"Surveillance has to have a negative connotation and generate a political conflict"

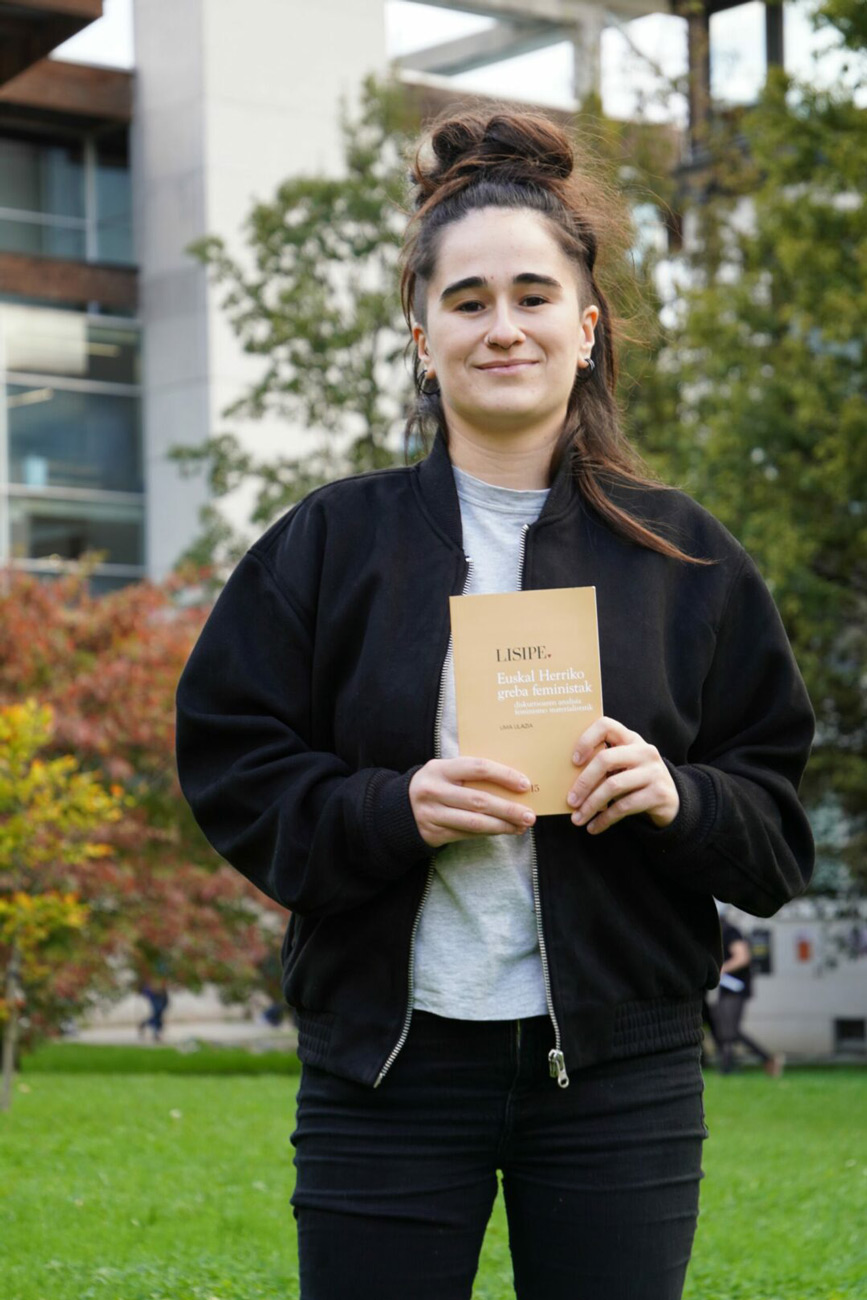

- “Heterosexuality is collaboration with the antagonistic class, that is, with the class of men.” Uma Ulacia, a feminist strike from Euskal Herria, has just published the discourse analysis from materialistic feminism (Lisipe, 2024). He has analyzed in depth the two feminist strikes that took place in Euskal Herria, the 2019 and the 2023.

