The language of chickens in danger of extinction

- The Ongout language is about to die. No one knows when it's going to happen, but it's not going to take many years. Only seven people hold the language. They live in southern Ethiopia, in the Lower Omo Valley. His people are in a forest west of the Weyto River.

Ganame Wado is probably the youngest of those who speak the type of good. Looking at the wrinkles on his face, he would say he is fifty years old. You have to guess the age here for physical appearance, because in this tribe you don't follow the calendar and nobody knows the year you were born and, therefore, the age you have.

Wado remembers the language that everyone around him spoke when he was a child. “My parents, and their siblings, all spoke of well-being. Today, you ask kids something in this language and they don't know how to answer. Some may understand something, but not enough to answer.”

From the side, another man has taken the floor. “Language is difficult, and that’s why children have not learned. The Tsamay language is easier and they have grasped it.” This is Geda Kaula, another senior male. The language of the neighbors, Tsamay, has become the predominant language in the locality.

Basque Country of Africa

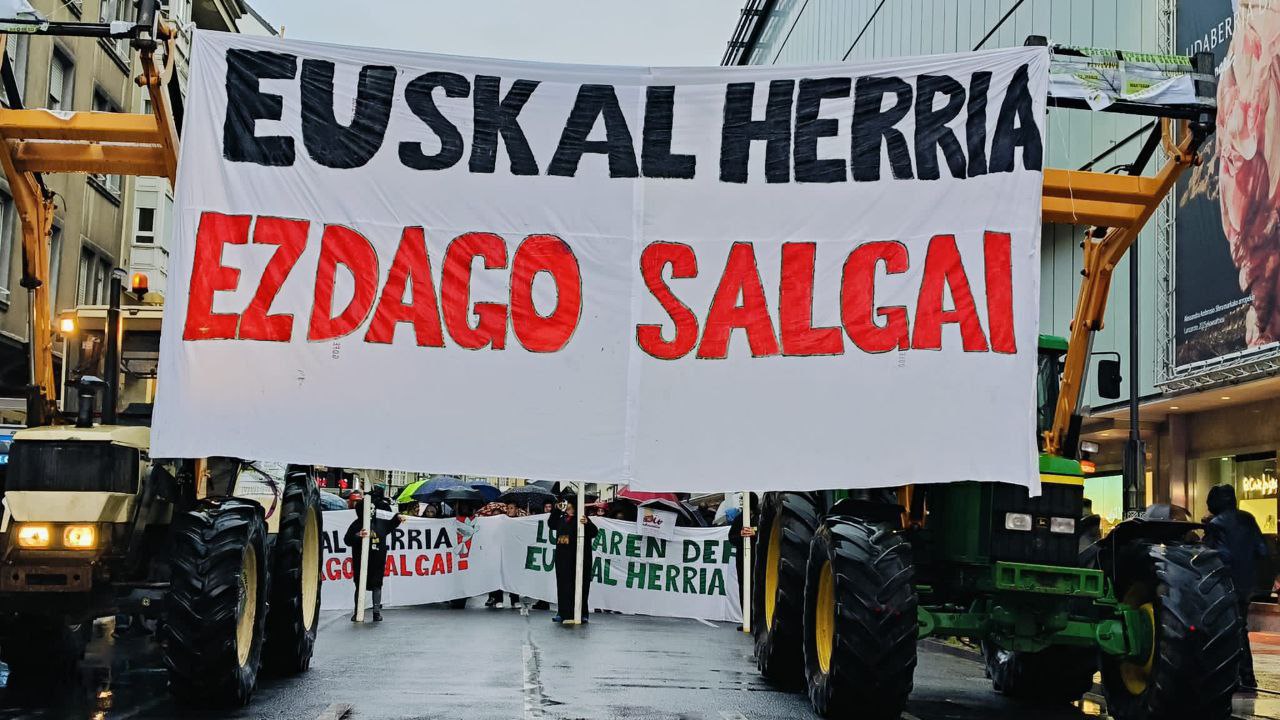

The type of language is an unclassified language. No one knows where it comes from, what other language can be attached to. That is why the Sicilian linguist Graziano Sava compares him with the Basque language. “When I proposed to my thesis director to study this language, I used this title: Ongout, African Basque. When he saw the title he immediately accepted the research issue.”

