Lying with ecology and health

- Arguments related to ecology and health are widely used in advertising. We are already accustomed to hearing that a polluting company is acting in favor of the environment, or that a common food is doing a great favor to health. Measures have been taken in the last year against these inappropriate messages both in Europe and in Spain, but things have not improved too much, as some voices denounce.

Isidro Jiménez is a member of Ecologistas en Acción in Madrid. Advertising is one of the areas of work that dedicates most of its militancy hours to the project Consume hasta morir (Consume until death). It begins with a strong statement: “Most advertising is illegal because it hides essential information from consumers.” The statement is valid for the entire advertiser sector, and also, of course, for those who use the variables “ecology” and “health” in their ads.

Advertisers have a different opinion. The Spanish Association of Advertisers, when we announced to him that some of the things that would be said about them in this report would not be sweet presumptions, gave us the answer from the guide book of those responsible for communication: the members of the association strictly comply with the legislation and the whole sector should not be judged by a few rare exceptions.

Autocontrol is the name of the body created specifically for the self-regulation of the advertising industry – France also owns it: BVP, Office of Advertising Control–. Autocontrol reported last year’s balance in March, and the title makes it clear that they are satisfied with themselves: Spanish advertising reduces its ya baja conflictividad. Few problems, less and less. According to the data provided in the report, in 2009, 192 claims were resolved, 29 fewer than in the previous year. Considering that thousands of ads are delivered, they don’t seem like alarming amounts. How do you marry that to what Isidro Jiménez said?

Normal foods can’t cure us

Apress release sent by the AUC (Association of Audiovisual Users) in July last year gave us the first clue on this issue. “Health-related arguments in food advertising are abused,” they said. The President of the Association, Alejandro Perales, reasoned this statement as follows: “They want to convince us that a certain brand of milk is not, at this point, pure milk, but a ‘source of life’, or ‘great for boosting the immune system’, or ...” The AUC has been saying for years that the use of arguments of this kind is not allowed, because it is not possible to convince people that a common food has therapeutic properties, or is suitable for health prevention.

Such arguments, according to Perales, are thrown out without evidence by advertisers, despite the fact that Spanish legislation prohibits them from doing so: “They do not show the scientific study that demonstrates what has been said. And sometimes the ingredient they refer to does not have the qualities they want to attribute to it, and sometimes the properties of the ingredient are really beneficial, but the amount of it is not enough to have a positive effect on the recipient.” Another behavior of advertisers, also prohibited by law, is the

general mention of health benefits without association with a specific ingredient or characteristic of the food. That a baby food is “100% healthy”, that a dairy product serves to prevent certain pathologies, that a chocolate bar “helps to grow”, that a yogurt is “the perfect ally to take care of the bones”, that a brand of milk is “the healthiest and most natural”... The AUC has filed claims against many such advertisements with Autocontrol and has managed to remove such advertising on several occasions.

Sterile legislation

The legislation that aims to prevent the abuse of advertisers has been in force in Spain for almost fifteen years, but Perales says it has failed because it has not been able to implement it correctly in practice. “Among other things, the agreements reached by the authorities with the industry have done a lot of damage, according to which it cannot be said that a product contributes to your natural defenses, but it does contribute to your defenses, for example.” AUC’s complaint is that advertisers ultimately get the same result by saying one thing or another. “It was established what could not be said, but anything out of it was possible.” For Perales, another factor

that has allowed the use of many inappropriate messages in advertising has been the distinction established by Autocontrol itself: on the one hand there are health arguments and on the other there are health arguments. Those in the first group are allowed, those in the second group are not allowed. “This rule has given advertisers a lot of freedom to say what they wanted,” the AUC tells us, “It would be a health argument to say that something serves to cure or alleviate a particular ailment, while health arguments have to do with well-being in general terms, from which anything can be included, because the creators know perfectly how to measure what they say.” In the end, despite the rules, the consumer receives the same message that is forbidden.

