The Basque letter bollers stick and feel

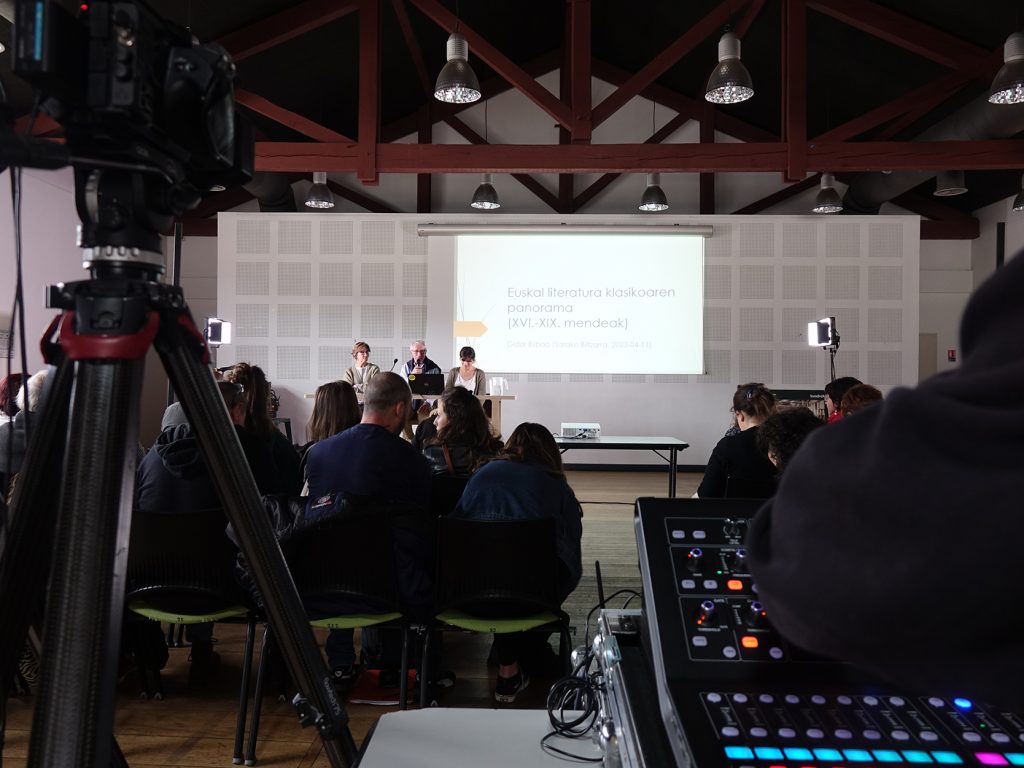

- Lizar Begoña, June Fernández and Eva Pérez-Pons met on 2 December in Izarra (Araba). Under the title Bolleras in the Basque letters, they talked about the words, the silence and the pain that are chosen to designate the chapels, and the lack of referents.

The round table was organised by Sareinak in collaboration with EHGAM in Gorbea. He led the group Amaia Alvarez Uria Sareinak. The Japanese Gepardo (Susa), by Lizar Begoña, took advantage of his work of poetry, Bodies for the Resistance of Eva Pérez-Pons: the essay Bolleras (Lisipe) and Mariokerra, by June Fernández. Essay Nola izan / esan bollera euskaraz (Txalaparta).

Amaia Alvarez has given an introduction to the round table saying that in recent years more and more leaflets are publishing literature and that it is a source of joy.

Selecting words

Álvarez begins to wonder what words are used to say the bolle or what options exist. Give the floor to June Fernández and Marioker. The latter referred to the book Nola esan / izan bollera euskaraz. In fact, this year Fernández and Álvarez have published the book with the editorial Txalaparta. The starting point of the book was Zinegoak. The organizers of Zinegoak asked them to make a dictionary, and so they went on to make a dictionary equivalent to that of Gay Aitor Arana. They soon realized that they would overcome a simple dictionary and prepared for Zinegoak a job that intends to answer the two questions: how to say lesbian in Basque and how to be lesbian in Basque. The initial project ended in the form of a book.

