Society

Environment

Politics

Economy

Culture

Basque language

Feminism

Education

International

Opinion

wednesday 05 february 2025

Automatically translated from Basque, translation may contain errors. More information here.

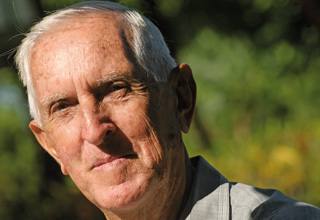

"I see Gernika every night on my home TV"

- The Cuban historian Arrozena tells you the news in Havana: “You have one, only one, living witness to the bombing of Guernica on the island. His name is Jorge Eduardo Elgezabal, and he lives in Cienfuegos. I don’t know anything else.” And negotiate the car, take the writer and painter José Enrike Urrutia Capeau as an assistant and go on an adventure of just 400 kilometers, hoping to find the assistant... He was also found, assisted by the Jesuits of Cienfuegos, in the town of Caonao.

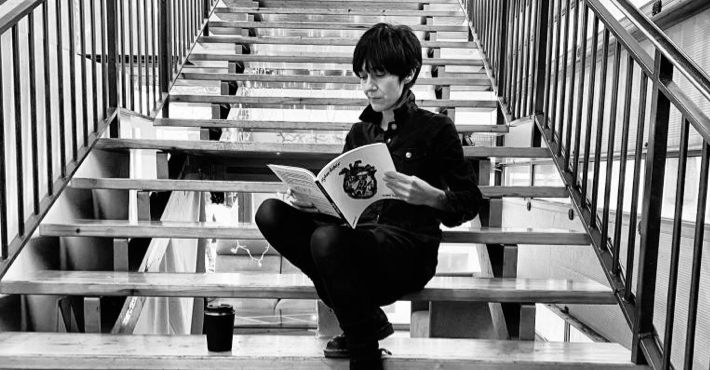

Zaldi Ero

We have you who were born, raised and alive in Cuba, but you were in Guernica that April 26, 1937, under the bomb...

I’ll explain it to you, even if it’s just a section, because I have it in the book I’m writing. My parents, my parents, my two siblings and all of us went to Spain in 1932. We went to Galicia, A Coruña, where my father was born. He was a blacksmith, well worked hard! That fucked him up. He did a great job, very important at the time. He loosened a lot of knots! But, you know, forging and hammering aren't easy friends, they're very violent. And, in poor health, the doctors promised him a colder country. We went to America first. We spent four years there. From there, to a small town in A Coruña – evidently because his father was from there – and before he came back to Cuba, his father wanted us to see his family and his country too; to visit him. And that’s how we got to Guernica in 1935. I was the youngest in the house, I was 10 years old. That's our story until then. Then there was the bombing, and that's it.

So you had a Guernica family on your father's side.

Yeah, but let me tell you another section of the book I've written. We saw reds in Guernica even before that day of bombing. In those two years we were hungry and cold. We were Cubans, we have a tropical climate here, we have hot bread every day, and there (both in Galicia and Gernika), the cold entered our bones. We were also very hungry. I remember eating meat once. Once upon a time! Our food was garbanos and loaves of bread. I’ll tell you more, and it’s true: our father used to go to the mountain, to the nearby fields, looking for some grass to give some taste to the soup that my mother made. To deceive ourselves, I think. It wasn't easy, then! You know what the saying is here: “It’s not easy!” but at that time, it wasn’t easy in Gernika either! Since I was a little girl in the house, I was the only one who went to bed at dusk with something in his belly. And not always! Our parents, and my brothers and sisters, came to bed with their guts. And don't even think about the Cuban family helping us. That party was blocked, that northern Spain, I mean. It was the war. And on April 26, 1937, German planes dropped bombs. The bombs fell that day, but they had sounded the alarm many times before, and every day we went to the shelter where they were. It was just a few blocks away from the house.

And the bombing...

The bombing? I remember it was a market day. I didn't think it was a terrible thing. The situation was of a certain nature. There was always a farmer who brought the domestic animal and swapped it for someone else, or sold it, or whatever. When the alarm went off, we rushed to the shelter. That day, they were serious, we entered the shelter as the bombs were falling. And next to us, the farmers, who were in the square. I think there were 600 of us going into those shelters, but that day there would be more than a thousand of us. I mean, it was market day, and the farmers in the area were also there, getting out. In my wake, we spent three days lying there.

Three days locked in the shelter?

