Metamorphosis of the Abertzale syndicate

- In July 1911, the Solidarity of Basque Workers was founded, today known as Euskal Langileen Alkartasuna (ELA). The union that emerged within the ideas of Sabino Arana preached dialogue between social classes and deplored socialism. Now, on the other hand, it is at the forefront of the labour struggle and has endorsed the ideas of the left. What has happened within the Abertzale trade union in these hundred years?

Solidarity of Basque Workers was structured in Bilbao 100 years ago. The 178 workers signed up to take the step of forming part of the new partnership. That same year, while the anarchist union CNT failed its first steps in Barcelona, the Biscayan people came together to defend the rights of the working class from very different perspectives. Like the UGT trade union, which has been established in Bizkaia for several years, they had a political organization: The Socialist Party was UGT and the Basque Nationalist Party was SOV.

Since Sabino Arana himself considered it appropriate to bring together Basque workers, a committee was formed from time to time within the Social Democratic Party to deal with the social question. When the Nationalist Party started taking the first political steps, the stage was very hot, because of a social problem. From 1890 onwards, the continuous strikes and mobilizations of the miners and the workers of the Left Bank of the Nervión led to the socialization of the old demands of the new proletariat. These conflicts claimed the improvement of living conditions and work activities, but behind them, the brothers Facundo Perezagua, Carretero and others began to successfully spread the socialist conception.

For social dialogue, against socialism

In this context, the Solidarity of Basque Workers was launched by the Abertzales dealing with the social question. It was for the natives, because those who wanted to be asked to have at least one Basque surname in the rules of origin. In the same way, the Church proclaimed by holding the encyclical Rerum Novarum that they intended to serve among the working class, but without promoting the struggle between the classes. According to the solidarity groups, dialogue between the classes had to put an end to the clashes between the bourgeoisie and the workers. In order to deal with the new ideology, socialism, they thought it appropriate to promote co-ownership through cooperatives, but in no case to question the funds of capitalism. In this regard, ELA promoted initiatives in favour of cooperativism and mutualism. Instead of drawing attention to strikes and mobilizations, the union prioritized dealing with the situations of unemployment or extortion suffered by its partners. Thus, in 1919 unemployment insurance was launched and in that same year the first cooperative was created.

With these origins and fundamentals, ELA spread during the first decades in the shadow of the Basque Nationalist Party. In Bizkaia and Gipuzkoa, the expansion was rapid, but in Álava and Navarre it was more difficult than in any other territory. The first congress of the union took place in Eibar in 1929, with 6,200 Biscayan partners and 1,500 Gipuzkoans represented, but there was no outstanding representation in the rest of the territories. On the one hand, the lack of industrialization that existed in Álava and Navarre significantly limited the human sphere of all trade unions. On the other hand, in the rural area, especially in Navarra, the initiative promoted by the Church itself (Rural Boxes, Culture Processing Cooperatives, Leisure Txokos..) already had the moderate space that ELA could sympathize with.

II. Republic: Workers' Solidarity

However, the II Durango Fair ended Marfa Strogoff's life. ELA, like the other trade unions, achieved a huge expansion with the Republic. After the enactment of the new regime, the solidarity forces were consolidated in Bizkaia and Gipuzkoa, and also rooted in Álava and Navarre. In the first months, the political hegemony of the leftist parties acculturated the propaganda and constituent initiatives of the Abertzale union. José Ariztimuño Aitzol wrote an article in the press, on the occasion of the left victory in the first elections: The workers leave us with a significant title and we have a direct reflection of that concern. Specifically, Aitzol itself, Policarpo Larrañaga, Nestor Zubeldia, and above all, Manu Robles Arangiz, Jose Benegas, Welcome Cilveti (see interview on page 9) and Anastasi Agerre were in charge of disseminating the ELA message throughout the Basque Country. The number of partners in the coming years was a certain success. In fact, when the second assembly was held in Vitoria-Gasteiz in 1933, the union had 40,342 members, which constituted 135 groups. Of the total number of deaths, 63 were Biscayan, 52 Gipuzkoans, 12 Alaveses and 8 Navarros, among others. In addition, sectors that had previously remained outside the trade union (fishermen, farmers and liberal professions) also had the opportunity to participate in the trade union. To better reflect this widest possible reality, the name of SOV was omitted and became Solidarity of Basque Workers.

As for trade union praxis, this congress in Vitoria-Gasteiz gave the usual importance to the health care sectors, but the difficult socio-economic situation of the time also had to be addressed. Without forgetting the dreams and cooperative initiatives, they had to take action on several occasions against strikes and mobilisations driven by workers and other institutions. The “human peace”, extended by unions such as UGT and CNT in the first biennium of the Republic to the Government of Spain and to local employers, was about to end. In the industrial sphere, unemployment was increasing and land reform was still not going back. What happened with the October 1934 strike was significant. STV stood against, but many of its members joined this mobilization that wanted to be general and revolutionary. In 1936, when the victory of the Popular Front came, the Solidarity Workers joined a great deal with the vindictive flood. In Navarre, for example, the first general strike in the construction sector took place in June of the same year between STV and UGT workers.

