The Fallen Revolutionary

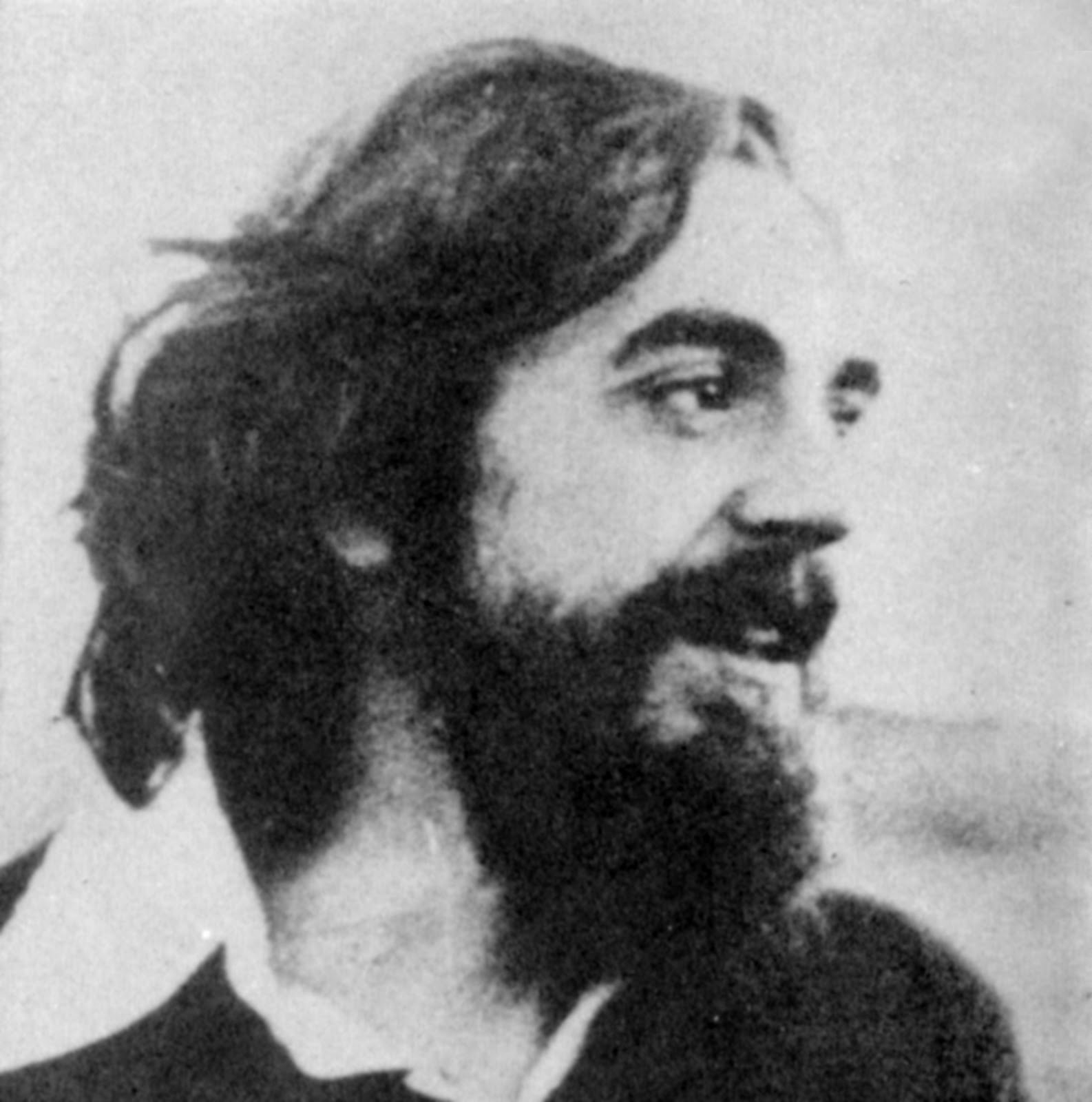

- On July 8, 1978, a young man, Germán Rodríguez, was shot dead by police near the Plaza de Toros in Pamplona. Thirty years have passed since those tragic San Fermín and the historian Josu Chueca is investigating his life. Germán was not by chance on the front lines of the barricades, he had a militant life, and once again he was brought there by revolutionary ideas.

