Centenarian flu: so far away, so close

- As the coronavirus expands around the world, comparisons between today's and 1918 flu pandemics are multiplying; although the atmosphere is similar, the reality is very different.

The Spanish flu spread throughout the world by the armies of the First World War and became the largest pandemic of the twentieth century. A hundred years later, thanks to the expansion of the mobility of both citizens and goods, the first pandemic of the twenty-first century has also spread in a globalised world. Fear is the main common characteristic.

The disease, known as Spanish influenza, Spanis Flu, Spanish Lady, Grippe Espagnole or Spanish Flu, came to Europe through the United States. Without a war, it would only be a scourge of limited extension. However, thanks to the movement of thousands of soldiers during the First World War, the epidemic spread throughout the world. Thus, between 1918 and 1919, he left millions of deaths.

"The spread of the flu was conditioned to the sine qua non was the Great War," he added. This was taken up by Colombian University researchers Liliana Henao-Kaffur and Mario Hernandez-Alvarez in a study on the pandemic carried out four years ago: "The flu broke out in Brest (Brittany, France) in early April 1918, when the landings of the troops took place in that city, and at the end of the month there were also cases in Italy, as well as among the German soldiers who were in France. In the first part of May, the flu appeared in Spain, Greece and Portugal, and in the second it reached Shanghai and Bombay."

Name of censure

Evidently, Spain was not the source of the flu. During the First World War, it was a neutral country in which local media uncensored reports and information about the disease. Thus, and being the only country that reported the problem, the epidemic became known as the "flu of Spain", with a name "xenophobe and hypocritical", according to Colombian researchers.

The media in Germany, England and France, for their part, concealed information about the flu to "maintain the morale of the armies of the country".

Censorship and lack of resources prevented the investigation of the deadly outbreak of the virus, and most of the victims were young and healthy adults between 20 and 40 years old. High fever, ear pain, tiredness, diarrhea and occasional vomiting were characteristic symptoms of the disease. Most of the people who died in the pandemic suffered from second-degree bacterial pneumonia, as there were no antibiotics.

Millions of deaths

As there were no sanitary protocols for the patients, they were concentrated in small areas not ventilated. At that time, the fabric mask and gauze became known, although totally unnecessary.

In total, in two years, the Spanish flu caused more than 40 million deaths in almost all countries of the world. The exact number of the pandemic, estimated by some researchers at 15 million and others at 100 million, is unknown, but it is currently the largest epidemic recorded in history. In fact, it also promoted the creation of the World Health Organization in 1923, with the intention of dealing with future pandemics.

October 1918 in the Basque Country

In Europe, the flu began to spread between March and April 1918, and most deaths occurred in fall and winter. The following year there was a third, weaker wave on the south coast of the country.

In the Basque Country, on the contrary, there were hardly any cases of influenza in the spring of 1918. The influenza epidemic in Spain occurred between September and December, and it was in October 1918 that the highest mortality was recorded.

There was no third wave, and in the first months of 1919 and 1920 there were only a few casos.El director of the Basque Museum of History of Medicine, Antón Erkoreka, published in the study The Spanish flu pandemic in the Basque Country (1918-19) in 2006 that the flu affected between 50 and 60% of the population and the mortality rate was 12.1%.

Vitoria, soldiers and priests

As has been said, the second wave of influenza in Spain was the most severe of those recorded. Vitoria-Gasteiz had a population of 36,640 and it was at the end of September that the epidemic began in the capital of Alavesa. "It shows very strongly in October; throughout the month of November there are many cases, it extends until the spring of 1919." ERKOREKA pointed out that the flu in Spain particularly affected the young people attending the seminar in Vitoria-Gasteiz, both in Bizkaia and in Gipuzkoa, among the soldiers. "He beat young people, between the ages of 15 and 34, and more men died than women, many men of 21 years. Recruits or seminarians."

