A tradition that has crossed borders

- Between the Spanish and French states, smuggling has been a common practice in the Basque Country. To address this important part of history, we have asked the same protagonists, the men and women who worked during the night.

“Once, the pots told him that he had to take the ram off for smuggling a man from Etxalart to Sara with a ram: “I smuggled? No man, he has escaped... You know, love.” The ram told them that he had escaped from the thorns to Sara and that he had gone to look for her,” says Gau lana. Smuggling books in the Bidasoa area.

“It was compensation, a citizen response to abuses imposed by states or authorities.” Rosa Arburua joins these words of the writer Robert Bresson when he talks about a smuggling that has had a long and fruitful tradition in the Basque Country. The writer Bidasotarra has just published the book Gau lana, a work driven by the desire to delve into the anecdotes about the smuggling he has heard at home since his childhood. He has lived the subject very closely, as his father and his two brothers, Etxalarko, have worked on smuggling, “in the twentieth century. In the 15th century, like most of the surroundings of the Bidasoa”.

Smuggling or night work exists from the establishment of borders, customs and payment centres. According to the French writer André Besson, smuggling is as old as civilization. Across borders, the authorities decided which products they could pass and which they could not, and also allowed certain quantities. After the Spanish Civil War, for example, in Hegoalde there was no white bread and Sara was smuggled into Etxalar. “How could they ban bread if needed? Isn’t that an abuse?” says the Arburua. In the case of customs, an amount of money had to be paid to pass the products. In Navarre, in the Middle Ages, they were called “table” and had the toll function of the current highway. For these reasons, smuggling was initially done to meet the needs and avoid the above payments. Subsequently, even to obtain an economic benefit. “What did you want? It was the way to make money. How can we not do that? It is clear that we could do nothing more.” They're words from Ernestine de Urruña, who doesn't want the surname to be published. He has also been in smuggling for many years, but he wanted to make it clear that “if we hurt someone, we did it wrong to the states.”