At the shelter, yes, but that day, the 26th, we went out to see what was out there. And that was it, that was it, to see! Everything was broken. I've never seen anything like it in my life! People roaring, some crying, some holding each other, hugging each other. Looking for their children, in the grief of their relatives, wondering where their parents were, all screaming... What was that, then! Dead on the left side, all ages, dead animals too, body parts here and there, wounded as much as they want, fire... I have those memories, it wasn't a sweet thing, for the 10-year-old boy. Thankfully, my mother was by my side. He was holding me, protecting me. My brother, on the other hand, did not go to work that day, and that is why he went out unharmed, because the bombs broke the printing press where he worked; no one survived. I have no words to tell you what I saw there, what I'm seeing there now... I'll never forget it, I've got the smallest detail in it, and once I'm there, I'll never forget it. I walked from one side to the other after the bombing of Guernica, and everything was broken, shattered. Only the junta, the church of Andra Mari and the weapons factory were freed.

You were a 10-year-old boy.

And I've kept the memories of the 10-year-old boy, but my mother and my siblings had more. Unfortunately, they're dead. My mother said a lot of things. He said that when he went to see his father’s family, they spoke only in Basque and called his mother “model” and understood only that word. They didn't like the idea of one of their houses marrying the Galician. But soon after that they loved him by the law of the house, that they loved us. After all, they were good-hearted people. That's what my mother said. In a local newspaper my mother told me that we lived on Alzada Asylum Street, number 19. I'm going to read what my mother said to Juventud Rebelde here a long time ago: “Before the war began, we saw that the Jesuits were moving. The things of gold and silver began to unite, to melt for St. Ignatius of Loyola, to a certain appearance, although they were actually melting for Franco. But the abbot Eusebio Arronategi, and Domingo Iturrarán, pastor of the church of André Mari, opposed them...”. Her sister also counted the Gernika in the same magazine. “Guernica was threatened, many peoples legally. They started making five shelters, but when they started the attack, they were still unfinished. The only one was cement. The others were made of pine trunks. When the Germans dropped the bombs, the pine caught fire, and the people hidden inside died in it. It was Monday, the market day, I said, and we were at home when the alarm went off. That meant air strikes. We went to the portico, where the third shelter was. In the middle street there was another one in the street Don Tello. These were completely destroyed by the attack. The people inside died.” My sister said that the shelter we went to was full of people, more than 700 people, and that we had water all the way up to our ankles. Outside, they put sandbags, dry sand, and when the bombs exploded, the sand went into the shelter. When we didn't drown! There was no oxygen for everyone, all piled up there, in bundles. General Queipo de Llano said that Guernica would break everything, and the Guernicans were prepared in any way they could. After the bombing, we went through the mountain to Busturia, where we were shot by Franco’s soldiers. There, they gave us blankets, clothes... We were all muddy and afraid in the air! My sister told me, and I remember something.

They say that the memory is always there, you can't get away...

Oh, yeah, yeah. It is enough to explain on television Iraq, Afghanistan or the place in question, in order to evoke the Gernika. I said it once, and then the reporter put it in the paper: “I watch Guernica on TV every night.” I see people running from there to here and from here to there, running, and I put myself in their skin, even unintentionally. I’m also saying in the book I’m writing that twenty years after returning to Cuba, our Kiro family lived dancing every time they heard the sound of the siren, or the bells ringing, or the sound of alarm. It's not easy, no! Much has been written about...

It's also the subject of your book, be it.

Yes, of course! I say that this was an attempt, which was designed by the German dome. They sent the legion of condors. They bombed Guernica and studied how civilians reacted. It was a Nazi experiment to see the response of women, men and children! The Condor legion had a camp in Vitoria-Gasteiz. They had new generation aircraft there, and they needed to test them, before World War II began, on the brink of that great war. Gernika was a war crime, it has no other name! People had no way to protect themselves. As I read here or there, a general of the fascists said: “We’re going to throw bombs at the young people of Gernika.” You have to say it later! That general must have been sick to say that. The American journalist Herbert Matthews described the bombing of Guernica as a prototype of “totalitarian bombing”, and according to Professor Ludger Mees – you will know the historian, Vice-Chancellor of the University of the Basque Country – Guernica was “a bank of tests of the strategies of the Nazi army, of its technologies, of its planes, of its bombs”. There is no doubt, then. Hitler used the attack for this, to see how this great military machine that he would later use was working, to prepare for the war.

Liburua

“Kubara itzuli ginela kontatzen dut eta hor amaitzen da liburua. Harrezkerokoaz idaztea ez zitzaidan inportantea iruditu. Baina bai, hemen ere banuke zer kontatua… Iraultzaren gaineko kapitulua eransteko esan didate, eta horrek atzeratu du liburua argitaratzea. Gernika darama izenburuan, jakina”.