The situation was so serious that, as in the Spanish State throughout the world, the European Union adopted a regulation in 2006. According to this, all advertisers are obliged to inform the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) of the argument they wish to use in their advertisement and the approval must be given by EFSA. Accepted arguments are included in a positive list, and only those from that list can be used. The problem is that the deadline for creating a positive list has been increasing, while advertisers have continued to use the old criteria.

Finally, the EFSA published its first positive list about a month ago. It is a positive step, in the opinion of Alejandro Perales, but the problems do not end here. “The regulation is a step forward as it establishes a much more precise framework, but it remains to be seen whether the list really helps to order this chaos, as advertisers are looking for ways to keep saying things that are not entirely clear.” For the time being, many companies have chosen not to submit the announcement to EFSA unless they are sure that it does not meet the requirements. In the event of EFSA’s refusal, it is not possible to use this publicity, but as long as they do not receive the refusal, they are in an ambiguous area and have the opportunity to continue spreading their slogans.

When the energy and automotive industries are “green”

Something similar happens with advertising that uses the environment as an argument, but in this case the reaction, in the Spanish State, has been a code of self-regulation. The measure has not been adopted by the companies themselves, but by the Ministry of the Environment, and for the time being it affects the energy and automotive sectors.

Ministry officials noted that the use of environmental arguments was on the rise and was not always done in the most appropriate way. In the end, they were all “green.” Supposing the need to take measures, they opted for the self-regulation code and managed to include in it all the important companies of the aforementioned sectors, 22 in total. After obtaining the consent of all parties, the code came into force last September.

The goal is precision. Anyone who claims to be in favour of the environment will have to explain the reason for this with verifiable arguments. Thus, the self-regulation code does not allow, for example, general slogans such as power and ecology, which have become common in the advertisements of some car brands. It is not possible to mention ecology, environment, sustainability, etc. without providing data. In most cases, these data are comparative. If you want to say that the car you want to sell consumes little, you will need to indicate which one consumes less.

The main advantage of self-regulation is its speed. Anyone can complain to the courts about the publicity campaign that allegedly violates the law, but by the time the courts have decided this campaign is over, and it is not certain that the verdict will be favorable to the complainant. Advertisers know how to use the umbrella of freedom of expression, something that a member of the Spanish Ministry of the Environment has confessed to us. We have also learned from the same source that some countries in northern Europe have placed some restrictions on freedom of expression and have directly banned the claim that a car is ecological, with or without data. Doesn't sound like much nonsense.

“Self-regulation and not obeying the law?”

Beside the advantages, this self-regulation also has a number of disadvantages. To begin with, it is completely voluntary to sign the code. On the other hand, and as in the case of the self-regulation code agreed by the television channels to preserve the content of their programming, the agreement has been signed by the same ones who previously did not comply with the legislation, that is, the internal regulation that is tougher than what the legislation is.

“Were the signatory companies not obliged to comply with the law?” asked Ecologistas en Acción last year in the press release issued when the code was signed. In particular, environmentalists wanted to remember that all car advertisements, without exception, violated the decree that regulates information on fuel consumption and CO2 emissions. Advertisers are required to provide this information at least as easily visible as the main information of the ad. They didn’t do it before signing the self-regulation code, and they didn’t do it after. Finally, the European Commission opened proceedings against the Spanish State last February, following a complaint by Ecologistas en Acción.

Beyond violating a certain rule, however, Isidro Jiménez would like to go to the heart of the problem: “It’s true that the messages have evolved a bit. Before they put a green leaf in the ad and that’s it, now, at least some companies are making more elaborate arguments, but always without any criticism. It is associated with the idea of ecology that a car reduces its CO2 emissions slightly. But you can’t link energy expenditure to environmental benefit, that’s manipulation. And both manufacturing and using a car requires a lot of energy.” In some Scandinavian country they have already noticed this, but it is so far that we don’t even remember what it is.

