Mauthausen, slaughterhouse of Basque deportees

- It is 75 years since the liberation of the Austrian concentration camp at Mauthausen in western Austria. During World War II he had a terrible mission: to kill the prisoner until his exhaustion. It was the Nazi camp that brought the most Basque population together and only one in three who went to it managed to survive: Marcelino Bilbao was one of ellos.Este the forgotten chapter of a disgraceful history of Basque deportation.

"We were working in the quarry, when a group of Jews started coming down the stairs. Then one of them signaled and they all rushed to the ravine. The first came from behind, the second, then the third, the fourth -- the Jews died a lot in the quarry! (…) The most surreal thing is that the SS treated these suicides as sabotage.”

The atrocities that took place in the concentration camps of World War II often seem to us anecdotes of a remote history, as if they had gone through the filter of a dark camera. But from time to time they come to us in the most brutal way: counting those who lived it. The memoirs of Marcelino Bilbao (Alonsotegi, 1920 – Poitiers, 2014) show us that the Basques have our flesh in the human massacre caused by the Nazi fragments. His nephew, historian Etxahun Galparsoro, has collected the most outstanding testimony in the history of Bilbao in Mauthausen. Survival memories of a Basque deportee (Critique, 2020).

The deportees of Hego Euskal Herria have not received official recognition in all these years and, once again, it has been the citizens who have promoted initiatives to remember them. Unfortunately, the majority of the deportees are already dead, and representatives of Basque public institutions arrive late in the window of this round trip

The history of Basque deportation is a great forgetting, as the Holocaust is a strange drama for most Basques of war beyond borders. But the two conflicts that have occurred on both sides of the Bidasoa, the Spanish Civil War and the Second World War, have the same root: fascism. And one of his cruellest faces was Mauthausen, the concentration camp where more Basques were deported by the Nazis.

On 5 May, it is 75 years since the liberation of this space by the Allied troops. In total, some 120,000 people were destroyed, and since 1946 an emotional act in memory of the victims who have passed there has been celebrated each year. It is the largest internationalist and anti-fascist concentration in Europe. This year, thousands of people from different countries waited for an important anniversary, but the crisis caused by COVID-19 has forced to suspend the program and virtual pay tribute to the deportees on 10 May, organized by the Austrian Committee of MKÖ Mauthausen.

“Mauthausen embodied the denial of our humanity. What has happened forces us to act responsibly, not to forget it,” said the President of the European Parliament, David Sassoli, in a solemn video. It is our responsibility, therefore, not to forget it.

On 19 August last year the General Gazette of Spain published a list with the names of the Republicans killed in Mauthausen, which included 89 people from Álava, Bizkaia, Gipuzkoa and Navarra. But memorialist groups and new research indicate that victims are many more: Between 1941 and 1945, at least 253 people from Hego Euskal Herria were deported to Nazi concentration camps, most to Mauthausen, and half did not return alive. Despite all this, the list remains complicated, as there are no names of citizens of Lapurdi, Behe Nafarroa and Zuberoa, among others, of Iparralde.

.jpg)

This weekly has found in the database of the French Foundation for the Memory of Deportees names of dozens of Basques: Baiona, Bokale, Ainhoa, Senpere, Maule, Hendaia, Aldude, Gixune… in almost all the villages there are Basque deportees. In addition to the above, those who suffered deportation in the Basque Country could be more than 600 people.

But the exact amount is not the most important thing, but there are many, too many.

The deportees of Iparralde received official recognition from the State in their day, but those of Hegoalde have not had it for all these years, and once again it has been the citizens who have promoted initiatives to remember them, such as that of the Alazne College of Barakaldo, which has proposed the placement of stolpersteine plates on the ground in honor of the Barakaldeses deported by the Nazis. Unfortunately, the majority of the deportees are already dead, and representatives of Basque public institutions arrive late in the window of this round trip.

How did they end up in the concentration camps?

Abandoned at birth by the Nervión River, hence by the name of Bilbao, Marcelino had a hard childhood in the abyss of the mines of Bizkaia. During the 1936 War he was in Republican battalions and, like many others, France was exiled. After fighting with the French army against the Germans, he ended up in Mauthausen, Austria, in the hands of the Nazis. How did he get there?

