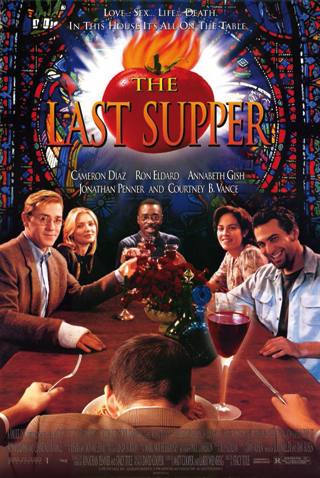

A film that foresaw the era of intereconomics

- Basques of the South: Don’t the extreme right-wing networks that have proliferated with Digital Terrestrial Television awaken your darkest instincts? Don’t worry, you are not the only ones. Not even the first ones. We watched a movie in 1995. The protagonists, fed up with ultra-conservative TV speakers, decided to do something.

Five people gather every Friday in a house, all of them studying at the university, progressive, young. They talk about politics, society, the economy and they are all equally rejected by the presenter Norman Rejthnot (whose role is played by Ron Perlman), who they see on television. His only words explain why: “I am the first to admit that we took this country from the Indians. Either way, what were they doing? Throw arrows with the arches and use the shells as coins.” The reason is at the level of the Intereconomía or Veo Televisión Tertulias. But, these Yankees have always been said before, fifteen years before. The effect, however, is not very different. The outing that now inflames you in the quiet of your living room will irritate the protagonists of the film in the cozy kitchen. Film directed by Luke (Courtney B. Vance) above all. He will begin by saying that the conservatives are not standing still, while they themselves are only leftists, liberals, progres, but talking.

The occasion for action will take place shortly thereafter. Pete (Ron Eldard) suffers a car accident and is accompanied by a man to drive the vehicle home. You'll be invited to dinner. That's Zack. A veteran of the Gulf War, racist, anti-Jewish, defender of Nazism. “Adolf Hitler did invent it” and “The Holocaust cannot be proved.” With this material, you can't have a quiet dinner. The discussion will take a turn and Zack will put a knife in the throat of one of his friends. The tension. The tension. The nervousness. Marc (Jonathan Penner) inserts a knife in the back of the guest, who remains in a hurry. Then the game begins: five people bury the body in the garden of the house and plant tomatoes on top of it.

Then, more people will start to invite you to the table. They will be allowed to speak and, when they have proven themselves to be right-handed to the point of touching the wall, they will be poisoned. The simple reason for doing this is that Luke formulates: “Is it wrong to kill someone if that death makes the world a better place?”

Political violence, mass media and cynicism

The orchard of the house will blush with tomatoes: homophobic priest, anti-environmentalist, anti-abortist, censorship book, all plant fertilizer. They finally get to invite TV star Norman Hustthnot to dinner. And this is where the contradictions will arise: the man who was anathema of the members of the house because of what he said on the screen, is more progressive than you think with the dinner in front of his nose. His reactionary rhetoric is nothing more than a job done for a good salary. For giving reasons that he does not believe, he is cynical; but not a believing conservative. However, following the custom of the time, Luke will want to die and a debate will arise among five friends. Taking advantage of this, and aware of what they intend to do with him, Agabthnot will pour poison into the glasses of the diners.

The film, in its lightness, can offer two or three interesting ideas to the tele-viewer who is fed up with seeing the myths of neo-conservatives dancing. To begin with, you will feel identified with the protagonists: the television model that we now suffer with DTT was deployed with the cable system in the United States a long time ago. In the background, the film also provides an opportunity to read that small-scale political violence has no role to play in front of the mass media. The contradictions between the five friends abound as much as the bodies of the garden, and in addition, the enemy, Norman Rejthnot, who hammers to the left every day, fights for the audiences, not for some ideas. At this point, the protagonists of the film will lose their way. The enemy cannot be symbolized by a single person and the “real” problem will be exposed: that the media market – that invisible, objectified, systemic opponent – is far worse than anyone who actually has reactionary ideas.

It's not a bad lesson at a time when we get tons of garbage to the living room. Anger with the inter-economy is useless. It’s even more useless to want to twist the neck of some presenter of that chain. What to do, Lenin? The film has no answer for that. It is limited to counting the victory of the system. But at least it serves to discover that the enemy can be a pleasant and progressive person. As dangerous as the ultra-right chains may be some supposedly more pluralistic media, even if they are public.

