Burgos, 50 years ago

- 50 years of the Burgos Process. The Goldar Society organised a public colloquium in Eibar on 3 December. In addition, the association has made known the opinion of the then defense lawyers, Miguel Castells, Pedro Ibarra and Francisco Letamendia, who will participate in the concentration.

On 3 December it will be 50 years since the beginning of the Burgos Trial and we did the law. There, 16 political prisoners, accused of ETA militant or militant, were tried by a military court at the headquarters of the Burgos Military Government. Six of them were sentenced to death and subsequently replaced by 30 years in prison. The remaining defendants were sentenced to sentences ranging from 12 to 70 years ' imprisonment. One of the defendants was released, as he was already convicted of these events in the OPA section.

A war council consisted of five military and two alternates, all elected by the captain general of the Military Regiment. The Spanish Army had divided the State into military regions and the Captain General, the senior military head of each region, had the function of ‘Judicial Authority’, under whose powers was the approval or annulment of the ruling issued by the War Council.

The five soldiers of the War Council, without any knowledge of the Law, except one of the military, the so-called juridical-military — which knew a little about the military laws — all under strict military discipline and obedience, judged and punished the ‘civilian subjects’ who opposed the Franco regime, since at that time there were no ‘citizens’. These soldiers were part of the regime and its defenders.

As for military law and military law, an expert jurist in the matter said, at that time and rightly, that military law is for the law to put a military music group in the Vienna Philharmonic. Well, neither did the War Council military need special knowledge of the law, because the military law and its application were very simple and firm. Any criticism and opposition to the regime was punishable; the most frequent one, between 8 and 20 years in prison; but it could be, and was on more than one occasion, the death penalty.

On the scale of penalties, the offence that received the lightest penalty, although they could also be punished with death, was a crime of ‘military rebellion’, which included, inter alia, the following acts: Disseminate the news ‘in the same spirit of contempt of the State, its institutions, the Government, the Army or the Authorities’ and ‘hold meetings, conferences and demonstrations for the same purpose’, as well as ‘engage in strikes and similar events for political purposes or with serious disturbances of public order’.

On the other hand, the procedure for the War Council ' s judgment was very inadequate. The judgments consisted of very simple copies of the reports issued by the Civil Guard or by the Politico-Social Police Brigade (terrible BPS) on what the defendants did or said. Rather, it was the Civil or Political-Social Guard who decided what the defendants have said or done. It was Francoist justice.

As for military law and military law, an expert jurist in the matter said, at that time and rightly, that military law is for the law to put a military music group in the Vienna Philharmonic.

We have already said and written:

The Burgos War Council was a political judgment that was handed down outside the court of justice, with the mobilization of supporters and detractors of what was being played in the trial. The meetings of the Council coincided with the internal and external conflict, with the same internal and external conflict of content. The defendants assaulted and defended themselves at gunpoint in the local courtroom. And the reasons and behaviors given by the judges and defendants are the same ones that were given and taken abroad. Strictly political.

The Burgos War Council took on a very peculiar aspect. All classical defense techniques were abandoned. The system adopted was positive for defence. The Burgos process was a break with the intervention of the people. Or, to put it more nuanced, with the intervention of the peoples.

The mission of the defense lawyers was not to plug the raw political confrontation with a cloud of smoke. Thus, the lawyers, at all times coordinated with the defenders, did not cover in the governing council the strategies and political speeches of their defenders. His interventions did not hinder the process, but placed it in its true natural context, abandoning the law of confrontation of the political forces that conditioned it. It is very important to remember the popular mobilisation and, of course, the political mobilisation for the accused in this political confrontation. Strikes and demonstrations in the Basque Country and throughout the Spanish State. Not only lawyers, intellectuals and students... In Euskadi, all the Basque people and, above all, the working class, went to the general strike of the CAV. Both faced the Armed Police and the Civil Guard. Roberto Pérez Jauregi was killed in Eibar.

