"Medicine is my fool"

- I went to the doctor sane and went out with a headache. How to make the words received by ear not lose grace on paper? Will the frenadol be enough?

You're the son of the bar...

Born in the bar of the Landes. That's what I owe the character to. After the war, ours was a bar that worked well, a lot of people came up from the surrounding area, and when my parents left the bar, we had 65 fixed guests who made their daily meals there despite going home to sleep. Later, I heard Imanol Lazkano say that this was the university of bertsolaris in the Azpeitia area. I drank from that sauce all the time and that's when I learned how to deal with it, how to deal with it and how to play the horn. It should not be forgotten that both in the bar and in medicine work is done with people. Both the doctor and the one behind the bar have to look at who comes through the door, how he is dressed, whether he is lame or not, what step he takes, what face... It’s curious, both in the bar and in the doctor’s, we are not always what we are, we have very different behaviors.

Then you would have been different. It would have been unusual to go to study abroad at the age of 11.

It was not unusual, and besides, even though I understood everything in Spanish, I was very clumsy talking. But I went to Pamplona, where no one knew Basque. I finished high school at the age of 11 and stayed there until I was 18. When I was there my father often asked me what I should study, and since he was a farmer, and I liked the cattle world, I told him that I would become a veterinarian. One day he told me plainly: “Look, Julian, if you go to a house to see a patient, they’ll take you to the kitchen in the worst case, if you go as a veterinarian, to the best, in the stable!” That was enough to convince me.

They say you spent the second and third years of your career operating on dead people every day.

If you don't work with the dead, you can't learn the trade fundamentally. It served us to learn anatomy in detail, and there are not enough doctors who do not dominate anatomy. For two years, for an hour every day, it was time to operate a dead body, a different body part every day. We operated on the section where he was going, and we kept the corpse there again, knowing that the corpses, like ham, are preserved with formalin. The ambulances of the war were not claimed by anyone and we were dealing with their bodies. Anyone who reads this will think I was a savage, but then that was the learning process, and thanks to that I learned that before every operation, you need to be clear about where you are, what you're doing, and what you're going to do.

What is your relationship to death today?

I estimate that I have undergone 40,000 surgeries in my life, and fortunately, no one has died in my hands. That's terrible luck. But to go from Zarautz to Azpeitia, I have to go through Zestoa, and when I get to the cemetery, I always look the other way. I've got the trail nailed to the inside, and I can't even see the dead. When I am asked if I will go away because of such a death, I always say that I will pray from here, otherwise I will shed tears. I've had a hard heart, but it's softening me. I try to get rid of feelings in my medical work, but in my circle of friends, I'm as sensitive as a 10-year-old boy.

Is it possible to have a hard or soft heart to completely separate work from the rest? Is it possible to circumvent this doubt that eats your insides?

It's cost me a lot. I have often been unable to sleep with those I have recently operated on at the clinic. There is always worry. I have visited the clinic once or twice, at least to attend to the patient, and I would have gone more times if they had not laughed at me. Once, I remember, when I went to a seriously ill patient, caught him asleep, and woke him up, he said to me, “You are Don Julian, aren’t you? Am I still living?” My stomach turned around. On another occasion, I didn’t feel comfortable coming home from an operation, and as I was walking around in the night unable to collect my eyes, I picked up the phone and called my boss to review the operation. Reviewing it, making sure we operated well, the boss told me “now let it be what God wants it to be.” But knowing that not everything depends on us does not diminish our responsibility and responsibility. Enter the operation with a smile and a sense of humor, and the patient “are you laughing? Well, I’ve come to leave two little children at home, when he says, “Hey, you get your legs on the floor right away.

Ever since you were a doctor, I've read to you that what you've gained in science has been lost in humanity.

Clearly and unequivocally. The patient is a person. It sounds like Pernando's truth, but don't think it's true at all. A recently deceased medical friend wrote me a letter a long time ago from Germany saying that the patients there were a number. If the doctors' shift there ended in the middle of the operation, a change of equipment was made, and at the end the patient did not even know who had operated. Even when the patient had to stay in the hospital for a week, a different doctor would visit him every day. I've never liked that. I believe that medicine is based on the relationship and that this mutual knowledge only brings benefits. If the names and surnames on both sides are deleted, everything is more complicated, and I believe that the proliferation of complaints against doctors is directly related to this.

It is part of humanity to make the patient in his own language. You have done this to your patients from the beginning.

