Society

Environment

Politics

Economy

Culture

Basque language

Feminism

Education

International

Opinion

friday 07 february 2025

Automatically translated from Basque, translation may contain errors. More information here.

The point is

Antton Olariaga

One day, a well-known comic book artist went to a Catalan school and showed his students the original that he was going to publish shortly after; among them was a young cartoonist who, while hand-in-hand with the work, suddenly secretly drew a tiny dot on one of the last few lines of the last page. With his secret and his curiosity, the boy had since often gone to the kiosk, and at some point the comic was released, and that’s his point, that’s his first publication! The boy bought all the specimens, just in case the point was in them all, and encouraged the starting point to draw after he was there. Although I do not remember the name of the now famous cartoonist, I remember the anecdote well, and I will use a license similar to the one he used to model and bring to us the story of Quim Monzó in the Great Long Ago (86 counts):

“And behold, at a reddish dawn, the hominid went to the entrance of the cave, and rose up on the two legs of the rear. His eyes turned downward, he saw the earth farther than usual, and this unusual verticality caused him such a sweet fainting. Glaring, he saw frightened flocks of animals in the glacier’s environment, and the inexorable sun was reflected in his eyes. He then felt such an impulse of happiness as when he was passionately embraced by some other member of the group he used to feel. And that hominid, having just discovered those two hands and ten fingers that had been feet, gladly and cheerfully drew the walls of the cave, and having hunted a beast, after his heart had eaten with bloodshed, he danced and cracked his hands, and at the head of all he drew musical notes to a skeleton like a tube.

And look where, in the blue sunset, the hominid made the discovery of the sky. Accustomed to using his eyes like the earth, he was fascinated by the unfinished dome of the sky, or he was already shining under Venus. With pain in his neck, he lowered his gaze back to the ground and noticed that his mouth was filling with voices: ‘Ah, oh, my child’; and soon: ‘U, lu, lug’; at one point, however, those like chili became more or less vocalized words: ‘Earth,’ and pointed his index finger at the bottom of his feet. His finger stepped forward, he threw ‘urg, gur, water’ looking at a stream; and ‘no, you, bone’ came out looking at the bones of the shattered beast; and he said ‘ur, zug, wood’ as he glanced at the trunk of a tree; and ‘el, ur, snow’ sprang up as the first flakes began to fade; and at the end he raised his head again, saying ‘urg, urt, urt, water’. Then a firm smile came out, and he put his hand into the water, and taking a bone, he struck the trunk of the tree, ttakun-ttakun-ttakun, and drowned all these new words in the mouth of a piece of snow. Like in the morning with verticality, he now felt halous, fascinated by those words that sounded. ‘Urg, geur, eus’ continued as the snow in his mouth melted, and more calmly, jostarliness: ‘eurk, water, errik’; and, cheerfully and cheerfully, ‘eus kal he rri a’, cut to perfection, and that irresponsible, pitiless hominid did not even notice the calapite or confusion he had just created.” Of course, in Monzó’s original

story, Països Catalans appears, but as I said, let me change the ending, because in this instant, it is up to us to give our history, instead of the little points of the symbols of surprise and question so far, instead of the points of interruption, a different point and a continuum that will not be the end at all, which perhaps will also encourage us in the new year.

“And behold, at a reddish dawn, the hominid went to the entrance of the cave, and rose up on the two legs of the rear. His eyes turned downward, he saw the earth farther than usual, and this unusual verticality caused him such a sweet fainting. Glaring, he saw frightened flocks of animals in the glacier’s environment, and the inexorable sun was reflected in his eyes. He then felt such an impulse of happiness as when he was passionately embraced by some other member of the group he used to feel. And that hominid, having just discovered those two hands and ten fingers that had been feet, gladly and cheerfully drew the walls of the cave, and having hunted a beast, after his heart had eaten with bloodshed, he danced and cracked his hands, and at the head of all he drew musical notes to a skeleton like a tube.

And look where, in the blue sunset, the hominid made the discovery of the sky. Accustomed to using his eyes like the earth, he was fascinated by the unfinished dome of the sky, or he was already shining under Venus. With pain in his neck, he lowered his gaze back to the ground and noticed that his mouth was filling with voices: ‘Ah, oh, my child’; and soon: ‘U, lu, lug’; at one point, however, those like chili became more or less vocalized words: ‘Earth,’ and pointed his index finger at the bottom of his feet. His finger stepped forward, he threw ‘urg, gur, water’ looking at a stream; and ‘no, you, bone’ came out looking at the bones of the shattered beast; and he said ‘ur, zug, wood’ as he glanced at the trunk of a tree; and ‘el, ur, snow’ sprang up as the first flakes began to fade; and at the end he raised his head again, saying ‘urg, urt, urt, water’. Then a firm smile came out, and he put his hand into the water, and taking a bone, he struck the trunk of the tree, ttakun-ttakun-ttakun, and drowned all these new words in the mouth of a piece of snow. Like in the morning with verticality, he now felt halous, fascinated by those words that sounded. ‘Urg, geur, eus’ continued as the snow in his mouth melted, and more calmly, jostarliness: ‘eurk, water, errik’; and, cheerfully and cheerfully, ‘eus kal he rri a’, cut to perfection, and that irresponsible, pitiless hominid did not even notice the calapite or confusion he had just created.” Of course, in Monzó’s original

story, Països Catalans appears, but as I said, let me change the ending, because in this instant, it is up to us to give our history, instead of the little points of the symbols of surprise and question so far, instead of the points of interruption, a different point and a continuum that will not be the end at all, which perhaps will also encourage us in the new year.

