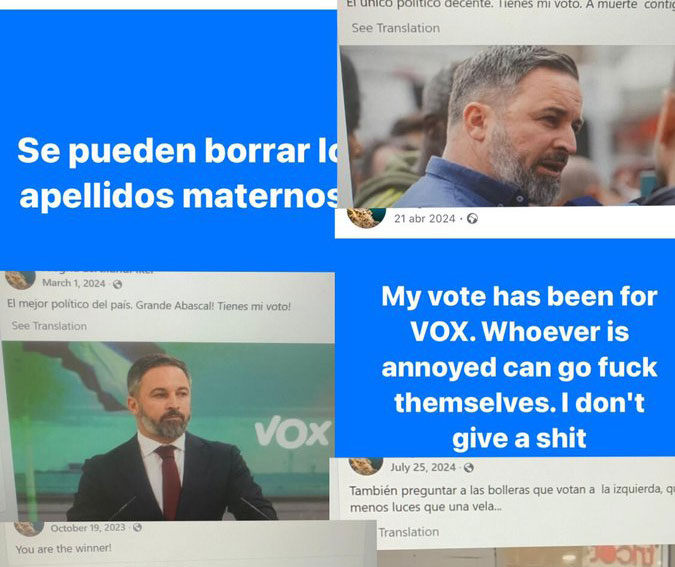

"The Arab world has been waiting for this for a long time"

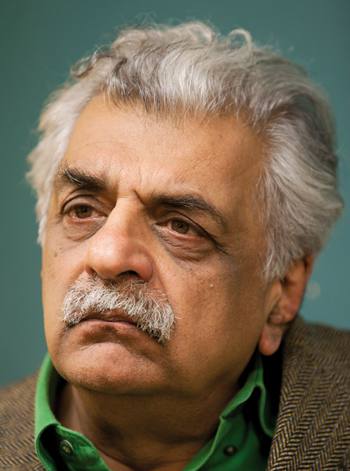

- The day Tariq Ali came to Pamplona, the Arab countries are in a red rebellion. In Tunisia and Egypt, governments have fallen; Libya has not yet become the first news item in the news, but the atmosphere is hot. We spoke with Ali before the conference organized by Zabaldi at the Golem cinema in Pamplona, in the bookstore La Hormiga Atómica.

Do the events of the last weeks in Egypt put us at the beginning of a new era?

I would not necessarily make such a statement, but it marks a turning point in the Middle East for the first time since the late 1960s and early 1970s. The 1967 defeat of Syria and Egypt against Israel – with the help of the West – broke the bone behind Arab nationalism. It was also designed to do so. The Egyptians have been plunged into this period of defeat ever since. It is interesting to contrast this: After the 1967 defeat, the leader of the people, Gamal Abdel Nasser, resigned saying, “I accept responsibility for the defeat, I will no longer be your president.” Millions of people took to the streets saying “don’t go!”; “It’s bad enough that you’ve lost, we can’t risk losing you too.” So they dragged him back to command. Years later, when his heart was broken, he had no money in his bank account; he received only his salary. The contrast with Hosni Mubarak cannot be greater: millions of people asking you to leave because you refuse to leave office.

It’s a big turning point and it will take time. I would say that the next decade will be decisive to see how the Arab world will look, but in any case, these uprisings have changed many things: perceptions, the level of political consciousness... and that is very important. In addition, the West was told: “You have supported these dictators. We are the ones fighting for freedom.”

That’s as far as the Arab countries are concerned, but U.S. foreign policy will also have to change its discourse, right? Thanks to these massive civil movements, any initiative that could have been presented as a “war on terror” has been completely dismantled...

It never made sense, even the name was foolish: “The war on terror”... This only served to scare people, the real war was made to establish U.S. domination on a global scale. They used terrorist attacks against the United States to shape the world according to their interests and that was what they said to each other, initially in secret, then in public. That's why they occupied Iraq, that's why they occupied Afghanistan... they thought they could control the Arab world, but the uprisings in Tunisia and Egypt have shown that Arab countries are not so easy to control.

From this point of view, the United States is working out of time trying to create a regime in Egypt that is, of course, more democratic, but that works with them. They will fight very hard to prevent their hegemony in this region from being broken. So, although moderately, I’m optimistic; I’m very happy with the uprising that has happened, but the issue doesn’t end there. The conflict will continue on multiple levels. They are basically saying that the transitional government, that is, the Egyptian army, should say what the future will be like, while the mass movement wants a new, completely new constitution that incorporates social rights. It will be a struggle and the big question is: if it becomes necessary for the mass movement to go out again, will people go out or not? I think so, but I'll have to see.

