Clothing belt, you see curves in the world economy.

- The international media are multiplying the news that warns of the risk of a new economic crisis. However, it is not clear what they are based on. To better understand the latest fluctuations in the financial world, in the following lines we will try to explain what the yield curve is.

The economist and federal coordinator of UI in Spain, Alberto Garzón, has been in charge of explaining this concept in a thread hanging on Twitter.

These days the G-7, the club of seven of the richest countries, meet in Biarritz. One of the most discussed issues in this and other fora is an impending crisis. What are the chances of another economic crisis? (THREAD 👇):

— Alberto Garzón🔻 (@agarzon) August 23, 2019

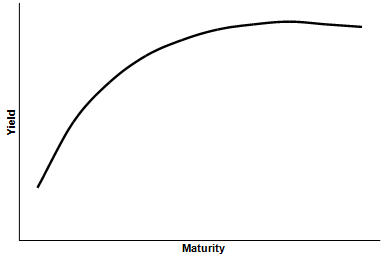

Garzón explains that the economy is not an exact science, so it is not always possible to predict when crises will happen. But there are some indicators that can help make these forecasts. One of them is the performance curve: this graph shows the benefits of financial products issued by states or companies, and in view of what the URL0 shows, you can see signs of crisis.

“If a country wants to be indebted to make an investment, it can issue financial securities. The curve refers to this possibility,” explains Garzón. States, for example, issue securities that allow them to receive money immediately in exchange for an interest payment commitment to investors who have paid for them in the future. These are contracts that vary according to quantity, duration and performance.

"When a state issues securities, it does so by auction. The State sells X securities and the price is obtained from the auction. If there are many buyers, the price will be higher (and the yield is low). If there are few buyers, the price will be low (and the yield high),” explains Garzón. “Return”, i.e. the interest to be received by the purchaser of the securities.

Not all titles are the same: In the Spanish State, for example, returnees in months are called “Letra”; those of two, three and five years are called “Bono” and those of ten, fifteen or thirty years are called “Obligation”. And, in principle, longer-term securities offer the highest returns, as investors expect more money to leave the money longer.

Under normal conditions, therefore, the performance curve should look like this.

But the market situation is not always the same. At times of low confidence, investors are starting to purchase long-term securities, especially in some individual countries. “The safest countries are those of the United States or Germany, because they cannot touch bankruptcy.”

Investors looking for secure securities are therefore betting on the long term and on the rich countries, which means reversing the yield curve: a strange phenomenon, as it shows that short-term securities offer a higher return than long-term ones, as in these seconds too many investors have accumulated at any given time.

“At the moment, there are about twenty countries that have the reverse curve and that of EE.UU stands out,” the economist explained. “Since 1955, every time the performance curve is reversed, there is an economic recession, sometimes in a few months and others with a delay of one year. If this dynamic is maintained, the economic crisis in the United States would be assured in the short term,” he said.

In the case of the Spanish and French States, also in Germany, the curve is the other way round. The titles are zero or negative. “That means investors are paying for leaving money,” says Garzón. The cause? The central banks' commitment to cheap money, for the benefit of the large banks. “This allowed to explain the bubbles that have been produced in financial assets and, according to some economists, the yield curve may be the other way around. But it can be said that there is a lot of lack of confidence and a lot of fear of the crisis,” according to Garzón. “Investors are getting ready because there are alarms to another crisis and the prophecies that self-claim in the financial system don’t help much.”

For UI members, governments and central banks do not have an easy solution: “Over the past ten years, all the bullets have been spent on monetary policy and to give reason to the heterodox economists would be to move on to a serious fiscal policy. (…) The limits of monetary policy are becoming apparent, even at the sacrosanct seat of ordoliberalism. The German minister wants a tax policy and the Bundesbank says no.”

Garzón recalled an economist John Maynard Keynes' concept to describe the current situation: “Liquidity trap.” In other words, if you do not see the possibility of charging higher interest, it is the same money that is injected into the system, as the European Central Bank has done in recent years, because the markets are saturated and does not serve a monetary policy.

As an alternative, Garzón proposes that the European Central Bank should finance direct economic promotion programmes to avoid speculative situations arising through the provision of financial money to banks.

Pazienteek Donostiara joan behar dute arreta jasotzeko. Osasun Bidasoa plataforma herritarrak salatu du itxierak “are gehiago hondatuko” duela eskualdeko osasun publikoa.

PPrekin eta EH Bildurekin negoziazioetan porrot egin ondoren etorri da Ahal Dugurekin adostutako akordioa. Indar politiko honek aitortu duenez, maximalismoak atzean utzi eta errealitateari heldu diote, errenta baxueneko herritarren aldeko akordioa lortuta.

.jpg)