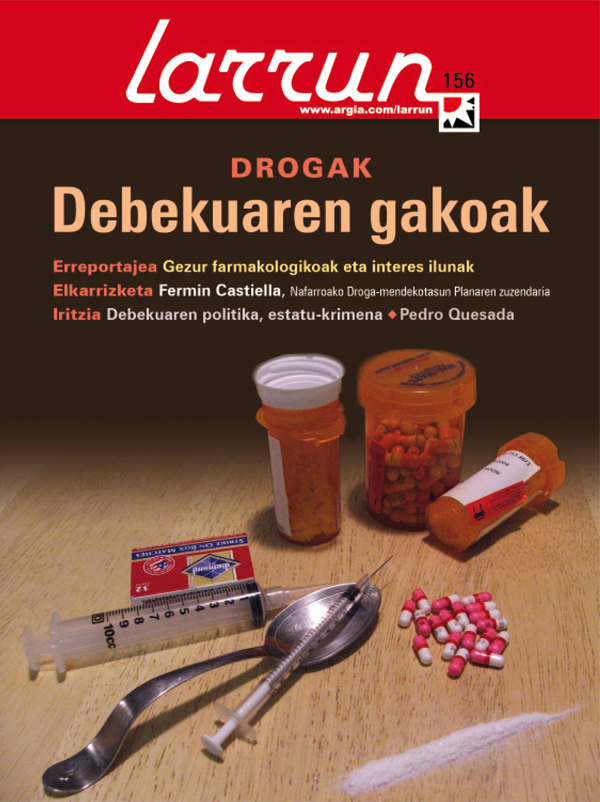

Pharmacological lies and dark interests

- Human beings have been using drugs for thousands of years and the attitude of the authorities has not always been the same. Throughout history, all the drugs we know, including tobacco and coffee, have been banned at some point and somewhere; but surely the time we are living is the most prohibitive. Much has already been said about the consequences of this, such as the advantages or disadvantages that the elimination of all prohibitions would entail. In the next report we will analyze the origin and development of these policies, especially from the work of the thinker Antonio Escohotado. In the end, we will also talk about the forces that maintain the ban. The illegalization of many psychoactive substances has been much worse than the problem that was intended to be solved, however, the ignorance about drugs and the benefits that some derive from this status quo greatly hinder the return to the situation.

In May 2009, in issue number 2.182 of Argia, we inform you of a report published by the British Policy Foundation Association, Transform Drug. Using concrete figures, the report showed that the legalisation of all drugs, in addition to the benefits that are clearly visible – reducing crime, avoiding thousands of arrests and detentions, the disappearance of street-poisoned substitutes… – also from an economic point of view would favour the State. That is how the Transform Drug Policy Foundation responded shortly before to the London Government, which, although some advantages of legalization are undisputed, the expenditure it would entail would be excessive and therefore would not be promoted, either at home or internationally. The government officials, however, did not put on the table the numbers that justified their assertion, as reported by the Generalitat.

That report is no more than an example. Various independent studies have been carried out in the analysis of the consequences of drug policy in recent decades, and they have drawn the same conclusion: the strategy of excluding certain substances has not met its objective, but the opposite is the increase in consumption, rather than reducing it, and, in addition, the prohibition has created other problems.

The problem didn't exist a century ago.

Spanish author Antonio Escohotado goes further: prohibition creates a problem where there was no problem before. From the hand of the Madrilenian is one of the most complete, precise and certainly most forceful works ever written on drugs: General History of Drugs (General History of Drugs) Among many other things, points out that at the beginning of the twentieth century, when all drugs known at that time – much less than today – could be freely bought in pharmacies, their consumption was not the social evil that needed the solution. There was no problem, with capitals, and if so, some users, not too many, would have an inadequate relationship with the drug. “There is no doubt that there were subjects to opium, morphine and heroin, but that the phenomenon as a whole, that is, the sum of those who consumed moderately or excessively, rarely reached the attention of the media, and never that of judges and police. Drugs were not a legal, political or social ethical issue”.

However, there was always, according to Escohotado, who at that time protested about the situation. It can be said that it was then that the process began to take place decades later with the current ban. Pharmacological crusade, called the Madrilenian.

These groups gained more and more strength in the United States. Their main characteristic was puritanism, and they saw with bad eyes the use of psychoactive substances, for which more than vice was crime and contagious disease. The phenomenon is related to the racist, xenophobic and fundamentalist attitudes of these groups. Thus, each drug was associated with a particular group: the first social alarm about opium was triggered in the context of the corruption of minors charged to the Chinese; cocaine, in relation to the crimes attributed to blacks; marijuana, with the appearance of waves of Mexican immigrants; alcohol, with the alleged immorality of Irish and Jewish.

