Joan Tartas (Sohüta, 1610 - date of unknown death) is not one of the most famous writers in the history of our letters and yet we discover good things in this “mendre piece” whose title, let us admit it from the beginning, is probably not the most commercial of the titles that have been placed in this world. Neither will his subject overwhelm us with joy and joy – for Tartas, after all, spends the whole book reminding us that we will die, and acting according to that thought, and not otherwise, that we will be saved. On the other hand, compared to Axular, the writing of Tarts is not so bright. But the medal we have comes back to the other side. We express that the way to kill Ontsa (1666) is a book that we must honor, and that tells us firmly: antecedent of many current trends, sometimes fantastic, sometimes philosophical-existentialist, full of stories that are read with delight, a box of surprises scrapped under a debot book.

Let us speak, first of all, of the author Tartas, of his modern subjectivity, which we find clear and palpably in the numerous doubts he manifests in this book, and which makes his perplexity be like that of the neurotic writers of three and a half centuries ago. “My tribaillu aphüra meriting to teach you phena,” sometimes we see ourselves on the verge of suicide, sometimes we see ourselves –….to every symplailmündü that I am a good man-bird, sometimes a poor ill aphez and sometimes a joke to the guitar.

The priest of Arüe therefore ended this work with the dismissal of these auto-boicots. It started again with a dream. “In the opening and closing of my eyes, while I was telling myself that in the shadow of an outburst, I went to mine, slept, I made a great dream and a mystery, it seemed that in my dream, in my dream, there was a tropel of men and women, who went up to heaven, and therefore were forced to come down. Well, yes, an apocalyptic dream. But a dream, after all.

Neurosis, the end of the world. We have to lift a bit of the mood. Take into account the wording of the book we have. The insightful reader, seeing the punctuality of the quotation from the previous paragraph, would notice another particularity of Tartas, how it is that phrases such as the sequences of film planes are written one after another, so that if a phrase from Ontsa on the road of death begins to say “my friend”, it must be ready, and because the chain of words begins to move as the Basque medium in the year 1970.

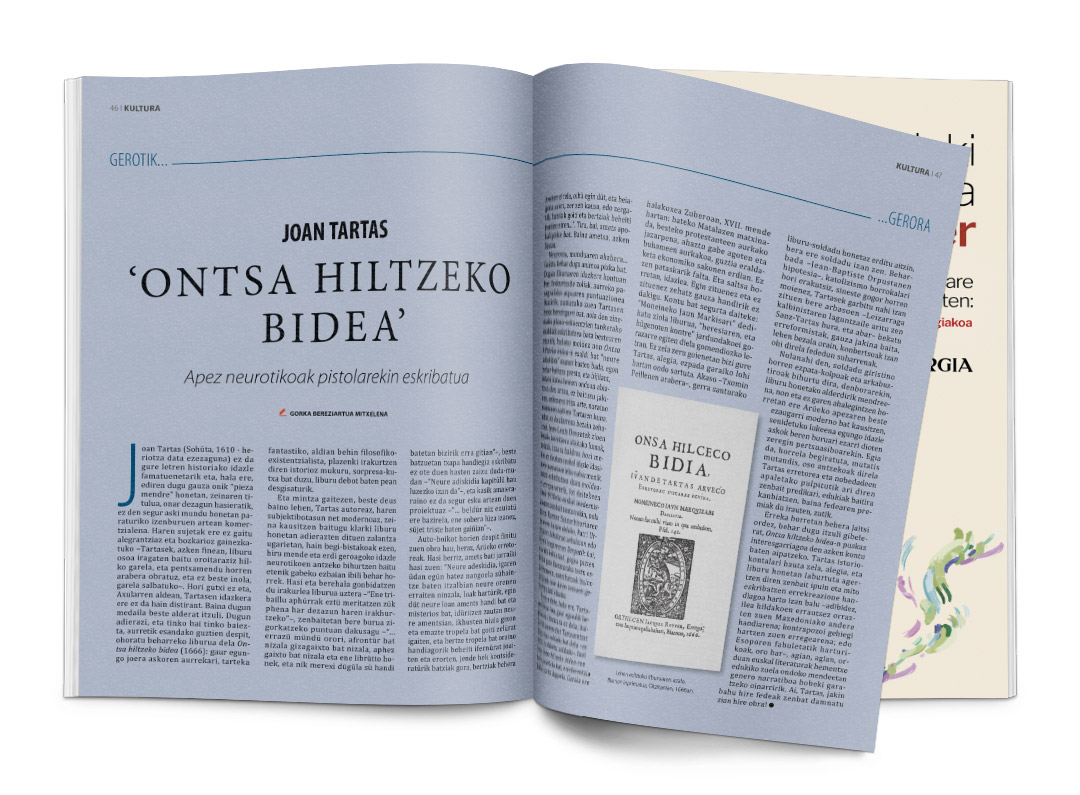

However, you will say that this book of Tartas, seen since today, is not literature; but I will tell you that for Tartas this book is a soldier – not a hammer, not an axe: a soldier – which is another thing of Ontsa hilbidea, which is full of war references. Such a time also in Zuberoa, in that 17th century: the rebellion of Matálaz, the persecution of Protestants, not to mention the burdens and the bohemians, all in the midst of profound economic transformations. There was no shortage of patinas. And in that mess, the writer. We don't know much about what he did or what he didn't realize. An account can be secured: He dedicated the book to “Mr. Marquis de Monein”, which in the letter of recommendation pays tribute to the “cons to heresy and to the hügenots”. That our Tartas did not live in the highest skies, that is, in that mud of the time. Perhaps – according to Txomin Peillen – before giving birth to this Holy War book soldier, he was also a soldier. Perhaps – the hypothesis of Jean-Baptiste Orpustan – demonstrating that fighting Catholicism, as it is known, Tartas wanted to clean up the reformist sins of his ancestors, Sanz Tartas, who worked as a collaborator of the Calvinist Leizarraga, etc., because, as you know, the most ferocious believers are the converts.

However, the swords of the sword and the gunfire of that Christian soldier have eventually become the most archaic aspect of this book, unless we try to find a new modern quality of the priest of Arüe that reconciled it with the persuasive task that many current writers have imposed on themselves. Certainly, if one considers, mutatis mutandis, the parish priest Tartas and some preachers who speak from the pulpit of the novelties are very similar to the others, since contents are exchanged, but the need for faith remains standing.

Instead of descending down that creek, we have to go back to refer to a more interesting question in Ontsa, the road of death. Tartas was a great storyteller, and if there had been a greater reaction to writing some of the stories and myths that are summarized in this book – for example, the great lady of Macedonia, who combed her hair with the ashes of the dead; that of the king, who took too many counter-apozones; or that of the fables of Esopo in general – then perhaps the Basque literature would have a genre in the next few centuries. Ah, Tartas, if you knew what your faith has repented of your work!