Chronicle of the crisis

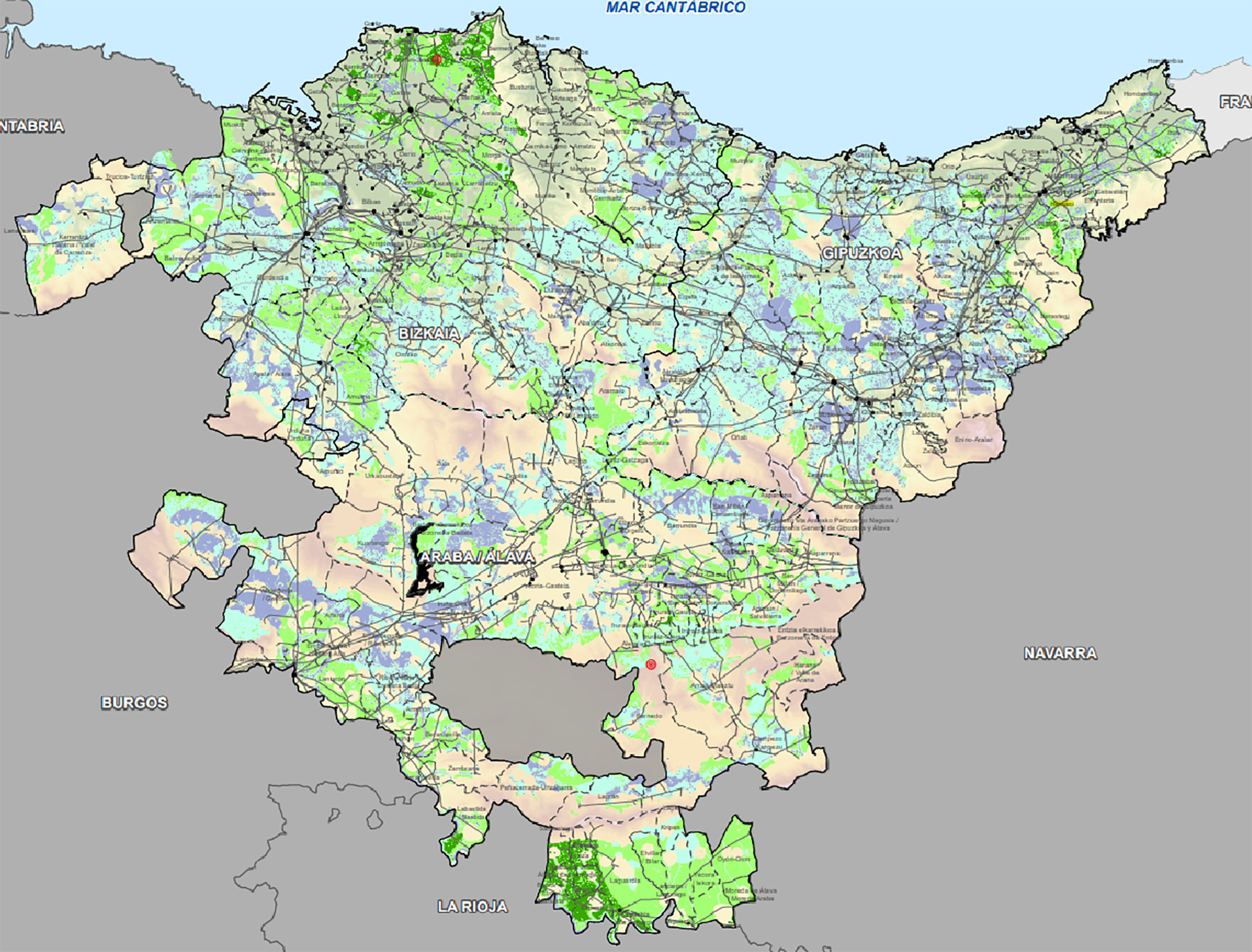

- The Left Bank of Ibaizabal (Bizkaia) is the birthplace of the Basque industrial revolution. It was here that, in the last quarter of the nineteenth century, shipyards and high ovens were created that employed thousands and thousands of people. With their support, the demographic and economic growth of the region seemed to be uninterrupted. A hundred years later, but in the 1980s, the remodeling promised by Europe abolished this state of well-being. In 1978, Sestao had a population of 42,905, today it has 29,500. Without overcoming the consequences of that nightmare, the crisis has once again punished: It is the municipality with the highest unemployment rate in the Basque Country.

Next to Ibaizabal, in the lower part of Sestao, which was once marshes in the 19th century, remembering the Altos Hornos de Vizcaya (AHV) factory that once employed 10,000 people, the María Ángeles high oven still stands. Nearby we have the compact steel mill after AHV, ArcelorMittal, and the shipyard La Naval, the last witnesses of Bizkaia in iron. Crossing the railway line, we have the neighborhood of Txabarri. Here is where the past and present of Sestao converge: We are confronted with the homes of workers who are demolished by the crisis of the 80s and, in order to bring the neighborhood to a good state, with public works in operation.

They have disappeared, but the old bars where the workers were fed and drunk. Since then, Sestao has lost around 15,000 inhabitants. The unemployment rate is 21.6%, the highest in the Basque Country. “Since the remodeling times, the Left has been the region with the highest unemployment rate in the Basque Country, where Sestao stands out. From then on, we can say that we have not raised our heads. The old numbers could have been portable, but the town has not recovered,” explains Maribel Vadillo of Cáritas.