In February 1939, when the exodus of half a million people from Franco crossed the Catalan Pyrenees, including thousands of Basques, a long chain of extraterrestrials were penultimate steps. First they were transferred to the “boarding” beaches, many were later locked in Gurs, a few kilometers from Zuberoa.

The French authorities did not want to be exiled in their territory, but when Hitler invaded Poland and the hexagon declared war on Germany everything changed. Then, the Spanish Republicans, including the Basque exiles, and the people who dominate their colonies, put them on the front line to be the grass of the Germans tanks. The Euzkadi Government, in exile, preferred to send its compatriots to the front rather than to have massive emigration.

Like Marcelino, most of them went to the Foreign Workers Companies and fortified the Maginot line, a gigantic network of defence infrastructures built on the border between Germany and France, until in May 1940 the German Wehrmacht started a rapid offensive and in a few weeks occupied the Netherlands, Belgium and France, capturing the centres (STAL1).

In these prisons, Spanish Republicans were initially treated in the same way as other prisoners. But the situation changed radically with the visit of the minister of the Spanish Government, Ramón Serrano Suñer, to Berlin in September 1940. The following day, the Security Office issued the Fuehrer's order that from then on the Spanier would cease to be prisoners and send them to concentration camps. They became political deportees. There is no concrete evidence of the Franco Government’s attachment to this decision, but attorney Sophie Thonon-Wesfreid has collected hundreds of documents demonstrating the direct involvement of Serrano Suñer, including letters to the German ambassador, saying that “they didn’t care” what the Nazis would do with them.

Thus came the convoy of Marcelino Bilbao to Mauthausen Station on December 13, 1940, in the middle of snowfall. Open the door and Raus, raus! Raus, raus! (out!) They heard the SS of the Nazi paramilitaries. It wasn't the first and it wasn't going to be the last time.

“This is what is going to happen to you”

“On that bright night we cross the village surrounded by dogs and SS. In the houses people slept quietly, but let it be clear: we went with them. A few years later, those citizens said they did not know what was going on…”. Situated in the time of Austria annexed by Germany, Marcelino learned what the hell of Mauthausen is. It was one of the toughest fields in the Reich, in particular grade III.

The industrial gas chambers, so well known in our imaginary, had not yet spread, and the bulls or servants doing the dirty work of the SS mercilessly killed many of the prisoners by shocks and fire. But most of the deaths were caused by illness, lack of hygiene, cold in the Alps, extreme hunger and unbearable work: the final goal of the enclosure was to “kill the prisoners,” who all had to end up having dinner on schedule.

Shortly after arriving at the Alonsotegi compound, one of the guards hit him with a peak, because he did not understand an order. Soaked with blood, with nothing to heal, he barely survived the isthmus: “But in Mauthausen it was not worth saying ‘I can’t get up!’ Or you stood up or liquidated... Raus, raus!

ONA.jpg)

The deportees were forced to undergo a “quarantine” locked in terrible conditions, so that in that interval they could be erased as individuals, submerged and turned into numbers. Marcelino Bilbao became a German prisoner 4628:Sechsundviersig achtundwanzig.

After the first night they received a visit in the barracks. “A human being who was in the bones entered almost powerless, looked like a skeleton.” “Look at me, don’t you know me?” he asked the Basque. And he said no. Angel Elejalde was a bilbaíno, with whom he had been in front six months before: “He had his eyes sunk, his body without meat and a filthy coat hanged from his neck with a rope. It was shrunk by the cold and had two pieces of wood on the feet, which were so bent on walking.” That scene had been stuck to her forever, “this is what’s going to happen to you,” her friend told her.

The snake that expands and recreates

On the train of August 6, 1940 came the first Basques from the Stalag of Moosburg, among them several anarchists from Mendavia and Ribaforada, but still more would arrive in balance until the end of 1941. Most of them died in the Gus camp, three kilometers away. This space was complementary to Mauthausen, a universe of dozens of fields around the largest concentration camps, to which they never returned: “Alles kaputt,” Marcelino warned.