It is easy to meet Uma Ulacia (Mutriku, 2001) in the assemblies and activities organized by the Feminist Movement of the Basque Country. In recent years it has reconciled meetings and militancy with reading and writing. As a result, he has just published the feminist strike of Euskal Herria, an analysis of the discourse from materialist feminism, the fifteenth essay of the Lisipe collection. It analyzes in depth the two feminist strikes in the Basque Country, the one in 2019 and the one in 2023. Ulacia is concerned about vigilance, the polysemy of the word and the romantic connotation, and defends the need to order the discourse of care. It has also been convinced that care should come from the family, from the market and from heterosexualities and that materialistic feminism is the most effective and radical tool for this.

He has published a book on the speeches of feminist strikes in Euskal Herria. For what purpose has this examination been carried out?

I started the book with a political concern, a few weeks before the second strike. I saw that care was at the center of our discourse, but we were using very different forms of care: law, collective responsibility, necessity, desire... We had to sort out all those speeches that we were creating in the feminist movement. It's an interior attempt.

The feminist movement has used strikes as a tool in recent years. It confirms that, beyond the conflict between employers and workers, there is also a conflict between men and women. It is not an essentialist approach, but it argues that women are a social class. Why are we a social class?

The premise of patriarchy is that we are born to women and men, and this naturalness is attributed to some work and knowledge. Ours are generally the most precarious and the least valuable. Under the pretext of nature, what they wanted to block, we turned it into a battlefield from materialism. That is, it is not nature or biology that distinguishes between sex and gender, but power. That is why we are talking about a patriarchal production relationship. From a materialistic framework we defend the conflict between classes.

The 2019 strike was only summoned by the Feminist Movement, and that of 2023, allied with other sectors, such as the majority of trade unions or social movements. This is the most obvious change. What did this change mean in the movement strategy?

I value it in a positive way, from particularity we have made the leap of the general and we have embarked on alliances. But at the same time, we have had to organize with men, and that has its risks. We have created some mechanisms to block the power of men and to apply them to strike committees: the right of veto is an example of this. These mechanisms are necessary for our struggle.

Care is one of the fundamental axes of the discourse of the two strikes. Why should the feminist movement address care?

Because care is a job performed by women in an unpaid or precarious way, because caring is expropriating and because care impoverishes us. What makes us women have to take care of ourselves. That is why we must be at the centre of our agenda.

After analyzing the discourse of the two strikes, he concluded that in 2019 the discourse on care was materialistic and in 2023, instead, idealistic. Where does the difference look?

With regard to the discourse of sex, there was a need for women and men to disappear in 2019. That meant a great confrontation with men, with the class of men. They were not called to strike. However, in 2023 there is no question of the disappearance of the sexes, which is a moderation of the discourse. In other words, the relationship between men and women will remain conflicting, but there will be a more normalized relationship. As for surveillance, in 2019 there was more talk of powerlessness and power and in 2023 of the need for a right.

As for the political impact and feminist mobilization, what benefits did the idealistic and materialistic proposal bring?

These are elections based on political objectives. That is to say, in 2019 we wanted to deepen the cultural war and for that we needed radical tools that would bring us materialism. To achieve a feminist state of Euskal Herria, we had to build a new hegemony. By contrast, by 2023, the goal was another one. We wanted to negotiate and negotiate requires restraint. That is why we opted for idealism and it was useful, for example, to ask for the publication of care. I don't want to fall into the dichotomy of the good and the bad of idealism. We must be materialistic using idealism strategically.

“Materialism posits that we must problematize all our relations with men. There are not bad and good men, but a privileged social class”

You don't want to fall into the dichotomy, but throughout the book you do an apology for materialistic feminism. Why is it attractive and valid?

