Luminous movements 2.0

- The revolutions of the Arab countries and the camps of the angry have been some of the most recent examples. Leveraging the diffusion capacity of the Internet and the momentum of social networks such as Twitter and Facebook, new technologies have succeeded in activating people with a desire for change. However, not all opinions on the effectiveness of cyber-movements are optimistic.

The biggest protest in Moldavia's history was rated by The New York Times as "the Twitter revolution." Following the message disseminated through the social network, on 5 April 2009, 20,000 people gathered in the capital to denounce the corrupt elections that same day. The votes achieved a new scrutiny. A year later, the media also said that demonstrations in Iran in protest at the manipulation of the election results also had to do with Twitter. However, the critical voices were soon to take the floor: the social network has very few users in Moldova, and so does Iran. Those who wished to undermine the impact of new technologies argued, for example, that Twitter has fewer than 10,000 users in Iran and that most messages were sent in English and not in Farsi, i.e. mainly from abroad and not from the country itself.

After a few months, the Arab world broke out: The path taken by Tunisia was followed by other countries in the uprisings against the Heads of Government. Once again, the debate focused on the role of technology in all of this, and one of the clearest expressions of the strength of the Network is the attitude of those in power: For the first time in the history of the Internet, the then Egyptian president, Hosni Mubarak, interrupted the access to the Internet of the inhabitants of a whole state and the possibility of using the SMS service. This behavior can only be understood by the fear of the ability of technology to maintain, extend and strengthen the rebellion. Aware of this capacity, the Egyptians sought alternatives such as the use of landlines, fax, radio, non-Internet (dial-up) modems or the only server that continued to function (Noor) with anonymous software to not be intercepted by the authorities.

In the other Arab countries where the uprisings took place, technology also suffered cuts by the powerful. According to a report by the association Reporters without Borders, last year they were censored on the Internet in 62 countries. “Authoritarian regimes have learned to use these tools, and the fact that there are more and cheaper tools in the wrong hands means nothing but less democracy,” said Russian blogger Evgeny Morozov in his book The Net Desilusion. After all, we cannot forget that, as a result of the above-mentioned demonstrations in Iran, the Government used technology to monitor and control dissidents who communicated via social media. In Morozov’s words, “a multicolored internet freedom banner is dangerous, because behind us we can discover that the Internet is much more than a speaker for democratic speeches, which can have totally undemocratic uses and that, if it is not corrected, the goal of promoting democracy may be at risk.” It can facilitate, for example, the repression and total control of the population.

In this regard, American writer and journalist Douglas Rushkoff has warned that the possibilities offered by the Network for subversion should be taken with care: “Yes, services like Twitter and Facebook offer activists the same opportunities as they have never before to organize. But the more they depend on these services, the greater the servitude to the institutions and governments that control these services. We would like to think that we all have a decentralized and limitless connection. But the Internet is fully controlled by the top authorities.” Therefore, Rushkoff says that digital activists have already started to promote new initiatives so that they are not in the hands of service providers, for example, through Wi-Fi some users connect to each other, one after the other. Cyberactivism is a new phenomenon that, faced with obstacles, continues to make its way.

From the Zapatista movement to the M11, Anonymous and Indymedia

Communication is the essence of cyber-movements, the flow of information that allows multi-directional interaction. We have to go to 1994 to find what's known as the first information guerrilla: The Zapatista movement in Chiapas used the electronic network to publicize the objectives of the National Liberation Army (MLNV). The impact that had been obtained had the potential to influence several decisions of the Government of Mexico. In short, behind the success of a movement is the communication capacity, and the communication possibilities of each era (centralized mail system, telegraph, mass media…) have conditioned – allowed – the functioning of the different movements. The Internet promotes communication without centers, without cores acting as intermediaries and leadership in decision-making, based on scattered relationships. The team has strength.