Civil war: death, imprisonment and exile

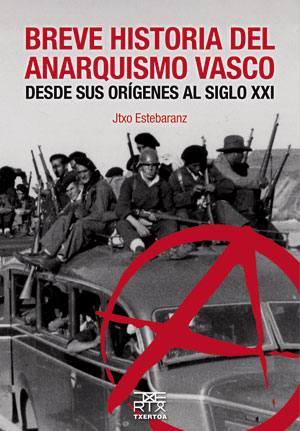

The definitive rapprochement to these leftist unions was brought about by the War of 1936, where it was possible, that is, in Gipuzkoa and especially in Bizkaia. Many of the solidarity workers in these regions joined leftist parties and institutions to deal with the fascist insurgents. The ALS formed the San Andres battalion, but they also participated in many others. In Santoña, after the surrender of the Basque Army, in the first collective shooting – among the victims chosen by the Franco were all the anti-fascist associations – the ALS paid the blood tax with the murders of Jesús Zabala and José Ibarbia. From July 1936, like all democrats, the Rainbow colleagues fought for Heaven. But also, from then on his fate was death, jail and exile. They could be right-wing and Catholic, but fighting for the workers and being Basque was entering the group of Gorriseparatists. For this reason, during the Franco dictatorship ELA had to act from exile and secrecy. The war prevented them from reaching the Third World War in July 1936. The holding of this congress in Pamplona was not possible until 1976.

During this time, in addition to participating in the initiatives carried out abroad (the Baiona Convention in 1945, the Basque World Congress in Paris in 1956, the Munich Plenary Session in 1962...), the ELA strikes were directly affected both in 1947 and in 1951. However, as the late 1960s and the end of the Franco dictatorship strengthened within the working class other institutions and movements, the historic unions such as ELA had an increasingly low echo.

After 40 years of ice, fighting time

In the case of Basque solidarity, the internal divisions and the consequent creation of different groups – ELA-Biarritz or historical; ELA internal... – made their political and trade union activity difficult. In fact, ELA had a very special starting point in the post-Franco transition. CCOO, then the stronger workers' organization, was prepared to approach the Portuguese model, that is, the option of a single trade union. This would mean the dissolution of all trade unions into a single organization. On the other hand, from the watchtower of ideology, ALS was totally different from ALS back then, when compared to the original. His ideological slavery with the PNV in the first decades and the intervention of numerous political leaders – Manu Robles, Heliodoro de la Torre… – was over, although it remained Abertzale. On the contrary, the union created at the beginning of the century to deal with socialism had completely internalized that ideology in the 1960s, socialism was in its strategic political line. Also in this case, the new associations such as USO, which emerged in times of UGT and Franco, were going to compete. But at the level of praxis, ELA was willing to face the struggle between classes, and UGT, for the sake of pacts, would immediately re-entrench the fighting positions. In addition to promoting all the resistance funds and traditional relief guarantees, ELA turned to its strategy against the pacts and to the mobilizations against industrial restructuring in the Basque Country.

Today, when the political transition moves away and the economic context is very different, we have enough scope to take stock. In this sense, it is noted that the majority unions in the whole of Spain, UGT and CCOO, in Hego Euskal Herria, have lagged behind ELA in terms of partners and trade union representatives. In addition, given the growth experienced by LAB and some sectoral unions, such as STEE-EILAS, in recent decades, it is clear that the Basque trade union area is very different from the one in Spain a.Como it is known,

CCOO and UGT have signed two agreements with the State governments and with the employers' associations (CEOE) or Bask. On the contrary, they have faced unions such as ELA. From the Moncloa Pacts to the latest Labour and Pension Reforms, the trade union majority of ELA, LAB, STEE-EILAS, HIRU and EHNE have shown much greater value for strike and mobilizations, and have made it clear that the ideas and praxis of the early twentieth century have changed radically. Some who claimed the struggle between the classes say that today it suffices with the remains that the bourgeoisie offers it. On the contrary, those who promoted friendship between classes, through experience and history, have internalized that as long as capitalism is in force, only thanks to the courage of the workers can progress in the defense of their dignity.

Bilbotik Meatzalderantz joanez gero, lehenengo Barakaldo herriarekin egingo dugu topo. Merkatalgune erraldoiek edota Bilbao Exhibition Centrek, besteak beste, betetzen dituzte gaur egun bertako lurrak. XIII. mendera arte, berriz, nekazaritzatik bizi ziren barakaldarrak... [+]

Bizkaian badira bi lurralde (bakarra ote?) beste guztiek baino askoz ezezagunagoak eta baztertuagoak daudenak: Enkarterria... [+]

Jon Torner jontorner@argia.eus

1889az geroztik, maiatzaren 1ean munduko langileria kalera atera ohi da bere aldarrikapenak entzunarazteko. Urte hartan II. Internazionalak egun hau Langileen Nazioarteko Eguna izendatu zuen eta urtez urte, maiatzaren lehena iristean... [+]