He was very young when Germán Rodríguez was murdered. He was 23 years old when he was shot dead by police on Roncesvalles Avenue. Like him, thousands of young people and adults faced the attack on the bullring by FOP agents, as they had often done in the streets of Pamplona before. In fact, since the first general strike in June 1973, the Navarrese people had a lot of experience in this type of struggle. So it was not the first time that you had been killed – as witnessed by José Luis Cano – but this immense repression at the heart of the San Fermín festivities was not known until then. It was no coincidence, however, that Germán was a direct victim of this mass influx of police officers. Sister Concha said plainly in her last farewell to him: “Since a long time ago, when he gained political consciousness, he was fighting head-on.”

Young people “here and there” in search of revolution

The German generation was a teenager when the demonstrations against the Burgos trial took place. Too young to participate, but old enough to embark on the path of politics. In fact, in the following years, they had two supports to get closer to politics: the mountain groups for young people –Juvenedi, C.D. Navarra, Aquí y Han...– and the committees that were being created among the students, called CEN –Comités de Estudiantes de Navarra–. For German, the Hona and Han mountain group, set up by several young people in Pamplona, was the first school for politicization. This included the creation of the first training groups, debates and political alignments.

They had the highest rainfall because they were Basque. However, the first group of workers of this institution in Pamplona since 1969 was quickly joined by a group of young students, who were mostly grouped in Aquí and Han. It was a time of constant debate; the desire to make the working class the axis of the revolution and the fact that many considered themselves Marxists opened up a vast ideological field within ETA, as observed in the 6th Assembly.

As is well known, with the acceptance of Marxism, those who joined ETA discussed the current and strategy to which they adhered at the juncture following the Burgos process. These discussions began in the spring of 1972, revealing discrepancies between the so-called Mayo and Mino. Thus, while most of the leaders outside the Spanish State approached Trotskyism, the ETA of the interior suffered the consequences of another division.

In this Kinka, Germán and other young people formed a group in favor of ETA(VI), that is, the Mayos. Together with German, Koldo Lasa, Ramon Contreras, Jotajota Goñi and others formed the extremist group that this institution had among its students in Navarre. They would be the promoters, through CEN, of the revolutionary Marxist current in the student movement that was being reconstituted.

On the other hand, Germán acquired a growing responsibility within this institution to help other liberated people who were in hiding, such as José Millán Fitero and José Vicente Idoiaga Jesus or Petto. Although he was young, at a theoretical level he made several important contributions using the pseudonym Garin in order to initiate the ideological renewal of the organization.

Since 1973, the attention paid more and more to the daily struggles of the sexes, who were beginning to perceive a stronger proclamative movement in the workplaces of the Pamplona. For example, the hard strike of Torfinasa in January of that year –which ended with the kidnapping of the main Felipe Huarte– and the solidarity with the comrades of Motor Iberica in June. The latter took all the workers of Navarre to the streets and the general strike of the estreina shook the whole of Pamplona, as well as the industrial zones of all the regions. Something similar to the general strike that Germán and his comrades theorized to end the dictatorship was underway. The mobilizations in solidarity with the friends of Noain’s Motor Iberica showed for the first time the strength of the Navarrese working class and the police were unable to stop the strike that spread through mass demonstrations and pickets.

The first arrest: Rather than denouncing anyone...

The ETA(VI) tried to bring their theories – the use of pickets, the practice outside the Franco’s vertical union, the dissemination of the idea of a revolutionary general strike... – both to the workplaces and to the street, both through their members in the factories and through the leaflets that were dismissed day by day. As a result, the revolutionary clamor was strongly influenced in various places, such as Imenasa. But at the same time, the repression directly affected many of the significant participants of this organization: on the one hand, Iñaki Beorlegi was arrested – he went to Hernani to report the general strike and was arrested there – and, on the other, Germán himself fell into the hands of the police during the night of June 20.