Elikagai funtzionalen etiketatuak araudi zorrotza bete behar dute, baina Peralesek dioenez, behin produktua erosita irakurtzen da etiketa. “Ez dago araudi argirik horien publizitateari buruz. Gu, eta beste elkarte batzuk, borrokan ari gara Europa osoan elikagai funtzionalen iragarkietan behar bezala adierazi dadin etiketetan agertzen den informazioa. Jendeak ez badaki oso ondo zer nolako produktua den, badaezpada erosi egiten du eta gero gerokoak. Are gehiago pertsonaia ospetsu bat agertu bada iragarkian”. Hor dute beste borroka fronte bat kontsumitzaile elkarteek: honelako elikagaien publizitatean pertsonaia ezagunak agertzea eragotzi nahi dute.

Elkarretaratzea egin zuen Aiaraldeko Mendiak Bizirik plataformak atzo Laudioko Lamuza plazan, Mugagabe Trail Lasterketaren testuinguruan.

EH Bilduk sustatuta, Hondarribiako udalak euskara sustatzeko diru-laguntzetan aldaketak egin eta laguntza-lerro berri bat sortu du. Horri esker, erabat doakoak izango dira euskalduntze ikastaroak, besteak beste.

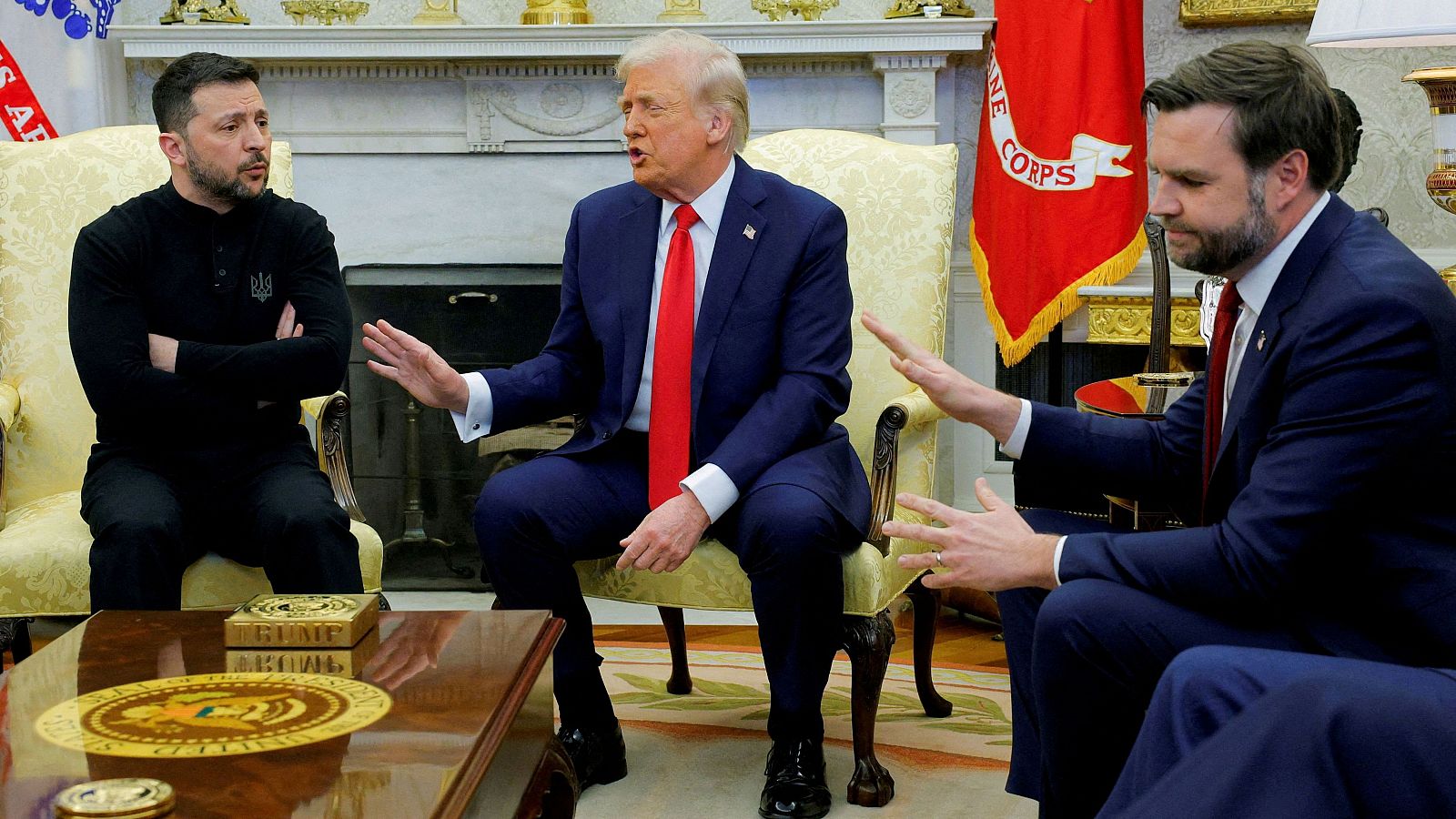

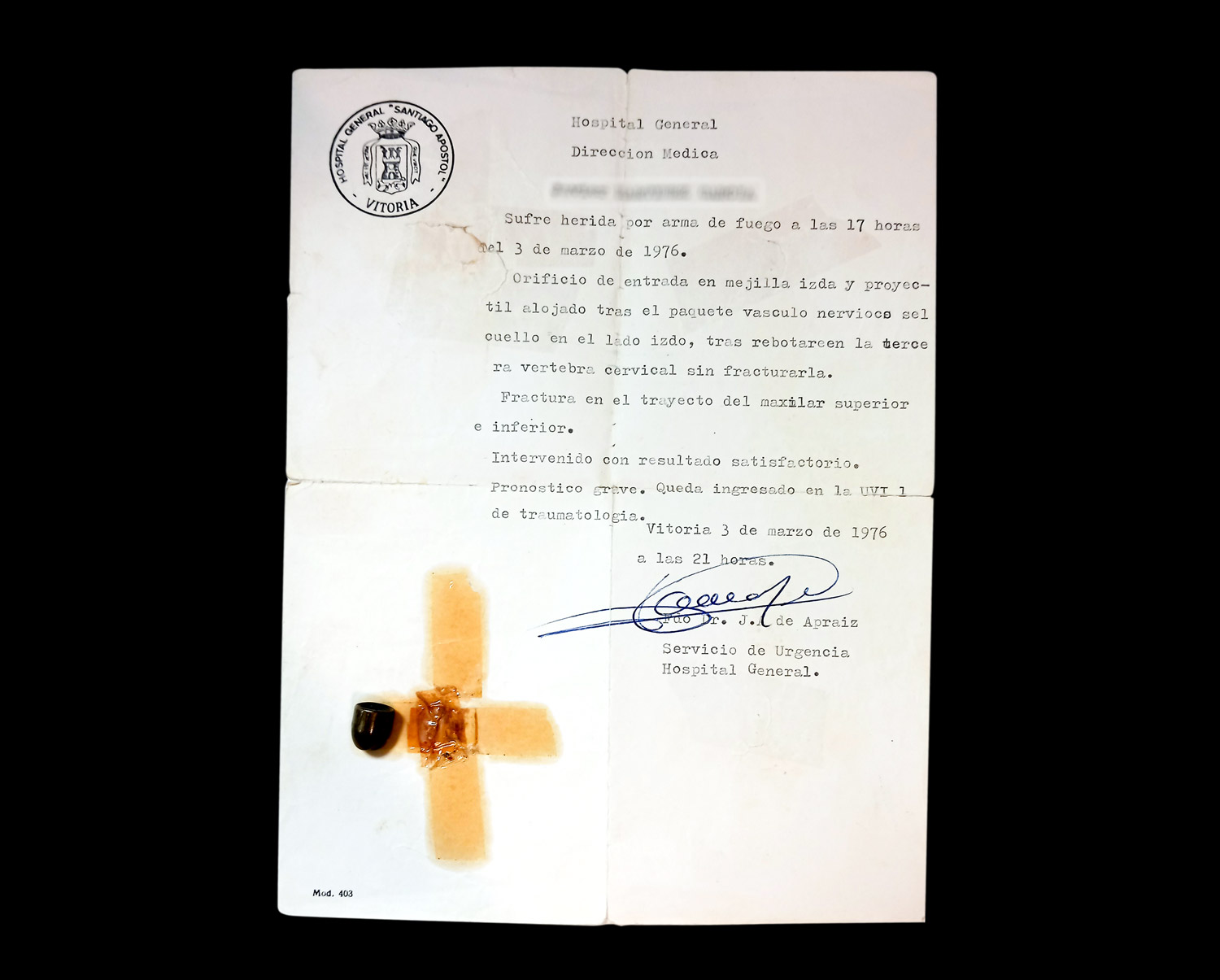

