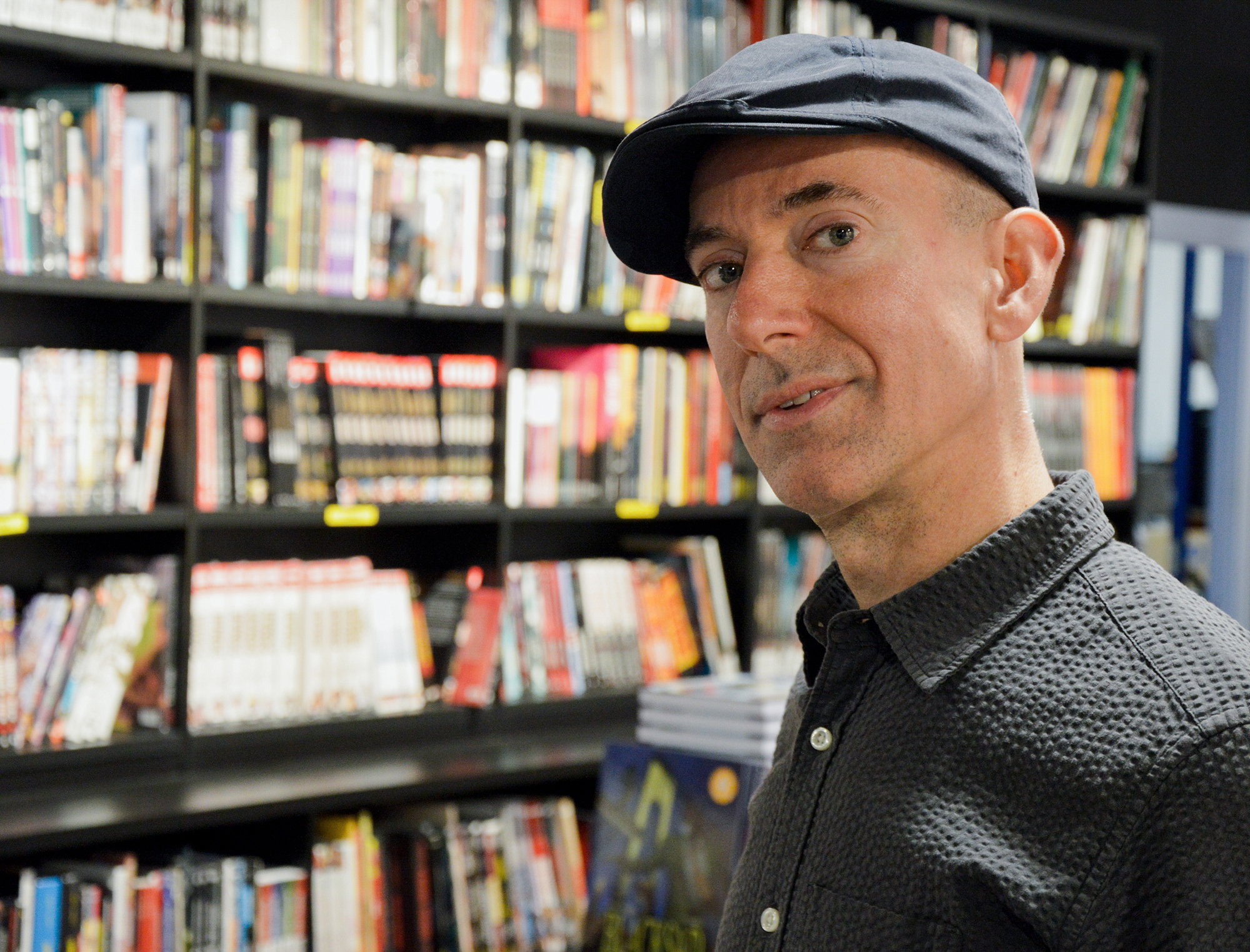

- American author of cult graphic novels, Craig Thompson, has visited Europe to present his latest work, Ginseng Roots (Astiberri, 2024). In Bilbao he has made two presentations and proved to be a friendly, close and fast artist – he has written in Basque “thank you” in all the comics he has signed. It has shown that it is also predisposed to discussion.

Your latest comic book, Ginseng Roots has a wide variety of ingredients: your family, Wisconsin, globalization… Actually,

it’s a story about ginsengari [Panax ginseng]. The plant is the core of the story. I spent my childhood on ginseng plantations, from 10 to 20. This herb is used in Chinese medicine, but when I was young, the world's largest production of American ginseng was made in my small rural village, lost in the middle of nowhere.

