If our home is in Iberia

- The fact that several Basque singers sang in Basque on the album Kepa Junkera’s Etxea would have caused some slight satisfaction to the Basque. The author of this article can’t say the same; he’s worried not about the records, but about the dynamics he’s seen around him. And in the following lines he will try to explain this concern.

From this classification I would like to question the contribution that this Etxea has made –small in my opinion– as well as the response of the media that has received it in return –bloated, because any other album in Basque does not have as much promotion in us–. You will

listen to popular Basque songs in Etxea with adaptations of Junkera. Each of the singers has given it its own touch: some are close to the “traditional” version, the flamenco air is noticeable in others –like in the Little Baby of Estrella Morente–, the Portuguese musicians have brought a fado air and in general the piano and guitar are the conductors of the music, leaving the small sound in the background.

Result: valid; slightly irregular. The songs with the piano have mainly reminded me of the arrangements that have been made previously in the Basque song industry. Very little news. For example, I have serious doubts about the contribution of the version of Oriko Xoria – singer Pau Donés and Eliseo Parra – of this album, comparing it with the one sung by Pantxoa and Peio. I’ve also had a feeling of Ber with several other songs on the album: despite some minor changes, no new lights at home.

And the doubt (worry) follows this feeling: if there was also intention; that is, to whom this album is addressed. You have to go to the market to find an answer. In view of the content – popular Basque songs, well known to the Basque audience – and the participating singers – many of which can be classified as mainstream in Spanish music; almost all of them from the Iberian Peninsula; no Basque – I have thought and realized that Etxea’s main target does not live in Basque. The idea behind the album is to make the Basque culture attractive to the Basque Country. A similar attempt was made last year by Amaia Montero and Mikel Ersocket-recorded version of Lau Teejo. It is a trend that has been going on for a while, because it is not only a product that can be consumed by the Basque Country’s Basque Country, but it can also be sold throughout the peninsula, taking advantage of the traction that these well-known musicians make from the center of Spanish culture.

The intention is not bad, if the cultural production in Basque is going to live it will be necessary for the Basque people to gather around them, but I doubt that the works proposed in this way will bear fruit in the long term. I’m not talking about this album, but about the model it can create. The problem has long been formulated by Newton: gravity, the force of attraction exerted by the mass of one body on another smaller body. Mass is the cultural industry of the Spanish language, not the Basque language. The big one attracts the small one, sometimes in force, sometimes in balaclavas. I have taken the form of the second to the discourse that has arisen around this latest work by Junkera.

The world is not ours, but neither is the Iberian

The following is a text written by José Saramago on the back cover of Etxea, which someone in the brochure uses: “There is a popular musician in which all the peoples of the world are represented as a common home. The architect and mason (sic) of all this is Kepa.” The phrase would reflect an ideal, of a meeting of cultures that live in a harmonious respect for each other.

I will dare to suggest that there is at least one lie and one truth comparing it to the content of the album. False: here you will not find “all the peoples of the world”; you will find the Iberian Peninsula at the most, and 28 of the 42 collaborators who have participated (66.6%) have their usual Spanish language. The truth is in this “as if”. That is to say, that in this pan-Iberian “common house” he invites us to act as if we all lived in the same situation. “As if”... but it’s not that, despite Saramago’s insistence, we would all win with pan-Iberism. The gravitational force of the Spanish language does not allow this. The postcolonial expressions of some of the collaborators on the album bear witness. Loquillo writes to the newspaper Deia: “I think the collaborators have a lot of love for Basque, we don’t consider it a secondary language” (Excusatio non petita...). Miguel Bosé, much cleaner in the same newspaper, has said that “Basque is the most cryptic of the languages.” I don't think I need to add anything.

Because fiction is the minimum requirement if we are to build a common home: to imagine that the mass of each culture is equal. The discourse around this album has not succeeded in creating this fiction. I'd say he hasn't even tried. The artists who have presented themselves as high-level in the promotion are those who usually sing in Spanish –Ana Belén, Andrés Calamaro, Jaime Urrutia or the aforementioned Loquillo and Bosé–. These are the masters of the house, once and for all and as an extraordinary ceremony at dinner, even if they are speaking the language of the servant. How does that benefit the guy's language? If it doesn't make him more servile... To universalize his language, to be relevant, he seems to be paying the mortgage to open himself to the world, when he had to have the keys in his hand a long time ago.

One of the most prevalent phenomena of the beginning of the 21st century is the gigantic process of integration that is taking place between cultural systems. We are constantly talking about global cultural phenomena –we have been told about universality with this album–, forgetting that in the roots of them there are always local starting points. There are centers with their markets and star systems; their ability to attract depends on their mass. Moreover, each centre, insofar as it reflects a culture, a worldview, has a monopolistic character. And here lies the most obvious problem that I see with this album and the initiatives of the tank: that the center is not here, in the Basque culture. The centre is located in the cultural industries of Erda –mainly in Spanish–, where the stars are the protagonists, they are the ones that give it added value. Otherwise, would a collection of popular Basque songs have had so much marketing? It is an approved excursion to the periphery of the Basque language; approved because Iberian artists have said that now the Basque language is valid for the world.

It worries me to the extent that it makes us an appendage of the Spanish intestine. Of course, it's not the only example. For this case, the media workers attach alimal importance to the Basque novel that has won the Spanish national prize, the Basque actor that has appeared in the Spanish film of the moment. That’s where they have to value what’s here; we don’t seem to know. We don't even know where we have the center, we can be the center.

But as far as the Basques are in the world, the Basque language is global per se; we must not go outside holding anyone’s hand. Even for the outsiders we will only be attractive by building a house with a strong foundation, knowing that we are one of the centers, exporting ours instead of importing the stars.