Martxoak 3ko sarraskiaren 49. urteurrena beteko da astelehenean. Grebetan eta asanblada irekietan oinarritutako hilabetetako borroka gero eta eraginkorragoa zenez, odoletan itotzea erabaki zuten garaiko botereek, Trantsizioaren hastapenetan. Martxoak 3 elkartea orduan... [+]

1976ko martxoaren 3an, Gasteizen, Poliziak ehunka tiro egin zituen asanbladan bildutako jendetzaren aurka, zabalduz eta erradikalizatuz zihoan greba mugimendua odoletan ito nahian. Bost langile hil zituzten, baina “egun hartan hildakoak gehiago ez izatea ia miraria... [+]

Udaberri aurreratua ate joka dabilkigu batean eta bestean, tximeletak eta loreak indarrean dabiltza. Ez dakit onerako edo txarrerako, gure etxean otsailean tximeleta artaldean ikustea baino otsoa ikustea hobea zela esaten baitzen.

Leihatila honetan behin baino gehiagotan azaldu ditugu Ama Naturaren engainuak bere izakiak babestearren. Batzuetan, erle edo liztor itxura zuten euliak ekarri ditugu, beste batzuetan inongo arriskurik ez duten arrisku-kolorazioko intsektuak ere bai (kolorazio aposematikoa... [+]