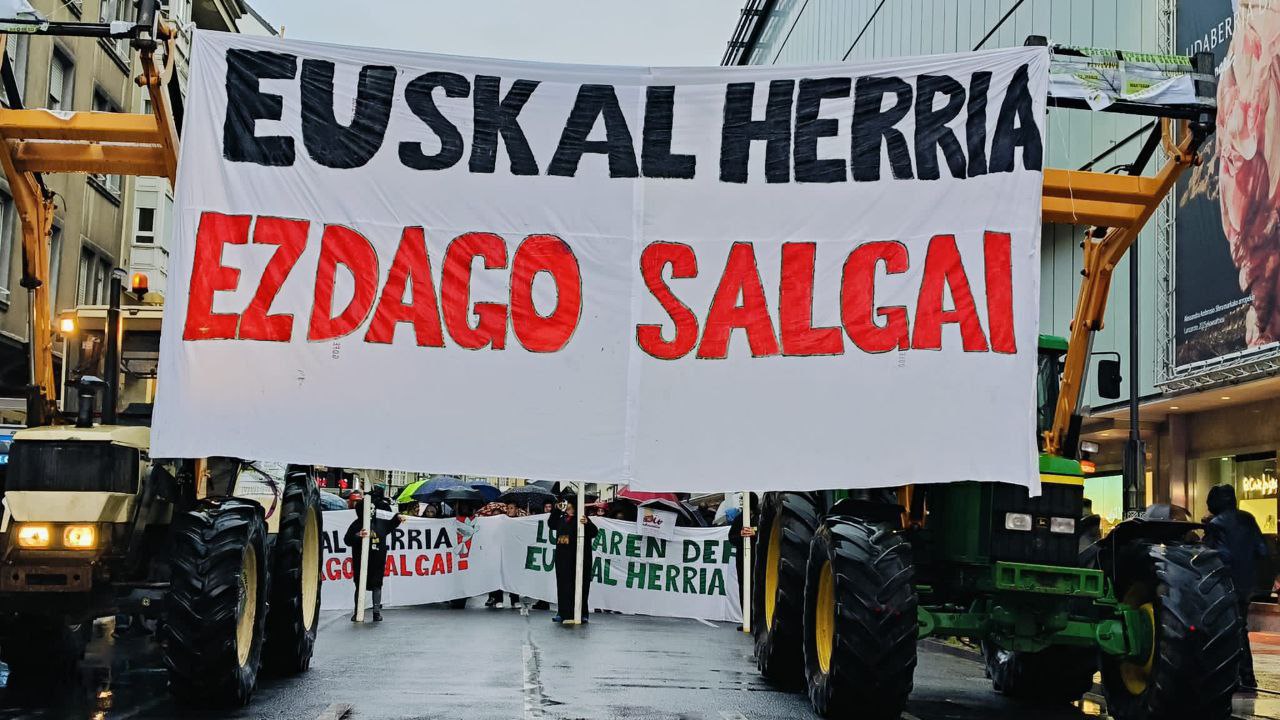

Euskal Herria offers very favourable conditions for smuggling, particularly in the Bidasoa area. "It has been a physical, political and administrative constraint. There have been a lot of smuggling in a few kilometers. In other areas there have also been similar movements, but smuggling has been the main thing over here.” The mountains and the river and the sea offer a unique opportunity for smuggling.

Smuggling has been done with bread, factory parts and transport, fish, coffee, tobacco, beverages, clothing, condoms, TVs, almonds, sockets, animals, money, gold... From North to South and vice versa, the performance has been bidirectional. The political and economic situation at the time affected both the products used for smuggling and the quantity. For example, at the time of the Carlist Wars, weapons were taken by sea.

Passing alcohol through Ibardin

Ernestine started smuggling at the age of 18: “At that time I worked in the fish factory and as I now lived next to Ibardin, I was asked if I would bring some bottles of alcohol to Urruña, and I accepted it. So I started bringing Ricard, Porto and Martin de la Venta, first by bike and then on the mobile phone. Before arriving at the customs office (the customs office next to the country house where he lived), he kept the parcels in the ditch and returned home passing through the customs office. Then he walked back to pick up the packages.” Ten guards guarded the customs.

In addition to alcohol, the laboratory has gone through different products and for this, it had the collaboration of the brothers Lino, de Bera, and Juan Luis Etxegarai, among others. “The bearings were taken from Yugoslavia of the time to the warehouses in Paris and from there to San Juan de Luz. On Saturdays in the afternoon I went looking for her with my son Frederic and took about 700 kilos at the Renault, where we had agreed with Lino.” They spent one tonne a month in autumn and winter, while in summer and spring they engaged in clothing smuggling with Lino's brother, Juan Luis. They had meeting places in Biarritz.

However, those who are not products have also crossed borders and customs: ideas, for example. As Arburua explains, in the 18th century and after the French Revolution, European absolutist regimes did not want to introduce revolutionary ideas into their lands, but they passed. “They found fans with written messages.” Then, through the boats, the ideas of the Enlightenment traveled through America. “There was a time when there were spies as well and we had to be careful.”

Another type of smuggling was that of people who were dedicated to helping people cross the border. Normally, they were engaged in other smugglers and, by the way, people were also there. Those who, with clandestine help, managed to cross the border include the aristocrats, the Jews, the nationalists, those who attacked the Germans in the Second World War and the Portuguese who wanted to work in France.

As for the latter, there was a great emigration between 1960 and 1974. “It is said that at least one million people left Portugal, of whom about 800,000 went to work in France.” At that time the dictator Salazar was in power, who, although he did not prevent the obtaining of the passport, placed impossible conditions for this. On the other hand, Portugal was at war with its colonies and wanted young men to fight. The misery and unwillingness to go to war were the main reasons for escaping the country. In France, on the other hand, there was work and they were very happy to welcome the Portuguese, “because they were very fine and persevering workers, Catholics and Whites.” To do so, the Basque double bassists had to cross 2,000 kilometres and two boundaries, including Ernestine, who has been a direct witness.

