How to Create a Criminal (and Why Carpentry Criminals Aren’t Prosecuted)

- The week of the Basque black novel is celebrated in Baztan from the 20th to the 26th. Among various book presentations, colloquia and other events, the morning round table has generated extraordinary expectation. In fact, under the pretext of the black novel, they have also talked about how a criminal is built.

Both speakers have such a close connection with criminality, if it can be called it, and with literature and/or the art of telling: Mikel Elorza, who is not only a columnist in Berria and editor in Susan, but also a “defender of criminals”, since he is a lawyer by profession; and Edurne Elizondo is a journalist who interviewed “criminals” who, among other things, defended the Itoto dam – as he is called, the so-called Official Version – and the case is closely followed, as well as the case of Yolanda Barbazina, the last one who launched Zarotango, especially in the decade of the AHT. The talk was led by journalist Isabel Jaurena.

The subject of speaking and speaking, the broad question with many thread ends, the same question: how is a criminal constructed?

The organizers of (H)ilnegra have given context to the function of the round table, addressed to Elorza: “Mikel, you are not only a fan of black novels, but also a lawyer, and you will know criminals well. Well, we at Baztan are also learning what it is and what it is not to be a criminal. But we want to learn more, and a lawyer can be an ideal companion for that.”

Thus, the first commission is sent to Elorza, not just any one: define what a criminal is. He replied quite intensely, constantly confused and seldom explicitly at any given time, referring to literature or advocacy: “The criminologist Cesare Lombroso characterized and defined criminals as having long ears... What is clear is that the criminal is made. The factors may be of all kinds, but the family and socio-economic situation are the most important.”

He has continued his conversation in a cytolical tone, separating the criminals into two groups: the losing criminals, that is, those who end up punished and imprisoned; and the winning criminals. “The latter have recently gathered in Davos,” he said, citing the fact that the wealthiest in the world have gathered in a congress in the Swiss city of Davos and have made a living of Trump’s economic policies. This is how Elorza finishes it: “There are two options to oppose them: to commit a series of small or large acts of disobedience that are severely punished; or to make literature, from fiction or not, to oppose them.”