“They tended me between two and started putting the dead, well bent, to cover everything except the head … They put a cap on my face so I didn’t notice that I was alive, in a minute I was sleeping”

Mauthautsen was divided into two areas. An exterior, surrounded by faces and surveillance towers – in which were the administrative buildings and for the SS, as well as the quarry –; the second, interior, closed with an electrified barrier and with the barracks of the prisoners. It was a kind of snake that spread throughout the day to do the quarries and laughed at night. Given that the concentration camps were not fixed areas, they were monsters who were constantly transformed and moved, now an esplanade for more prisoners, now a furnace for human incineration… Spanish Republicans, for example, in a few months raised the granite wall that would make them more prisoners from their hands.

In a territory without hope, the only domestic law was to extend the duration. Marcelino was helped by two things: football and smuggling. Surprisingly, they had permission to play football – those who had the strength to do so – and, as he was the head, he ended up playing on the Austrian team, which led him to obtain the sympathy of several officials in the concentration camp. It was also accidentally introduced into the smuggling network, enabling him to obtain small advantages that endangered his skin. One thing was clear: no one survived the rules. They had to break to get and keep food.

But despite that, our protagonist had to spend the best moments. For a long time he worked in the granite quarry, the heart of Mauthausen. There, every day, they had to climb the “stairs of death” that became a slaughterhouse of the concentration camp, with a block of stone on top: “And he who couldn’t shoot stayed there. The goal was to make us suffer.”

One day, while working in a field above the quarry, Marcelino got sick, trembling, unable to sustain himself. Her friends hid her among the corpses of Jews who had just died in the heat of the corpses: “They tended me between two and started putting the dead, well bent, until I covered everything except my head … They put a cap on my face so I didn’t notice that I was alive; in a minute I was asleep.”

Dr. Aribert Heim, favorite

One of the greatest cruelties of the Nazis was the use of prisoners for experiments. In Mauthausen, Dr. Aribert Heim did his own and five, and the testimony of Marcelino Bilbao in this book is key to prove it, as it was his bunny. He never knew what the goal of the injections he received was, perhaps to synthesize vaccines for German soldiers,” Galparsoro explains, but Marcelino was completely deformed and left a lifeline mark.

After that they went to the Russian area, where there was more muselmann. They called those who, through hunger and tiredness, had lost the ability to react to orders. Marcelino had become one of them. One day he found himself in a row. “In the end there were two Germans waiting, they beat the sick as we advanced and drowned him in a kind of manger (…) All this happened next to us and we accepted him without moving.” He was finally saved because a friend who was in the ward had recognized him.

“In the end there were two Germans waiting, they beat the sick as we advanced and drowned him in a kind of manger (…) All this happened next to us and we accepted him without moving”

But the worst for him was not hunger or cold, the worst was fear, which paralyzed the person until he was martyred if needed.

“NN” prisoners: they arrive resistant

Starting in 1942, other people began to reach Mauthausen. Until then the Nazis had transported entire collectives in convoys of scientific friends: first the Poles, then the Spanish Republicans, then the Russian Jews… “Entering large groups was a disgrace – Marcelino said – because everyone was trying to kill them.” But that year, in addition to the trio of stripes, small groups identified with the strange letters “NN” began to appear.

Nach und nebel (night and fog) were resilient and detained by the decree of the Civil Guard of Huelva. When Hitler broke the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact and attacked the Soviet Union, the actions of communist resistance multiplied in the occupied territories. The NN Decree established a legal framework to secretly respond to and make any political opposition disappear. Gestapo and collaborating police raided hundreds of people and killed or deported them to the concentration camps in Germany without giving any information.

Among them, of course, there were also Basques, who participated in armed groups or escape networks. Many of them were from Iparralde, many from Hegoalde, and soon a special relationship emerged among them. Not only to Mauthausen's, but to other known concentration camps: Dachau, Buchenwald, Auschwitz, Ravensbrück… In the latter case, several women from the Basque Country were found.

The Ravensbrück camp was very important for the German war industry: they used the hands of women and children to make war material, but these slaves showed enormous courage and organized sabotages, succeeding in destroying many of those weapons, as explained to us by the Catalan prisoner Neus Catalá in his novel Un cel de plom (Ash Sky).