Nori ez zaio gustatzen ahuakatea? Ia denok atsegin dugu fruitu berri hori, di-da amaren batean etxekotu zitzaigun. Zenbat urte da ba dendaero ikusten hasi garela? Gure mahaietara iritsi aurretik, historia luzea du.

Gipuzkoako hamaika txokotatik gerturatutako hamarka lagun elkartu ziren otsailaren 23an Amillubiko lehen auzo(p)lanera. Biolur elkarteak bultzatutako proiektu kolektiboa da Amillubi, agroekologian sakontzeko eta Gipuzkoako etorkizuneko elikadura erronkei heltzeko asmoz Zestoako... [+]

Memoria eta Bizikidetzako, Kanpo Ekintzako eta Euskarako Departamentuko Memoriaren Nafarroako Institutuak "Maistrak eta maisu errepresaliatuak Nafarroan (1936-1976)" hezkuntza-webgunea aurkeztu du.

Espainiako Estatuko zentral nuklearrak itxi ez daitezen aktoreen presioak gora jarraitzen du. Otsailaren 12an Espainiako Kongresuak itxi beharreko zentral nuklearrak ez ixteko eskatu zion Espainiako Gobernuari, eta orain berdin egin dute Endesak eta Iberdrolak.

Gukak “Bilbo erdalduntzen duen makina” ikusaraziko du kanpainaren bidez. 24 orduz martxan dagoen makina salatuko dute, eta berori “elikatu eta olioztatzen dutenek” ardurak hartzea eskatuko dute. Euskararen aldeko mekanismoak aktibatzea aldarrikatuko dute.