You have often criticized the mainstream media. Much has been said about the importance of the Internet and social networks in the Egyptian movement, but has anything really changed?

I don’t think so, I think it’s an exaggeration of the importance that has been given to this issue. It’s something that the West emphasizes to feel good: “Look, they’re using things we invented.” But, you know what? There were revolutions even before the telephone was invented; and when the telephone was invented, it made things easier because it allowed people to call from one city to another, “We’ve done this in our city, what are you doing?”... But before that, messengers were sent or telegrams; before that, it worked word-of-mouth; people use the tools they have at their disposal. If they are better instruments, more efficient, perfect! But tools work in situations where people have reasons to use them.

Maybe the impact of Al Jazeera was different?

Al Jazeera has been important because it is the only television in the Arab world that people believe in. They don’t believe what their country’s TVs are saying, so when Al Jazeera started telling what was going on in Tunisia, all of Egypt was watching. In that sense, it was incredibly useful. I have many friends from Egypt and they looked at the Tunisians as if they were the most vulnerable people among the Arab countries. “Can they do it? So did we,” they said, and now people are saying, “Did the Egyptians do it? We can do it too.” Al Jazeera has contributed a lot to this, that is why the signal was cut in Egypt, that is why the chief correspondent of the country was banned and arrested. But it was too late.

So the simple fact of saying the truth is still, in your opinion, a tool for revolution.

Oh, yeah, yeah. Providing truthful images to people is very important. Just look at the footage you were receiving on CNN World in the early days of the conflict, or what the BBC was offering, which was even worse: They were interviewing people from the West or at least Arabs promoted by the West; and on the contrary, very few people were involved in the conflict. This began to change when it became clear that Mubarak would not last. But Al Jazeera didn’t do that; he continuously filmed mass mobilizations, talked to X, Y, Z, got people’s views and that was important.

That’s why the West is shaking Al Jazeera: TV bombed its offices in Afghanistan and killed Baghdad’s chief correspondent when he was reporting on the war in Iraq, even though Al Jazeera told the United States “please don’t bombard us by mistake, here are our offices.” They pointed it and set it on fire and killed the journalist. Very rarely are they found as Al Jazeera or Telesur of South America, they report completely from a different angle.

And what happens to us here, then? That is to say: we have independent media at our disposal on the Internet, no problem to know what is happening, but until the situation strikes us directly there is no movement...

The TV images are very useful, but in a vacuum they can do nothing. Conditions are needed, then images like those of Al Jazeera become useful. You know, the Arab world had been waiting to do this for several years, people were angry, they were fed up. There is another problem in Europe, if you compare it to the Arab world. If you have several political parties in Europe and these are the ones that channel different experiences; in the Arab world the parties were illegally present and this has made the mass movement extremely rich because a single party has not been able to confiscate its intentions. Here you have the right, you have the PSOE, you have the new social democracy...

In the midst of the French movement against pension reform, for example, socialist politicians were asked: “If you get the power, will you reverse this restriction?” They said no, more or less clearly: “Yes, we will do something, but we will have to see...”; no, that is, they would do nothing; and the mass movement did not say fits. So until there is a complete rupture with the parties that collaborate with this degenerate form of capitalism, I don’t see how it can advance in Europe.

There is no hope in Europe.

It seems not at the moment. But you never know, don’t think that because nothing happens now, nothing will happen in four years. Something can be triggered, people are angry in Europe, but also without help. That’s how the Arabs have felt for 25 years and finally the anger explodes. Political consciousness is never linear, it goes up and down and one day it touches the sky: then there are uprisings and revolutions.

To continue with the world of information, what is your opinion about Wikileaks?

With Wikileaks you have to understand: That when the West is waging wars with little acceptance, occupying countries, killing people... there will always be someone inside the establishment who finds it abominable, willing to make leaks. The Pentagon papers were leaked during the Vietnam War; the documents that Wikileaks has now published have come into their possession by U.S. soldiers in Iraq. The bravery of these soldiers is admirable, because they know that if they are caught they will go to jail and yet they have done it. That's a great inspiration.

This time they have contacted people who are dealing with new technologies, hackers. This has allowed them to put all this information on computers and it has become impossible to hide it. At the time of the Pentagon papers, for example, there were no computers and a lot of papers had to be photocopied and distributed to two or three people! [laughs]. Now it's up to everyone, you can go and read...

Yeah, but they're using the big media to spread the message:The New York Times, The Guardian, El País...