Most read

Using Matomo

#1

#2

Xabier Letona Biteri

#3

Estefanía Quílez

#4

Tere Maldonado

Newest

2025-02-07

Xabier Letona Biteri

A. A. A.

That Aznar helped Aitor Esteban?

Aitor Esteban will be the next president of the EBB of the EAJ and the EAJ will thus sell that, with the renewed leadership, the new leadership is ready to continue the process of renewal of the party.

2025-02-07

Onintza Irureta Azkune

Aggression against the linguistic requirements of the local police in Donostia, Astigarraga and Usurbil

The City Council of Donostia-San Sebastián appealed in September 2024 because in January of the same year the judges annulled the B2 language requirement of both municipal police officers. The Supreme Court of the Basque Country will not even refer the appeal to the court... [+]

2025-02-07

Xabier Letona Biteri

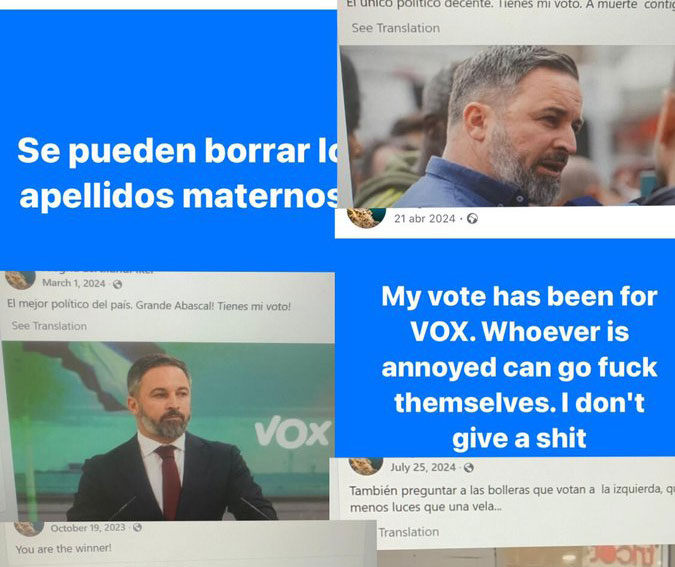

Ikama denounces the professor of the Alava Campus of the UPV/EHU who disseminates "fascist messages"

Ikama, a professor at the Faculty of Pharmacy of the University of the Basque Country (UPV/EHU) in Vitoria-Gasteiz, has denounced the dissemination of “fascist messages” on social networks. Last September, the UPV expelled a professor from the Leioa Campus for his messages on... [+]

2025-02-07

Gorka Peñagarikano Goikoetxea

230 musicians express their support for Raimundo el Canastro and claim that it is legitimate to criticize power through music

Among the signatories are Belako, Chill Mafia, Eñaut Elorrieta, Fermin Muguruza, Ibil Bedi, J Martina, ØDEI, Olaia Inziarte, Nøgen and Tatxers. A list of 237 musicians has been published.

2025-02-07

Ainhoa Mariezkurrena Etxabe

The Shadow Vagina

Here the lie reigns

Vagina Shadow(iko)

Group: The Mud Flowers.

The actors: Araitz Katarain, Janire Arrizabalaga and Izaro Bilbao.

Directed by: by Iraitz Lizarraga.

When: February 2nd.

In which: In the Usurbil Fire Room.

-------------------------------------------------------

Verse to... [+]

2025-02-07

Xabier Letona Biteri

Fascist Attacks in Lower Bidasoa and Devenir Europeo

Fascist, xenophobic or homophobic attacks are also on the rise in the Basque Country, and concern has spread here and there. The Bajo Bidasoa belongs to the areas affected by these attacks, where, specifically, most of the attacks and/or actions are carried out by the group... [+]

The University of Los Angeles makes available videos of the unpublished war of 36

Images of San Sebastián and other municipalities of Gipuzkoa can be seen on the university website.

2025-02-07

Aiaraldea

The Municipal Government of Amurrio has been surrendered the attachments of 1,700 citizens and agents in favor of the restoration of the subsidy of the Media Ayaraldea

Several media workers and partners attended the plenary of the City of Amurrio a week ago to denounce the elimination of the subsidy for the second year. The mayor, Txerra Molinuevo, gave no answer.

Presentation of the legislative proposal for the removal of elements with fascist symbology from the Monument to the Fallen and the creation of the interpretation center

The PSN, EH Meetup and Future Yes presented today with the signature of the parliamentary groups and will have the support to be approved.

2025-02-07

Gedar

The attacking teacher of the Eunate school in Borrería gets the students to leave

According to the IA of Pamplona, this teacher sexualized students and justified the violations. Last Friday they held a sit-in and had a collection of signatures in action to dismiss the teacher.

2025-02-07

Uriola.eus

Two men report homophobic attack in Bilbao

A group of four or five people were beaten as well as made homophobic insults.

2025-02-07

Euskal Irratiak

by Ximun Fuchs

"Because the Basque offenses are so insulting that we are not emotional cripples"

The company Le Tampographe Sardon has for sale the stamp box of 24 lashes. It is available online. It is the actress Ximun Fuchs who has made the selection work, since insults are a "work tool" for her.

2025-02-07

Olaia L. Garaialde

Some tools for mental health care in activism

Some activists have compiled the impatience of activists and created a guide to address them collectively. They have worked on issues such as stress, fear, frustration and fatigue.

Eguneraketa berriak daude