Friends, we need dynamics that give us a greater force of gravity, if this building that we supposedly have of the world is not going to stay in the corner of Iberia. The house, unfortunately, I think will stay there.

You may not know who Donald Berwick is, or why I mention him in the title of the article. The same is true, it is evident, for most of those who are participating in the current Health Pact. They don’t know what Berwick’s Triple Objective is, much less the Quadruple... [+]

The article La motosierra puede ser tentadora, written in recent days by the lawyer Larraitz Ugarte, has played an important role in a wide sector. It puts on the table some common situations within the public administration, including inefficiency, lack of responsibility and... [+]

Is it important to use a language correctly? To what extent is it so necessary to master grammar or to have a broad vocabulary? I’ve always heard the importance of language, but after thinking about it, I came to a conclusion. Thinking often involves this; reaching some... [+]

The other day I went to a place I hadn’t visited in a long time and I liked it so much. While I was there, I felt at ease and thought: this is my favorite place. Amulet, amulet, amulet; the word turns and turns on the way home. Curiosity led me to look for it in Elhuyar and it... [+]

Adolescents and young people, throughout their academic career, will receive guidance on everything and the profession for studies that will help them more than once. They should be offered guidance, as they are often full of doubts whenever they need to make important... [+]

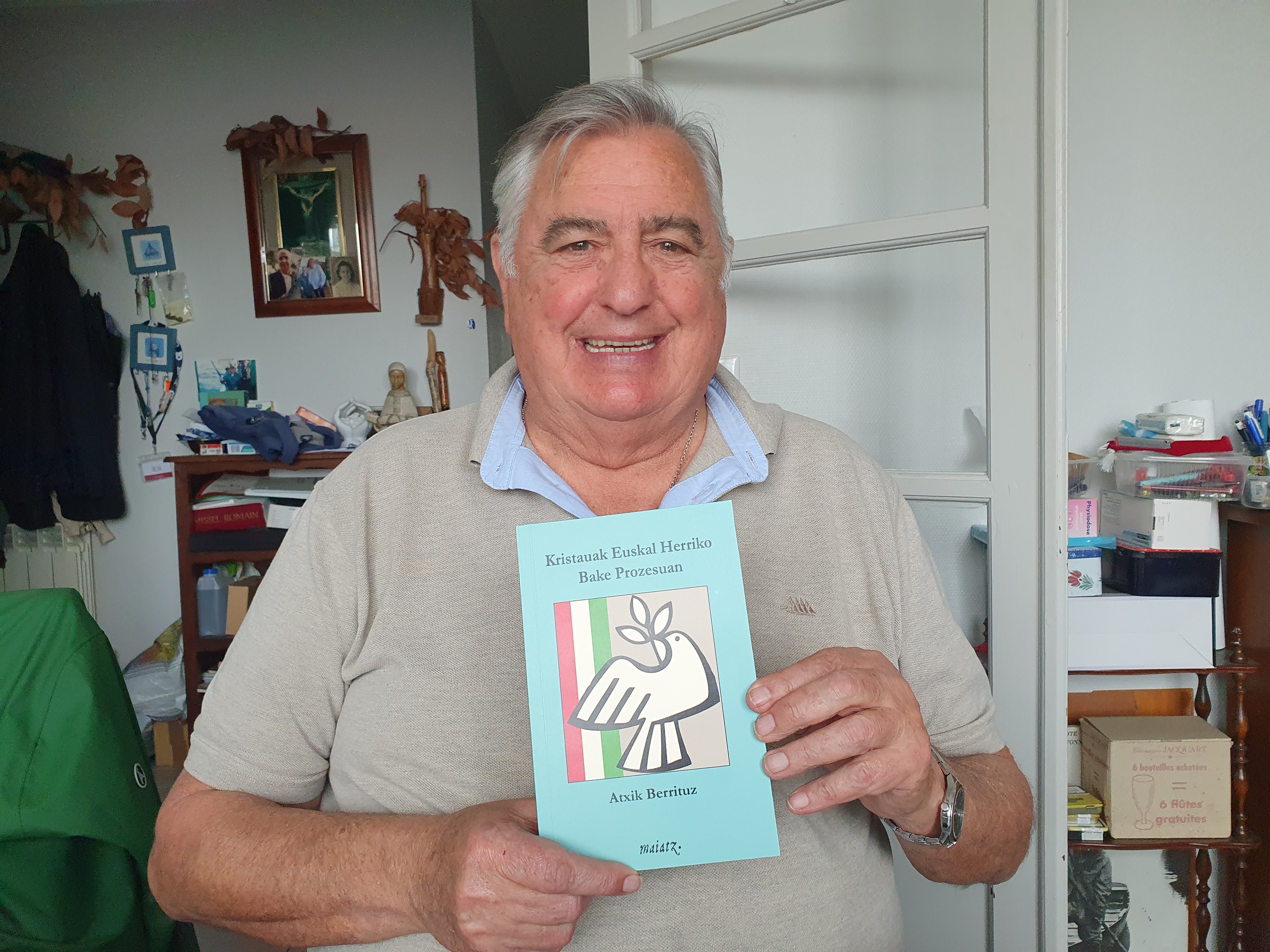

Atxik Berrituz giristino taldeak Kristauak Euskal Herriko bake prozesuan liburua argitaratu du Maiatz argitaletxearekin. Giristinoek euskal bake prozesuan zer nolako engaiamendua ukan duten irakur daiteke, lekukotasunen bidez.

Maiatzaren 17an Erriberako lehenengo Euskararen Eguna eginen da Arguedasen, sortu berri den eta eskualdeko hamaika elkarte eta eragile biltzen dituen Erriberan Euskaraz sareak antolatuta