The situation that the newly deported people found in Mauthausen was very different. The Nazis increasingly needed the labour force of the prisoners and, as of April 1943, reorganized the network of concentration camps with capitalist logic, trying to bring the maximum return to the prisoners. Thus, it became a transit point for Mauthausen, from where they began to dispatch the human merchandise to other smaller areas. This shift in perspective, and the experience of veterans, resulted in a decrease in the number of deaths among Spanish Republicans.

Marcelino and his colleagues saw entire families in Yugoslavia arrive at the convoys: “They were fooled, saying they were going to shower. And we were just a few meters away, but the Germans didn't hide anything from us, they were convinced we couldn't survive."

However, the fate of the Jews did not change: for some time they had put in the basement of the prison a small gas chamber capable of accommodating 120 people to exterminate them with Zyklon B. Marcelino and his colleagues saw entire families in Yugoslavia arrive at the convoys: “They were fooled, saying they were going to shower. And we were just a few meters away, but the Germans didn't hide anything from us, they were convinced we weren't going to survive."

From Liberation Day to Oblivion

Marcelino spent the last year in the Ebensee camp. It was already clear that Germany was going to lose the war and started organizing prisoners in order to resist the Nazis deciding to kill them all. Remember that on the day of liberation there was a “bright sun”, but it counts without drowning how the prisoners killed the few guards and goats left one by one, until some were put alive in the incineration furnace. “These extreme situations cannot be analyzed according to current values or ideas,” Galparsoro warned.

.jpg)

After the experience, it is surprising that the Republican deportees were left at the end of the war, both because of the lack of knowledge and indifference of the American soldiers who arrived in the camp and other organizations – Marcelino showed more than once its resentment, because in the delegation of the Government of the Euzkadi of Paris “they did not want to know anything”. He ended up in Châtelleraute (Aquitaine), where he lived with the family of José Mari Agirre, an Irundarra who had been a friend and fellow prisoner.

This story has brought face, shadow and light to the barbarism of Mauthausen; and now we Basques cannot say that we do not know what happened.

The data:

600

Around the Basques they can be the ones who were deported to the Nazi concentration camps between 1940 and 1945. According to a study carried out for the Gogoa Institute of the Basque Government, those in Hegoalde were 253 – almost half have been eliminated. For a full view, ARGIA has also counted on the database of the French Deported Memory Foundation, and has found at least 355 names, many of them taken to Buchenwald and Auschwitz.