As in all of Europe, in Vitoria-Gasteiz the pandemic caused few deaths among the city's children and those over the age of 45, "perhaps due to the immunization of previous influenza epidemics."

Álava, in an epidemic situation

On October 12, 1918, the National Health Council of the Civil Government declared the state of the epidemic in Álava "to combat the flu epidemic in most of the country's villages and in the capital." The newspaper Heraldo Alavés picked up the news and on 14 October he published a document detailing the measures to be taken.

The confinement was not ordered, but several decisions were taken to curb the cultural, social and economic activity of the country. Among them, the railway companies were asked to prepare a "gas disinfection chamber" and another place to "inspect and disinfect travellers". Likewise, the people's traffic was forbidden to "collect waste in the garbage warehouses of the city hall" and municipal police were ordered to clean every day "the spaces between the blocks of the houses of the old town".

On the other hand, on the doors of the churches "glazed or glass sheets will be placed at the height necessary so that people do not leave the dirt of their hands at the edges of the doors". In addition, the following document was sent to the church porch: "Please respect the temple and don't spit on the ground for hygiene reasons."

The City of Vitoria-Gasteiz was criticized by sectors such as the "lack of foresight" in the face of the flu epidemic and had to make decisions additional to those adopted by the Health Commission over the years. Thus, the dances of Plaza Nueva were suspended, rags shops closed and all kinds of shows were banned. Therefore, the theater and the pediment itself were also closed.

In the health crisis of a hundred years ago, there were also those who wanted to bring economic revenue to the needs of the population. Thus, the City Council and the Council launched special campaigns against those involved in the resale of lemons, fines for dairy farmers who increased the price of milk, sanctions against citizens who were collecting potatoes and confiscation of food.

On October 26, 1918, Heraldo Alavés collected it as follows: "Today the potatoes that the City Hall ordered last Thursday in the Casco Viejo have been put on sale. However, the mayor has known that there are vendors who have sent children and young people to buy these potatoes and is willing to punish these people with fines of between 50 and 100 pesetas."