If you do it to a patient in their own language, you are assured of half the success. A medical friend always says that he started with a patient and responded as best he could. He knew that he was Basque, he did it in Basque, and the patient changed not only his face, but also his response! That's all there is to it, isn't it?

Do you always have to tell the patient the truth?

Don't even think about it. Recently I learned of the case of a woman who was not in my hands. He had cancer, he was very ill, and they thought to tell him the truth. He died instantly. I learned in my career that a doctor rarely heals, relieves pain quite a bit, and always needs to be comforted. When the patient notices that he is losing his appetite, losing weight, that everyone looks at him with compassion and earnestness, he knows that something is happening to him, but he does not want the whole truth. I always joke with patients who tell me, “Better dead than alive.” Once you get out of the office, I order you to come back in, and I forgot something... and I ask you to lie down on the bed of your hands. That’s when they are surprised and alarmed, they ask me “what do you have to do with me?” and I tell them that I have a small injection to kill. No one wants to, we all want to live. That’s why the patient’s decline often begins as soon as the truth is known. We have no right to prolong the agony, but as long as possible, the patient must be encouraged.

What is the relationship between the Basques and the disease?

It's hard for us to say we're sick, we'd rather hide it. At the first visit you will start to make records and many patients will tell you that they have never been sick. He lifts his head, asks again, and the next one adds that he has had a meat cut, that he is operated from the cataracts, this, that and that. For example, when I was a kid, we had a lot of TB in our country, a lot of people died, but nobody says they have passed TB. Even today, when I find clues with X-rays, many respond to me “ah, yes, I was forgotten”. That’s why people have come to the consultation with fear for years. That’s where phrases like “the best way not to get sick is not to go to the doctor.” Why do you think some people prefer to go to the curandero? People know that, at most, you're going to order them to put a couple of herbs, and that the herbs don't kill you. The doctor, on the other hand, can give a strong drug, and if he kills it, what? A priest who knew a lot about this did not say in vain that the Basques were “deaf, hard, and stubborn.”

That would have been the opinion of the social security inspector who called you in for an account.

This was in the recently expanded consultation in Azpeitia. At that time, I saw a lot of 60-year-olds coming to the market with sticks. “It’s not possible, we don’t have good things,” I thought to myself. I turned the subject around two times, and immediately realized that the explanation was related to the orography. Errezil is a very steep town and this develops its own ailments. In our country, knowing that there was a way to charge four cents for disability, I began to fill out paperwork for everyone. One with a discomfort in the knee, the other with a tired heart, the urlia with a high tension... I used to set up truths. I knew the social security inspector at the time and one day I got his call. “Julian, what’s going on here? We know you have a lot of friends around Azpeitia but don’t play so many roles, you’ll ruin the government if you don’t!” I threatened to put them to work a couple of days in a farm in Errezil to see what it really was, and that's when it all ended.

In addition to being deaf, hard and stubborn, the Basque has had a reputation as a jale and drinker. Now, on the other hand, we seem obsessed with nutritional issues.

Too much of it. We are often accused of thinking only about food and drink, but beware, it is not even beautiful to be hungry, everyone is petral-petral. We've become obsessed with weight, but we've got it wrong. The magazines have confronted us, and there are many lies in the magazines. We should live the food and drink in a much more healthy and rational way. When I started, there were a lot of alcoholics in our country, but luckily, the number has decreased drastically. For what reason? Because we understand that if you eat well, you can live bapo by drinking less. Here it has been customary to go to the mountains, to football, to the bulls... anywhere, always with the old man, which is bad. Drinking alcohol in the empty stomach does a tremendous amount of damage. That’s why I used to tell customers who came to the bar as children to eat and drink, and those who come to the consultation to eat and drink but both at the same time! Imagine, as a beginner I remember visiting a lady with cirrhosis who loved wine. I told him not to taste wine and that I would visit him often. Shortly after, they called me saying that it was done in full, and when I went to ask him for the account, that he had not eaten a word, that he did not give it to the wine, that now he drank the Xerez!

Years have passed since then, but at the age of 74 you still work in the Azpeitia consultation. It will be true that the work is health...

Medicine is my fool. I ask many retirees how they live, and more than one confesses to me that at first he had a very bad time, to the point of crying impatiently. I think I'd better get on with it, and as long as I like it, go ahead. The time will come to leave it, and when it comes, leave it and you’re done. However, when I see that my work deprives another of food, I will leave it. I have seen this before, and young colleagues cannot be bothered. They deserve all the respect and support.

Jarritako kondenak barkatzearen truke, armadara batu da preso andana. Azken urtean, errekrutatze-legeak gogortu ditu gobernuak.

