We don't realize

- The effects of the heat waves and the drought we have suffered this summer may lead to a social leap in the awareness of climate change to “believe what we know”, as Jean-Pierre Dupuy said. But that jump, to address the evolutions that await us, is that big enough?

Five months ago, in April, an article published in the newspaper Berria went quite unnoticed, especially here in the Northern Basque Country, in the midst of the French presidential elections. In this article, Iñaki Petxarroman described the climate situation in Euskal Herria, with a degree and a medium of global warming, or following the hypothesis of a three-degree warming.

When I read these descriptions, the first thing came to mind: we don't realize it. Certainly. We do not realize the changes that await us in our territory, in the farms, jungles, mountains and coasts of the Basque Country.

It was hard for me, for example, to realize that oaks and beasts, within a few decades, will not survive in most of the places there are now. Aralar or Irati, or Mount Faalegi of Biriatou, closest to my corner, with its northern slope covered by beech trees, children today will not be able to see the same appearance at age 50, with dry summers and hard evenings of 40 and more degrees. And in my orchard, the acorns that germinate ten whole years will not grow as much as the 80-year-old oak that it has produced.

We may think that jungles are not the first necessary in comparison to water and/or food, as they are less “functional”. But oak and beech, our lifelong trees that have lived in our mountains since prehistory, are a sign of a tremendous evolution that will reach the end of its history in our territory. Therefore, we do not realize and, for example, want to replant local trees instead of the old and old pine forests on Mount Larrun, of those who prefer the beech and birch, the temperate summers and those who need water in summer. A very successful choice to plant on Mount Larrun, if we were in 1920, but not today. Much of what has so far been local is not going to be more local, so we haven't yet realized it.

Variability, jet-stream wind and us

Iñaki Petxarroman also explained how different climate zones will move north. Following the A1FI hypothesis of the GIEC or IPCC, if at the end of the 21st century a warming of 5?C is achieved, in the 2060s the ocean climate will disappear completely from the Basque Country, being replaced by the Mediterranean climate mainly towards Bizkaia and Landeta, and subtropical between the two (Gipuzkoa, northern Navarre or Lapurdi).

But with these words, let us not imagine that the times that await us are like today in Greece or Uruguay: the distribution of temperatures and rains will be very different, with more extreme episodes. Among the underlying graphical examples, more than two degrees but with the same distribution, which would be the case (a), will increase variability, case (b), and may also vary the distribution symmetry, further increasing the proportion of days of intense heat in terms of temperature, which shows the case (c). July 2020 or summer this year are concrete examples of the latter case. In terms of rainfall, extreme situations are more frequent: ever-longer droughts and increasingly dense and long rains, suffocating the land and making floods typical.

If this wasn't hard enough, in our latitudes we have another important influence of climate change, the chaotic bluffing of the jet-stream wind trajectory. Jet-stream is a tall wind (about 7000 m) that blows around latitude 60?N, in the north of Scotland or in the latitude of the Norwegian city of Bergen. But it doesn't circulate in a straight line, and it curves north or south.

