year, as the ETA ceasefire ended on Sunday. The HB gathered thousands of followers in Pamplona, but Jon Idigoras said that this multitudinous Aberri Eguna was not called to “influence Algiers.”

The murders of ETA have also marked the passing of a few days of homeland. In 1976, the first post-Francoist Aberri Eguna, all parties – PSOE, PNV, LKI, EKA and some leftist Abertzale parties – were preparing to make a joint march. But a few days earlier ETA had kidnapped and killed the businessman Ángel Berazadi, and the PNV, the PSOE and the Basque Government in exile kept the Pamplona quote. In 1997, the lifeless body of ETA member Josu Zabala appeared in a camp in Itziar and the Aberri Eguna was impregnated with suspicions and complaints about the dirty war.

But not only the armed conflict and the attacks, but the Aberri Eguna has been a reflection of the debates of the time: The Statute, the right of self-determination, Navarre, the Basque Country, Lemoiz, the economic crisis, Itoiz… The choice of the place has also had a great symbolism, as when in 1967 Pamplona was called, as an expression of territoriality: “Don’t forget that, in Navarre, Pamplona is the capital of the Basque Country in its own right,” said the PNV that year – the Arana party still had a lot of weight in Navarre in those years, as seen in that Aberri Eguna. The PNV did not convene Gernika by chance in 1964, nor did Herri Batasuna in 1987, coinciding with the 50th anniversary of the Gernika bombing.

Above all, the Aberri Eguna has been an instrument of claim: the ring to confrontation and the consensus table. At the same time as the greatest challenges, citizens have increasingly shown muscle strength through the celebration of the Aberri Eguna. This was the case in the Franco regime against the dictatorship, in the Transition in favor of self-government, or in the time of Lizarra-Garazi saying “we are a nation”.

The days of the homeland of Itsasu in 1962 and 1963 represented a change of cycle in the course of this celebration. Over time it will be seen if a new cycle change will occur soon, for which the following elements are not missing: The end of ETA, a new sovereign political majority, the referendum projects in Scotland and Catalonia… And above all: a huge economic crisis that has revealed our strengths and weaknesses.

1963:”Itsasuko Ageria”. Gerra osteko lehen Aberri Egun publikoa.

1964:Gernikan milaka lagun elkartu ziren EAJ eta ETAk deituta. Haritzaren aurrean makurtuta dagoen gaztearen irudiak munduari bira eman zion (Argia honetako azala).

1966:ETAk Irun-Hendaiara deitu zuen bere kabuz, Aberri Egun iraultzaileagoa bultzatzeko asmoz.

1969: Aurreko urteko errepresioaren ondorioz, EAJk ez zuen deialdi publikorik egin. Boikot urtea.

1974:Leizaola lehendakaria Gernikan izan zen.

1978:Lehen Aberri Egun legala ospatu zuten alderdi guztiek elkarrekin.

1980:Herri Batasunak eta beste zenbait alderdik Donostian deituriko Aberri Eguna galarazi zuen Espainiako Gobernuak.

1982:Lehen Aberri Egun ofiziala. Alderdi estatalistek jada ez dute ospakizunerako deialdirik egingo.

1987:Zatiketa EAJn. Eusko Alkartasunak Anoetako Belodromoan egin zuen ekitaldi nagusia.

1989:Herri Batasunak 60.000 lagun elkartu zituen Iruñean autodeterminazioaren alde. Aljerreko negoziazioek porrot egin zuten.

1995:ELA eta LAB sindikatuek komunikatu bateratua plazaratu zuten. Hiru urte geroago beste agiri bat kaleratuko dute. Sindikatu abertzaleen arteko aliantzaren hasiera.

1999:Lizarra-Garaziko akordioa. Udalbiltza udal hautetsien biltzarrak deituta Aberri Egun bateratua egin zuten udalerri guztietan indar abertzaleek.

2002: AB, Aralar, Zutik, EA eta Batzarrek agiria kaleratuko dute ETAri su-etena eskatuz. Aberri Eguna nork bere aldetik ospatu zuen.

2010: Independentistak sareak Irun-Hendaian 14.000 lagun elkartu zituen. EA, ezker abertzalea, LAB, Nazio Eztabaidagunea eta beste hainbat eragileren babesa izan zuen. 2012an Iruñean egingo du Aberri Eguna eta Aralar, Alternatiba eta AB ere gelditu dira deialdira.

1976an Hitz aldizkariak Aberri Egunaren Ipuia komikia kaleratu zuen. Marrazkiak Jon Zabaletak egin zituen “Akullu” ezizenarekin eta testua Beñat Bidegorrirena da. Bertan azaltzen da nola antzina bazen herri bat pozik bizi zena. Behin batean barbaroek eraso egin zuten eta herritarrak zapalduta bizi ziren hortik aurrera. Halabaina, gauetan akelarreak ospatzen hasi ziren isilpean, gero armak hartu zituzten, eta azken borrokaldiaren ondoren barbaroek amnistia eskatu behar izan zuten eta ihes egin. Geroztik ospatzen omen dira aberri egunak.

Until now we have believed that those in charge of copying books during the Middle Ages and before the printing press was opened were men, specifically monks of monasteries.

