We’ll take you by song when we remember you

- He grew up singing, and he lived singing. He sang his sorrows as he fled. He won a lot of what he had by singing. They sang to him as he spread his dust.And even the new generations, unable to do otherwise, remember Mikel Laboa singing his songs.

The musician died, but his work is still alive. “Many of Mikel’s songs have had an oral transmission, and as a result they have survived, and I think they will survive,” says Eneko Aranzasti, a musician and member of Bidehuts. Mikel Laboa is integrated into the collective memory, but his work is not yet finished. It is growing over time, since it has been subjected to an infinite number of interpretations, also by eleven artists. However, versions have been made to many well-known musicians, and Mikel Laboa did the same with Atauhalpa Yupanqui, Xabier Lete and others in his time. But the case of the San Sebastián is different, since it is a very widespread trend to make versions of it. The reason, according to journalist Julen Subarte, is that Laboa’s music “has become a popular song”.

A bridge between generations

Even though it has become a popular song, Laboa is still an artist “in the vanguard well rooted in tradition,” says Subart. To achieve this, he maintained a constant exchange with the new generations and young musicians. It is not surprising, then, that he collaborated with several groups of the time. With Fermin Muguruza and Duts he included his voice in the song Castillos, in the band Kortatu’s Hundredfold, in the last album Iqharaturic by Nago Roxa, or in the work Nomadas TX by Equilibrio TX, among others.

These exchanges have given him many versions and tributes by the groups of the moment. “Without ignoring his style, Laboa was always evolving, which allowed him to be always up-to-date. This feeling was awakened in the new generations,” says Ibon Rodríguez, a member of Eten’s team. But “if you want to take Mikel as an example, you have to keep on revolutionizing him without miticizing or petrifying his work,” he says. In the Cherokee album released in 1990, you can see this dump. Many significant bands brought Laboa's work to rock. Twenty years later, the same thing has happened, and the new generations continue to revolutionize the work of the Labo, such as the Chinaurías (see the chart on the next page).

The universality of

Laboa also reached out to foreign artists: “For the most part, they have been gestures of gratitude. It involves the political situation of the Basque Country, the Basque language and other nuances, as well as the consideration of Laboa as an icon”, says Rodríguez. The Palestinian singer Rim Banna has collaborated with the group Arramazka in a new adapted version of Gure palabras; the group Proyecto Swing de Toledo (Spain) plays Txoria txori in the style of jazz and swing; and the same song was sung by Joan Baez at the concert he offered in Bilbao in 1988, as Pablo Milanes has done in the performances of the Basque Country; Cor Ciudad Vasco de Barcelona sang the same song in the theater Nacha Biga in 2009.

To achieve this universal character, Subart takes as an argument what Steve Reich said. “The more local, the more universal. Laboa was an impatient musician who combined many styles. But he used this combination to get his own flow. When you hear the Laboa you don’t think about the fusion of styles, you think about the extraordinary musician, the musician who took good care of his flow, but also the musician who didn’t settle for it. I think it was universal.”

Not just in music

And the Laboa has also been subjected to revisions in other disciplines. According to the pianist Iñaki Salvador, this is due to the fact that Laboa sought inspiration in numerous artistic disciplines. “The painters, sculptors, dancers or musicians who have been involved in his work have done nothing but a modest ‘deconstruction’ of the complex architecture of Laboa’s work.” For example, the Italian dancer

Manuela Carretta has created a flamenco dance with the song Haika Umea; the group of Zorón also dances flamenco with the music of Laboa, as well as the dance group Amilotx or Jon Ugarriza. The sculptor Koldobika Jauregi gave an exhibition at the Ekain Gallery in San Sebastián to the wild air of the shepherds of Laboa and Alcierürüküko; the artist Juan Gorriti has also taken the lead in making two sculptures, not to mention the painter José Luis Zumeta.

Various competitions have also been organized under the theme of Mikel Laboa, such as the sculpture competition held in Usurbil and the writing, image and music awards organized by the UPV/EHU. He said he did it more than once. At the 2008 Biscay Championships, when Laboa had just died, Igor Elortza threw the prison verses with the melody of the Estrellas powder; Maialen Lujanbio also sang the first notes of a March with the melody of several verses at the 2009 Basque Country Grand Prix, including the farewell after wearing the hat.

The shadow of the myth

When the Labo is mentioned, the listener comes to mind as Bird Bird, Baga biga higa, O Pello Pello, Dust of the Stars... The cause of this may be, on the one hand, the ignorance of his work; on the other hand, the mythification of the figure of Laboa. “The myth overshadows the musician Laboa, and many times we stay with that image, discarding the musical part a little. It seems to me that we do not value his music as a whole,” says Julen Subarte.

For what reason? “Because we don’t know about the work; because we stop with the mythical songs; because we haven’t immersed ourselves enough in its music; because it is also the avant-garde and that often intimidates the listener... After all, because Laboa’s work demands effort from the listener, and music has this hedonistic point for many: to party, to sing at dinners...”.