Interestingly, other psychoactive substances, much more toxic than those mentioned, such as barbiturates, were not linked to any group and, free from stigma, would be outside the prohibition that would apply in the future.

The Anti-Saloon League was founded in 1895 in the United States, an association that soon brought millions of members together. “America cleans from drunkenness, from play and from the sin of flesh,” was the goal they sought. As for drugs, the group was initially limited to acting against alcohol, but soon they also started against the other substances. The reason was that the Puritans found a travel companion: societies of doctors and pharmacists, who since the late nineteenth century were immersed in the war against herbalists and petricilos to get control of drugs.

The alliance between the two groups materialized in 1903. The following points are set out: “He who gives a drug that has not been sold in one pharmacy to another, destroys his soul”; “morphine is a devil, but it can become a blessing if it is distributed by qualified therapists.”

Drug recipients, “brave” citizens

In 1905, when opium and morphine were among the best-selling drugs in the United States, some of these groups said that the free sale of these substances would make prostitute children and girls criminal. But that prophecy had to wait for the total ban to be complied with. Meanwhile, and this would continue to be the case for decades, most of these two drugs and the usual heroin recipients were mature and elderly citizens, who exercised their professions and other social functions without any problem, according to Escohotado.

In Europe, on the other hand, the situation was similar, but much less was said about it. Consuming or not using drugs was the same as going to the theater or eating too much or too little fish, just a personal choice. In spite of everything, from time to time the media were concerned about this news. The Valencian historian and sociologist Juan Carlos Usó has done an intense work of analysis of the history of drugs, always within the Spanish State, and has told us about that time: “XIX. From the end of the century, Spanish newspapers occasionally commented on the huge consumption of morphine in Paris or on the success of ether among the most marginalised citizens in Ireland. Examples from Spain were never mentioned. It is curious, on the other hand, that one of the biggest concerns was the excessive use of ether, substances that do not appear on today’s playful drug lists.”

In any case, these are substances that could be bought in pharmacies with complete freedom, as Usó has pointed out. “The effects of these drugs and their therapeutic applications were well known; what raised concern and perplexity was that some people took them for non-therapeutic purposes.”

Not all the prohibitors were right-wing.

Although the reaction against drugs was initiated by U.S. puritanism, Usó does not believe that his prohibitive thesis would eventually prevail around the world as a triumph of conservative thinking, “perhaps the very opposite”. By way of example, he recalled the first two daily newspapers that led the campaign against drugs in the Spanish State: “Two newspapers in Barcelona urged the government to do something to stop the spread of recreational cocaine use, which was done in 1915, when cocaine was still sold in pharmacies, in 1917. Well, both were leftist publications, especially Germinal, who defined himself as a radical Republican”. According to Usó, some authors believe that the United States managed to extend its crusade to the whole world because at that time it was considered a modern policy, not a conservative one. “The conservative, at that time, was to let people do what they wanted, and the state intervene, progressive.” This intervention, in principle, was not a total ban, but a limitation of consumption.

First international conventions

In the United States, the trio of puritan-medical-pharmacists finally managed to make their wishes laws: The Harrison Law was approved in 1914. From now on, the use of opium, morphine, heroin and cocaine without a prescription would be banned. At the same time, in other countries around the world, American theses began to be disseminated. That is, the “pharmacological diet”, using the words of Escohotado, was something that had to regulate the state. In the Hague Conventions (1912, 1913 and 1914), eight countries agreed on something similar to the Harrison Law, but not so hard. Among other things, they allowed the free sale of the above-mentioned drugs, except heroin, which contained small quantities of compounds. Despite the fact that the United States could be considered victors of the Conventions, the United States delegation did not welcome such blunt measures. They would be more happy when, in 1919, in the small letter of the Treaty of Versailles, the Hague Conventions were incorporated and almost all the countries of the world adopted them.

However, the United States wanted more and convened another international conference in 1925 in Geneva, but they left before it was over, angry. The agreements of that time did not bring about major novelties compared to those of a decade ago. On the one hand, heroin and cannabis were added to the list of substances to be controlled. On the other hand, the signatories undertook not to export controlled drugs to countries where they were banned (at that time the United States was the only country in the world at that time) and to decide on the creation of laws against illicit trafficking. The only sanction provided for the confiscation of the substance.

These soft measures were taken as a mockery by the Americans, but, according to Escohotado, they coincided with the situation in the other countries: “The Spanish case – which was in The Hague and in Geneva – demonstrates this: Between 1920 and 1930, when opium, morphine and prescription and over-the-counter cocaine were administered in local pharmacies, only six people died from overdoses of these drugs, five of them from suicide.” However, the adoption of the Geneva Convention meant the creation of a black market for low-purity drugs, as ten years ago in the United States.

