Malaria vaccine: How will it affect the fight against the disease that kills 240,000 children every year?

- The World Health Organization (WHO) has given the green light this Wednesday to the first vaccine against the malaria.Representantes of experts and organizations around the world have considered a very important step for children's health.

The malaria vaccine is a very important step towards eradicating malaria that kills tens of thousands of children each year. In Africa, for example, they cause 260,000 deaths and about 400,000 deaths worldwide, of which 240,000 are children.

Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, of the World Health Organization (WHO), has assured that this is a "historic" moment and that every year "will save the lives of thousands of young people". “We have been waiting for an effective malaria vaccine for a long time and now, for the first time, we have a recommended vaccine for general use.”

Specifically, the WHO has recommended the use of this vaccine in children in sub-Saharan Africa, where there is an intermediate or high transmission of the parasite Plasmodium falcicarium. This parasite passes through mosquitoes. The vaccine has been manufactured by the pharmaceutical company GlaxoSmithKline, a listed multinational based in Brentford, in the United Kingdom. Mosquirix will be your trade name.

Ghana, Kenya and Malawi were tested in 2019 to 90% of children who did not sleep under the veil of mosquitoes, and the main result is that the number of serious cases causing death has been reduced by 30%. According to the WHO report, the vaccine is “cost-effective” and easy to produce and store. It needs four doses to achieve this effectiveness.

Disease related to inequality

Malaria remains one of the main causes of the high infant mortality rate in the countries of central and southern Africa and is widespread in America – the Europeans led it to conquer that territory. Europe, however, was declared "malaria-free" by the WHO in 2016.

In southern Europe, it was endemic for a long time and until the twentieth century the population suffering from malaria was not poor, to the point of evicting the populations of the wetlands. Although the use of hazardous insecticides became radicalized, in the 1990s it was re-expanded. In any case, there are hardly any cases today as a result of preventive measures.

Thus, most malaria deaths are attributed to inequality. In fact, it can be avoided if some basic training and prevention measures are taken, but for many African citizens who do not have resources and live in precarious living conditions this is impossible. Madrid physician Pedro Alonso, director of the World Malaria Programme, has acknowledged that: “Those who die are poor, it’s a disease of inequality, it’s people who don’t have access to some basic instruments, such as a mosquito net rubbed with an insecticide.”

Twenty years after mass programmes for the use of mosquito nets began in Africa in 2000, and despite the fact that they have partly prevented the transmission of malaria, difficulties in access to the entire population mean that flying insects with deadly parasites remain a nightmare in many homes. That is why the WHO approved vaccine is good news for those who fight the disease.

EAEn BAMEa (famili medikuen formazioa) lau urtetik hiru urtetara jaistea eskatu du Jaurlaritzak. Osakidetzaren "larritasunaren" erantzukizuna Ministerioari bota dio Jaurlaritzako Osasun sailburu Alberto Martinezek: "Ez digute egiten uzten, eta haiek ez dute ezer... [+]

Sare sozialen kontra hitz egitea ondo dago, beno, nire inguruan ondo ikusia bezala dago sare sozialek dakartzaten kalteez eta txarkeriez aritzea; progre gelditzen da bat horrela jardunda, baina gaur alde hitz egin nahi dut. Ez ni optimista digitala nauzuelako, baizik eta sare... [+]

Berrogei urte dira Euskal Herrian autismoaren inguruko lehen azterketak eta zerbitzuak hasi zirela. Urte hauetan asko aldatu da autismoaz dakiguna. Uste baino heterogeneoagoa da. Uste baino ohikoagoa. Normalagoa.

Itxaron zerrendak gutxitzeko Osasunbideak hartutako estrategiak gaitzetsi ditu Plataformak

Endometriosiaren Nazioarteko Eguna izan zen, martxoak 14a. AINTZANE CUADRA MARIGORTAri (Amurrio, 1995) gaixotasun hori diagnostikatu zioten urtarrilean, lehen sintomak duela lau urte nabaritzen hasi zen arren. Gaitz horri ikusgarritasuna ematearen beharraz mintzatu da.

La bajona kolektibo kide Heiko Elbirak salatu du psikiatriak zisheteroarautik aldentzen diren erotikak kontrolatu nahi dituela.

Barakaldoko ospitaleko larrialdi zerbitzuan sufritzen ari diren "saturazioa larria" dela ohartarazi du sindikatuak. Pazienteak korridoreetan artatu dituztela eta krisia kudeatzeko "behar adina langile" ez dagoela salatu du. Errealitate horren aurrean... [+]

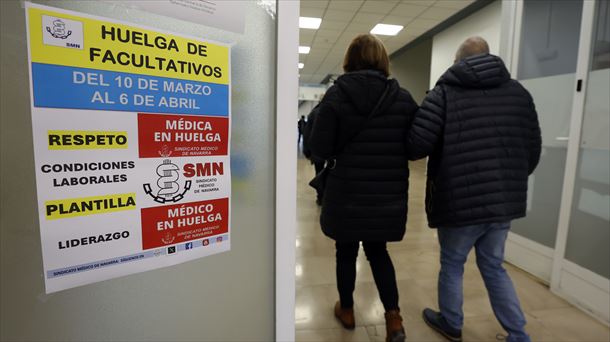

Astelehenean abiatu da sindikatuak deitutako greba eta apirilaren 6 arte luzatuko da. Lan-gainkarga salatu eta baldintzak hobetzeko eskatu dute, baita mediku egoiliarrei karrera profesionala aitortzea ere.

Alberto Martinez Eusko Jaurlaritzako Osasun sailburuak argi dio: ez ditu mediku euskaldunak aurkitzen, eta euskarazko osasun arreta ezin da bermatu mediku egoiliar (formazioan dauden espezialista) gehienak kanpotarrak direlako. Mediku euskaldunak bilatzea perretxikotan joatea... [+]

Soco Lizarraga mediku eta Nafarroako Duintasunez Hiltzeko Eskubidea elkarteko kidearen ustez bizi testamentuak heriotza duin bat eskaini eta familiari gauzak errazten dizkio.

Gauez ia aste osoan ateak itxita izaten ditu Donibane Lohizuneko osasun zentro horretako larrialdi zerbitzuak. Herri Berri udal oposizio taldeak deituta, mobilizazioei ekin diete herritarrek eta jadanik 3.000 sinadura bildu dituzte zerbitzu "iraunkor eta eraginkorra"... [+]

Bizilagunek "egia eta politika" merezi dutela adierazi dute, oraindik konponbiderik bilatu ez zaizkien arazo ugari edukitzen jarraitzen baitute. Ikasketei eta osasun arretari loturiko arazoak nabarmendu dituzte.

Udaberri aurreratua ate joka dabilkigu batean eta bestean, tximeletak eta loreak indarrean dabiltza. Ez dakit onerako edo txarrerako, gure etxean otsailean tximeleta artaldean ikustea baino otsoa ikustea hobea zela esaten baitzen.