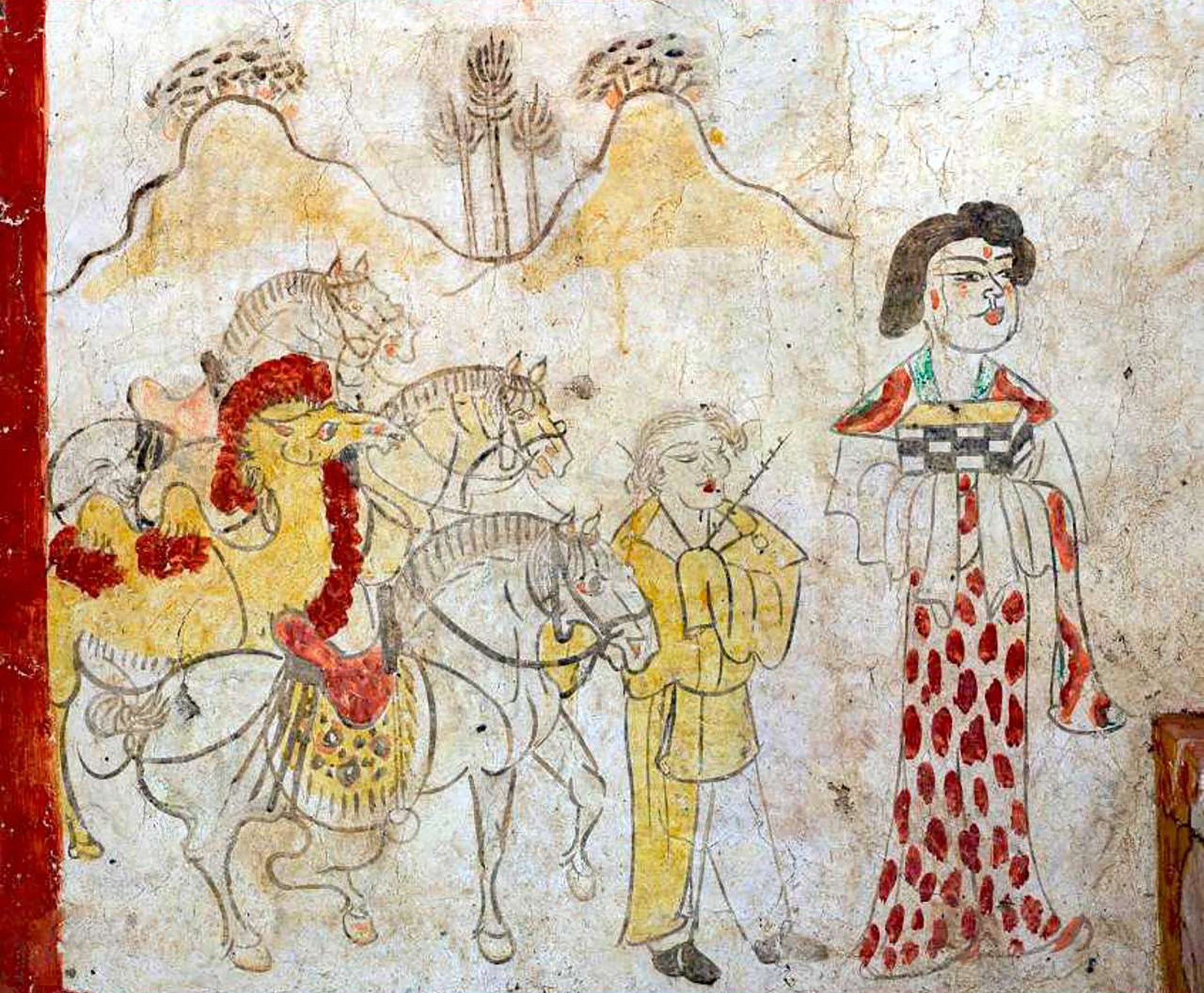

In the Chinese province of Shanxi, in a tomb of the Tang dynasty, paintings depicting scenes from the daily lives of the dead are found. In one of these scenes a blonde man appears. Looking at the color of the hair and the facial expression, archaeologists who have studied the... [+]

Carthage, from B.C. Around the 814. The Phoenicians founded a colony and the dominant civilization in the eastern Mediterranean spread to the west. Two and a half centuries later, with the decline of the Phoenician metropolis of Tyre, Carthage became independent and its... [+]