Materialism suggests that we must problematize all our relations with men. There are not bad and good men, but a privileged social class. This incites the fight against heterosexuality or the fight against the nuclear family, creating conditions for some struggles to be at the center of feminism: bollerism or anti-razism. There is no material and symbolic struggle against it, there are structural violence and we fight against it from materialistic feminism.

When you've studied the discourses on care, you've left us some homework. It says that it is necessary to define what care is. What is custody?

The concept of care is polysemic and we are using many definitions at once. If we want to avoid interested senses, we need to decide what we call care. There are three senses right now. The guard is expropriation, law and collective responsibility. In the first case, it should be abolished, vindicated in the second and redistributed in the third. With the third connotation we have to be careful because it can lead us to the romanticism of care and to deny confrontation. Consequently, we see that men, companies and governments continue to adjust the positive definition of care to their interests and to strengthen capitalist, privatizing and familiar policies. Surveillance must have a negative connotation and generate political conflict.

Care can also feminize and heterosexualize us. If we think about a radical care proposal, how can we take care of gender and heterosexuality while we dispose of it?

From feminism we try to value everything that forces us to make women. Care is an example of this. But we want to give it value without freeing ourselves from imposition, and we get the opposite: reinventing and strengthening femininity and femininity. It's very dangerous and violent.

“We need the demystification of relationships between partners and the nuclear family in order to create radical care, and for this, the leadership of the slavic subjects in the feminist movement is essential”

Not everything is danger. You see the Bolera struggle as a fundamental axis for building a radical care proposal. What does this mean?

Bollerism is the way out of heterosexuality. Materialism does not limit heterosexuality to the desirable relationship between women and men. On the contrary, it is a general form of relationship between women and men. That is, heterosexuality is about being pleasant for men and, as a result, relating with them. That is, to value everything they say, to take responsibility for their needs at all times, to reproduce gender performativity, etc. Heterosexuality is collaborationism with the antagonistic class, that is, with men. We need the demystification of relationships between partners and the nuclear family in order to create radical care, and for this, the leadership of the slavic subjects in the feminist movement is essential.

We're talking about feminist care, but patriarchal institutions and some parties are trying to steal the discourse. How do we deactivate this speech? Do we have to face up to them or negotiate?

We have to demand publication to get out of the private market and the family. In Euskal Herria, at the moment, our governments are betting on familiar policies. We asked for a negotiating table the day after the strike, but they did not listen. Confrontation and denunciation are therefore essential to our strategy.

I want to look to the future. What will the surveillance system of Euskal Herria look like?

All care work shall be excluded from the family and the market and shall be compulsory and rotational. The aim is also to end custody.

Bizitza erdigunean jartzeko abagunea ikusi genuen feministok zein ekologistok Covid-19 pandemia garaian. Ez ginen inozoak, bagenekien boteretsuak eta herritar asko gustura itzuliko zirela betiko normaltasunera. Bereziki, konfinamendu samurra pasa zutenak haien txaletetan edo... [+]