I think it's a good thing, it's a positive development. We have seen the Spanish Foreign Minister say to the Americans “please don’t be angry with us because we have left Iraq, we will do more in Afghanistan”. It shows how these people talk to each other, who dominates, who is the weak side.

You have often stressed the importance of history in understanding conflicts. Is the lack of history education the most important factor in understanding how we are manipulated?

It is one of the factors, not the only one. The emerging world of neoliberal capitalism is designed to institutionalize political apathy if you look closely: culture, politics, economy... In the economy, until the crisis arrives, even after that, we have been told: “take the money, spend it, buy it, buy it, buy it”. Consumerism, such values, individualism: “You can do everything yourself, don’t worry.” And it never works that way, but people have been stuck in that dynamic until the 2008 crisis comes. People are starting to think again. For example, during the recent student occupations in Britain, I went to talk to some of them and the questions they asked me were as follows: “How was it in 1968?”, “What were your demands?”; and I explained the similarities and differences to them. Therefore, when people start to move, the need for history immediately arises, that is why the authorities, with full intention at times and involuntarily at others, have turned history into a discipline of very little acceptance. In addition, it is shown in modules to contain the population so that you do not place the entire photo in its context.

Several people have told me on this trip that the memory of the Spanish Civil War in the younger generations is very weak. What happened, why, how the war was fought, how it was won, how to lose... People have no idea. And I think the Civil War is very important to understand the reality of Spain today, but people don’t want to talk about it.

Not even the years of transition...

Not even about that: how the US organized the transition with the Spanish ruling classes through the collaborationist political parties. Because, the United States was very nervous that if they did not organize the transition in which Franco would participate, there would be events like those in Portugal. In Portugal the dictatorship did not organize the transition at all; and there were revolts in the army and waves of people overthrew the government. They wanted to avoid this in Spain and organized the transition from above, not from below, as in Portugal. This, in my opinion, left Spanish politics in a terrible mess. Franco’s state structures were not really touched: judges, officials, military, police... Nothing happened, it was just a follow-up. There were changes in Portugal.

In the book Empire and Resistance, you encourage the citizens of the United States to organize themselves against the imperialist practices of their country. Is the organized internal movement the most effective way to fight the Empire?

I think it is very important because the U.S. empire, for me, is economically weak and militarily very strong; it is even militarily overdetermined. Therefore, it can continue with this type of actions to solve its economic weakness. You take one country, no one opposes you, no other state in the world is ready to face you: The European Union is a joke, a mere appendage of the United States; China has no foreign policy, its presence abroad is very weak; Russia remains in its sphere of influence; there is no national opposition, except what has emerged recently in South America, you know, Chavez, Morales... But not on a global scale. Therefore, the empire cannot be brought down by war, as has happened in the past with other empires. It may weaken, with the revolts that arise in the countries it occupies, but ultimately, I think, something should come within the United States. Maybe I'm wrong, but I think so.

However, you have also criticized movements such as the Black Panthers or Weatherman of the 1960s, which believed that they could defeat the state simply by using violence...

The Black Panthers was a little different because it really showed their community that they had the right to self-defense in the face of all kinds of daily violence; and the state became so distressed that it ended up destroying the Black Panthers in an evil and brutal way. Weatherman was a student organization. They thought that the explosion of U.S. army facilities was the only way they could help the Vietnamese people. They attacked military property and facilities, not people, but the strategy was wrong. We had a great mass movement in the United States against the war and Weatherman, or at least the people associated with them, separated that movement.

In the same book mentioned above, you pointed out that the empire prefers the balkanization of nation-states, because in this way it can control them more easily. In your interview today [February 16] in Nuevo, you said that you prefer not to separate the Basque Country and the Catalan Countries from Spain. Can you explain that point of view more, please?

It is related to what you mentioned first. The time we live in is not the same as the 20th century. Since there were other social and political alternatives on a global scale in the last century – before China became a capitalist and before the collapse of the Soviet Union – even though these systems were weak, there was an obstacle to capitalism. Now we live in a world that is totally capitalist and if one country wants to divide itself from another that exists, but the social and economic system will remain exactly the same, then where is the difference?

I asked the Kurds who had supported the war in Iraq: “Will you be happy to be the protectorate of the United States and Israel in Iraq?” “We prefer that to be part of Iraq,” they replied. This is insane! For what reason? If you want to use that space to do something different, and the state stops you, then the alternative is completely different. In the 1970s I was editor of left-wing newspapers and we were very, very supportive of the struggle of the Basques; and I am still in favour at the political level, because repression is unacceptable. The behavior that the Spanish State and the European legal institutions are having is unacceptable, but I am not convinced that the division will bring anything positive, because the Catalan countries or the Basque Country will be basically the same. And you will see how an embryo that already exists, the oligarchy or the local elite, will behave in the same way and remain in the European Union. One of the problems we have today is the European Union: it is not democratic, it is a union made by bankers, it is corrupt, it does not offer hope to the people... Why be a part of it? But if social alternatives are built together with the new states, the issue is very different.