Arma nuklearren produkzioarekin, mantentze lanekin eta modernizazioarekin loturak dituzten hainbat enpresa aztertu dituzte, eta horien artean agertzen dira BBVA, Santander bankua eta SEPI.

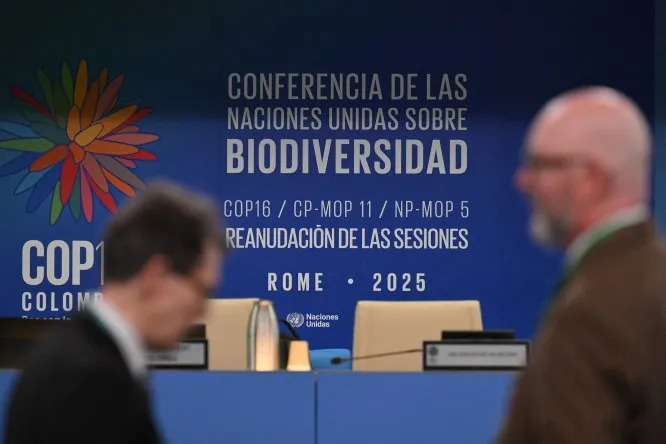

Iazko urriko bileran lortu ez zuten akordioa erdiestea espero dute COP16ko parte-hartzaileek, eta ostegun honetan dute gailurraren azken eguna. 2030. urtea bitartean, bioaniztasunaren alde 200.000 milioi dolar bideratzeko engaiamendua hartu zuten 2022ko COP15 gailurrean, eta... [+]

570.000 familiek euren haurren ikasgeletako hizkuntza nagusia zein izango den bozkatzeko aukera dute martxoaren 4ra arte: gaztelera edo katalana. Garikoitz Knörr filologoaren eta euskara irakaslearen arabera, kontsultak "ezbaian" jartzen du katalanaren... [+]

Martxoaren 29an ospatuko dute irratiaren 40. urteurrena, musika, literatura eta tailerrak bilduko dituen Txapa Egunarekin.

"Ipar Euskal Herria gaztez odolusten ari da". Sail berriak sortu goi-mailako ikasketetan, etxebizitza sozialak egin gazteentzat edo aisialdia euskaraz bermatu… Hamabost proposamen konkretu egin ditu Xuti Gazte ezker abertzaleko gazte antolakundeak.

Uribe Kosta BHI institutuko hainbat ikaslek salatu duenez, mezu "iraingarriak, matxistak eta homofoboak" jaso dituzte Batxilergoko beste ikaskide batzuengandik. Horrez gain, gaineratu dute mezuak irakasle bati ere bidali dizkiotela eta beste ikasle batzuen... [+]

Urruña, 1750eko martxoaren 1a. Herriko hainbat emakumek kaleak hartu zituzten Frantziako Gobernuak ezarritako tabakoaren gaineko zergaren aurka protesta egiteko. Gobernuak matxinada itzaltzeko armada bidaltzea erabaki zuen, zehazki, Arloneko destakamentu bat. Militarrek... [+]

Aiaraldeko hainbat irakaslek mezua igorri diete ikasleen guraso eta familiei, dagoen informazio zurrunbiloan, grebarako arrazoiak modu pertsonalean azaltzeak euren borroka eta lanuztea hobeto ulertzeko balioko dielakoan.

Biologian doktorea, CESIC Zientzia Ikerketen Kontseilu Nagusiko ikerlaria eta Madrilgo Rey Juan Carlos unibertsitateko irakaslea, Fernando Valladares (Mar del Plata, 1965) klima aldaketa eta ingurumen gaietan Espainiako Estatuko ahots kritiko ezagunenetako bat da. Urteak... [+]

Ezpatak, labanak, kaskoak, fusilak, pistolak, kanoiak, munizioak, lehergailuak, uniformeak, armadurak, ezkutuak, babesak, zaldunak, hegazkinak eta tankeak. Han eta hemen, bada jende klase bat historia militarrarekin liluratuta dagoena. Gehien-gehienak, historia-zaleak izaten... [+]

Martxoaren 8a hurbiltzen ari zaigu, eta urtero bezala, instituzioek haien diskurtsoak berdintasun politika eta feminismoz josten dituzte, eta enpresek borroka egun hau “emazteen egunera” murrizten dute, emakumeei bideratutako merkatu estereotipatu oso bati bidea... [+]

Euskal hezkuntza sistemaren itunpeko eskolen gainkontzertazioa eta zentro pribatuen umeak hartzeko gaitasuna beherakada demografikoari eta biztanleriaren klase osaketari egokitu behar dira.