The fall of German was brought about by the use of the workplace in Pamplona by the painter Juan José Akerreta. The place was used by the ETA sexes and supposedly by the FRAP, and after the last ones “sang” this place the police found a suitcase in it with the propaganda of ETA, so they began to follow the trail of this organization. Beorlegi and Germán were then taken to the police station by a different route. As the heads of the two ETA(VI) cells were intercepted, Sainz and the police had a beautiful bargain to completely dismantle the organization. But one and the other remained silent during the period. Iñaki Beorlegi’s colleagues openly said that they would not return to work until he was released, so to avoid a prolonged strike, they had no choice but to impose a fine and leave him on the street. As for German, he was subjected to a long interrogation at the police station; he said nothing. The police were well aware of the organizations whose propaganda had been captured on San Antón Street and to which all the questions had been directed, but without success. In the end, Germán was forced to confuse himself with FRAP activists in order to imprison him, accusing him of participating in the so-called “illegal association”.

He spent a year and five months in prison. In December 1974, after passing through the courthouse, he was released. He spent most of his months in the prison of Pamplona with the FRAP and many other militants who were constantly coming in: The ETA, the GAC... He was also in Carabanchel prison for a couple of months, where he had the opportunity to be with many comrades of his organization. In fact, in the third gallery of the prison in Madrid there were then a large number of members of the LCR-ETA(VI) and they had formed something similar to the “Red University” to deal with the texts of the IV International, among others.

After his dismissal, because he was “burned” in Navarre, he spent a year in the area of Bizkaia. It was there that he dedicated himself to internal work, the organization had a very large number of revelers –Standing, Imprekor, Combat, Proletarian...– firing. He worked in this activity until the death of Franco, whose new situation after the disappearance of the dictator allowed him to return to Pamplona. By then, the thirst for freedom was insatiable. In addition to the struggles for amnesty, the clamor for democratic and national rights was increasingly echoed, while

representatives of the regime kept the traditional repressive stick. Parties that were still on the margins of legalization grew and formed dense networks of militancy among all groups.

On the other hand, there was the tenor of forming youth organizations. In fact, most parties were beginning to work on different policy areas and saw the need to address the problems of women or young people. The German political movement, i.e. the IV International, had some experience in this, as they had previously formed youth groups in various places. This was something new in Spain. Germán founded “Revolutionary Groups” in the Basque Country with other young people coming from the student movement and began to structure groups called JCR (Revolutionary Communist Youth) in the State. To carry out this youth policy, the conference held in Montpellier in the summer of 1976 was key. The Pamplona had to go there, passing the border in secret. Local meetings were organized to publicize the decisions of this Congress in other nations. The Basques had their own in Arantzazu, the first anniversary of Franco’s death. Germán was a youth delegate and was arrested like everyone else as soon as the conference began. The Pamplona police were then able to confirm what they had known since June 1973. But the political context was already very different. Although they had not overcome the legalization threshold, this type of group was gaining legality, and after spending a few days in the police station they were all left on the street.

From Internationalism to the Little Revolution in the Neighbourhood

During the transition, the mobilizations for amnesty in the Basque Country repeatedly took people to the streets. Demonstrations and strikes continued to splatter workplaces, schools and squares. The demand for a general amnesty was the main motto and stimulus of the time. In addition, the elections of June 1977, which were the basis for the legalization and reform of the parties, were getting closer and closer.

In this new context, Germán remained in militancy, but outside the political leadership. He resumed his studies at the School of Agricultural Experts and with some friends –Joakin Huarte, Patxi Erdozain, Patxi Lauzurika...– he had the opportunity to denounce and try to solve the deficiencies that this school had. However, the student movement was still modest and, like many, resorted to other social movements. He entered the Society of the Old Town of Pamplona. A shelter with a small loft in Calle Kaldereria, located in the heart of this neighborhood. Thus, Jaime Morras, with Lidia Biurrutia and new friends, began to face the deficiencies and threats that the interior had.

Although the first municipal elections were still pending and the city council of Pamplona was in an increasingly critical situation, several parking projects were exposed. One of them was planned around the Plaza de Toros in Pamplona; the City Council wanted to remove the garden and dispose of its beautiful banana plantations to set up a large parking space. For this reason, in the spring of 1978, the neighborhood associations strongly opposed this project. On the other hand, they promoted an exemplary research team to analyze the problems that the Old Town had –the obsolete housing situation, the scarcity of green areas, the process of commercial eviction...– and of course, Germán was the salt and pepper of all this. They would be his last fights, those attractive feasts of proclamation and denunciation that can be seen in the photographs of the time.