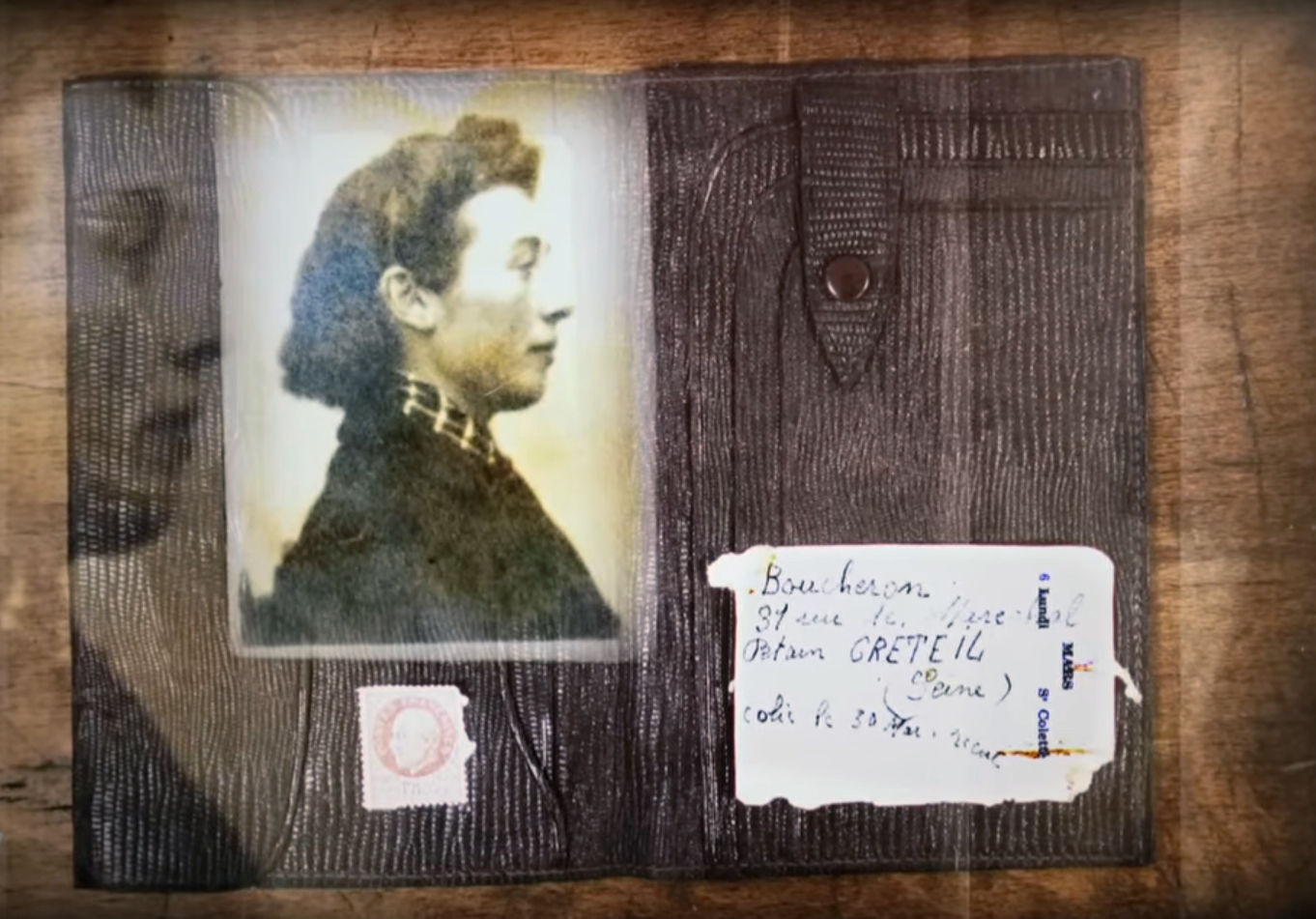

Salvador Puig Antich frankismoaren kontrako militantea izan zen. Askapen Mugimendu Iberikoko kidea, 1973ko irailaren 25ean atxilotu zuten. Gerra-kontseilua egin zioten, eta garrotez exekutatu zuten handik sei hilabetera, 1974ko martxoaren 2an. Aurtengo otsailean baliogabetu du... [+]

