"Languages and gender are not apart, never"

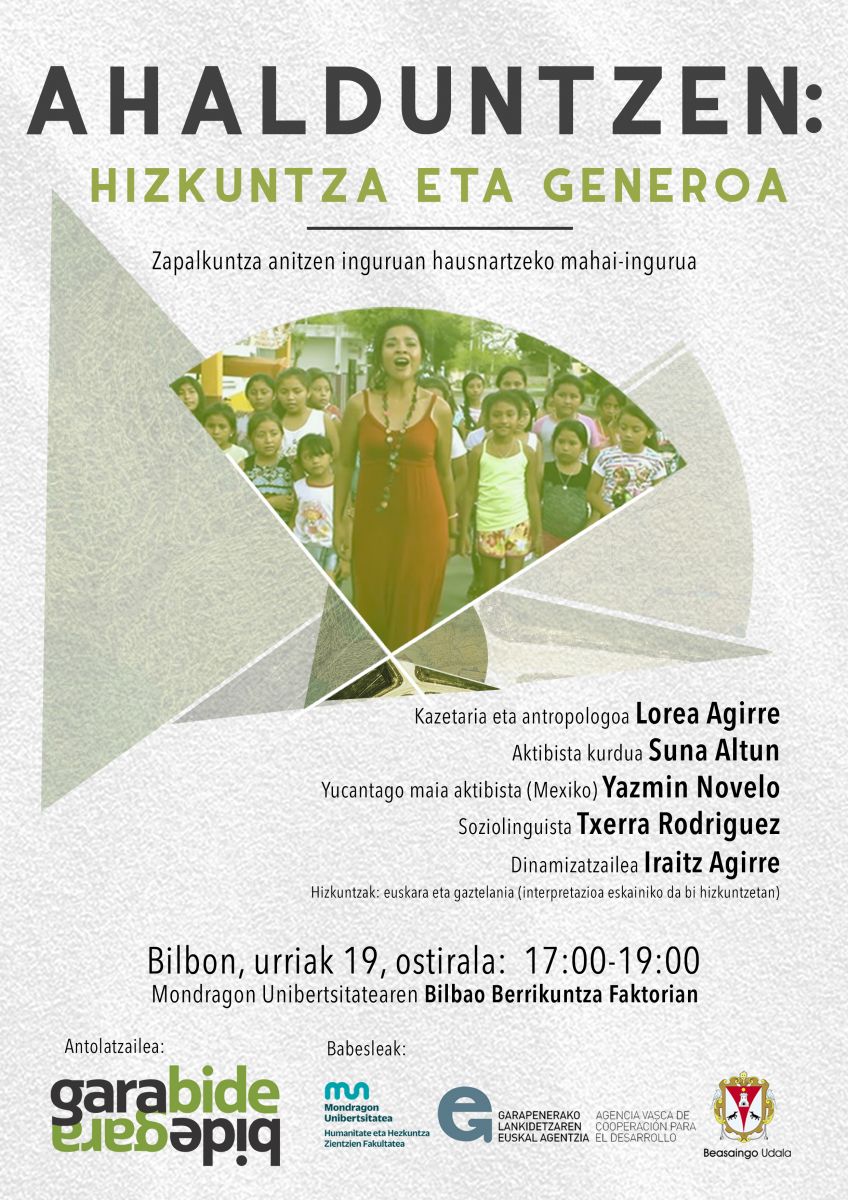

- The working sessions (in the morning) and the round table (in the afternoon) that Garabide organized last Friday at the Bilbao Innovation Branch of Mondragon Unibertsitatea under the title Empowerment: language and gender, have met the expectations and are intended to be the starting point of a permanent dynamic to connect linguistic activism and women’s empowerment. In this chronicle we will give an account of the work of the round table.

Lorea Agirre ended her speech with the phrase that we have included in the title of the article, before starting with the requests and questions. A round phrase that summarises very well the experiences and opinions expressed at the round table.

Under the leadership of Iraitz Agirre, four rapporteurs representing the linguistic communities of the three continents met around the table: The Kurdish activist Suna Altun, the Mexican activist Yazmin Novelo in favor of the Mayan language, and among the Basques the socio-linguistic and anthropologist and journalist Lorea Agirre, Txerra Rodriguez. Just as when we looked from the lock of an old door, we had the opportunity to approach the situation of women working for the revitalization of minority languages in different parts of the world, as happens on rare occasions, because from their own lips we hear where and how the oppression of gender and language crosses.

To begin with, IRAITZ Agirre gave them a point where everyone could write a verse in rhyme and free tone: “Do we use hegemonic language and minority language the same as women and men?” Everyone answered no, but the nuances that emerged in each case were a reflection of different realities.

