Political attacks on uncomfortable stories

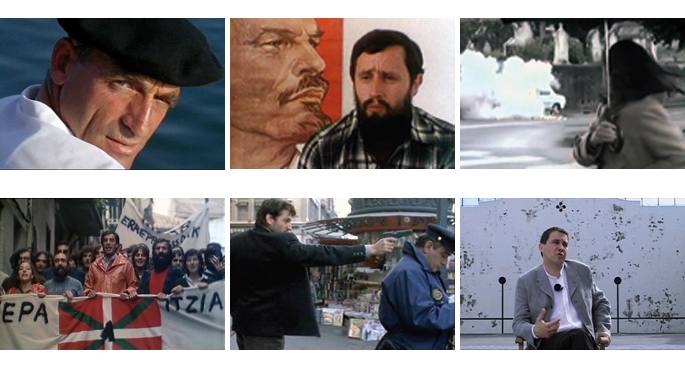

- Political issues are always close to controversy, even in the cinema. From Ama Lur to the Basque pelota, the films here that have spoken about the Basque Country and especially the Basque conflict have been accompanied by censorship, boycott, debate and turmoil.

“Cinema can say everything, it has the greatest artistic integrity and is the best form of communication. It catches you completely and disturbs your feelings. And that’s why it was so bad for the Francoists to have the film Mother Earth and not a book for example. After facing all the censorship, difficulties and obstacles, when we premiered the film in the Astoria cinema in San Sebastián and I saw that extraordinary response from the people, ‘Fernando, we have won’, I told him.” This is what Néstor Basterretxea, author of the film Ama Lur (1968) with Fernando Larrquert, says.Looks of celluloids. In the book Conversando con 13 directivos de la País Vasco (Together), several directors have talked about many topics related to cinema, but in their career we have noticed that a question is repeated: every time they have touched on politics in a film, controversy has arisen around them.

Ama Lur was the starting point for the modern film industry in the Basque Country, whose objective was to turn it into a cry against the Spanish dictatorship. Of course, during the dictatorship, it was not easy. As they rode, they had to say that they were working for the NO-DO once or twice when some authority approached. Every time they made a reel (about 12 minutes) they were forced to call it censorship and they made the appointment in a small movie theater. This is explained in the book The Bastions: “We went into the room and put it on the front. Then they would turn off the lights and go in, three or four, in the dark. We watched the tape, heard some gossip, came out of the room and turned on the lights. We didn’t see their faces, but a week later I had to go to the Department of Information and Tourism of Spain, and the brother-in-law of Fraga Iribarne, Carlos Robles Piquer, rebuked me immensely to remove this and put it on.”

Censorship consumed, for example, the snowy tree of Guernica, which had to be replaced with the same tree extracted in the spring, “to show the appearance of a happy country within Spain and not of a dying people”, or the Guernica painting by Picasso. They had to include the word “Spain” in several passages of the voice off; and they were ordered to put in, among other things, the renewal of the “Spanish novel” by Pio Baroja. They also feared that the work would be kidnapped, but in the end it did not happen and they were able to premiere it successfully in San Sebastian. Moreover, it is said that Fraga himself was frustrated by the good reception that Mother Earth had.

Years later, the documentary series Ikuska, directed by the San Sebastián filmmaker Antxon Ezeiza in the early 1980s, which addressed the social realities of the Basque Country, had problems. The first documentary was called Referendum (1979) and was not accepted by the financiers because it dealt with politics. “That’s where the politicians went with the stopwatch, from one side to the other, to measure exactly which of them took the most seconds. It was not included in the project, but we were told that we could give it in cinemas, but if we put it in front of us ‘watch out, it has political content’. How can it not be, with the title of Referendum? !”, says Ezeiza. The work Days Between Smoke (1989) by the San Sebastián was also the target of the Spanish media, which accused him of an extreme patriotic attitude, although the director often reiterated that the film does not have a specific ideology and wants to reflect the suffering caused by the Basque conflict.

Not the Spaniards, some left-wing nationalists criticized the love of Koldo Izagirre in Off (1992). The film focuses on the love story between three people, as the girlfriend of the prisoner begins a new relationship with a third friend. The prisoner's friends will not tolerate this relationship, and several accused the passer-by of depicting his friends as intolerant.