All these possible scenarios are proposed by Subart trying to understand the repetition of eternal songs. These songs, moreover, are not the most popular, “they are the only ones known,” according to Rodríguez. However, it is clear that many of these songs have also managed to be part of the Basque identity, which is why they have been chosen to make versions. In any case, Iñaki Salvador foresees that with time justice will be done, “and with more wisdom the integrity of what the Laboa has created will be valued.” In

any case, the greatest homage has been made, since his songs have already become those of the people.

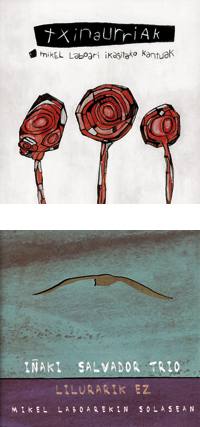

Lilurarik ez, Iñaki Salvador

1985ean argitaratu zuen 6 diskotik azken lanera arte Iñaki Salvador alboan izan zuen Mikel Laboak. “Sortze prozesuan aske uzten gintuen, baina berak nahi zuen norabidean. Musikari gutxik lortzen dute oreka hori” dio Salvadorrek. Orain Laboaren gidaritzarik gabe aritu da, eta Lilurarik ez bere azken lanean jazzera ekarri du, 1992an Zilbor hestea diskoan egin zuen bezala. Disko hau omenezko lana dela dio, “berarekin berriz jotzea bezala izan da, baina bera gabe”.

Jazza eta kanta herrikoiak uztartzeak on egiten die bi esparruei, Salvadorren ustez. “Gehiengoarentzat laguntza gisakoa da era honetako fusioak egitea, doinu herrikoiak nahasten baitira entzuteko zailagoak diren elementuekin”. Horrelako esperientziak ez dira berriak, hala ere. “Jazz musikariek historikoki ‘standard’-ak jo dituzte, hau da, abiapuntutzat kanta bat hartu, eta horren gainean inprobisatu dute. Eta nik ere beste hainbeste egin dut. Mikelen kantak joz, inpultso horri jarraitu besterik ez baitut egiten”.

Txinaurriak, Hainbaten artean

“Anarik denbora zeraman Antzinako bihotz zuzenean jotzen, eta Lisabök Xoriek 17 diskoan Orduan abestian jardun zuen. Garai horretan hasi ginen ideiarekin bueltaka”, dio Asier Zulueta Bidehutseko kideak Txinaurriak diskoaren genesiari buruz, “baina Laboa zendu zelarik, dena utzi genuen harik eta familiak, jakitun, aurrera egiteko esan zigun arte”. Donostiako Antigua auzoan egin zitzaion omenaldirekin gauzatzen hasi zen bilduma. Azkenerako hemeretzi taldek osatu dute Txinaurriak lana, bi LP eta bi CDk osatutakoa. Besteak beste, Ruper Ordorika, Audience, Mursego, Anari, Berri Txarrak, Xabier Montoia, Willis Drummond, Zura, Gora Japon edo Ama Say-k hartu dute parte.

“Mikelek eta bere inguruan zebiltzan guztiek emandakoa eskertzeko aukera bezala planteatu genuen diskoa”, dio Karlos Osinaga Bidehutseko kide eta musikariak. “Hasieran irudi eta testuak egiteko izen batzuk etorri zitzaizkigun burura: Zumeta, Atxaga, Sarrionandia... baina kantekin bezala, dena geuk egitea erabaki genuen”. Ramon M. Zabalegi arduratu da irudiaz, eta Martxel Mariskal liburuxkako testuez. “Txinaurriak diskoan badira Laboaren oinordeko izan daitezkeen hainbat artista: musikari ipurterreak, etengabeko bilaketan murgilduta daudenak, ahots propioa izan nahi dutenak, idazteko grina dutenak...”, dio Julen Azpitartek. Maisuari omenaldia egiteko, diskoa abenduaren 1ean argitaratu da, Mikel Laboa zendu zen data berean.

We learned this week that the Court of Getxo has closed the case of 4-year-old children from the Europa School. This leads us to ask: are the judicial, police, etc. authorities prepared to respond to the children’s requests? Are our children really protected when they are... [+]

Gabonetako argiak pizteko ekitaldia espainolez egin izanak, Irungo euskaldunak haserretzeaz harago, Aski Da! mugimendua abiatu zuen: herriko 40 elkarteren indarrak batuta, Irungo udal gobernuarekin bildu dira orain, alkatea eta Euskara zinegotzia tarteko, herriko eragileak... [+]

Irailaren 9ra gibelatu dute Kanboko kontseiluan gertatu kalapiten harira, hiru auzipetuen epaiketa. 2024eko apirilean Kanboko kontseilu denboran Marienia ez hunki kolektiboko kideek burutu zuten ekintzan, Christian Devèze auzapeza erori zen bultzada batean. Hautetsien... [+]

_2.jpg)