The comic book begins with a very hard component: the wage work of children. Did you want to take down the American dream?

For me, this is the peak of a middle-aged crisis, as far as my work activity is concerned. I've been drawing comics for 20 years. It has become commonplace to me and I often didn't enjoy it. I have fought with my work in recent years and it has helped me to return to the roots of the first place. I mean, how my work of ethics and the comics that I bought with that first money came about. Thanks to those comics, I became a cartoonist later. It led me to reflect on my work and my work on ethics, whether it's drawing agriculture or comics.

Ginsenga, middle age… That’s all in the comic book, but what you want to work on the bottom: How did the world shape you, or what form is the world taking?

That is a good question. Both. Ginsenga wasn't conscious in my head before this project. It's nothing that I've thought about for 30 years, but once the memories began to appear. So I started talking to my sister and my brother, and the memories were opened. That and researching the roots of the ginseng led me to immerse myself in a multitude of issues that interest me: globalization, wage labor for children, evolution of agriculture from small peasant families to the big monoculture corporations, connection between the military and the pharmaceutical industry… Suddenly, Moby Dick showed himself as the white bale, a way to address various issues.

It's true that all of this is in the comic book, but at the same time, it looks like you've made peace with your family and with Wisconsin and it's a confession of love. The Blankets comic was exactly the opposite.

Totally. I started Blankets at the age of 33. At the time, I was experiencing the trauma: childhood, the small oppressive people, the people who harassed me, the repressive religion of my parents and their authoritarian attitude. All of that was inside of me.

It's been 24 years. I'm an adult, and this work has smoothed my posture on all of the above, and especially looking at my parents. I have a closer relationship than ever with my parents and communication is alive. They're more vulnerable to age and they need my help.

In addition, the situation is fun, I know those hard and strong farmers who, now that I am an adult, seem to me to be generous people and I find it easy to talk to them. When I was a child, I wanted to flee the simple life of that place. Today, however, I will not say that I have nostalgia, but I do respect and admiration.

It tries to bring out some contradictions. For example, the people of Wisconsin, a Trump supporter, live in a very simple way, and compared to the lives of other Americans, it doesn't seem so capitalist.

Yes. In the book there's a component about Trump's election, and that led to collective trauma. I tried to understand it. In fact, when he was appointed president in 2016, I lived in Los Angeles and nobody thought it was going to happen. But when it happened, all the people looked at me for explanations, because I was a member of the white class community of rural workers in the interior of the United States. They seem to think about this. “Why has your people chosen Trump?” For many, Trump voters are violent white supremacists, but I knew it wasn't the case. I mean, a lot of people are friendly, reasonable and honored.

In any case, I did not want to reflect my political opinions in the story, I have tried to act as an author of documentaries and silence my voice, to listen to the personal aspects of the interviewed farmers and their families.

One of the issues that appear in the comic book is class oppression.

The truth is that my village, Marathon, of 1,200 inhabitants, was a rich place for the production of gin. Many of the peasants who sold it were millionaires. Despite being a rural community without education, people had money. But we don't. My family wasn't in that business. Marathon was a very special place and that made us poorer, because the children of the peasants had money.

That's why he never admitted you?

I was always a stranger. Partly because I was a thin boy, but it didn't help my family's religion. Because of these beliefs we lived outside the community, the parents did not allow me to relate to those outside our church. Isolation is the characteristic of a sect. So it was a confusion: my introverted character and the ban on being with other boys and girls, because they weren't from our church.

This ban was pushed to the extreme and forced you to leave school.

Yeah, it seems like you always thought about doing it. Apparently, they wanted to do a Christian home education, but they didn't know how to do it. When I only had one course left to finish high school, they decided that there was nothing more important than avoiding secular education, the theory of evolution, etc. If I had had more will, I would not have accepted it and at least I would have received that diploma, but it was very passive and I didn't care. In any case, having lived through religion in this way has led me to give up being a Christian, because for me it has been an oppressor.

You were accused of cultural appropriation with the Habibi comic book, and before you started this latest comic you valued that you didn't do it for that.

When I announced this comic book, in 2019, they filled the internet with protests in the United States. They didn't see the comic book, but they were upset by the same idea, they thought it would take ownership of culture. According to them, with Habibi I did it with Islamic culture and with China I would. In his opinion, I had no permission to do so, because I have

my cultura.En any case, this comic does not refer to Chinese culture. Despite everything, I received very big criticisms and put the comic book aside for six months. I didn't draw it, but during that time I realized that comic book was an unconscious answer to those criticisms, with one question. How does your culture overlap with others?