Nortasun agiria

Jorge Eduardo Elgezabal Martinez (Cienfuegos, Kuba, 1925). Errigoitikoa zuen aita, Kasimiro Elgezabal Apraiz, eta galiziarra ama, Maria Luisa Martinez Vega, Santa Marta Ortigueirakoa. Kuban ezagutu zuten elkar, bertan ezkondu. Hiru seme-alaba izan zituzten, Luisa, Kasimiro eta Jorge Eduardo, bizirik irauten duen bakarra. Galizian ziren 1932an, Kubako egoera politiko makurraren ondorioz, Gerardo Machadoren diktaduratik ihesi. Galiziatik Euskal Herrira etorri ziren atzera Cienfuegosera itzuli baino lehen, Errigoitiko familia ezagutzera. Horrela harrapatu zituen Gernikako bonbardaketak. Sarraskiaren lekuko izan ziren. Aldi hura paperean jarria du Jorge Eduardo Elgezabalek, liburu idatzia, azken ukituen zain.

Most read

Using Matomo

#1

#2

#3

#4

Mikel Garcia Idiakez

#5

Axier Lopez

You are interested in the channel: Gernika 1937

2024-04-26

Urko Apaolaza Avila

One more year the mermaids in Gernika, with the Palestinian people and the Artisans of Peace

This Friday is 87 years since the fascist aircraft bombed and massacred Gernika on 26 April 1937. Like every year, institutions and social partners have organised many activities. Commissioning of the siren section, walk and factory of Astra.

2023-05-09

Urko Apaolaza Avila

Forgetting yesterday’s crimes, how can we avoid today’s wars?

Beyond the bombing of Gernika, Germany is barely aware of the participation of the Condor Legion in the massacre of the population during the 1936 War. Journalist Carmela Negrete has told this lack of memory in Context magazine. Without settling such debts, how will we avoid the... [+]

2023-04-27

Urko Apaolaza Avila

The crimes of the Condor Legion forgotten also in Germany

In Gernika there have been commemorative acts of the 1937 bombing, and a dispute arises after statements by Minister Bolaños of the Spanish Government: "It is an honour to be here to represent the legitimate government of the Republic that attacked with the bombing." In Germany,... [+]

2023-04-25

Gorka Peñagarikano Goikoetxea

Gernika bombings 86 years

Alternative programme to out-of-focus shelling

On 25 April, on the eve of the anniversary of the massacre, journalist Igor Meltxor will present in Astra the book 'Cabacas'. In the Elai Txiki room you can see an exhibition of images of the Civil War selected by journalist Iñaki Berazadi.

2023-04-19

Urko Apaolaza Avila

Published the book on the bombing of the Condor Legion in Munitibar in 1937

Munitibar 26/04/1937: Chronicle of an air strike and public presentation on Sunday. On 26 April 1937, the Condor Legion attacked the inhabitants of Munitibar. In the afternoon of the same day he was prologue to the massacre in Gernika.

2022-09-26

ARGIA

Luis Iriondo dies at age 100, one of the last witnesses of the Gernika bombing

He died on Monday in Gernika, according to municipal sources. He was 14 years old when his people were bombed and he had to take refuge in a shelter. In his book El chico de Guernica reported the experience.

2022-04-26

ARGIA

Emilio Aperribai, survivor of the Gernika bombing

"Just like the German government asked for forgiveness, what the Spanish government should do is ask for it as well."

Emilio APERRIBAI was an 8-month-old boy when they bombed Gernika. The mother held her in her arms to a house in Lumo and managed to survive. He and his daughter Monica wrote a letter last year to the Spanish Government and transferred it through the lehendakari, Iñigo Urkullu... [+]

2022-04-25

Urko Apaolaza Avila

The cries of the Gernika bombing, alive after 85 years

The City of Gernika and the local associations have organised several events to recall the massacre of 85 years ago, which began on 26 April.

2022-04-21

Urko Apaolaza Avila

Sare will travel the route of the railroad refounded by Republican prisoners from Gernika to Bermeo

As part of the commemorative events of the 85th anniversary of the bombing of Gernika, Sare de Gernika-Lumo has completed the memory journey that will continue this Saturday following the railway line from Gernika to Bermeo.

2022-04-20

ARGIA

On 26 April, anti-war mobilizations will be held in the capitals of Hego Euskal Herria

On 26 April, coinciding with the 85th anniversary of the Gernika bombing, concentrations will be held in the capitals of Hego Euskal Herria. Some municipalities may also make their own calls.

2021-04-26

Urko Apaolaza Avila

They present an advance video on the occasion of the 45th anniversary of the Gernika Commission

On the same day that Gernika was bombed, the first public statement by the Gernika Council was made on 26 April, 45 years ago. It has since become an important instrument for maintaining the memory of the 1937 massacre. A video is being made and progress has been made on the... [+]

2021-04-13

Urko Apaolaza Avila

Unknown Photos of the War of 1936

Koch, the rear shadow of the smoke

In the photographic collections given by the relatives of Sigfrido Koch Bengoechea to the Museum of San Telmo in San Sebastián, there are photographs never seen so far. In the dead bodies, in the perfect order of aircraft and missiles, and in the skeletons of calcined... [+]

Eguneraketa berriak daude