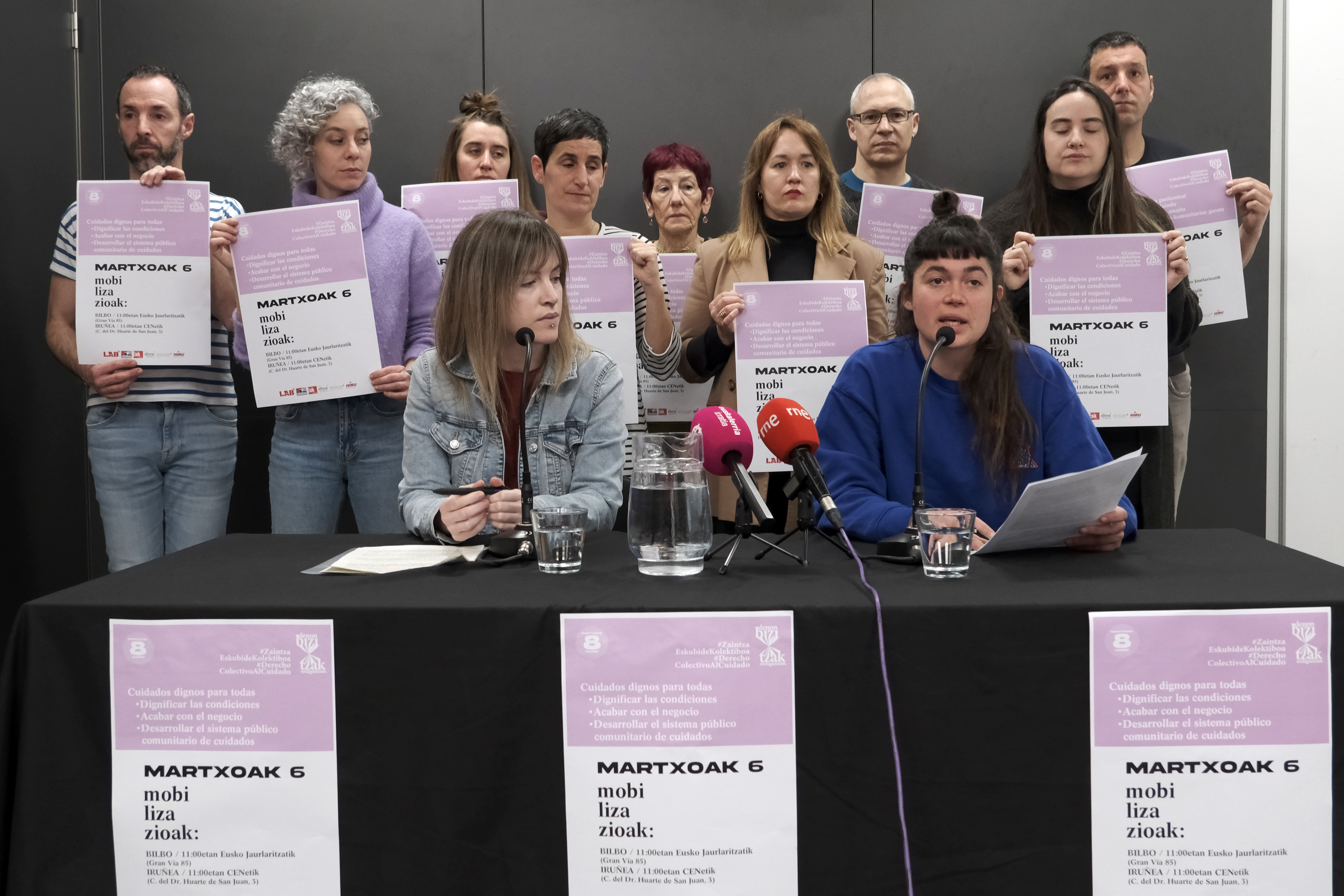

Martxoaren 6an 11:00etan Bilbon eta Iruñean mobilizazioak egingo dituzte sindikatuek, patronalak eta Eusko Jaurlaritza zein Nafarroako Gobernua interpelatzeko, zaintza eskubide kolektiboari dagokionez.

Our towns and cities do not take care of us. We lack land, green areas, community spaces. Our people are designed to serve the capital. In the care village, however, life is the center.

Before, there was a main street, a gigantic street that crossed the city. Consumption and... [+]

Etxeko langile diren eta zaintza lanetan aritzen diren emakumeentzako etxea abian jarri dute Berriozarren. Zortzi pertsonendako lekua duen pisua gaitu dute zaintzan diharduten langileak 6-12 hilabetez espazio duin eta seguru batean bizi daitezen. SOS Arrazakeria Nafarroak eta... [+]

Together with racism, machismo, classism and eleven others, we could also place old age, frivolity. Although the exclusion that can be tolerated on the basis of age is possible for all, when faced with another type of discrimination, the reality can be hardened. Simone de... [+]