The defendants' statements decided to take advantage of the trial to make a political demonstration of their ideology and to denounce the regime, the responses of the prisoners in the interrogation phase provide a fairly broad picture of both the objectives and political thinking of their actions and the political, dramatic, economic and social situation of the Basque Country. Including the 'duty' (sic) to kill Meliton Manzanas, Chief Commissioner of the Political and Social Brigade of Gipuzkoa. Most of the defendants acknowledged their membership of ETA by specifying their position and, except for two militants, their functions and activities. The six accused of killing Manzanas denied what they were accused of, although, like others, they showed their support for this fact. And all of them stated that their objective was the national and social liberation of the Basque Country.

In this room, refurbished as a courtroom by the military government, the sixteen defendants of ETA became accusers of the Spanish fascist state. And fulfilling the purpose of using that interrogation for ideological vindication and for denunciation, the judgment, the impossible, was broken. The defendants were violently expelled from the room. The press and the public ventured. The military that formed the judicial apparatus and the defense lawyers were left alone. By then, however, the ETA defendants had already banned the prosecution’s lawyers from exercising their defence. And the lawyers fulfilled the will of the defendants.

The moments of greatest tension followed, in chronological order, as follows: on the one hand, the statements of the prisoners in their interrogations; on the other hand, the total breakdown of the trial, when the last prisoners finished questioning and yelled at the War Council GORA EUSKADI ASKATUTA and at the end all the prisoners sang by Eusko Gudariak; and, on the other, The contents of these three moments coincide with that of the unit that shows what the trial was for the political prisoners accused.

The Burgos trial became a general call against Franco. The fact that the defendants became symbols of anti-Francoism provoked great solidarity in the Spanish State and even in the world; in Euskal Herria, clandestine society won the street and openly confronted the forces of the Francoist order.

The Burgos process opened up a new scenario and, at the same time, a new process of confrontation against the regime. In this regard, we can only recall the doubts and weakness of the Franco regime with the strength and conviction that the Burgans have demonstrated in defending themselves and, above all, with the fronts of mobilisation in favour of them (including Europe and the American countries), which has given rise to the hope — and in many sectors the security — that the Franco regime was vulnerable and despicable.

In the Burgos Process, the lives of six people were barely recovered, thanks only to that great popular movement. We would like to underline this last paragraph, for current generations should never forget that 50-year lesson.

A ferocious Spanish nationalism appeared in the Plaza del Este in tribute to Franco; to the figure of the ‘internal enemy’ of Franco, which was made up of communism and working-class organizations, years earlier another force, ever stronger, had been added the ‘terrorist and communist separatism’, which eventually constituted an extreme anti-Francoist opposition in all the territories of the State.

Thus, the Army and the Police, who had quite a few difficulties with this widespread opposition, which had even received indications from the armed opposition ‘in the North’, did not obstruct it when part of the democratic opposition and one of the sectors of the regime began to jointly prepare the handover of the dictatorship to, at that time, transfer it to parliamentary democracy. The Burgos trial, therefore, was a general session of the alternative to Franco.

On the other hand, ETA de Burgos appears as a reference organization at the meeting point of all groups, organizations and movements opposed to the regime. Among other things, in this increasingly strong and growing labour movement. Moreover, ETA acted as a catalyst in this process of confrontation unity. Not formal but real. When Burgos happened, it seemed logical to think that a historical collective subject was being built in society. The people were achieving hegemony in the area of conflict and the right to national sovereignty of Euskal Herria was also being asserted.

The Burgos trial is remembered for many of the acts of the trial and, above all, for the social and political consequences it had. It is also important to remember what justice was in that political regime. We have already described the arguments, procedures and guarantees used by a military judicial process. It recalls that in those years, any political demonstration against the regime was directed at military jurisdiction. Let us remember the arbitrariness in the formation of a judicial system and the full submission to the repressive policies of the regime against the opposition. This allows us to compare it with the current judicial system. No doubt, different. Today, there are processes, supposed evidence, decisions, judges, courts, police actions and incarcerations that remind us of the cursed time and that we would all like us to say honestly and with conviction that it had happened.