Six years later, and again in Geneva, what Escohotado defines as “the first victory of the prohibitive spirit” happened: The Standing Committee of the Convention, created in 1925, was given the power to fight drug addiction. “This laid the groundwork for creating a complex network of international organizations that, over time, would have thousands of officials.” Finally, in 1936, criminal measures were imposed, also in Geneva and H.S. Under the direction of Anslinsger. Anslinger was one of the agents involved in complying with the Seca Law suspended three years ago, a momentous character in the history of drug prohibition. In the third Geneva agreement, all states were able to create specialized police services. It also made it possible for all the signatories to commit themselves to punishing both drug trafficking and property imprisonment.

Meanwhile, the United States maintained its tightening of domestic legislation for the following years. In 1956, the Narcotics Control Act was enacted, a law that tightened the penalty for selling or holding heroin. That year, in American jails there were barely 1,000 prisoners for possession of heroin; half were black, Mexican and Puerto Rican. The long-term consumer – white, over 40 years old, with a respectable position in society – found, through repression, a substitute for other (legal) drugs. This was favored by the wave of new substances discovered or synthesized from the 1930s onwards. Many of these substances made a long journey through pharmacies freely, until the dangers, or even more, of those prohibited were apparent. So they brought them to the list of the ones they had to control.

Four years after the entry into force of the Narcotics Control Act, the number of people imprisoned for heroin possession had reached 10,000 and organizations estimated that there were another 50,000 on the street.

Justifying the ban on the back of science

Addictive drugs had not yet been defined. The World Health Organization had an Expert Committee on this type of substance, which in 1953 stated that this type of drug produced the sum of habits, tolerance and physical dependence. “However,” says Antonio Escohotado, “cannabis and cocaine could not be included in that definition, nor could alcohol, barbiturates and many others be left out.” Driven by drug protests and many others, experts “updated” the definition in 1957, saying that banned drugs generate addiction; those that are not banned, just custom.

This distinction had nothing to do with serious pharmacology, and the protests did not remain silent, quite the opposite. “Tired of trying to define the prohibitive, he already had in his hands a list of prohibited substances [Escohotado speaks of 1963], the secretary of the Committee of Experts pointed out that “it was impossible to establish a correlation between data from biology and administrative measures.” Finally, the experts proposed replacing the terms “addiction” and “habit” with “submission”.

Lost in the fog of lack of information

The drugs policy of the last five decades has been characterized by legislations that have nothing to do with “the data of biology”. We can say that this is the time of total prohibition. I mean. But in the early years, the size of the problem was small. According to the calculation quoted by Escohotado, in 1960, “200,000 civilized citizens took opium, heroin, cocaine and cannabis in the United States and Europe; a small, compared to hundreds of millions of inhabitants”. A year later, in New York, the Joint Agreement on Drugs, the main basis of current international legislation, was signed.

Despite the prohibitions, laboratories continued to produce legal alternatives, and pharmacies around the world were full of all kinds of drugs. The number of people who used to consume a product there was eight or ten times that of the non-prohibited time, but many of them did not even believe they were dependent on a psychoactive drug. This situation remains the same at present: to give just one example, benzodiazepines and other tranquilizers are sold per tonne in exchange for a simple recipe and very little money. Many of these substances suffer much more damage to health than opium derivatives if they are taken for a long time, and their withdrawal syndromes, although incredible for the smaller citizen, are much more dangerous than heroin. You can say the same thing about alcohol, by the way. Its recipients, however, do not bear the burden of the “drug addict” stigma on their backs.

The Mafias circulating in the black market, for their part, flourished with the ban, which made the above mentioned ones more than 200,000 before the end of the 1970s. In 1972, the U.S. Attorney General set the alarm on: “In 1961 we had about 50,000 heroin addicts. Today we think it’s 560,000.” There was a similar leap in Europe, but a decade later.

The myth of heroin overdose

Those heroin addicts did not trust the quality of the drug too much. Those who died supposedly from overdose became symbols of the 1970s and 1980s. Escohotado remembers that it is not very reasonable to think that he has died by putting in his veins a heroin that has 10% purity at most, that he has died from overdose, but in the statistics that were officially introduced thousands of bodies were found with a syringe hanging from his arms. Another pharmacological lie. Any derivative of opium, if you're overdosed to death, will take several hours, not a few minutes. However, the deaths in this way stopped promoting social alarm a long time ago, as their number has dropped dramatically over the last two decades. Another argument that proves, for Escohotado, that in terms of drugs citizens know how to go about themselves, without the protection of the State.