But a group of researchers from the University of Bergen, Norway, concludes that women also worked as... [+]

Florentzia, 1886. Carlo Collodi Le avventure de Pinocchio eleberri ezagunaren egileak zera idatzi zuen pizzari buruz: “Labean txigortutako ogi orea, gainean eskura dagoen edozer gauzaz egindako saltsa duena”. Pizza hark “zikinkeria konplexu tankera” zuela... [+]

Ereserkiek, kanta-modalitate zehatz, eder eta arriskutsu horiek, komunitate bati zuzentzea izan ohi dute helburu. “Ene aberri eta sasoiko lagunok”, hasten da Sarrionandiaren poema ezaguna. Ereserki bat da, jakina: horra nori zuzentzen zaion tonu solemnean, handitxo... [+]

Linear A is a Minoan script used 4,800-4,500 years ago. Recently, in the famous Knossos Palace in Crete, a special ivory object has been discovered, which was probably used as a ceremonial scepter. The object has two inscriptions; one on the handle is shorter and, like most of... [+]

Londres, 1944. Dorothy izeneko emakume bati argazkiak atera zizkioten Waterloo zubian soldatze lanak egiten ari zela. Dorothyri buruz izena beste daturik ez daukagu, baina duela hamar urte arte hori ere ez genekien. Argazki sorta 2015ean topatu zuen Christine Wall... [+]

Kirola eta oroimena uztartuko dituzte, bigarrenez, mendi-martxa baten bitartez. Ez da lehiakorra izanen, helburua beste bat delako. La Fuga izeneko mendi martxak 1938ko sarraskia gogorarazi nahi du. Ezkabako gotorlekuan hasi eta Urepelen amaituko da. Maiatzaren 17an eginen dute.

Bilbo, 1954. Hiriko Alfer eta Gaizkileen Auzitegia homosexualen aurka jazartzen hasi zen, erregimen frankistak izen bereko legea (Ley de Vagos y Maleantes, 1933) espresuki horretarako egokitu ondoren. Frankismoak homosexualen aurka egiten zuen lehenago ere, eta 1970ean legea... [+]

Fusilamenduak, elektrodoak eta poltsa, hobi komunak, kolpismoa, jazarpena, drogak, Galindo, umiliazioak, gerra zikina, Intxaurrondo, narkotrafikoa, estoldak, hizkuntza inposaketa, Altsasu, inpunitatea… Guardia Zibilaren lorratza iluna da Euskal Herrian, baita Espainiako... [+]

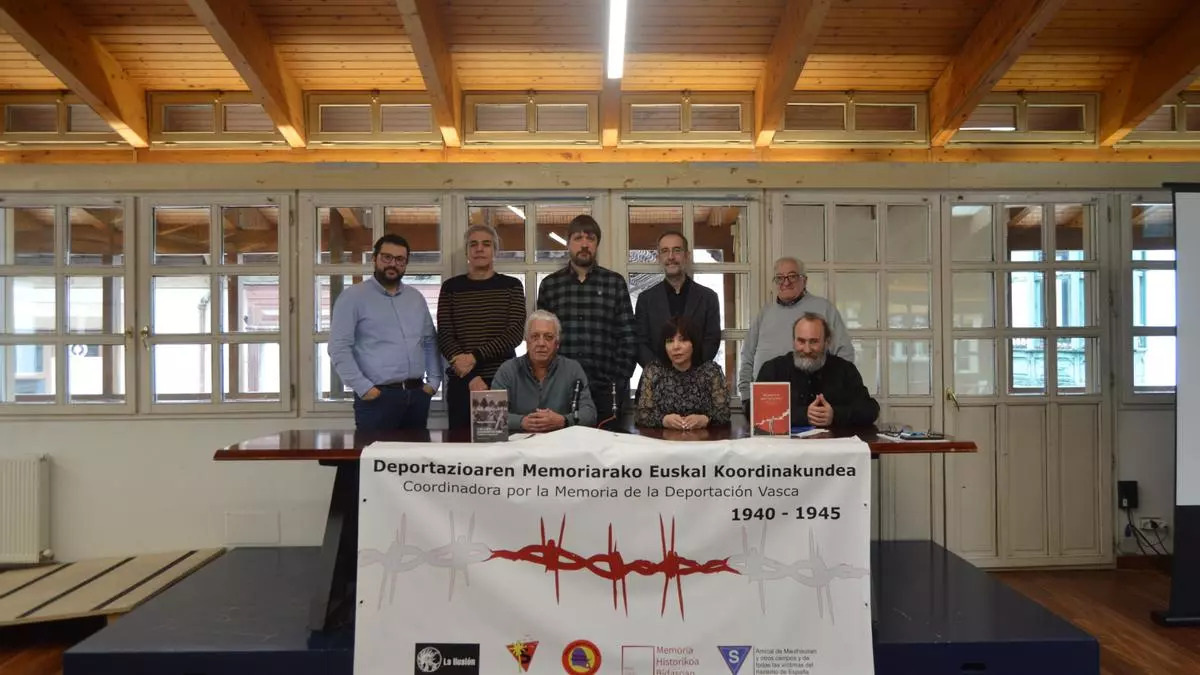

Deportazioaren Memoriarako Euskal Koordinakundeak aintzat hartu nahi ditu Hego Euskal Herrian jaio eta bizi ziren, eta 1940tik 1945era Bigarren Mundu Gerra zela eta deportazioa pairatu zuten herritarrak. Anton Gandarias Lekuona izango da haren lehendakaria, 1945ean naziek... [+]