You may not know who Donald Berwick is, or why I mention him in the title of the article. The same is true, it is evident, for most of those who are participating in the current Health Pact. They don’t know what Berwick’s Triple Objective is, much less the Quadruple... [+]

The article La motosierra puede ser tentadora, written in recent days by the lawyer Larraitz Ugarte, has played an important role in a wide sector. It puts on the table some common situations within the public administration, including inefficiency, lack of responsibility and... [+]

Is it important to use a language correctly? To what extent is it so necessary to master grammar or to have a broad vocabulary? I’ve always heard the importance of language, but after thinking about it, I came to a conclusion. Thinking often involves this; reaching some... [+]

The other day I went to a place I hadn’t visited in a long time and I liked it so much. While I was there, I felt at ease and thought: this is my favorite place. Amulet, amulet, amulet; the word turns and turns on the way home. Curiosity led me to look for it in Elhuyar and it... [+]

Adolescents and young people, throughout their academic career, will receive guidance on everything and the profession for studies that will help them more than once. They should be offered guidance, as they are often full of doubts whenever they need to make important... [+]

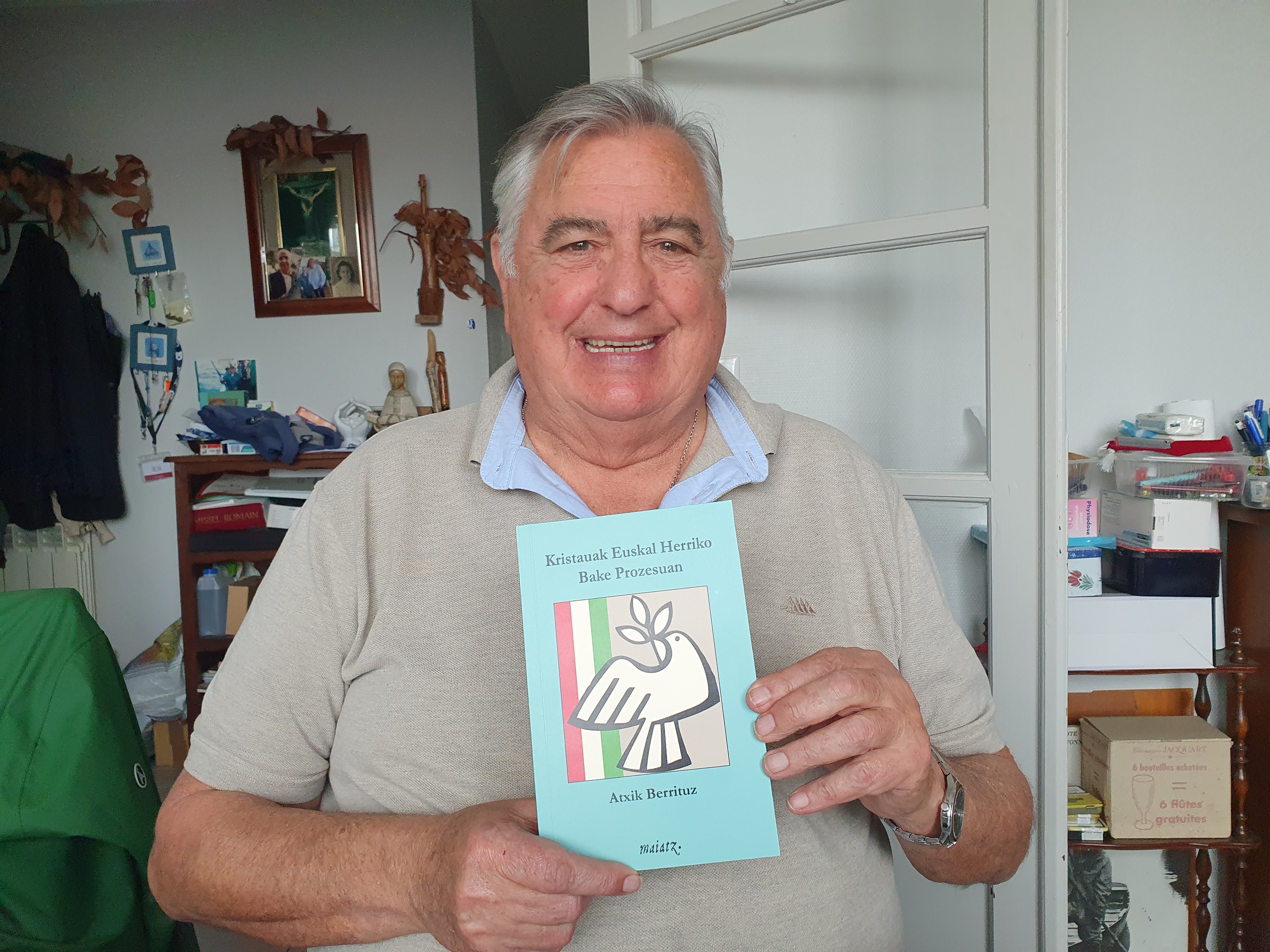

Atxik Berrituz giristino taldeak Kristauak Euskal Herriko bake prozesuan liburua argitaratu du Maiatz argitaletxearekin. Giristinoek euskal bake prozesuan zer nolako engaiamendua ukan duten irakur daiteke, lekukotasunen bidez.

Maiatzaren 17an Erriberako lehenengo Euskararen Eguna eginen da Arguedasen, sortu berri den eta eskualdeko hamaika elkarte eta eragile biltzen dituen Erriberan Euskaraz sareak antolatuta