Mom, I want to be an artist.

- We hope that this article serves to rise to a stage or stage or to give a small idea of the reality of those of us who stand in front of the cameras.

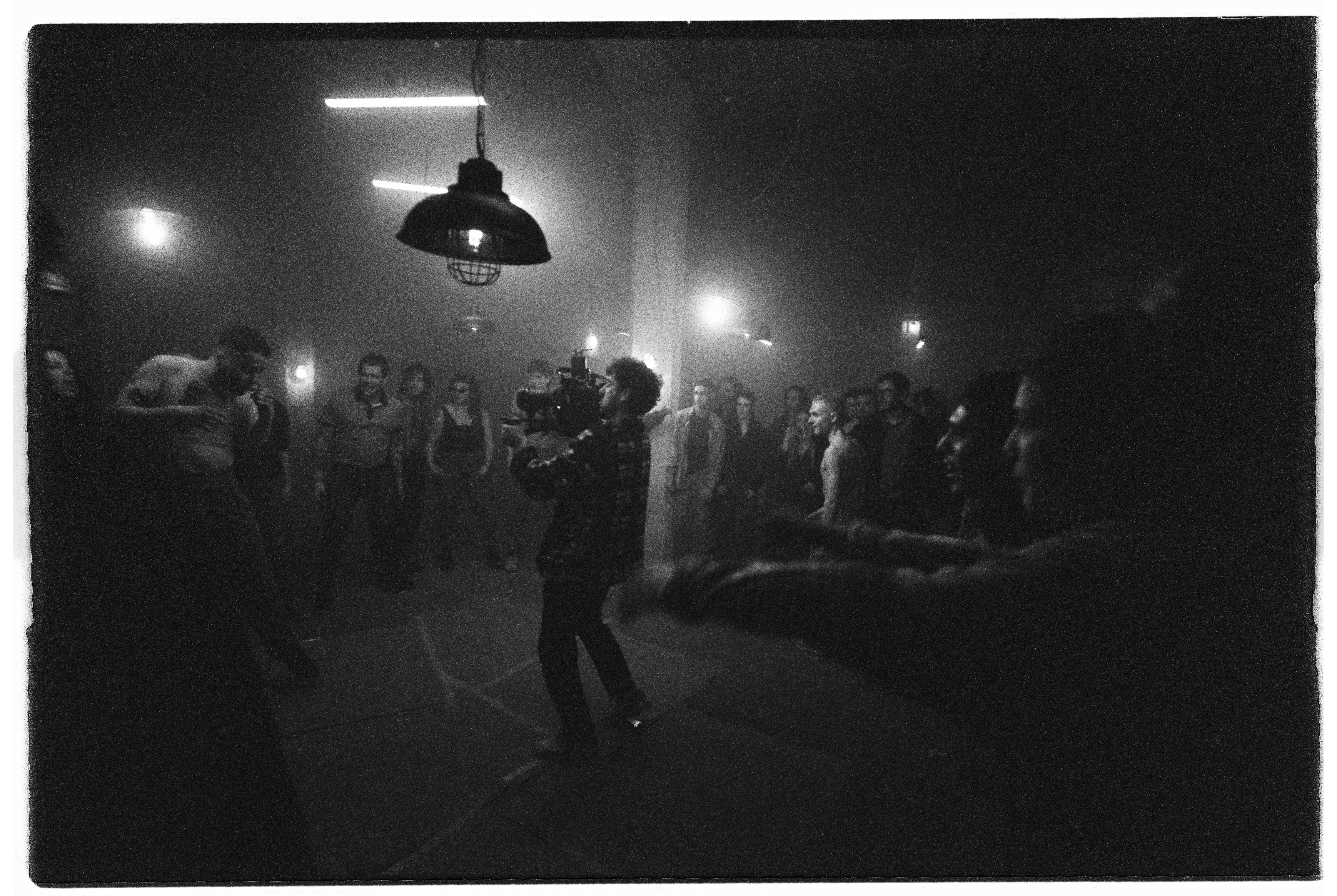

Juan, priest; Miguel, accountant; Julia, nurse; Andrés, physician; Natalia, economist; Pedro, financial consultant; Marta, waitress; Alfredo, store dependent... Many names and professions, which have something in common: they are figurative in audiovisual media. Following the 2007 crisis, many observed that their jobs were crumbling and that their working conditions were disappearing, that these working conditions would never return. Most started working in the sector because of the need to make extra money with a day job, and in that work they have ended, which tends to be more than a full day, but which is not taken into account: the time spent in the search for stealing, the castings, call this agency, now another, and so, with a little luck, you get to work one or two days this week…

It seems surprising that in the audiovisual sector, which is growing and which has very good opportunities from the point of view of industry, as employers say, job insecurity is so great, but if we look at the performing arts, the situation does not change very much. Temporary work, usually one day, such as figurants or actors in short papers, and the mantra “cannot be repeated” that the producers overuse. To give an example: a figurative companion is going to work on a television series and his job is to walk on the sidewalk opposite to the place that the actors use on the scene. It is impossible for the spectator to look at it, even more so when the background appears unfocused on the plane. However, it may be the only day working in this series, as the agency has to attract people to “sell it in bulk” continuously. Thus, the professional figure, which had the possibility of taking a (insufficient) day, sees its situation increasingly weaker: the experience in this work does not provide greater stability, but quite the contrary.