Isn't it connected in any way? Slavoj Zizek was here last year and said he would start to believe in the European Union when small nations like the Basque Country got directly involved. It proposed the regeneration of the European Union through small nations.

I don't agree with Zizek: He was in favour of the division of Yugoslavia; I know this part of the world well and I can say that the division was a disaster, a total disaster. In Slovenia, in Croatia, in Serbia, there are totally corrupt elites, no matter how corrupt they are, they are only making money: politics, money and gangsterism. There are three fingers: the politicians – centre-right, centre-left, it doesn’t matter – the control that money has over them, and the gangs that buy all the parties and have mafia-style businesses. There is a strong tendency for this in Europe and it is very important in the Balkans. The former Croatian Prime Minister is now in prison and... this is not the trend we want to see multiplied. In the old days, when we wanted countries to be independent, they were always socialist republics and we thought that this was how we could start, that is, we could create a federation with socialist countries that would cooperate. This seems like a utopia now; I’m still in favor of it but I think it’s very far away. Therefore, the demand for independence under current global conditions does not seem realistic to me.

Is socialism the alternative?

I think so: socialism and radical democracy. Radical participation at multiple levels, from local to national; and trying to recruit citizens there is very important. If not, what choice do we have? We have banker-controlled politicians, bankers controlled by politicians, it’s a symbiosis that is completely contrary to people’s interests.

But there is a certain fear of using the word...

They are afraid to talk about capitalism. People should worry about that, they're losing their jobs everywhere. You find a lot of people in Eastern Europe saying, “things were better before: we had work, cheap houses, cheap electricity...”. Citizens are losing the social rights they earned and here too, as states privatize everything.

You’ve written your last book about Obama and say, among other things, that he has formed a conservative administration.

Well, the European elites are also conservative and those Europeans who saw the leader who would lead them to the promised land in Obama must feel very stupid right now, because all they see is the continuation of the previous one. So when you see Zapatero in Spain trying to imitate Obama, or Veltron in Italy, both saying “we are like Obama”... Well, yes, you are like Obama, but don’t be too proud of that. For example, the majority of European citizens are against being in Afghanistan, as well as in Spain, Germany and Great Britain. The politicians ignore them. And the only reason these European countries are in Afghanistan is because the United States wants it, there is no other option. In addition, Obama’s policies in Afghanistan and Pakistan are worse than Bush’s: he has killed more people in Pakistan for himself. And even within the U.S., he's a Wall Street guy, so what's the difference? The color of the skin. But that's not enough.

Tariq Ali 1943an jaio zen Lahoren –gaur egun Pakistan, artean Britainia Handiaren menpeko India–. Gaztetan Erresuma Batura jo zuen, Oxfordeko Unibertsitatean ikastera eta geroztik hainbat borrokatan parte hartu du. Vietnamgo gerraren aurkako mugimenduan zaildu zen eta ezaguna da afera horretaz Henry Kissingerrekin izan zuen eztabaida. Munduari ezkerretik begiratzen dio, publikatu dituen liburuei erreparatzea besterik ez dago. Azkenekoan (Obama sindromea, 2010) AEBetako presidente berriaren politikak gupidarik gabe aztertzen ditu.

Erotzekoa behar du izan egiazki. Hiri batera iristen zara eta ezin konta ahala jendek hitz egin nahi du zurekin, horietatik ez gutxi, kazetariak. Bihar-etzi euren agerkariak suzko lili bihurtu nahi dituzte, gasolina eman behar diezu, debalde. Arratsalde osoa pasa du elkarrizketak eskaintzen, nekatuta dago, baina arrangurarik ez azkenekoa iritsi denean. Gero, bukatzean, hitzaldia eman behar duen aretora autoz joan nahi ote duen galdetu diote. Ezetz, nahiago duela oinez. Horri esker hiriaren historiaz zerbait ikasteko parada izango du. Golemeko txalo zaparradarekin amaituko da Tariq Aliren Iruñeko egun finlandiarra. Egun finlandiar luze-luzea.

Vagina Shadow(iko)

Group: The Mud Flowers.

The actors: Araitz Katarain, Janire Arrizabalaga and Izaro Bilbao.

Directed by: by Iraitz Lizarraga.

When: February 2nd.

In which: In the Usurbil Fire Room.