Some linguists say that the welcome is from the Nilo-Saharawi family. Others claim to be Afro-Asian. Aklilu Yilma, a linguist at the University of Addis Ababa, believes that it is a native language on the ground, gathering input from speakers from both sides. “The Ongots themselves say that at this point of the Weyto people were established from different places. They came from places like Maale, Banna and Borona. However, they could not understand each other and all created the common good.” Taking into account the names of place and clan, Yilma gives credibility to this theory, “because they use many names of those sites that cite them as their origins”.

Morphology is also a special language. According to Graziano Sava, “all the languages of the environment have a very rich morphology, with numerous suffixes to express genres, plurals and others. On the other hand, the type of good in that sense is very simple.”

The reason for the loss

Although the people of Ongot often wonder why they have stopped using their language, a strong answer cannot be found. Geda Kaula repeats what he said earlier: “Our language is very difficult, it’s hard to learn. Tsamay is an easier language.” However, there is no difficult language for the mother who receives herself from childhood.

The loss may have more to do with the socio-economic condition of the Ongout community. According to Aklilu Yilma, “it has been an undervalued community. They have no livestock, they are just farmers, and the one who has no livestock in southern Ethiopia is no one.”

In the village of Ongot, around the huts of bamboo wood and dried herbs, you see only a few chickens. “Those around them call them selflessly guarded with chickens,” says Yilma.

“We are peasants,” says Geda Saula. “We work corn and sorghum in the field. In the forest, we have bees from which we take honey. We've never had animals."

In the eyes of the new generations, the lives of the neighbours are better. They regard Tsamays as socially more advanced and, consequently, their language. According to Sava, “the young people say that the language of good is not useful, it is difficult and also archaic. Many times they deny that they are a type of good and say that they are a tsamay.”

The blessed come to the Weyto market on Saturdays. It's a dozen kilometers away from her village. They put their crops on sale and buy other products they need. They sit in the shade of a large tree and drink in the company of an alcoholic beverage of fermented corn, gola.

In the location of the fair, the social position of the people is evident. Most of the Ensanche is occupied by the Tsamais, and all good sits in a corner. They also relate to others, but they have their place to sit.

Maale Goda, a woman who, according to linguists, does pure and beautiful good, has confessed to us at the fair that she feels sorry for going to lose her language. “I wish children retained the language, but no one does it.”

Erre Sagane, an old lady sitting next to her, has been a little angry with the question. “What do we do? If no one continues to speak, it is not our fault.”

Graziano Sava has noticed that women have more developed awareness of loss. “Men are always easier to adapt to new social customs and, in this case, they have become easier to the way of life of the Tsamayas. However, women have fewer opportunities for and remain in social change. Now you see that yours is being lost, your language, your identity…”.

Is it possible to revitalize?

No special tests have so far been carried out for the maintenance of the language. The Administration, in its language registers, does not even recognise that it is a type of good. However, Aklilu Yilma does not blame governments. “When the language is going to be lost, when it is not used, who is to blame? The government? Linguists? No. The responsibility lies with the community that has ceased to use that language.”

What is clear is that the community is conditioned by the context and that the elements that guarantee the transmission of language, such as the educational system, are set by the administration.

In the village where the Ongots live there is a small school. The teacher teaches two hours a day to about twenty children. The Amharera and Tsamay languages are used.

According to Graziano Sava, the situation in Ethiopia is not the worst for minority languages. “There is no official language in Ethiopia. The administrative language is amaric, but all other languages are on the same level. The Government allocates money for textbooks in several languages, but it is not easy to use the available resources correctly. In the south of the country alone there are 44 ethnic groups that use so many other languages. In those languages that have never been written so far, preparing material and offering education is not easy.”