Fernandez explains that among the people who consulted for the book, the word bollera was the most widely used. They consider it a more politicized term (e.g. lesbian), it means a political identity and it is more subversive. However, Fernández points out that the term is not valid for the entire Basque Country. In Iparralde they use gouine. The ‘veterans’ interviewed by Mariokerra have claimed the term lesbian. A listener has also mentioned that does not reject the use of the word lesbian; if the word bollera has a political meaning today, the word lesbian also had that meaning in his day.

For their part, Fernández and Álvarez, in their eagerness to reclaim the game to create new words, explain how the mariokers have proposed the term to complete the glossaries glossary. The two authors of the book are eager to know the path that the term marioker will follow. At the moment, Fernandez finds a Tinder marioker user.

For Eva Pérez-Pons, the word bollera comes from the lesbian and homosexual terms and serves to get out of heterogeneous feminism. Reality considers it a term that serves to change and that has a very broad meaning, that goes beyond genital and sexual desire. Lizar Begoña has also opted for the term bollera, which takes it in a more politicized way than lesbian.

Lesbians, mouths, gouine, has left aside and Álvarez has reflected on what few words related to sexuality are in Basque literature, and has explained that although Mariokerra asks for the book, they have received very few. The issue remains taboo. Begoña has increased her voice in reflection: “We lack references, images, words…”.

Moths and silences

The four speak for a while about what is not said and calm down. Begoña reads the poem Sitsak (without telling you what he meant / died in the womb / like all other sits) and explains what he wanted to say: “Everything that is not said dies in the tummy.” Begoña has tried to empty words and give it a new meaning in her book of poems. Writing for Begoña has been a way of “for how amorphous I have inside”, his free space. Pérez-Pons adds that we have a very binary dictionary, that practices and language do not go together. Fernandez talks about the pains of the bolles, about silence the pains. Begoña and Fernández agree that the creators of Bolleros often transmit in writing what they mean, and not in front.

Presence of pellets in Basque letters

Álvarez starts doing a review in a moment: Itxaro Borda, pioneer, of another generation Kattalin Miner and Danele Sarriugarte, bertsolaris bolleras, youths doing poetry… Comments on the need to discuss the outing (come out of the closet). On the one hand, as was also stressed in the round table, the lack of references in the Basque letters is highlighted, but on the other hand there are difficulties in coming out. Begoña adds a nuance to Álvarez’s reflection: “The creator may think that by going out his work he can receive a restrictive look, that is, we run the risk of reading ourselves by one prism and each creator goes through many things.”

Now that everyone has become more Franciscan than the Pope, it’s worth remembering our unsurpassed classics. There was one in the 17th century, his grace was Arnaut Oienart. And since we can’t immerse ourselves in all his works, today we will praise O.ten youth in... [+]

Aurreko tertuliako galderari erantzuteko beste modu bat izan zitekeen, akaso modu inplizituago batean, bigarren solasaldi honetako izenburua. Figura literarioaz gaindi, pertsonaia zalantzan jartzeko, edo, kontrara, pertsonaiaren testuingurua ulertzeko saiakera bat. Santi... [+]

Astelehen honetan hasita, astebetez, Jon Miranderen obra izango dute aztergai: besteren artean, Mirande nor zen argitzeaz eta errepasatzeaz gain, bere figurarekin zer egin hausnartuko dute, polemikoak baitira bere hainbat adierazpen eta testu.

Martxoaren 17an hasi eta hila bukatu bitartean, Literatura Plazara jaialdia egingo da Oiartzunen. Hirugarren urtez antolatu du egitasmoa 1545 argitaletxeak, bigarrenez bi asteko formatuan. "Literaturak plaza hartzea nahi dugu, partekatzen dugun zaletasuna ageri-agerian... [+]

1984an ‘Bizitza Nola Badoan’ lehen poema liburua (Maiatz) argitaratu zuenetik hainbat poema-liburu, narrazio eta eleberri argitaratu ditu Itxaro Borda idazleak. 2024an argitaratu zuen azken lana, ‘Itzalen tektonika’ (SUSA), eta egunero zutabea idazten du... [+]