San Fermin 1978, killed at the party

Soon afterwards, around this bullring, the alleged defenders of public order committed an attack that could never have occurred to anyone. As is well known, the banner calling for “full amnesty” was the pretext for this action. It was not new that such demands could be echoed in the bullring; in other years, through the songs and banners issued by the peñas, there were many clamors and protests. In the year in which Germán was imprisoned, for example, in San Fermín in 1973, friends of the Peñas demanded the release of the detainees after the end of the bullfight in the stands. The police then threatened the protesters with megaphony, but the issue did not go any further. In 1978, however, the appetite for repression was much greater. The first of May that year ended with riots and arrests in Pamplona. A few days later, members of the extreme right and several civil guards marched in the Old Town of Pamplona, attacking the headquarters of the LKI and arresting 47 people who entered the area in search of protection.

The head of the National Police, Commander Fernando Avila, had been proudly present since his arrival in Pamplona. He and Commissioner Rubio ordered the Greyhound Rush in San Fermin under the pretext of the banner. From the beginning, firearms were used in the bullring, causing the first gunshot wounds in the stands. In addition, the confrontations in the surrounding streets in the following hours made things worse. Germán was a direct witness to these attacks, since that afternoon he was in the bullring with his lifelong friends –Laura Biurruti, Jotajota Goñi, Koldo Lasa...– and several members of the French LCR, among them the Alain Remoiville of Bordeaux. When the cops were released, the group dispersed, some to help the French friends get out of the square, others to confront the attackers. In the end they all came out, but of course this unequal struggle in the street continued.

The unexpected, which had already spread throughout Pamplona, bore the burden of death. The excessive force and fury used by the police hit hard – even the next day, through the radios, the officers said, “Don’t worry if you kill him.” That's how Germán was killed. Near the Plaza de Toros, where Avenida Carlos III and Roncesvalles converge, Germán joined his classmate and comrade, Patxi Lauzurika. Soon after, the police seemed to be going backwards, Germán, Patxi and the rest were happy to think so, but several police officers came down from a jeep and shot people again with cetm. That's where Germán fell, hit by a bullet in the head. Accompanied by Patxi Lauzurika, he was quickly taken to the hospital in Navarra; he no longer regained consciousness and that night gave his last breath. What Sister Concha said at the cemetery was absolutely true. Clinging to the motto of his political current, his behavior was as exemplary as it was sincere, a constant revolution, a constant struggle.

Horrela, ekainaren 29ra arte Burlatako kultur etxean zabalik egongo da gertaera haiei buruzko erakusketa berezia. Erakusketa horretan hainbat artistek egindako lanak ikusteko aukera dago. Bestalde, herri batzuetan hitzaldiak antolatu dituzte; ekainaren 20an, esaterako, Etxebakoitzen eta Huarten aurreikusi dute hitzaldi bana.

Ekitaldi nagusia ekainaren 27an izango da, ostiralarekin. Bertan, Fermin Balentziak eta Mikel Elizagak konposaturiko kanta ezagutaraziko dute eta 78ko San Ferminei buruzko bideoa ikusi ahal izango da Iruñeko hainbat lekutan. Gainera, zenbait idazlek bereziki egindako testuak ere irakurriko dituzte.

Uztailaren 8an, ohiko omenaldia

Urtero bezala, uztailaren 8an omenaldia egingo diote Germani bera hil zuten tokian; Iruñeko peñek, 78 San Ferminak Gogoan batzordeak eta Aministiaren Aldeko Batzordeek antolatu dute ekitaldia. Zezenketa bukatutakoan manifestazioan joango dira Carlos III.a etorbideraino; aurten gainera, haren omenezko hilarria hor izango da. UPNren Udal Gobernuak kendu egin zuen obra batzuk aitzaki hartuta, baina iazko azaroan berriz jartzera derrigortu zuten herritarren protestek eta Udal plenoak.

I don’t know exactly when this article will see light, but I imagine that by the time it comes out, the act of July 8, 2018 will take place in memory of the 40th anniversary of the death of Germán Rodríguez.

I have no doubt that the Town Hall Square will be filled to the... [+]