We cannot remain silent, however, in view of the paradox, on the one hand, that the Spanish Government itself, late, very late, has proposed a Law of Historical Memory (in the end! ). IN THE CHAIR: MR ANASTASSOPOULOS Vice-President How can the criminal sentences in Burgos which would have been condemned if they had been carried out be put to life? How will we give back life to the five shot in 1975, Txiki, Otaegi, Baena, Sánchez Bravo and García Sanz? What about those thousands of deaths in 1936? The amnesia of justice takes signs of criminality if action is not taken immediately and forcefully, as it should have started in 1977, calling for the breakdown of the Franco system, rather than making transitional arrangements and arrangements. The lives of so many victims can no longer be recovered. We can only proclaim their struggle and give them the dignity that they legally deserve.

In the Burgos Process, the lives of six people were barely recovered, thanks only to that great popular movement. We would like to underline this last paragraph, for current generations should never forget that lesson of 50 years.

[Warning: The original version of the article is in Spanish and has been translated into Basque by Berria]

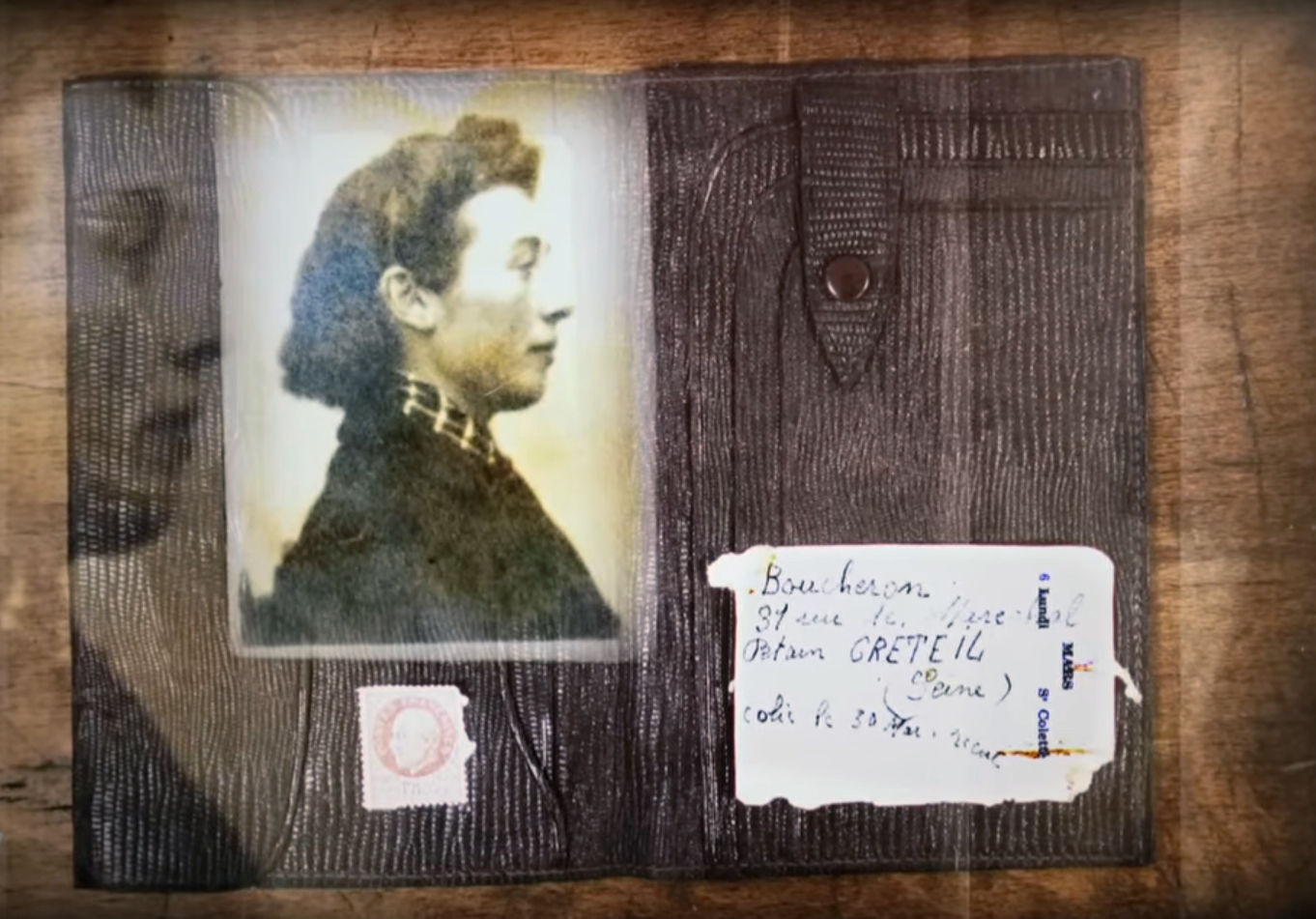

Oraindik ikusgai dago Donostiako San Telmo museoan Memoriaren Basoak erakusketa, maiatzaren 11ra arte. Totalitarismoek gizartea kontrolpean hartzeko erabiltzen dituzten metodo eta tekniken inguruko hausnarketa bat da, espresio artistiko ugariren bidez ondua.