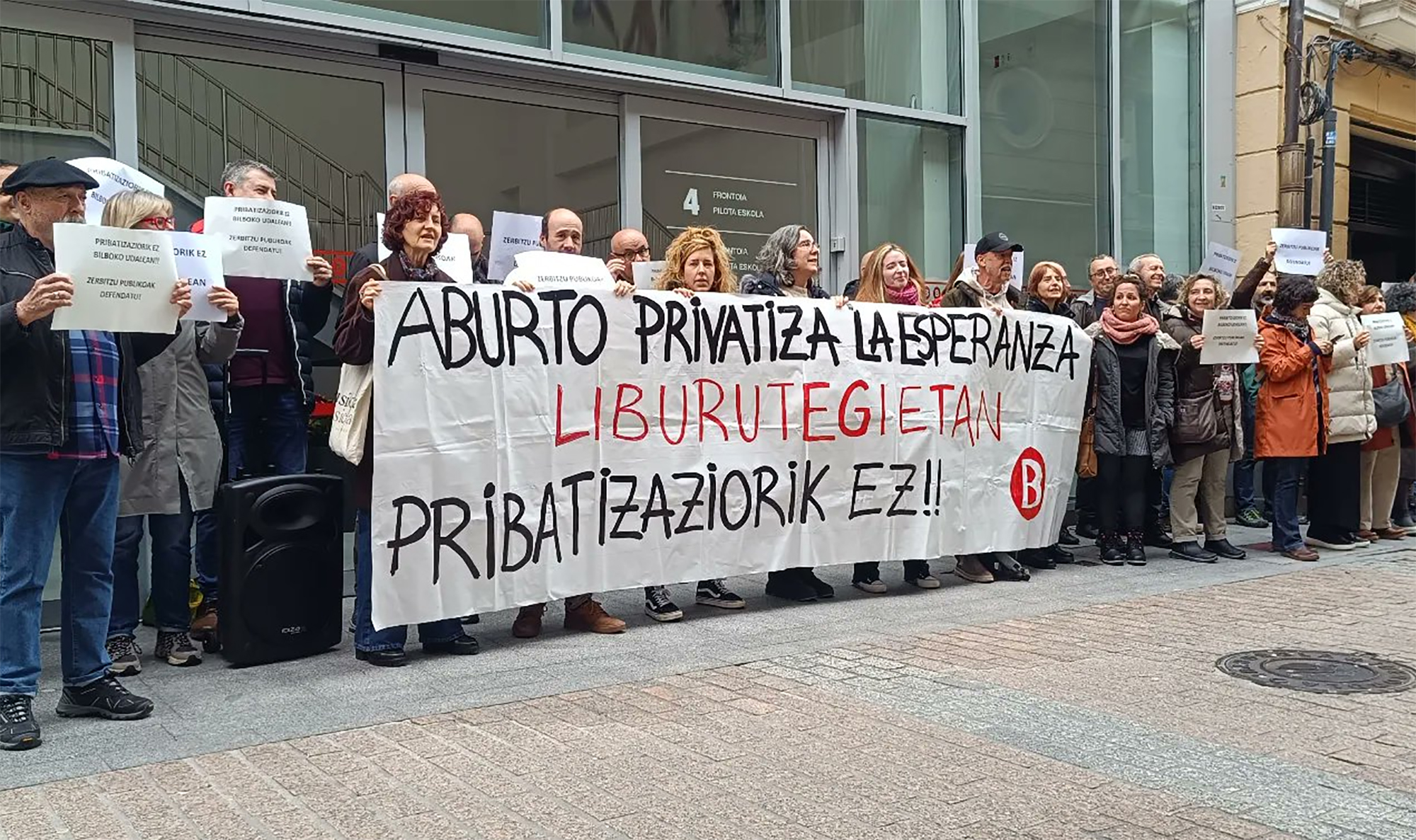

Bilboko Udalak zerbitzu publikoak pribatizatzen jarraitzen duela salatu du Bilboko Liburuzainen kolektiboak, besteak beste, kulturari loturiko zerbitzuak. Horren harira, mahai-ingurua antolatu dute martxoaren 3an Bidebarrieta liburutegian, Kulturaren pribatizazioa izenburupean.

Martxoaren 1ean ospatuko du NNPEK-k urteurrena argazki erakusketa eta txalaparta ikuskizun batekin.