All of this has to be placed in the context of a new generation of social movements. In the second part of the nineteenth century, social movements were especially linked to the class struggle and the control struggle of the nation-state. In the second half of the twentieth century, the so-called New Social Movements will also proliferate: areas such as human rights, racism, freedom of expression, ecology, feminism, antimilitarism, Euskera… will also be a source of claim. The Spanish sociologist Manuel Castells, who has reflected on the subject, says that the Internet movement is characterized by based on values and principles, because the gathering of people around ideas requires a great capacity for communication, and the Internet is a good tool for this. In addition, Castells incorporates two other aspects to cyberactivism: flexible coordination for campaigns and concrete projects in the face of the crisis of organizations, associations and traditional parties of rigid structure; and the global dissemination of local movements. “Glocal awareness – global and local – has been imposed on rights and lawsuits,” says Eduardo A. The Argentine sociologist Vizer. In the network, the discourse of the movements can be constructed in two directions: starting from the needs of a given community, or grouping diverse and heterogeneous groups with universal demands. Paradoxically, global communication has allowed international networks against a globalized neoliberal system.

In spite of everything, we can find very diverse movements related to new technologies. In order to block, hijack or sabotage a website, hacktibism organizes massive shipments of messages and online manifestations (hackerisms driven by political or ideological motivations). The anonymous group, for example, has done a lot of this kind of activity. United States or the Spanish SGAE and various political formations, and have recently threatened to attack government websites and banks for the detention in several countries of members of the group.

Spontaneous concentrations called over the Internet and mobile phone (flashmob, cyberturba, teknoturba…) have become popular. SMS have been key on several occasions: In Seattle EE.UU. In 1999, significant alternating global concentrations of subsequent successions against the World Trade Organization were articulated; mobilizations were instrumental in overthrowing President Joseph Estrada in the Philippines in 2001; with the help of blogs, emails and forums, the cross-messages of the sébastos totaled 4,000 people at the headquarters of pp in Madrid, informed of 11 October 2004.

Several groups base their functioning, organization and project on the Internet, acting as a node or meeting point for activists. Convened by the portal MoveOn.org, in 2003 they held the largest demonstration in New York’s history: 250,000 people face the war in Iraq. Nodo50.org, No Border, Palestinian NGOs Network, World Social Forum, ATTAC, Indymedia that has reached nine years in Euskal Herria… are also speakers of those who want to transform society. Associations that have joined the Internet, of course, have not stayed behind and jumped on the Net; at present, there is no movement without a website. In addition, anyone can be a cyberactivist by creating a blog, uploading videos, spreading messages on social networks… multiplying the echo of speech and attracting people to their cause.

Speed vs. superficial commitment

Yes, new technologies multiply the echo and, although it depends on its use, break with hierarchical pyramid schemes and allow a dynamic organization, which encourages the participation of all members, relating them to anyone in the world. Messages that would otherwise be unthinkable, such as the announcement of the man who eats the finger of an orangutan such as chocolate Kit Kat in the campaign against the Nestlé brand or the information that Wikileaks has suggested, can also be disseminated on the Internet. The Network appears to be a good support to avoid censorship and to denounce injustices.

But what militants get the Internet? It's as easy to forget about the claim as betting on a one-click movement. Against the Facebook incinerator, who has pressed the button of supporting the sick child or boycotting the gas stations – sometimes anonymously – at what level is he aware? Are you really prepared to commit and take real action? According to the article Why the revolution will not be tweeted, published by British writer Malcom Gladwell in The New Yorker, social networks are not able to bring about real social change and have only a “useless commitment” to the causes they defend. On the one hand, interpersonal relationships are superficial, not built by real connections; on the other, because the decentralized structure of the tool does not allow the changes to be effective: “Can you imagine if Martin Luther King had raised his revolution as a debate through Wiki?” The answer has come from a number of fronts: weak ties can become strong links and, furthermore, it would be irresponsible to give up this militancy on the grounds that it is superficial and weak.