However, among the smugglers there was some apprehension of people smuggling, as can be seen from the words of Arburua: “My grandfather always told my father not to pass weapons or people, because guns kill people and people talk.” He adds that there was a code of ethics among smugglers, although there would always be someone who would not respect. However, the smugglers knew perfectly well who had not done things and since then others looked wrong.

The people as a collaborator

Some of them started smuggling very young, in some case at the age of 10. In any case, it was most common to start between the ages of 13 and 16. “The children were not engaged in packages, but they did send messages to the dwellings and see if the roads were free. In the process of moving from child to man there were two important moments: communion – and with it leave the shorts and wear the long pants – and initiation into smuggling. With the load they took long walks, but for them that was very important, something that honored them. And even though they were exhausted, they kept going,” explains Rosa Arburua.

The physical resistance that was needed to mount the mountain packets was very great, so the men have been the ones who have walked the mountain the most. Women had other needs: making packages and storing them, monitoring, sewing double depth vests, going to collect, signaling… “It has been women who have had a lot of money hidden in their bodies”, some of them in the Behobia environment. For example, the women of Hondarribia worked with fish and angulas. Arburua has recalled that Aginaga's angles were brought from Brittany and were later downloaded in Hondarribia and placed in packages to take them to Donostia or Aginaga by taxi or bus. In addition to angulas, hake from Hondarribia has also passed to Hendaia.

Smugglers were structured to work, forming a network of different levels. The first level people brought the necessary products, bought them in bulk in one place and sold them retail in another. As for second-order smugglers, they were normally partners and had peones, collaborators: they distributed the products purchased from crews of ten to twelve smugglers, who passed them from one side to the other.

However, beyond the gangs, the family, the people and often the whole community were submerged in smuggling, even the animals! In Zugarramurdi, for example, dogs acted as whistleblowers. If the cocos (civilian guards) were located in the vicinity of the caserades, they started on the slopes so smugglers could locate the site of danger. The fact that the whole society was in the salsa was that smuggling was seen with good eyes, since it was not an activity of a few, but of the people.

To avoid pots or guards, various strategies were used, perhaps the most common ones. “Some on the grass put a sheet or a white cloth to indicate that the road was free. It was also very common to mimic the sounds of the animals that were communicating with each other, like the sound of the goat, the sheep or the flame. In addition, each had its own way of mimicking this animal and knew who it was calling,” Arburua explains. Lino Etxegarai of Bera told us that in his crew they were called imitating the sounds of sheep. However, it was not the smugglers who used the tricks: “The civil guards put a black thread on the roads at a height and if it was broken they knew people were going around,” says the Bera smuggler.

A means to meet needs and earn money

The money collected by smuggling varied according to the time, the distance to travel and the product. Ernestin received 200 euros a month for spending alcohol in winter and 500 in summer; “for me it was the same as the work wage,” he tells us. For his part, Etxegarai, who then took about 5 euros a month in the quarry of Irun, with the smuggling gained about one euro per night and “if the burden was heavy they paid a little more”. Finally, if the contraband were passed six or eight times, they would take out the wage that was earned every month at the factory at that time.

As an illegal activity, smuggling was subject to penalties if the capture took place. In any case, depending on the historical moment, the material of the smuggling and the quantity, the punishments varied. In the event of being intercepted with food, the food was not normally required, but simply a fine was imposed. In the case of animals, the most frequent penalties were confiscation and the imposition of a fine, although there was also a risk of being sent to prison occasionally. The worst thing, though, was to intercept people. “If they were held in Spain with Portuguese, they had to spend nine months in prison; in France they were not punished because the Portuguese were asked to work there,” explains Ernestin.