Economic interests, the main obstacle to legislative change

The terrible consequences of the illegal use of certain drugs are well known. We have also seen that the classification that has led some substances to the common store, others to the pharmacy and the rest to the criminal environments is not consistent with pharmacology. Why, then, is international legislation maintained that has not only failed so clearly, but has created new problems?

Although seemingly unfounded, mere inertia can be one of the reasons, at least for Juan Carlos Usó. The moral reasons defended a century ago by the first prohibitionists also remain there in part. Ignorance about the consequences of drugs also helps; it is difficult to convince someone who remembers well in the 1980s that heroin is not a malicious substance in itself, and that it can be used and used appropriately by thousands of anonymous citizens. It is not easy to give accurate data, because it is only visible when the use of the drug is associated with problems. Serve this example: The result of a survey conducted in the United States in the 1970s surprised the U.S. president. Two million Americans said they had taken a heroin last week, four times more than the worst estimate police had ever done in recent days. This unraveled the official version that no one was able to control themselves with a drug like heroin. In fact, in 1972 only 0.18% of consumers asked to recover from their addiction to breast milk.

However, it can be said without fear that the main reason for prohibited policies to be maintained is the businesses that have flourished as a result of them. In the words of Koldo Callado, professor of the Department of Pharmacology at UPV/EHU, “all the interests that underpin the ban will not be economic, but if they did not exist it would be much easier to normalize all this”. For Callado it is very difficult to understand that tobacco is legal and cannabis is not, “without thinking that the factual powers behind the governments of the world divide the business.” To this must be added the hundreds of organizations and groups working on risk prevention, the rehabilitation of adiktos, substance control or simply harassment. Too much organization to disassemble from one day to the next.

In many European countries, steps have, de facto, been taken towards the normalisation referred to by Callado. The departure of a country from international treaties seems more difficult, as that, among other things, would lead to strong pressure in the United States. However, it has been shown that, without violating the agreements, more reasonable policies can be put in place than those of the Americans. So risk reduction is the philosophy that has prevailed in many countries in Europe. This does not prevent more than half of the prison tenants from being small drug dealers – large, almost none – but they give a little encouragement to the consumer. In some states, consumption and ownership have gone unpunished, which has not brought with it the catastrophic situation announced by some. In this regard, in the Netherlands, the most liberal country in Europe, for example, the percentage of receptive cannabis is lower than that of all the countries around it. The ban has led to an increase in the consumption of what is prohibited, at least in problematic consumption.

“The emergence of drug use as a disease and crime became the largest business of the 20th century,” says Escohotado. “A business that needs to last, not to separate drugs for their concrete consequences, but for their legal status.” After the arbitrary classification, the Spanish author sees the logic of two markets, white and black. “Of the products on the white market, very few would be successful underground. But with the most desirable drugs on the black market, sellers of authorised and prohibited substitutes get huge profits.” More and more voices are calling for a radical change in current drug policies, but they do not have an easy job: they face too strong forces.

Substantzia psikoaktiboen alderdi txar guztien ikur nagusi heroina bilakarazi zutenez gero, ez da harritzekoa junkiaren figura erabili izana drogara “hurbiltzeak” dituen arriskuen eredu. Escohotadok 50eko hamarkadan kokatzen du junkien agerpena, AEBetan nola ez. Debekuak sortutako pertsonajea da, ordura arte ezezaguna. “Lehen, opioaren eratorriak hartzera ohituta zeudenak beren eguneroko eginkizunak hobeto betetzeko energia iturri modura hartzen zuten droga. Kontsumitzaile mota berri honek guztiz aurkakoa bilatzen zuen: hartzaile tradizionalek baino askoz droga kopuru txikiagoak hartu arren, ez zuen helburutzat bere ardurak hobeto betetzea, bere burua arduragabe izendatzea baino”. Junkia ezaugarri bik definitzen dute, Escohotadoren iritziz: xiringaren erritualarekiko atxikimendua eta biktima rola jokatzea. “Bestalde, ez dauka zentzu handirik pentsatzeak hartzen duten dena delako horren %5 bakarrik heroina izanda, benetako heroinomanoak direnik”. Horren arabera, junkiak bere drama antzeztu nahi du, bizitzak ezarritako beteharretatik ihesi, eta xiringaren askoz behar handiagoa dauka xiringa barruan dagoenarena baino. Droga hartzen hasi aurretik, eta ez drogaren erruz, arazoak zituen pertsona da. Beste era batera esanda: heroina kontsumitzeak ez zaramatza ezinbestean junkia izatera, hori izan arren uste zabalduena.

Vagina Shadow(iko)

Group: The Mud Flowers.

The actors: Araitz Katarain, Janire Arrizabalaga and Izaro Bilbao.

Directed by: by Iraitz Lizarraga.

When: February 2nd.

In which: In the Usurbil Fire Room.