New people to Cáritas

To the traditional marginalized who have always used the services of Cáritas, a new type of people has been added: “While we continue to work with gypsies, people with serious health problems and those who are trying to get some public support from the institutions, we have new groups today. What is striking is the massive appearance of very immigrants, who currently represent 70% of those who come here: Most of them are those who have worked in construction and/or hospitality in Spain for several years and now, due to the crisis, have become unemployed. The situation here is better than in Andalusia or the Canary Islands, and because there is more public support, immigrants have come here,” says Vadillo.

Another group consists of those who have had temporary contracts: “Some continue to receive unemployment benefits and/or additional aids. They move forward with the help of the family. They worked in La Naval or in construction, and although they have had temporary contracts, they have never been without work. They're people with jobs who can't find a job these days. Many of them have come here for the first time”, says Begoña, who works in the reception service of Cáritas. “They don’t want money, they want work. They're paying their mortgages and they can't keep their payments. In addition, even once they lose their home, they face debt, as the homes are valued at very high prices.” In fact, house foreclosures are becoming more common. Single-parent families – mainly women – and unemployed workers over 40 years of age are the most affected. Young people usually don’t have access to a home.

The Assembly of the Unemployed Is Back in Action

The Assembly of the Unemployed of Sestao was born twenty-30 years ago with remodeling. His partner, Txetxe García Montes, agrees with what Begoña said: “People have started coming back to rera, just like before. Although there are young people, we also have trained personnel of fifty-five years. They are based in La Naval, Babcock & Wilcox and ArcelorMittal. All of them are in bad shape, so they have lost their temporary contracts.”

As we have said before, unemployment has brought new housing problems to this area and has given Sestao a new appearance: “Some have lost their homes and others have had to leave. Although they have built new and officially protected houses, since most of the houses in Sestao are old and small,” says Maribel Vadillo, “In this way, young couples find it easier to find the type of housing they need in other municipalities and at the same price. The old houses are now inhabited by immigrants because they share them.” As a result of all this, the population of Sestao has become obsolete. The existing children belong to immigrants – the number of immigrants has increased by 40% in recent years.

2,755 are unemployed in Sestao. Of these, 1,441 are men and 1,331 are women. Half of them are young. 65% are not trained and their chances of entering the labour market are becoming increasingly scarce. Although it is not a good time for the industrial sector, it is where most Sestaos work. Services (1,649 unemployed) and construction (458) are the most penalized economic sectors.

The invisible crisis this time

Transporter Gustavo Izquierdo had to leave to work. Today, he lives in Agurain. Once upon a time he returns to the village to visit his family and friends: “The crisis has affected some specific sectors and they have had to give up several things. Everyone else – whether they have a job or are supported by their family – continues to do the same: they go out on the street, they go to bars... I see enough people when I come to Sestao.” Next to us is the bartender Juanma Blasco, who confirms Gustavo’s comments: “Despite the crisis, there’s another bar before, people want to forget the situation, which they can’t do when they’re at home. The same with the stores, although the consumption has decreased.”

There are simple shops in Sestao: traditional grocery stores, bazaars... “It is true that we do not have quality trade, there is a lack of shops to buy clothing stores and/or electronic household appliances. We have the usual, but without renovation,” says Begoña de Cáritas.

The situation doesn’t seem as catastrophic as it did in the 80’s: “The current structure is not 30 years ago. The impact of the crisis is now invisible. In today’s social system, even if it is outside the labor market, it is still possible to maintain consumption, even in Chinese stores,” explains sociologist Jakue Pascual. “Today’s society has eleven layers, it is not as homogeneous as the previous one. The tensions between the extremes are greater. That’s where we have those who depend on social services, those who have just become unemployed, those who manage to survive thanks to temporary contracts, the traditional workers – currently only a third of the working class –, the civil servants, the new middle class, etc. The new crisis, therefore, does not have the same reflection on the street as its predecessor.”

As usual, the promotion of public works has been the institutional response to the crisis and unemployment. We have the Ñ plan, the Bet for Sestao or Sestao Berri initiatives promoted by the Provincial Council of Bizkaia (PNV) and the City Council (PSE). The City Council has created 650 jobs through public works, but the works for the urbanization of the town are about to end. The hope lies in the optimistic forecasts of ArcelorMittal this year and in the new contracts acquired by La Naval through public capital. “All these things are just patching,” says Begoña. “Existing courses, for example, are of no use, do not serve to find work. They are looking at elections. It’s a very long list.”

Txetxe García Montes knows the subject well: “I have done all kinds of courses and although many of them can be useful for entering the labor market, they do not remain at all because they require us to have work experience.” The situation is worrying for the unemployed: there are few job opportunities and the weak economic fabric of Sestao is unable to create more jobs. “The situation has stimulated the work done in black. Employees have no rights. Many will never reach retirement, they are privatizing health and pensions,” says Begoña thoughtfully. For many, the worst is yet to come.

I don't want my daughter disguising herself as a Gypsy in the caldereros. I don’t want Gypsy children at my daughter’s school to dress up as Gypsies in caldereros. Because being a gypsy is not a disguise. Because being a gypsy is not a party that takes place once a year, with... [+]

Zerbait egin beharra izan liteke aurtengo Argia Sarietan garaikurra jaso berri dutenen oinarria. Zapalkuntzaren, bazterkeriaren, ahanzturaren aurrean antolatzearen erabakia hartu izana. Edo ilunetik argia ateratzea, zirrikituak bilatzea eta komunitateari eskaintzea. Balio... [+]