To avoid punishment, different means were used and one of them was buying pots. According to Arburu, “Portuguese smuggling was barely done, but with packages it was done. The pot was bought that warned the smugglers of their location, so the smugglers knew where they would not go.” However, according to Etxegarai, some denounced them after they had bought them, but they knew immediately who it was. In the case of the gendarmes and the guards, there were not many who accepted the bribe. But some people didn't like to buy from the police, including Ernestin. “Never notice those who have the clothes that others have given them!”

The Arburua report points out that smuggling was a business for all and that, in essence, it was also of interest to the Spanish and French States. “For example, to start the factories, it was necessary to pass the flyers, so the ban was in part a sham. If he was confiscated, he took money, but given the number of tons that had passed, he didn’t take it that much.” However, the danger was there, and the sad anecdotes that occurred at the scene witness many wounded and dead.

Smuggling has united us.

Regarding the importance of smuggling in the Basque Country, Rosa Arburua has reflected on the following: “On the one hand, Euskaldunity on the sides of the border, Euskera and culture, and on the other hand, smuggling has united us, because it has had an authentic tradition.”

The stories about this rich tradition are known by people who have experienced smuggling in or around their families, and they talk about it naturally. “To a stranger, however, I would tell him that he was smuggling into his own family and would consider us as drug traffickers.” The Interior Minister has stressed that there is a risk that the next generations will not know anything about the issue. “In school, young people learn the adventures of kings, but not the history of the people, which is really worth knowing.”

In short, although there are publications and audiovisual media that collect testimonies, there is no monument or museum that stores the memory of smuggling. That's right, the cramps are standing. After the Peace of the Pyrenees, signed in 1659 by the crowns of Spain and France, which ended 30 years of war, the two states set the borders and set milestones along the border. Well, these same milestones that smugglers often used to orient themselves and as a reference, will be the ones who best know the circumstances of the smuggling and best keep their memory.

15 urte zituela hasi zen Berako Lino Etxegarai kontrabando lanetan, Juan Luis anaia alboan zuela. Ordutik urte askotxo pasa badira ere, ederki gogoratzen ditu garai hartan bizitakoak.

Juan Luis anaiak eta biok herentziaz jaso zenuten kontrabandoan aritzea, ezta?

Guk hori ikusi genuen txikitatik, gure ama Carmen eta Lino atautxi ere aritzen baitziren. Ez zen bertze lanik eta guretzat kontrabandoa beste edozein lan bezalakoa zen, garai hartako fabrika. Norbaitek erraten zizun zein ordutan eta zein lekutan behar zen pertsona bat zerbait pasatzeko, eta, gu han izaten ginen.

Gogoan al duzu kontrabandoan aritutako lehen eguna?

Mendiz lehen bidaia egin nuenean 15 bat urte izanen nituen. Ibardindik 20 kilo inguruko karga hartu eta Bidasoa aldera pasa beharra nuen. Pentsatu nuen “hau ez da niretzat”. Nire anaia Juan Luisek bost urte gehiago zituen eta hori aise ibiltzen zen; berak erakutsi zidan. Sos beharra genuen eta aurrera jarraitu behar!

Zerekin aritu izan zara kontrabandoan?

Abereen kasuan, behorrak eta mandoak Espainiatik Frantziara eramaten genituen, eta zekorrak Frantziatik Espainiara. Zientoka ekartzen ziren. Alkohola ere eramaten genuen garrafoietan, buruan pasatzen genituen. Gainontzean, errodamenduekin ere anitz ibilia naiz eta arraia, telebistak, kamioietako piezak, penizilina, puruak eta altzariak ere pasatu izan ditut. Halere, nik nahiago nuen paketeekin aritu aziendarekin baino, inoiz ez baitakizu abereek zer eginen duten.

Bera inguruan jende asko aritzen al zen kontrabandoan?

Hiru koadrila baziren, eta horietako bakoitzean hogei bat aritzen ginen nagusi batentzat lanean. Apaizak ere aritzen ziren kontrabandoan, baina halere eskas zenez, Irundik ere ekartzen zen jendea. Pentsa, guardia zibilen haurrak ere aritzen ziren!