The Kurdish activist Suna Altun then began her individual intervention and informed us of the situation of the Kurds living under Turkish rule. He began his presentation with the motto Jin, Jîyan, Azadë, well known among the Kurds, adding a word and with the renewed motto Jin, Jîyan, Azadì, Ziman (in Basque “Woman, Life, Freedom and Language”). It focused on the linguistic status of women and on the goals that Kurdish women have to change the situation, as well as on the struggles they have in place to achieve them. To conclude his intervention, he pointed out three aspects to be prioritized: the need to give greater value to language in education and in all public areas, the alignment of strategies for the revitalization of the language and the empowerment of women and that the responsibility for the transmission of the language at home be both of the mother and the father. In line with this last suggestion, Suna Altuna referred more than once to the term “mother tongue”, instead proposed “home language” and even mentioned the use of “first language” in the contributions of the public or the need for other terms, for example, for cases in which the domestic language does not correspond to the language of schooling.

We turned around the world and then jumped into Mexico. Yazmin Novelo, speaking maia and activist language of Yukatango, told us the reflections of the workshops with 22 women from the community. Among other issues, they tried to answer the following question: “To what extent does linguistic activism drive a more just and equitable world?” The group of women reached two conclusions: on the one hand, linguistic activism must be a tool to build a lifestyle with multiple ways of being in the world and, on the other, through linguistic activism, spaces for social justice must be sought. In Novelo's words, the unequal power relations in society force us to learn to jointly confront the oppressions shared by women and minority languages, in short, linguistic or gender hegemonies are also cultural hegemonies, as our goal cannot be limited to recovering the areas of use of minority languages or guaranteeing the presence of women in the corresponding spaces.

The Basques took the witness below and Txerra Rodríguez focused his intervention on the data. To start with, he wanted to deal with the following data: According to the data declared in Euskal Herria, women and men are in equal conditions of knowledge, but in the use of the street women use more Euskera and in Euskaltegis, and women also predominate in conversation people.

Women use Euskera more in all age groups and in Euskaltegis and in conversation people women also predominate

After putting this data on the table, he presented the conclusions of some investigations and told us that the linguistic identity of the mother is heavier than that of the father. On the other hand, studies show that women start learning the main language later, but forget their original language faster. First of all, of course, the doubts became more evident and so summarized by Txerra Rodríguez: on the one hand, the revitalization of the Basque Country has been left largely at the expense of women and children, that is, of the groups with less power in society and, finally, it was asked: if the use of a language is feminized, does it not automatically devalue itself?

The last of the interventions was that of Lorea Agirre, brief but fruitful. As the title of this chronicle is his mention, to summarize his intervention we have gathered here other quotes from Lorea that have been the topic of title: “The relationship between languages is a relationship of power. Language and gender are necessarily mixed,” he stressed that from what we are we do everything we do, both in the sexual system and in language. In this sense, he said that “I am the same person, not 60% feminist and 40% Euskaltzale, to name a few militanas… everything goes at once.” In addition, with regard to empowerment, he pointed out that “we are not empowered in one thing, we are empowered as people, all things are united” and, as an example of this, Euskaraldia considered as an exercise in empowerment. Finally, he left on the table that power relations can be dismantled insofar as they are built and called to act collectively in it.

In this brief chronicle it is not possible to collect all that the two-hour programme gave, but far from being an isolated activity we put them in a broader context and, for the future, have been a starting point for deepening linguistic cooperation projects. We will continue to open spaces to get to know each other, listen to each other and exchange experiences as different oppressions lead us to different strategies of empowerment.

Lagun asko sumatu dut kezkatuta euskaldun gero eta gutxiagok ahoskatzen duelako elle-a. Haur eta gazte gehienek bezala, heldu askok ere galdu du hots hori ahoskatzeko gaitasuna, idatzian ere nahasteraino. Paretan itsatsitako kartel batean irakurri berri dugu: altxorraren biya... [+]

570.000 familiak euren haurren ikasgeletako hizkuntza nagusia zein izango den bozkatzeko aukera dute martxoaren 4ra arte: gaztelera edo katalana. Garikoitz Knörr filologoaren eta euskara irakaslearen arabera, kontsultak "ezbaian" jartzen du katalanaren zilegitasuna... [+]

Iragan urtarrilaren hondarrean, Bretainiako lurraldeko bi hizkuntza gutxituei buruzko azken inkesta soziolinguistikoaren emaitzak publiko egin zituzten bertako arduradunek. Haiek berek aitortu zuten harriturik gertatu zirela emaitzak ikustean. Hain zuzen ere, egoerak eta... [+]

Oinarrizko maia komunitateko U Yich Lu’um [Lurraren fruitu] organizazioko kide da, eta hizkuntza biziberritzea helburu duen Yúnyum erakundekoa. Bestalde, antropologoa da, hezkuntza prozesuen bideratzaile, eta emakumearen eskubideen aldeko aktibista eta militante... [+]

Korsikako legebiltzarkideek ezin dute Korsikako Asanblean korsikeraz hitz egin, Bastiako Auzitegiaren 2023ko epai baten arabera. Ebazpen horri helegitea jarri zion Asanbleak, baina debekua berretsi du orain auzitegi berak. Epaiak tokiko beste hizkuntzei eragiten diela ohartarazi... [+]