The media builds the criminal

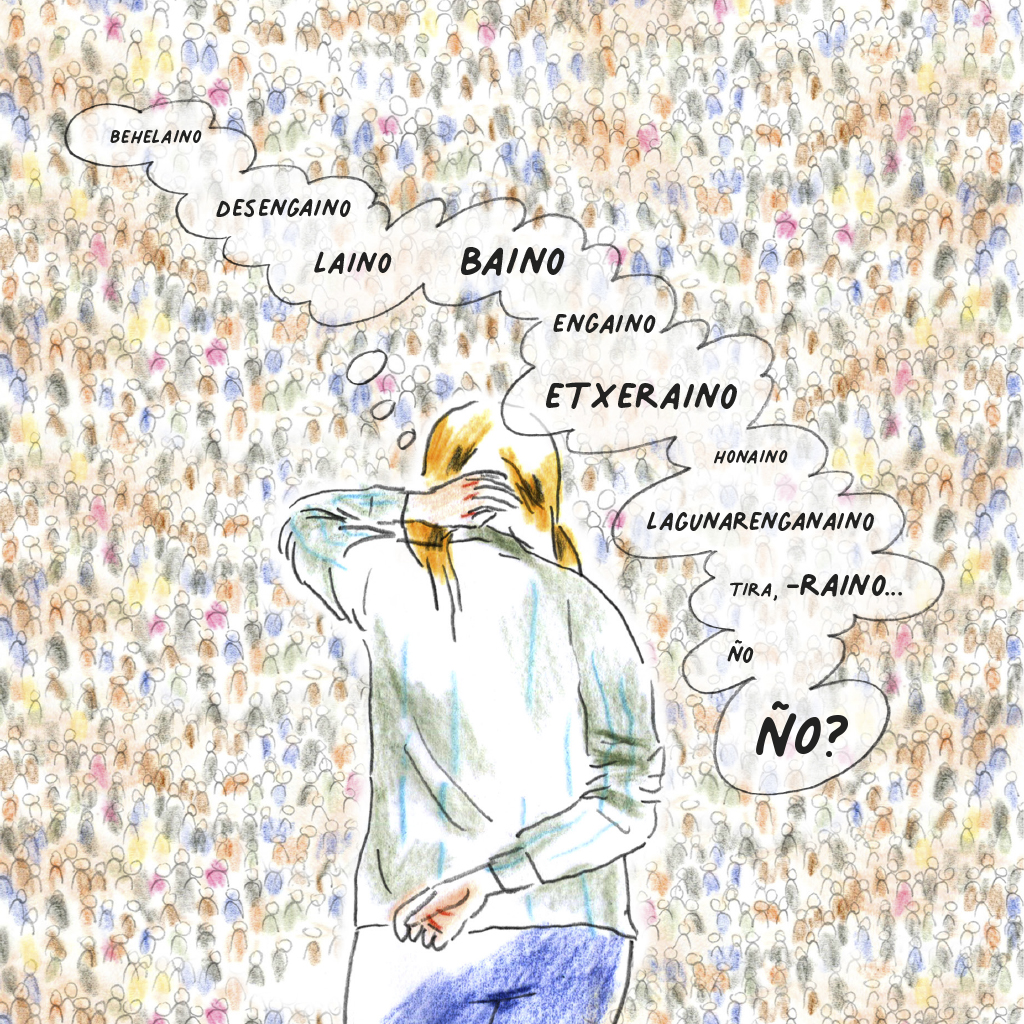

Although there is little literature in the media, there is a large number of devoted people building criminals in some newsrooms. Criminalization is received from society and begins to be criminalized in the police stations, said since Elorza lived as a lawyer, but it is built, built in the media. The journalist Elizondo said: “We live in power relations in this society, which determines how you will be treated by the media.”

Assisted by Edurne Elizondo: "Depends who you are and what crimes you've committed, they easily forget you."

Elizondo refers to the cataloguing of criminal winners/losers that Elorza has previously made, giving an example that caught his attention during his visit to the Parliament of Navarre on a day of open doors. As is customary in institutional places, this is a room in Parliament where there are cadres of former leaders. It was there that he met the ex-president Javier Otano. The PSN member, during his presidency, was intercepted by a bank account in Switzerland and resigned in 1996. The matter was subsequently prescribed by the judges. But in these door-opening sessions they made no mention of the bribery case, as Elizondo recalls: “It depends on who you are and what crimes you have committed, they easily forget you.”

The case of Diego Yllanes is an example of such impunity: Yllanes claimed the right to “be forgotten” immediately after his release from prison in 2020. However, the National Court of Spain did not grant the request.

“On the other hand, if the defendant belongs to an oppressed group, it is easily reported; and if the victim belongs to an oppressed group, it is re-victimized,” says Elizondo. The members of the oppressed collective ultimately become the representatives of the collective. For example, Elizondo recalls a campaign carried out by the former mayor of Pamplona, Enrique Maya, who pointed out young immigrants to blame for “insecurity”.

The media builds the criminal largely because they consider various sources to be 100% reliable. These are the voices of a city council and/or the police, Elizondo says they should be questioned. Among other things, because the case of the Senegalese of Pamplona, Elhdaji Ndiaye, was evident: According to some “he died”, but the testimonies of neighbors and witnesses gave different details.

Elorza places the point on this last statement after the Church: “The official version, like the verse, is built from the end. That is, they decide that you are the criminal and will look for a way to prove that this has been the case.” Things are not new: a narrative is built and some judges buy the speech. Sometimes, according to Elizondo, there is strength to reverse the official version – in the case of the young people of Altsasu, for example – but in many others it is not. Then there is another branch: some media can judge a certain person and group to four columns, but if there is an absolution, then it is possible that nothing is published.

Towards the end of the conference, the microphone batteries have been dissipated, and one who was in the audience has taken a lot out of his pocket. You can't skip the point Elorza: "Be careful to carry a lot in your pocket... It may be normal to have it in the car, like turpentine ('aguarrasa'), but it may also be normal to have a reason to spend a few hours at the police station."

What does this have to do with literature?

In order to influence society in the way that journalism is a tool, for better or for worse, depending on the place and form in which a criminal or presumed criminal is located, literature has a lot of that. What a story, such a criminal. Good literature – words that can be associated with journalism – is, according to Elorza, the one that begins to narrate a crime and tells how society itself is. In this sense, this column of Itxaro Borda was in Nueva and has been referenced by Elorza.

The figure of the criminal has been cultivated quite a bit more in the cinema, at least in comparison with literature. Not to mention those on which the trials are based. “Lawyers hardly appear in literature; we are boring,” says Elorza with a sense of humor. Investigators or detectives, on the other hand, yes; but in their opinion, some sinister and concrete societies have more weight. “The criminal is often irrevocable; he is led by a context to commit the crime.” Or pushed by a woman: “My impression is that women are usually not criminals, but they are very bad, they can be petting, etc., but the one who commits the crime with his hands is the man, the poor man.”

Elorza emphasizes that there are changes in the way crimes are told, globally. “I like the black novel, the matte black; but now we are seeing the bright black, with splashes of blood, which is close to the audiovisual form.” He calls this a Basque noir. In fact, the black novels located in the capitals, written in abundance in the herds, are spreading especially in the Northern Basque Country. “But without a political context”, and that is what Elorza misses. The black novel in South America, for example, says that it is closely linked to the sociopolitical situation, even in Africa, even if it comes less. The formula that Elorza has highlighted is the insertion of a black plot in a certain socio-economic situation. And he says that in the Basque Country it’s not too much: “This has been conditioned by the struggle and armed conflict. ETA is very present in the literature, but what hasn’t been is a black novel with more detailed reflections. There is, but little.”

He's turning that around, though. This is how Elorza stands out. To organize such a round table and receive such a response from the people is not of any kind. It is clear that Elizondo is not just Dolores Redondo.