General Del Bosch did not want a film of the Burgos process

Director Imanol Uribe has addressed the Basque conflict on the big screen several times. He found the greatest number of obstacles with the documentary The Burgos Process (1979). It was to be premiered at the San Sebastian Film Festival, but it was revealed in the media that they would not allow it to be screened, and the copy of the film had to be hidden. Uribe explains in his book that General Milans del Bosch had heard about the work a few days before, and all the alarms were raised. “Nobody saw it, nobody knew what it had or who I was... and they were afraid of how the film had dealt with the subject.” Bosch immediately called the Spanish Foreign Minister, Marcelino Mayor Oreja, and his nephew, Jaime Mayor Oreja. The latter asked the director to meet individually on the eve of the performance. “It was a four-minute conversation. He asked me: “How much would it cost to get the film out?” And I answered: ‘That is outrageous. It would be the first time in the history of cinema that a director withdraws his film from a festival. Kidnap him or do what you have to do, but the jury has selected the film and I will not take it away.’ And that’s where it all ended.” The high voltage pass was the first performance of the Burgos process, full of police, but nothing happened.

With the film The Escape of Segovia (1981), about the 40 members of ETA who managed to escape from the Segovia prison in 1976, Uribe was accused of spreading the message in favor of leaving arms. “It was only criticized by miles; at that time there were discrepancies between miles and poly-miles.” With the successful death of Michael (1984), he played a role in representing on his lists members of the Patriotic Left who do not want a homosexual. For the people, “I belonged to the Union with the Burgos process, to the Basque Left with the escape from Segovia, and to the PSOE with the death of Mikel. I didn’t belong anywhere, I didn’t work anywhere.” Although

he neglected political issues for a while, in 1994 Uribe addressed the love story between ETA and a prostitute in Días contados (1994). He won the Golden Shell at the San Sebastian Film Festival, but in connection with the film, the director has another memory nailed to him. In 1996, the film was broadcast on television the day after the assassination of the politician Fernando Múgica by ETA. “In the newspaper El País, Vicente Verdú almost accused me of shooting myself. When you deal with these kinds of issues, given the reality, it’s complex, they can happen to you...”

Boycott of Professed Members to ‘Yoyes’

Helena Taberna chose the bad and controversial event of ETA’s career for her first feature film Yoyes (2000): Life and death of María Dolores González Katarain ‘Yoyes’, the first female leader of the armed group. “Because people didn’t know me and it was a complex issue, I made assumptions everywhere. Some actors did not want to participate, not even several technicians... Since I had the idea, it took five or six years to execute the project because a lot of producers did not accept the project. And they also put obstacles in my way, telling the producer ‘be careful where you go, you’ll see...’ and such things, on the part of different creators, on the part of the members, that’s more sad; you know everything over time...” Once the film was presented, it received two main criticisms: Because of the image of the PSOE party, the Spanish Ministry of the Interior and its connection with the LAG, and from a sector of the Patriotic Left, who did not agree on how the film reflects the behavior of ETA with Yoyes. The fact that ETA’s ceasefire ended just then did not help the film at all in offering it to its distributors.

Finally, as a sign that the censorship and boycott of political power has survived for years, the Basque ball of Julio Medem has been celebrated. Leather against stone (2003) Dusts proudly proudly proudly proclaimed by the documentary. “For the members of the association of victims of terrorism AVT I have fallen short because I have not been able to criminalize nationalism in my film with the same violence that they criminalize, and I have not made it clear that the worst political evil of Spain (after ETA) is the PNV (...) Someone close (someone who loves them and is willing to listen to them) should tell the members of the AVT, one by one and in the ear, that being a victim of ETA does not give them any political or ideological reason, or the right to insult, as they think,” This is an excerpt from the letter that the San Sebastián director sent to El Mundo in response to the violent persecution that the film received from the Spanish right-wing. When he was selected for the Zabaltegi section at the San Sebastian Film Festival, María San Gil, then PP spokeswoman for San Sebastian, and Pilar del Castillo, then Spain’s popular Minister of Culture, asked to be removed from the festival. He was also selected for the Spanish Goya Awards and Medem has confessed to having spent the worst day. “I don’t think I’ll ever have a day like this again, or deserve it. A lot of people who protested against me didn't even see the movie. The journalists asked: “Did you see it?”, “No, of course. How are we going to see that?” Against the Basque Ball, against the bullet... I can understand that I don’t like the film, that I don’t like the fact that the widow of a dead man in the attack and the wife of a prisoner go out together... But to tell you from there that I was working with my film to encourage someone to shoot... It’s so stupid! It was like living in the Franco era again.”

Helena Taberna says it clearly in the book: from the moment the film has a historical-political context, those on one side and those on the other will see the opposite. Being liked by everyone is not easy or reliable.

The above passage is from the book Celluloid Looks. On the blog, I have received several other passages from the book in the post Few and Misrepresented Women in the Cinema.

Itoiz, udako sesioak filma estreinatu dute zinema aretoetan. Juan Carlos Perez taldekidearen hitz eta doinuak biltzen ditu Larraitz Zuazo, Zuri Goikoetxea eta Ainhoa Andrakaren filmak. Haiekin mintzatu gara Metropoli Foralean.