Kirola eta oroimena uztartuko dituzte, bigarrenez, mendi-martxa baten bitartez. Ez da lehiakorra izanen, helburua beste bat delako. La Fuga izeneko mendi martxak 1938ko sarraskia gogorarazi nahi du. Ezkabako gotorlekuan hasi eta Urepelen amaituko da. Maiatzaren 17an eginen dute.

Fusilamenduak, elektrodoak eta poltsa, hobi komunak, kolpismoa, jazarpena, drogak, Galindo, umiliazioak, gerra zikina, Intxaurrondo, narkotrafikoa, estoldak, hizkuntza inposaketa, Altsasu, inpunitatea… Guardia Zibilaren lorratza iluna da Euskal Herrian, baita Espainiako... [+]

Gogora Institutuak 1936ko Gerrako biktimen inguruan egindako txostenean "erreketeak, falangistak, Kondor Legioko hegazkinlari alemaniar naziak eta faxista italiarrak" ageri direla salatu du Intxorta 1937 elkarteak, eta izen horiek kentzeko eskatu du. Maria Jesus San Jose... [+]

Familiak eskatu bezala, aurten Angel oroitzeko ekitaldia lore-eskaintza txiki bat izan da, Martin Azpilikueta kalean oroitarazten duen plakaren ondoan. 21 urte geroago, Angel jada biktima-estatus ofizialarekin gogoratzen dute.

Bilbo Hari Gorria dinamikarekin ekarriko ditu gurera azken 150 urteetako Bilboko efemerideak Etxebarrieta Memoria Elkarteak. Iker Egiraun kideak xehetasunak eskaini dizkigu.

33/2013 Foru Legeari Xedapen gehigarri bat gehitu zaio datozen aldaketak gauzatu ahal izateko, eta horren bidez ahalbidetzen da “erregimen frankistaren garaipenaren gorespenezkoak gertatzen diren zati sinbolikoak erretiratzea eta kupularen barnealdeko margolanak... [+]