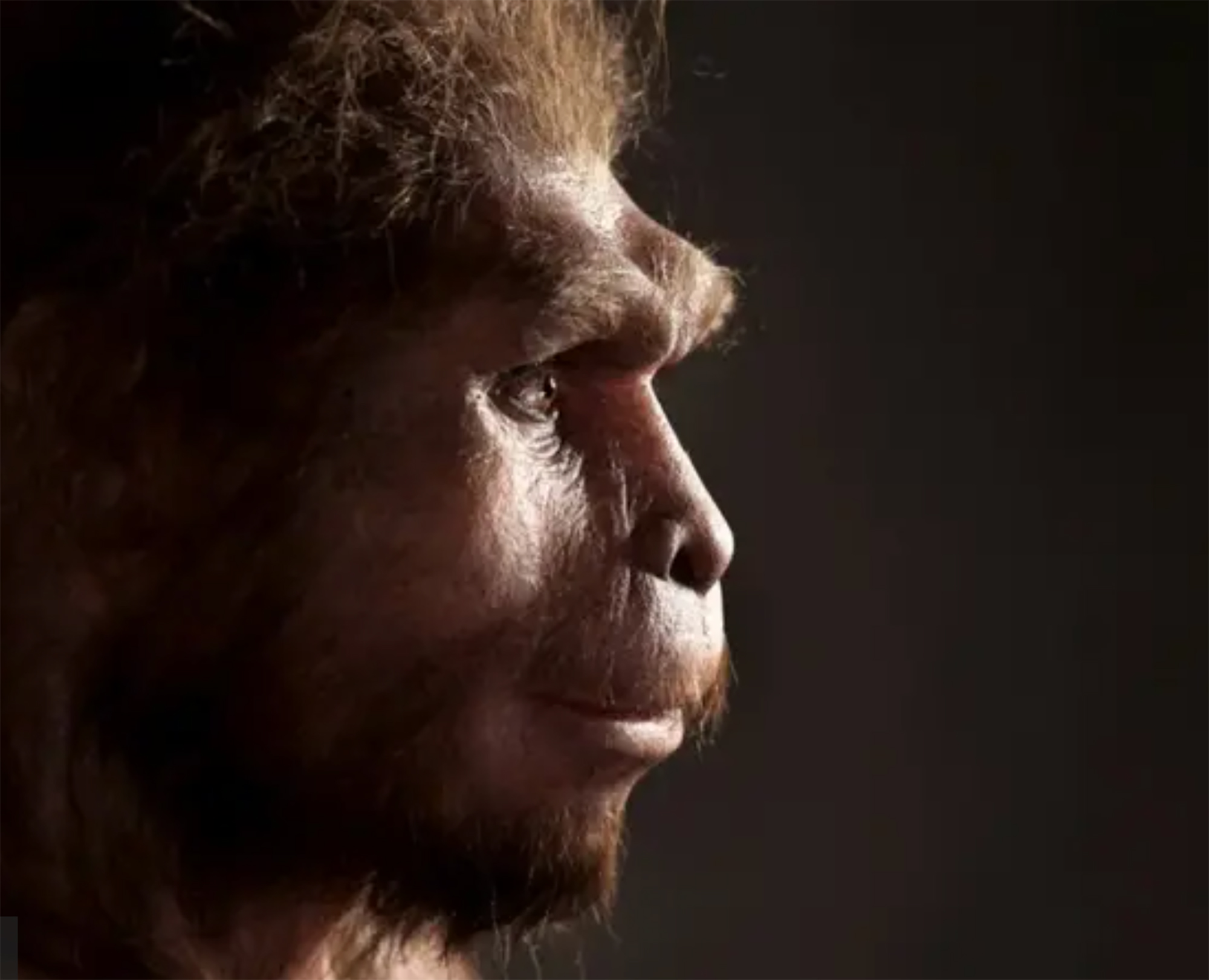

Rudolf Botha hizkuntzalari hegoafrikarrak hipotesi bat bota berri du Homo erectus-i buruz: espezieak ahozko komunikazio moduren bat garatu zuen duela milioi bat urte baino gehiago. Homo sapiens-a da, dakigunez, hitz egiteko gai den espezie bakarra eta, beraz, hortik... [+]

Böblingen, Holy Roman Empire, 12 May 1525. Georg Truchsess von Waldburg overthrew the Württemberg insurgent peasants. Three days later, on 15 May, Philip of Hesse and the Duke of Saxony joined forces to crush the Thuringian rebels in Frankenhausen, killing some 5,000 peasants... [+]

During the renovation of a sports field in the Simmering district of Vienna, a mass grave with 150 bodies was discovered in October 2024. They conclude that they were Roman legionnaires and A.D. They died around 100 years ago. Or rather, they were killed.

The bodies were buried... [+]

Washington, D.C., June 17, 1930. The U.S. Congress passed the Tariff Act. It is also known as the Smoot-Hawley Act because it was promoted by Senator Reed Smoot and Representative Willis Hawley.

The law raised import tax limits for about 900 products by 40% to 60% in order to... [+]