However, the few Ongout speakers hope that the language will be reanimated in their school. “Tsegaye is preparing the book, and once they do, we will again teach children good at school,” says Geda Kaula.

Tsegaye is Graziano Sava. Natives call it that. In addition to documenting endangered language, he is preparing the grammar book and the ong-tsamay-amharera dictionary. “It is more likely that it will now be inevitable to kill the language. But if you are really aware of what you have lost and want to teach future generations, have at least the material and the opportunity to start learning.”

When you lose any language, you lose a way of life and a way of describing the environment. The loss is irreplaceable. Sava believes, however, that when what is lost is an isolated language, the loss is greater. “The loss of languages such as Ongot or Euskera is more regrettable than the loss of any other language. Because they are the only ones, because there will be none like them.”

Ongota hizkuntza ez da, zoritxarrez, Etiopian galbidean dagoen bakarra. Ongotak bizi diren herrixkatik 40 bat kilometrora, arbore etniako gizon-emakumeak bizi dira. Ahuntz larruz egindako gonaz eta lepoko koloretsuz, dotore janzten dira. Komunitatea berez handia izan arren, soilik 4.000 dira arbore hizkuntza egunerokoan erabiltzen dutenak. Etiopia hegoaldean nagusi den oromo hizkuntzaren borana dialektoan mintzatzen dira gehienak.

Cabu hizkuntza ere arriskuan dago. Etiopia mendebaldeko eta ekialdeko bi barrutitan erabiltzen dute mila hiztun inguruk. Baso eta oihanetan bizi dira, oso oinarrizko nekazaritza eta abeltzaintza ogibide dituztela. Orain arte bizi izan diren eremuetan, ordea, kafe eta te soroak jartzen hasi dira hainbat korporazio handi. Kibebe Tsehay hizkuntzalari etiopiarra ari da hizkuntza hori ikertzen, eta berak dioenez, kafe produkzio honek kalte handia egin dio hizkuntzari: “Kafe eta te soro horiek jarri dituztelako, cabu komunitateko herri asko tokiz aldatu dituzte, eta beste hizkuntza batzuk nagusi diren herrietan sakabanatu. Hori kolpe gogorra izan da berez ahul zegoen hizkuntzarentzat”. Inguruko gobernuek ez omen dute inolako erreparo eta konturik izan bizileku aldaketa horiek egiterakoan. Arriskua handia den arren, Tsehayk ikusten du itxaropen izpi bat: “Oraindik badaude haurrak cabu hizkuntza lehen hizkuntza bezala jasotzen dutenak”.

Ezin dute gauza bera esan nayi komunitateko hiztunek. Haur bakar bat ere ez da hizkuntza ikasten ari. Komunitateko gizonek hartutako ezkontza joera berriak dira horren erantzule. Aklilu Yilmak azaldutakoaren arabera, “nayi gizonezkoak kafa etniako emakumeekin hasi dira ezkontzen. Ama arduratzen da beti umearen heziketaz eta amak kafa hitz egiten duenez haurrari ez zaio nayi hizkuntza iristen”. Oraindik 2.500 hiztun geratzen direla dio Yilmak, “baina gakoa umeek ikastea da. Hizkuntza umeengana ez bada iristen, jai dago”.

Kuwegu, argoba, anfilo… Hiztun oso gutxi dituzte hizkuntzok eta arriskuan dauden hizkuntzen zerrenda luzea da. Unescok iazko udazkenean argitaratutako hizkuntzen atlasaren arabera Etiopian erabiltzen diren 83 hizkuntzetatik 24 daude galtzeko arriskuan. Azken mende erdian hiru hizkuntza galdu dira Afrika ekialdeko herrialde honetan.

BRN + Neighborhood and Sain Mountain + Odei + Monsieur le crepe and Muxker

What: The harvest party.

When: May 2nd.

In which: In the Bilborock Room.

---------------------------------------------------------

The seeds sown need water, light and time to germinate. Nature has... [+]