“Having experience in professional figuration does not imply greater stability, but quite the opposite”

In September 2016, the AISGE Foundation published a final report on the socio-occupational situation of the actors and dancers sector in Spain, which reflected rather disappointing data. Based on the 3,282 surveys, only 43% of the professionals who participated in the study worked in the art sector in 2015, compared to 66% in 2004 and 63% in 2011. In addition to the endemic unemployment of this profession, the wage situation is very worrying: if we look at the salaries of the year, the study indicated that 53% did not exceed 3,000€ per year and 29% received less than 600€ per year, while only 8.17% received more than 12,000€ per year, and 2.15% received 30,000 or more per year. The evolution of these historical data is very worrying, as the number of workers with the highest precariousness has multiplied. These data show that the number of workers who pay below EUR 600 has doubled.

But this data doesn't show all the work you need to do to prepare a function or shoot, or the time you need to do it. Nobody tells the profession’s “out-of-employment” dedication. To data on the precariousness and shortage of wage work – 46% of the actors worked less than 30 days in 2015 – we must add the effort in training and professional training that requires being prepared to defend themselves in a casting that allows to obtain paper. That requires hours and money. In addition, if we add that 11.7% of the work obtained is uncontracted, we need to make a serious and in-depth reflection on what is happening in the sector.

Obviously, the gender gap is present: the unemployment rate of women is 6 points higher than that of men, prevail in the group of people with incomes below 600 euros per year and are the majority among those who work without a contract.

“Gender gap: Women’s unemployment rate is 6 points higher than men’s and they are also the majority among those working without a contract”

The arrival of Netflix, Amazon, HBO and many other big digital and production platforms in the audiovisual sector of the Kingdom of Spain seems to be going to bring a lot of work, or at least that's what's happening again. Does that bring better conditions? From the CNT’s Film and Performing Arts Coordinator we have dealt with different threads on the pretext that these are low-budget productions for digital platforms (RTVE, Movistar+ and other large communication groups, for example) that offer inferior conditions to collective agreements or that directly request figures and actors for free and without contract. Fortunately, our implementation in the sector is profound and there are some examples of the expansion of our capacities: for example, the colleagues of the CNT union of Teruel, after receiving a simple warning call, found a shoot in this province in precarious working conditions. From the organisation, it is possible at least to cope with these situations and improve our working conditions.

Looking at the salary levels in the audiovisual figuration, compared to the average working, it is clear that the accounts do not leave. A day of 8 hours is €45.5 gross and with a little luck it can be done two days a week. As a result, those who work in figuration receive an average of € 370 per month. Therefore, they also have to work on other works similar to precarious ones, such as event hostesses, small hospitality factories on weekends, or, in some cases, alternative theatre performances or microtheaters that allow them to combine both things.

In addition, this type of work brings together people with very different mentalities about employment, even antagonistic, which allows us to observe those who have a high degree of professionalization in the figuration and, along with them, those who dedicate themselves sporadically, who do not question unpaid jogging or works that do not comply with the law, since they do not understand these works as employment. This affects the conditions of the whole sector. In addition to all this, there are major differences between the different territories of the State: for example, it is clear that fraudulent practices are much more obvious in the area of Andalusia, where the problem is very serious.

Another reality resulting from this heterogeneity of figurative workers is the complexity of trade union activity in a sector with such a disparity in employment. It is easier to work synonymously in series or films in which rodajes have a journey of months than in advertising, where in a couple of days the production ends. That is why the situation in Madrid (where most of the production of fiction is concentrated) and that in Barcelona are very different, where mainly advertising is recorded. On the other hand, the inverse correlation between precariousness and unionisation is evident, as when dealing with abuses, working conditions are improved.

We have mentioned micro-theatre, which can serve as the last example of how you exploit yourself. Imagine a small format room, with a maximum of 20 spectators, two stage actors, four performances in a row, 5€ per entrance, which receives 50% of the room. Consider the time it takes to create the work, to rehearse, to acquire the room, in what costs the props, in many cases the worker is left without a contract or as a false self-employed … In this case, we are talking about EUR 100 gross per actor a week: if we take into account all that preparation time, it is clear that they work to be poor.

We hope that this article serves to rise to a stage or stage or to give a small idea of the reality of those of us who stand in front of the cameras.