Asier González: "The last 40 years have been years of struggle for justice"

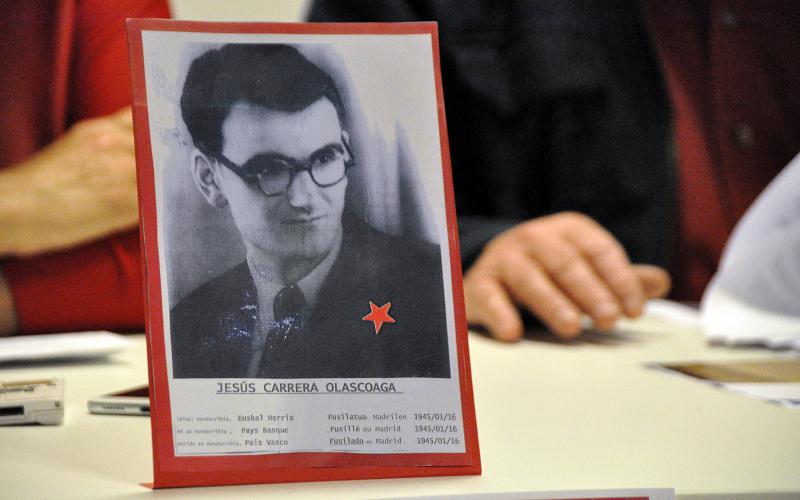

- It has been 40 years since Yolanda González, a young woman from Deusto, was murdered in Madrid by an extreme right-wing group headed by Emilio Hellin. The attack on the mural of Yolanda in the Bank of Deusto has not blurred the acts of remembrance and claim. Around the anniversary we have been with Asier González, Yolanda's brother, talking about the current state of his figure.

Soon after painting they attacked the new mural reminiscent of your sister Yolanda. How would you define what happened?

The attack has been perpetrated by a group of people of fascist ideology, as reported by the Basque Department of the Interior. I would call intolerance an act. The ideology behind me doesn't matter. I don't care whether it comes from the extreme right or from another ideology. In short, it has been an act of intolerance. Nothing is lawful. An aggression by the memory of a victim is very serious. In fact, the actions and the means of memory are very important not to repeat what happened, to remind everyone, also young people, to know what happened.

How have you felt and how has the family felt about aggression?

In recent years there have been several attacks on a plaza named Yoldanda in Madrid. In a way, we're used to that. We are prepared, even if we suffer from what has happened. But when it happened for the first time in the Deusto Bank, I have to confess that I felt a shiver. I was surprised. Then, seeing people's response, my pain completely dissipated.

How can we react to this type of aggression?

Forcefully, even though the word itself is a little ambiguous. How can we express that firmness? There are several ways. Outside the institutional sphere, I think it is great to deal with the Ribera’s neighbours in a concentration. Others have decided on their own initiative to cover it with white paint. Any initiative to respond to aggression is to deal with insult. On the other hand, if an answer comes from the institutional sphere, then well. The institutions must have a clear position when the memory of the victims is attacked, so that the response is not always in the hands of the resident initiative.

How has the City of Bilbao responded?

Several representatives of the City Hall have shown interest in this initiative. We have been told, and I found it a great idea that they will prepare the Yolanda mural model so that, if something similar ever happens, it will answer and reproduce quickly. This is a good example. The institutional scope in this case has surprised me for the good, as the mural was not created at all on the initiative of the City Council.

Yolanda was killed 40 years ago. When did he reawaken his interest?

We began to see a radical change in 2013, when the newspaper El País published information about the hidden life of Yolanda's killer. It had a huge impact on the media and on society. Some felt the need to defend their memory and the media the need to recover the case. Yolanda's presence also implies being present for those who undertake vandal initiatives.

Has media pressure helped you?

Yes, it has helped us from time to time, no doubt. For example, the delivery order of Emilio Hellín was approved by the Spanish Government because of media pressure. And in 2013, the same thing happened. The Government was under media pressure on the playing field. He was forced to respond, and the brothers summoned us to the meeting. But a few months later, Yolanda's case lost all of its attention.

Has your family achieved justice and truth?

I often think about people who don't know anything about what happened to their family members. I am aware that there are far more dramatic cases than ours. In our case, Yolanda's material killers had a trial and ended up in jail, although they failed to serve their full sentence. As for the intellectual authors, the research reached a certain level, with some members of the New Force. We therefore have a truth about what has happened. But we know very well that we don't know the whole truth. Emilio Hellín explained on several occasions that he would not report all the people behind him. But we have not been able to go further.