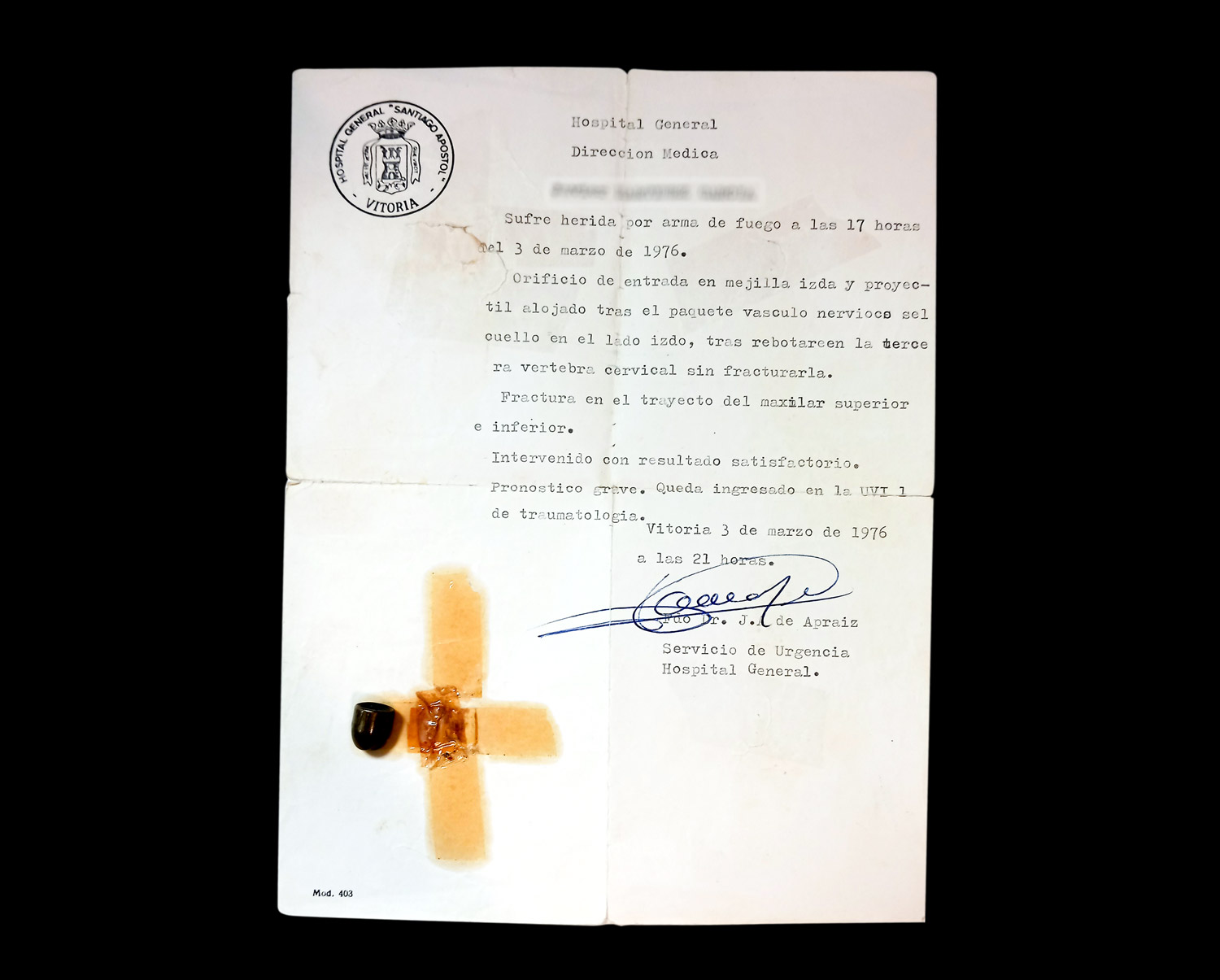

They gave him the number 4628 (photo: Etxahun Galparsoro Archive)

Simonne Lelouch

The Holocaust has a name in the Basque Country and is a woman's name: Simonne Paquita Lelouch. It was gassed at Auschwitz on 12 September 1943. It is believed that this is the only known case of this kind – apart from the massacre of foreign Jews who took refuge on the coast of Lapurdi.

The Nazis began applying the Endlösung der Judenfrage in 1942, "the last solution of the Jewish case", and murdered Lelouch for being married to the son of a group of Polish Jews. The City Hall of Donostia-San Sebastian has recently recognised him as a hidden victim, after which he has been sentenced to prison.

Bilbo Hari Gorria dinamikarekin ekarriko ditu gurera azken 150 urteetako Bilboko efemerideak Etxebarrieta Memoria Elkarteak. Iker Egiraun kideak xehetasunak eskaini dizkigu.

33/2013 Foru Legeari Xedapen gehigarri bat gehitu zaio datozen aldaketak gauzatu ahal izateko, eta horren bidez ahalbidetzen da “erregimen frankistaren garaipenaren gorespenezkoak gertatzen diren zati sinbolikoak erretiratzea eta kupularen barnealdeko margolanak... [+]

1976ko martxoaren 3an, Gasteizen, Poliziak ehunka tiro egin zituen asanbladan bildutako jendetzaren aurka, zabalduz eta erradikalizatuz zihoan greba mugimendua odoletan ito nahian. Bost langile hil zituzten, baina “egun hartan hildakoak gehiago ez izatea ia miraria... [+]

Memoria eta Bizikidetzako, Kanpo Ekintzako eta Euskarako Departamentuko Memoriaren Nafarroako Institutuak "Maistrak eta maisu errepresaliatuak Nafarroan (1936-1976)" hezkuntza-webgunea aurkeztu du.

Tafallan, nekazal giroko etxe batean sortu zen 1951. urtean. “Neolitikoan bezala bizi ginen, animaliez eta soroez inguratuta”. Nerabe zelarik, 'Luzuriaga’ lantegian hasi zen lanean. Bertan, hogei urtez aritu zen. Lantegian ekintzaile sindikala izan zen;... [+]