The ginseng produced in my small town was consumed throughout the Chinese market. For me, that had no value or meaning. As a child, it was a job for me, like any bad job, just a little bit of money. But I've fixed that now, asking what ginseng is, what it means in Chinese culture and medicine. Before I did this book, I didn't think I had a culture of my own, but this has helped me understand that my hometown is a very special place.

In the Basque Country he said that he has a hand sickness and that he has to spend money on treatments with the American health system. How do people get it from here? A

system that makes no sense to anyone, nor does it make sense to Americans. I'm a freelance worker, I don't have a regular job. In general, health insurance is paid by companies, not counting your salary, but I have to pay it on my own. $700 per month. That doesn't mean I don't pay when I go to the doctor, but I can visit him without paying up to 20,000 dollars. That's what insurance pays. In the meantime, they allocate our taxes to pay the military and not to the health or education system that we really need.

It's the most disappointing part of being American, and the situation, in my case, is a result of the nationalization of the Obama administration's health care system. Before that nationalization, freelance artists didn't need insurance, and it was much cheaper, about 300 dollars. The price doubled with the change.

There were probably many things hidden in Congress, to sabotage Democrats' efforts to approve the original proposal. In the end, the law was distorted and has become detrimental to all citizens. Living conditions are much worse in the last decade for the working class and the middle class, and that is madness and political disappointment. That is what we are living in the United States.

You've made a lot of gestures to pop culture: comics, toys -- is it your debt to your childhood?

Yes, this book is also an attempt to meet my love for comics, because it has become a job for me. I've made an effort to get inside that nine-year-old or ten-year-old, because then I fell in love with the comics: superheroes, young Ninja Dortoka… For me it was a time without malice, and it's not the comics I want to do now, but I was fascinated by the comics I wanted to find. A drawing friend says it's our job to understand every day how to keep love with comics. How to keep the passion of childhood alive.

On the other hand, Chua Vang and other migrants like Hmong appear in the comic book, who at the age of ten had to leave their childhood to become adults to whom they were pushed. They couldn't stay at home and watch the cartoons. That is how I have gone through the war and genocide of the people of Hmong, at the hand of the pop culture that we were consuming at that time.

Chua's father had to leave Laos because of the secret CIA wars during the Vietnam War. In any case, the only secrets of war we knew in childhood were from the Marvel Secret Wars saga. Chua's father was a child soldier, and with age we started buying the first comics.

"A friend who's a cartoonist says it's our job to understand everyday how to keep love with comics. How to Keep Childhood Passion Alive"

Can you survive by drawing comics?

Yes, I'm happy and I've survived because of her, sometimes just. I don't have any property, not even a small home. I live very humbly, but I'm still lucky. José Sacco, my friend and mentor, says: “In the United States, ten breeders may live from graphic novels.” And he and I are two of them.

Not many, most people have to do as a professor or design. Others have to draw mainstream comics, superheroes and more commercial comics. We can make personal and literary comics.

It's a sacrifice, but I accept it. Now I'm 49 years old and I've been able to do comics for 20 years, since I signed a contract to do Habibi. I then took a step forward for the first time, which allowed me to survive to the end. It is true that I have sometimes lived frightened. I have to recognize that now I prefer to write rather than draw, I enjoy more and it seems to me a job to draw.

Your way of writing and drawing is much more complex in the latest work than in Blankets.

Yes, Blankets was a very simple, small and intimate story, and I wanted to use as many pages as possible to tell it. In addition, the landscape was in the snow, it was very minimalist. With ginseng roots the opposite happens. I had a lot of information, and I had to synthesize it. I have published it in series EE.UU. And each section had 30 pages. I had to put everything in that number of pages and it was a great exercise. I told him to shorten me. Somehow, I've had to do what they do in mainstream comics, to tell you everything I've ever been able to.

What did you feel like at the end of the comic book you just

presented?First of all, I felt satisfied. With the previous comics, I've never felt anything like that. In addition, my last ten years have been difficult, and at the end of the comic book, I didn't have the energy I saw to follow. However, after several days of presenting tour around Europe, I am once again feeling the inspiration. I've come up with the idea of creating a new book, crazy and epic. My editor wants me to do something short, but I have in mind a 600-page book. Maybe I can do trilogy. I think of the great books, perhaps because in my house of faith there was no more than the Holy Bible. That's the measure of my books -- (Laughter).