Zenbateko maiztasunarekin egiten zenuen kontrabandoa?

Eskaeraren arabera aritzen nintzen, batzuetan egunero eta bertzetan bi edo hiru egunetan deus ere ez. Mendian aritzen nintzenean lanean, ilunabarrerako etxera joaten ginen eta bertan zein lan egin behar nuen abisatzen zidaten; orduan, afaldu, bokadilo bat hartu eta martxa! Batzuetan ilundu aurretik joan behar zen, bestetan ilundu eta segidan, edota gauerdi aldera, ez zegoen ordu zehatzik. Tartean gaueko bi bidaia ere egiten genituen. Zenbaitetan gogorra izaten zen, egunez lanean aritu eta ondoren kontrabandora joan beharra! Dena den, iluntasuna ez zen oztopo, gauez egunez bezala ikusten da-eta.

Behin guardia zibilak harrapatu eta apuru ederrak pasa omen zenituen…

Bai, belaunean egin zidaten tiro eta orain protesia dut. Urtarrilak 10 zela gogoan dut. Denak batera ginen, anaia tartean; eguraldi txarra zegoen eta lan asko eginda nuen. Goizetik gauza anitzekin aritu ginen alde batetik bertzera, eta azkeneko lana Ibardindik rosli puruak ekartzea zen. Hamabost lagun inguru ginen eta ni gibeletik joan nintzen hasiberria zen gazte batekin. Orduan gelditu egin nintzen paketeak ongi paratzeko eta botatik sartutako harria ateratzeko, baina justu beheko kantinatik gora guardia zibilak heldu ziren eta nirekin zihoazenei “alto” esan, paketeak bota eta ihes egin zuten. Baina nik ezin nuen eskapatu bi paketeekin, eta goitik behera nindoala bertzeek utzitako pakete bat ikusi eta hartu egin nuen arrastaka, eta orduan egin zidaten tiro. Han geratu nintzen kieto, gero guardia zibilak etorri eta “cállate y no declares nada” erran zidaten eta paketeak hartu eta han utzi ninduten. Hotza sentitzen hasi nintzen, eta gainera, tiroketa bat entzun nuen ordubetera eta beldur nintzen nire koadrilakoei tiro egin ote zieten. Azkenean, anaia auzokoekin etorri zen bila eta bizkarrean eraman ninduen etxera. Hortik ospitalera, eta ondotik, Iruñeko Opusera. Hiru hilabete eman nituen han. Ordutik, mendia utzi behar izan nuen eta autoarekin-eta ibili nintzen kontrabandoan.

Eta gainontzean, noizbait harrapatu zintuzten kontrabandoan ari zinela?

Bai, errodamenduak pasatzen ari nintzela atzeman ninduten; momentuan autoa kendu eta preso eraman ninduten Iruñera. Ez zen normala izaten, baina hala gertatu zen. Libre ateratzeko eta autoa berreskuratzeko ordaindu nuen, eta errodamenduak itzuli zizkidaten.

Apolo astoa bazkide ona omen zenuten.

Lan asko egin zuen horrek! Garai horretan Apolo espaziontzia ilargira bidali zuten, eta hortik datorkio izena. Mandoak bidea ezagutzen zuenez, kargatzen genuen eta bera bakarrik joaten zen. Guardia zibilak azkarrak izan balira erraza izango zuketen gu zein ginen jakitea, mandoari jarraitu eta kito, baina ez ziren horren azkarrak, beharrik! Apolok hamabost pakete ekartzen zituen, eta hortaz, hamabost lagunen lana berak bakarrik egiten zuen. Gero saria pentsua izaten zuen.

Gaur egun aukera izanda, kontrabandoan segituko zenuke?

Muga balitz, zergatik ez?

BRN + Neighborhood and Sain Mountain + Odei + Monsieur le crepe and Muxker

What: The harvest party.

When: May 2nd.

In which: In the Bilborock Room.

---------------------------------------------------------

The seeds sown need water, light and time to germinate. Nature has... [+]