What institutional support have you received?

The Spanish Government has done nothing to respond to the demand for family justice and truth. It has not taken any steps on its own initiative. Our struggle has always been against the institutions, to demand justice. At the level of the Basque Country, progress has been made in the area of justice, truth and reparation. In this respect, Spain is a long way away.

Did you feel like second-rate victims?

Yes, especially parents. When in 1987 Emilio Hellín left Paraguay with a prison permit, his parents moved to Valladolid to file a complaint. They had a very bad time, so she explained it to me. They were made to feel secondary victims, and more than that, as if they were criminals.

Has the repair come to your parents?

They came late. Most of the reparation initiatives started starting in 2015, and my mother had not realized the reality anymore. So, not for parents, yes for other siblings, yes for siblings.

Has it felt pressure from politicians?

We have never been involved with victim associations or political groups. That is why no one has used us. They've approached me by inviting me into some group, but I haven't. We've had the door closed, because if you go into that game, you can use it.

“Yolanda’s struggle is still alive,” said those who met him. What do you notice?

The reasons for their struggle, 40 years later, are among us: feminism, class struggle or what is now called social struggle, independence -- these are challenges that are still alive. And of course, the fight against fascism today, here and in other territories, is very much alive. More than ever, even if it seems strange. Those who think so in the Spanish Parliament have an enormous representation, more than when they murdered Yolanda.

Does time heal wounds?

We have not had hatred at home, and that has been thanks to the education our parents have given us. Our mother has educated us in families free of violence and we have not had that feeling. A feeling of injustice and impotence yes, but not hatred.

What does Emilio Hellin feel like?

It makes me nauseous, but not only because I'm a killer, but because I'm a character that it is. He has never regretted it. He says he did what he had to do. Anti-democrat is, in principle, a murderer and a terrorist.

How do you remember your sister Yolanda?

I was six years old when he was killed. I remember that the person was very active, dynamic, always coming in and out of the house. Talking on the phone, about their meetings… At the age of sixteen no one else had the responsibility and attitude. At home we didn't have a political environment, so his curiosity woke up out of the house. Their maturity and their safety were amazing.

The murder of Yolanda is one of the cruellest crimes of the Transition. How do you want others to remind Yolanda?

As is the case lately. The initiatives of recognition and affection that have emerged in his honor are incredible, transcending those expected. They're pretty. It is a gesture of generosity, of the people, to go out into the street with many problems and claim the figure of Yolanda. I'm amazed at all of this.

How would you summarize the last 40 years?

It's been years of struggle, of struggle for justice. This has been our constant work for 40 years.

“In the Ribera it is very present”

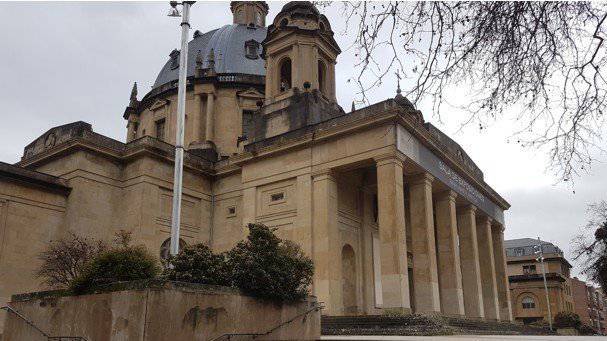

Putting the name of Yolanda González to the plazoleta of the Ribera, what was it for you?

It was very special. We were in the plenary when the initiative was adopted. I have a very nice memory.

Do you realize that Deusto Yolanda González has become a symbol?

Yes, in the Deusto Bank it is very present. It's impossible to think otherwise. It's very important for the neighbors. I am very sorry.

Tafallan, nekazal giroko etxe batean sortu zen 1951. urtean. “Neolitikoan bezala bizi ginen, animaliez eta soroez inguratuta”. Nerabe zelarik, 'Luzuriaga’ lantegian hasi zen lanean. Bertan, hogei urtez aritu zen. Lantegian ekintzaile sindikala izan zen;... [+]

Eraispenaren aldeko elkarteek manifestazioa antolatu dute larunbatean Iruñean. Irrintzi Plazan manifestazioaren deitzailea den Koldo Amatriarekin hitz egin dugu.