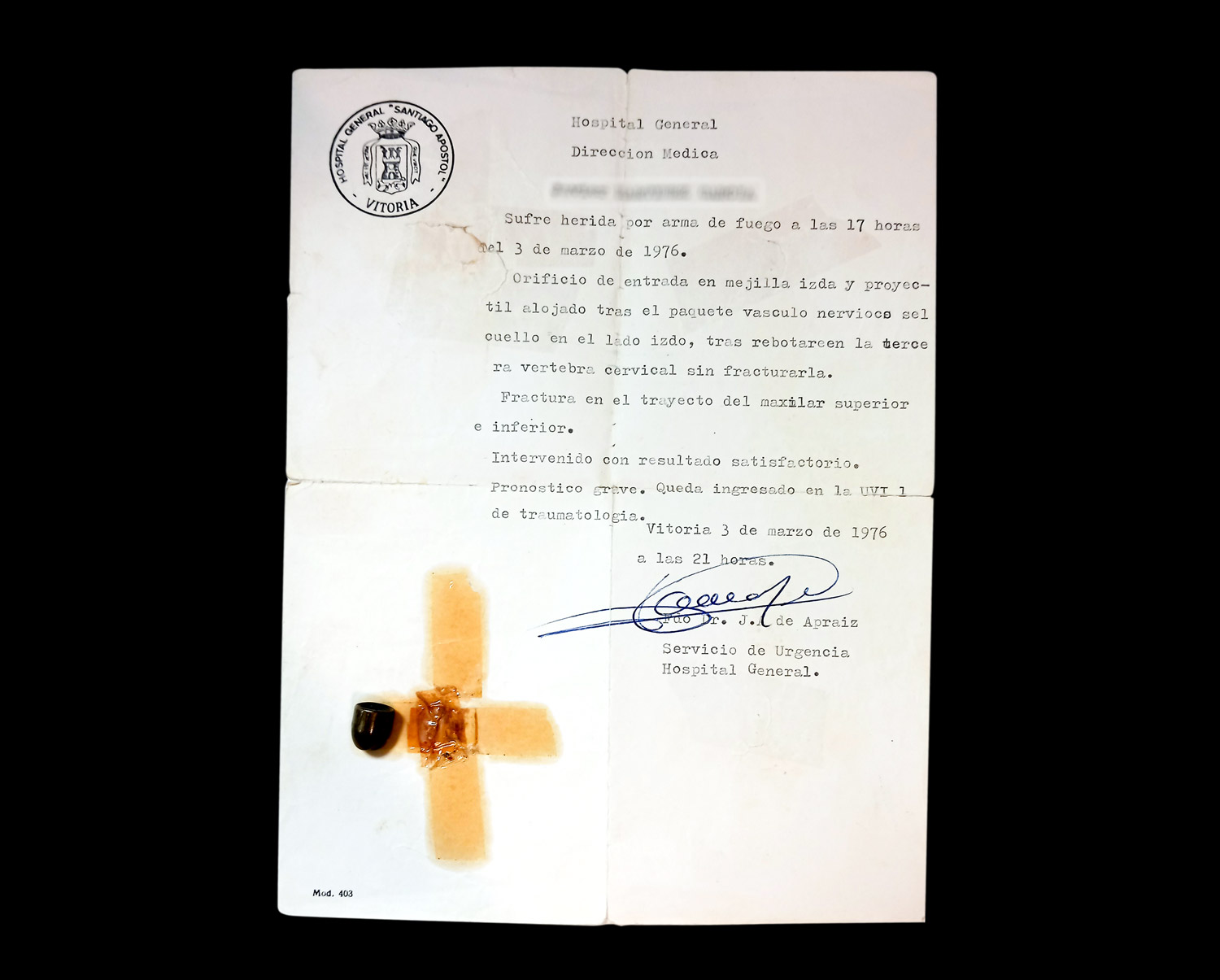

1976ko martxoaren 3an, Gasteizen, Poliziak ehunka tiro egin zituen asanbladan bildutako jendetzaren aurka, zabalduz eta erradikalizatuz zihoan greba mugimendua odoletan ito nahian. Bost langile hil zituzten, baina “egun hartan hildakoak gehiago ez izatea ia miraria... [+]

Memoria eta Bizikidetzako, Kanpo Ekintzako eta Euskarako Departamentuko Memoriaren Nafarroako Institutuak "Maistrak eta maisu errepresaliatuak Nafarroan (1936-1976)" hezkuntza-webgunea aurkeztu du.