130 years of accident history

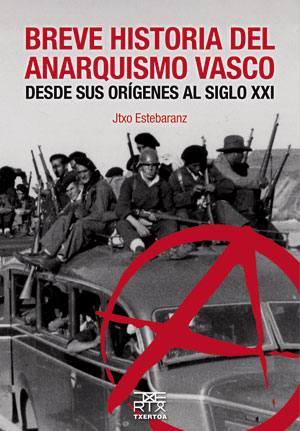

- Juantxo Estebaranze analyzes in his last book the characters and controversies that led the Basque anarchist movement: Brief history of Basque anarchism (Txertoa 2011). We have made a review of this story, with the help of the author himself.

In the last third of the nineteenth century, some praxis and theories proposed in France gave rise to a political tendency known as anarchism. Unlike the socialist groups born in 1864 in the International Workers Association, anarchists rejected the resources of formal policy. They prioritized direct action and general strike, emphasizing the prominence of the rebels themselves and setting aside intermediaries of all kinds. The first anarchist groups, supporting each other, sought to satisfy the needs of the proletariat born with the Industrial Revolution. “That first anarchism was that of the International, whose axis was mutual aid. Over the years, these groups made up of artisans and artisans would have incorporated into the new factories’ workforce,” explains historian Juantxo Estebaranz.

The Basques played from the outset both in the International and in the Regional Federation of Spain, of which it was its branch (1870). However, the anarchist groups of Zumarraga, Bilbao, Vitoria-Gasteiz, Tolosa, Irun and Pamplona/Iruña did not have much influence on the working class that was created in the mines of Bizkaia: “The miners did not have a tradition of organization that the anarchists had and dominated the syndicalist model of the socialists,” says Estebarn. With the splendor of the Paris Commune and the illegalization of the International, the beginning of the twentieth century witnessed the new tendencies of the labor movement. It was the turn of the big anarchist unions. Under the influence of union action, they wanted to build a large organization, with this intention they approached the new working class and all the trends that were not organized. In 1910 the National Confederation of Labor (CNT) was born and in the first assembly of 1911 groups from Bilbao and Barakaldo participated.

Different realities of Euskal Herria

In the Basque Country, the Single Union would be the main characteristic of anarchists. It brought together the workers of all trades in the local federations. In Vitoria-Gasteiz, Pamplona or Tolosa, the Single Union had a lot of strength, causing fear and repression among the powerful classes. “The reality of Basque Country was not one and the only one. In Bizkaia there were mine workers, in Gipuzkoa and Sakana the small processing industries dominated, and in the Ribera and La Rioja there were day laborers, as well as aid associations working against communal property. The different economic situation, the structuring of property and the administrative divisions of each territory make it difficult to give a joint vision of Basque anarchism”, explains the historian.

Dictatorships, repression and bans will condition the trajectory of anarchism. The tension between the tendencies within her, on the one hand trade unionist, on the other hand, by direct action, was accentuated in times of weakness: “After several failures, they repeatedly questioned the role of anarchosyndicalism, because some prefer direct action, punitive actions.” Permitting and intrantsiveness are, therefore, two sides of anarchism, always present. It could be said, simplifying, that today they are reflected in CNT-AIT and CGT. But they were not the only tasks of Basque anarchism: “In the 1930s, after the end of Primo’s dictatorship, new generations who knew of free culture experiences will approach the CNT. For anarchists, the contribution of culture has always been important, since the intention to improve the human condition through culture has always been at the basis of anarchism. Rationalism, free schools, publications, newspapers, toilets are also indispensable elements of anarchism. Isaac Puente or the Chiapusotarrak are the exponents of this tradition,” explains Estebarn.

The Force of Anarchism in the Basque Country

In the 1970s, the CNT had a great force in Catalonia, Valencia or Madrid. In the Basque Country, however, the situation was different. According to the historian, “once the prohibitions are over, the CNT has always had a great capacity to rebuild the institution. However, after Franco's death, it seems that they went back; that is, although the times changed, the experience of the 1930s was too heavy; mimetically they sought to avoid the conciliation instruments developed in the working world during the dictatorship and the transition, such as the works councils. In addition, since 1968 the assembly movement was extended by Euskal Herria and a block in favor of fracture began to appear, which was replaced by the CNT in the rest of the Spanish State. At that time, the movement for rupture, which included the revolutionary Abertzales, avoided formal politics.”

According to the author of the book Brief history of Basque anarchism, the Basque tendencies defended by the Askatasuna collective within the CNT had not had enough repercussions and some decided to work outside this institution: “They started working from the human movements, without putting an anarchist of surnames on what they did. Today, the situation is similar: the rupturistic movement that we have mentioned before looks with good eyes at the institutional pathways and there are still those who have the axis of the assembly. Now, the proposals are clearer and the anti-authoritarian space is willing to recover the fracturers that previously also received other movements”.

Bilbotik Meatzalderantz joanez gero, lehenengo Barakaldo herriarekin egingo dugu topo. Merkatalgune erraldoiek edota Bilbao Exhibition Centrek, besteak beste, betetzen dituzte gaur egun bertako lurrak. XIII. mendera arte, berriz, nekazaritzatik bizi ziren barakaldarrak... [+]

Bizkaian badira bi lurralde (bakarra ote?) beste guztiek baino askoz ezezagunagoak eta baztertuagoak daudenak: Enkarterria... [+]

Jon Torner jontorner@argia.eus

1889az geroztik, maiatzaren 1ean munduko langileria kalera atera ohi da bere aldarrikapenak entzunarazteko. Urte hartan II. Internazionalak egun hau Langileen Nazioarteko Eguna izendatu zuen eta urtez urte, maiatzaren lehena iristean... [+]