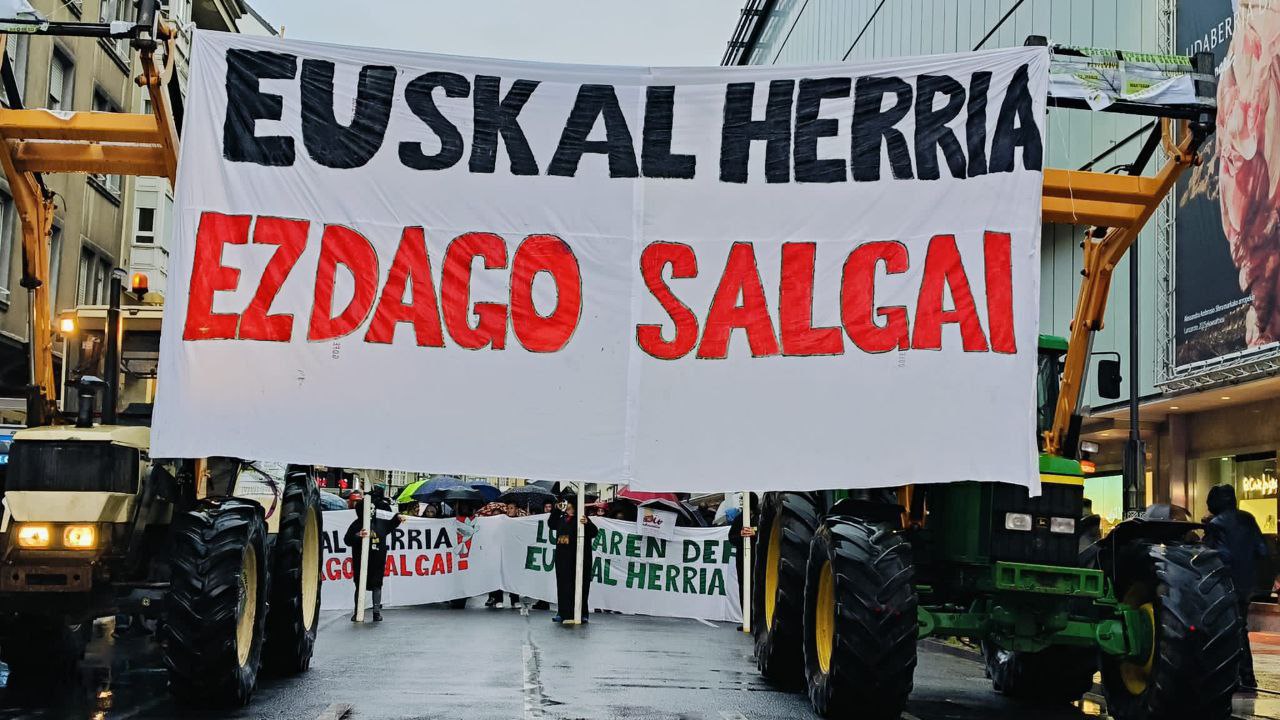

That today, with climate change, these curves open, that is, that the wind current is sometimes moving further north than before, or sometimes flying more than before. Like the trajectory of a drunk, it gets drunk more. When it moves north, it gets extraordinary heat, because the tropical air is absorbed north, and when it moves south the opposite, it gets cold air from the north, as shown on the bottom map. And of course, these curves move around, they don't stop all the time in the same place. So we can have 27?C in the afternoon at the end of March, and if this jet-stream moves south, frost takes a week longer. Or, in summer, sucking air from the Sahara, going from one week to another from 22?C to 42?C. It is clear that under these conditions cultivation becomes more difficult. With late frost, severely damage fruit trees, vineyards, newly germinated bethunew, sunflowers or paws. Also in summer heat strokes strongly press corn (damaging pollination), all vegetables and fruits, and grass to eat. And that, in Euskal Herria, we only produce about 15 percent of our food. There is still a road to sovereignty and the road is becoming more complicated. We are only at the beginning of the problem.

Need for progress

If the perception of climate change were to be commensurate with its consequences, it would feed the headlines of the mainstream media every day. But we don't realize it. In Euskal Herria, especially for being a small people without a State1, we are more interested in our past, whether we are those who seek in the past the essence of feeding our current enthusiasm or arguments to justify our identity as a people.

The fifth centenary of the battle of Amaiur or the first round of the world of Elcano (as Peio Etcheverry Aintchart explained last month), the history of our language, or the endless debates about the political strategies of the last century and their collateral damage.

However, as Jon Maia said recently, the best tribute we can pay to the past is to guarantee a future, to give continuity to history.

Although the road is becoming more complicated, as far as material sovereignty is concerned, there is still room for doing something, and we have nothing left to do. Our beloved corners must survive, as our culture and our personality must survive, even if the climate is hardened. In order to do so, we must understand what tomorrow’s climate will look like.

The beech and birch will be better than in Larrun in Norway, and in our mountains we would have to plant more marojo, chestnuts, cork oak, Madroño, quejigo.

Replace maize with winter bait in the North (wheat, oats, rye) or sorghum, develop ways of working to store more carbon and moisture in the soil and drink from the source of our rich agricultural history, learning from the work of Professor Jakes Casaubon.

The starting point must be clear: hard time is a new normal, things are not as easy as before, but it is not too late to make substantial changes.

(1) I know that this type of verb is not officially accepted, but I didn’t want to write that it looks “to ourselves,” because I don’t see so clear where we are facing this problem.

Bidali zure iritzi artikuluak iritzia@argia.eus helbide elektronikora

ARGIAk ez du zertan bat etorri artikuluen edukiarekin. Idatzien gehienezko luzera 4.500 karakterekoa da (espazioak barne). Idazkera aldetik gutxieneko zuzentasun bat beharrezkoa da: batetik, ARGIAk ezin du hartu zuzenketa sakona egiteko lanik; bestetik, egitekotan edukia nahi gabe aldatzeko arriskua dago. ARGIAk azaleko zuzenketak edo moldaketak egingo dizkie artikuluei, behar izanez gero.

Andrea Velasko dietista eta nutrizionistak elikaduraren bidez menopausiak eragindako aldaketak kudeatzeko zenbait gako eman ditu.

BRN + Auzoko eta Sain mendi + Odei + Monsieur le crepe eta Muxker

Zer: Uzta jaia.

Noiz: maiatzaren 2an.

Non: Bilborock aretoan.

---------------------------------------------------------

Ereindako haziek ura, argia eta denbora behar dute ernaltzeko. Naturak berezko ditu... [+]

Antonio Turiel fisikari eta CSICeko ikerlariak aspaldiko urteetan ez bezala bete zuen Hernaniko Florida auzoko San Jose Langilearen eliza asteazkenean. Zientoka lagun elkartu ziren Urumeako Mendiak Bizirik taldeak antolatuta Trantsizio energetikoaren mugak izeneko bere hitzaldia... [+]