However, the saturation of information on the Internet often does not help a reasonable debate. Too many punctual and concrete projects can lead to a dispersed counterbalance, lost on a lot of small fronts and innocuous for the status quo. “People are more likely to express themselves thanks to social media, but it’s harder for that statement to have any impact,” says Gladwell. Therefore, Castells considers that the spaces in which the voices of individuals will be coordinated are necessary to achieve their impact. There should be synergy and support between groups or different movements within the same project. Thus, large virtual pressure groups such as MoveOn.org have been born.

What is the danger? For, precisely, immerse yourself in a self-referential virtual universe that has no reflection in real life, forgetting that the virtual world needs a succession in reality to be effective. Once again, the key is at the level of engagement. It's an interesting initiative that emerged last year on the Facebook social network: The group proposed removing our savings from the bank on 7 December 2010, in order to harm the brutal capitalist system. The initiative received a large number of accessions on the Internet, especially since former French footballer Eric Cantona offered his support in an interview. He even alarmed the British Bankers Association, which warned that a massive outflow of cash from the boxes could cause a disaster. However, when the campaign materialized, real success was not comparable to virtual success, and the response was very small.

In other cases, technological calls have been able to react quickly to warming and to provoke great mobilizations thanks to the snowball effect. It is important that these protests be properly articulated so that they do not lose meaning and do not disappear before they take effect. “Completely spontaneous movements end up disappearing, so it is necessary to correct all this alterglobalizing energy somewhere. We can no longer think that the mere answer of the street is the panacea, nor that the isolated tactics of activism or hacktibism are enough, because the counterpart or microbial can fall into a mere exhibition, in the conformist management of critical and solidarity projects; the alternative power against the official power”, wrote the collective Cibergolem in his work The fifth digital column. That is, in addition to being able to attract new militias and mass protest actions, the planning, concrete and/or comprehensive objectives, the strategies of the future are suitable so that the intentions do not remain in nothing.

By means of

Two conclusions can be drawn from the StopBanque initiative. On the one hand, it seems difficult to achieve real change just by acting in the virtual environment, without taking actions to the streets. Hybrid projects can be the way, taking advantage of the opportunity offered by the Internet to spread the message, awaken those who sleep and rise, but making concrete decisions in the appropriate places. On the other hand, virtual engagement is not synonymous with real engagement. But the Network itself can be a means to engage people in favor of a cause, to make spontaneous concentrations a well-conceived concentration; in short, to what extent is the Internet responsible for superficial militancy and to what extent is it a reflection of current society?

Because things aren't black or white, the cyber-utopian vision isn't realistic, but it doesn't make sense to reject the speaker from the silenced and rejected voices. In any case, Malcom Gladwell is clear: the important thing is not how we protest, but what has pushed us to it.

PuntuEus-ek doako tresna erabilgarri bat jarri du edonoren eskura, webguneen segurtasuna erraz ebaluatzeko. Webtest.eus izeneko autoebaluazio-tresna honi esker, erabiltzaileek beren webgunearen segurtasun-maila modu sinple eta argian azter dezakete.

Zer jakin behar dut? Norekin erlazionatu behar dut? Non bizi behar dut? Ardura horiekin gabiltza gizakiok gure gizarteen baitan bizitza on baten ideia bizitzeko bidean. Ondo erantzuten ez badakigu, bazterretan geratuko garen beldurrez.

