Navarre as axis, "Olerkizketa", by Patxi Zabaleta, on the Basque imaginary

- Navarre in the Basque Epic. The writer and politician Patxi Zabaleta presented last Tuesday at the headquarters of the Euskaltegi Arturo Campión of Pamplona his last book, Olerkizketa, to recognize “the importance and influence of Arturo Campión as the oldest institution in the world of the Basque Country in Pamplona”.

Zabaleta explained that the book has an anthological tone and that he wanted to analyze what Navarre is in the Basque imaginary, through endless reflections and poems. He wants to make “a contribution to Basque imagery”, looking from Navarre and “criticizing” writers who have recognized Euskal Herria. That is where the second part of the title, Poetry, acquires meaning. In his view, the genre of epic has a bad reputation and that is why more than one good Basque writer has not called his poetry epic, but it is epic, “peoples often seek in epic opportunities and arguments to recognize, affirm, reclaim and extol their identity.”

In this sense, he refers to and analyzes works by authors of diverse perspectives, such as Gabriel Aresti, Orixe, Salbatore Mitxelena or Xabier Lete. Consider Aresti’s poem “I will defend the Father’s House” as an epic and he criticizes him by saying “I will defend the house of the descendants.” The writer says that a people needs a conscience to be a people and that this is worked through imagery. Above all through poetry, but also through prose, it addresses in 69 chapters various themes of Basque imagery such as the people, the hamlet, the city, the Basque country, territoriality, history or ETA.

As he explained in the presentation, “Navarra is a country to which all his imagination gives him a national character and in which there is also hidden struggle”, for example, with Bizkaia: “If you ask a Biscayan about how Bizkaia was formed, he will surely mention the myth of the White Lord, but Bizkaia emerged from the division of the Kingdom of Navarre”, on June 4, 1076, when his brother brought down King Sancho IV.ena through the Peñalén canyon. “There the Kingdom of Navarra really was divided, and therefore in Peñal it is a symbol of our territoriality, nobody mentions it, but Castile then occupied half of the kingdom. If you remember Amaiur and Orreaga, why not Peñal?” The topic is addressed in the poem “The National Shame of Peñalén”.

In his view, he also wished to oppose historicist images, as he says in the preamble to the book: “It seems to me that Basque historiography has often collapsed in historicism.” That is what has happened, he says, because he has wanted to respond to the attacks of the historiography of the two neighboring states, but “history is not a mandate and cannot or cannot force the future; if so, freedom would be erased.”

In his work, Zabaleta explains that, although he focuses on the past and the imaginary, it is above all to look to the future. That the Basque epic has evolved as follows: “XX. He had to move from the “Aradianism” of the 20th century to the “street aesthetic” and that step he took with Basque literature.” Salbatore Mitxelena, Lizardi, Labegerie, Lete, Monzón, Artze are some examples of a route: “We are thrilled with his letters; but let’s confess that, taking the txapela off, the harsh and strident Rock Vasco has covered ointments, scarves, ugly and peracas on the wounds of everyone else.”

Navarre has been one of the axes of the Navarre politician and writer in life and here also ends with Navarre: “On the trip to Euskal Herria Navarra it is not an episode; nor is it the epic of Euskal Herria; or it is a time of Basque epic. On the contrary, Navarre is the one that gives national and state meaning to the Basque Country, so it marks the course of the Basque epic”.

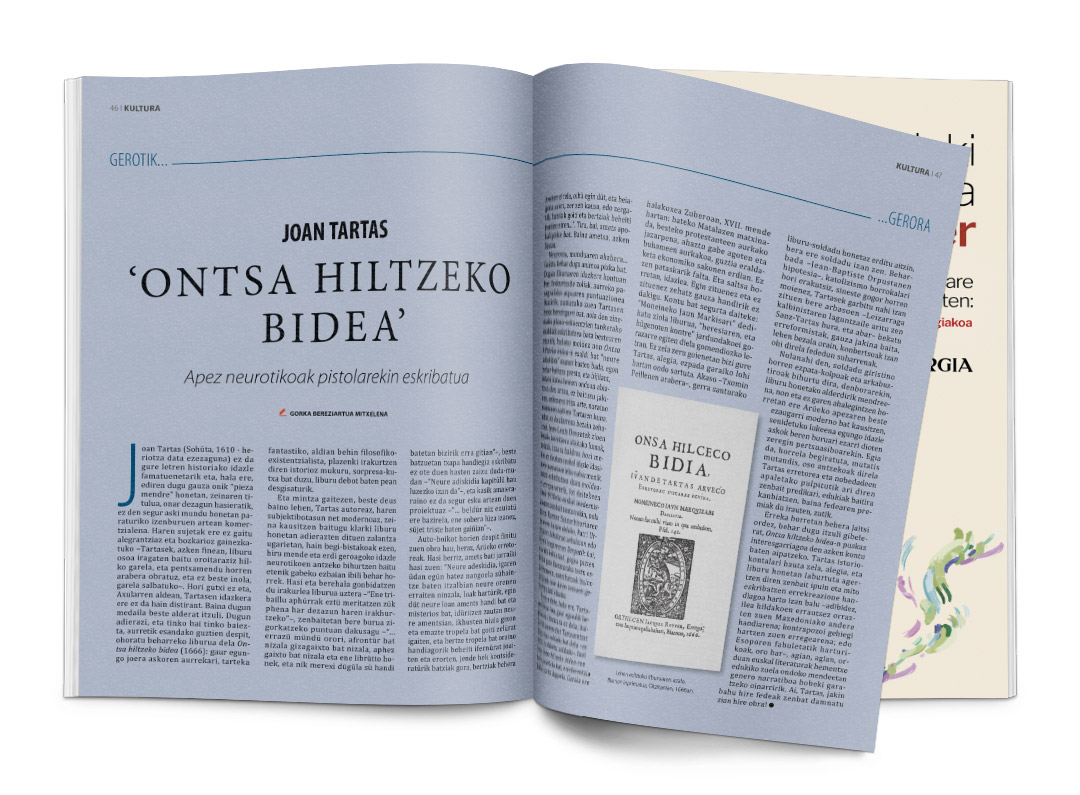

Joan Tartas (Sohüta, 1610 - date of unknown death) is not one of the most famous writers in the history of our letters and yet we discover good things in this “mendre piece” whose title, let us admit it from the beginning, is probably not the most commercial of the titles... [+]

ilbeltza-(1).jpg)

.jpeg)