Joan den astean, kanpoan geratzearen... [+]

We know that artificial intelligence is representing many fields in human beings: comfort, speed, efficiency ... We've been led to believe that human endeavor is an obstacle to the speed needs of this capitalist world. The aggressions to reduce our chances of doing, doing and... [+]

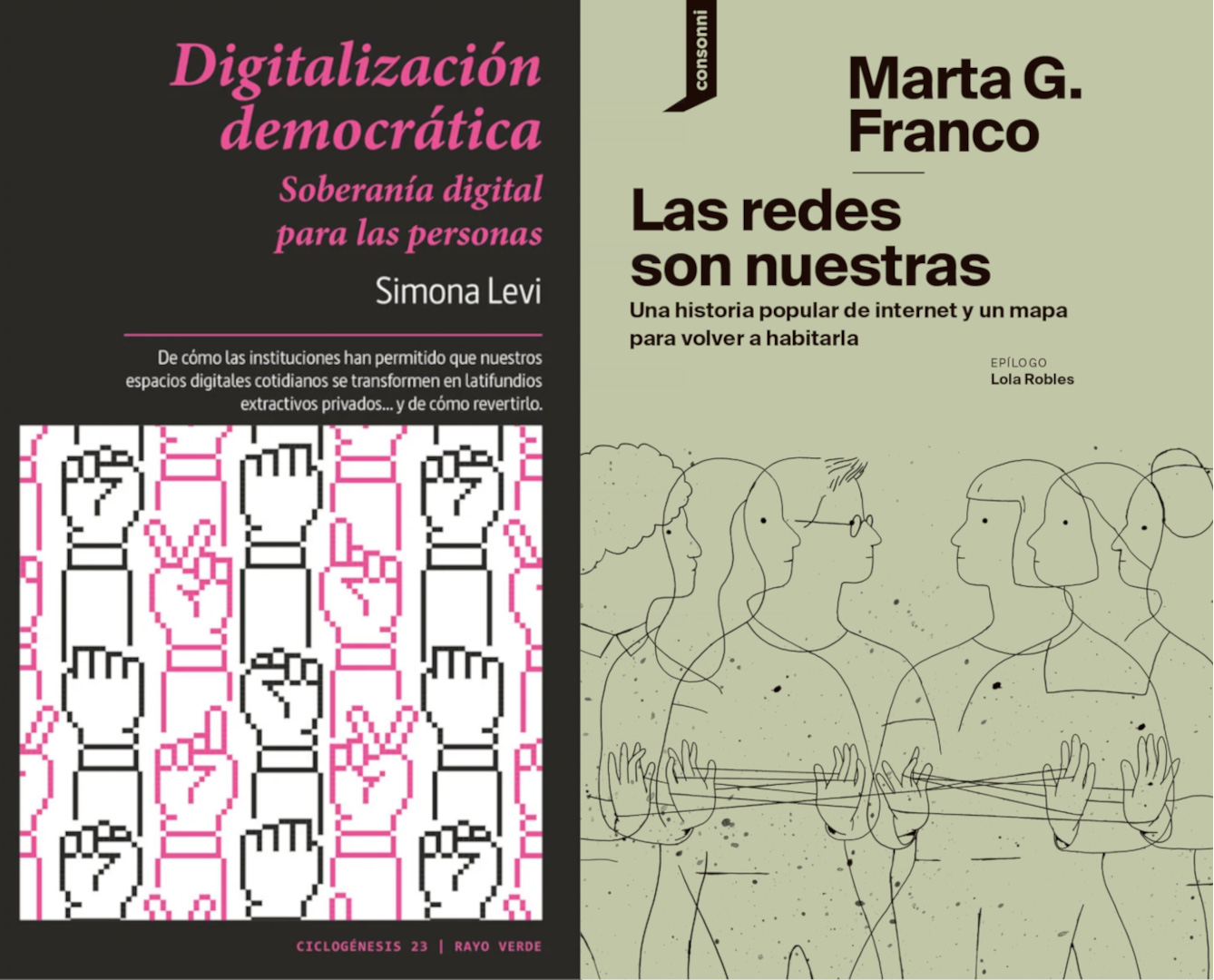

On November 15, we will celebrate in Errenteria-Orereta the three days organized by the different agents that make up Euskal Herria Digitala. This is a feminist digital self-defense workshop and a talk about democratic digitalisation.

The members of Movie Tech will offer the... [+]