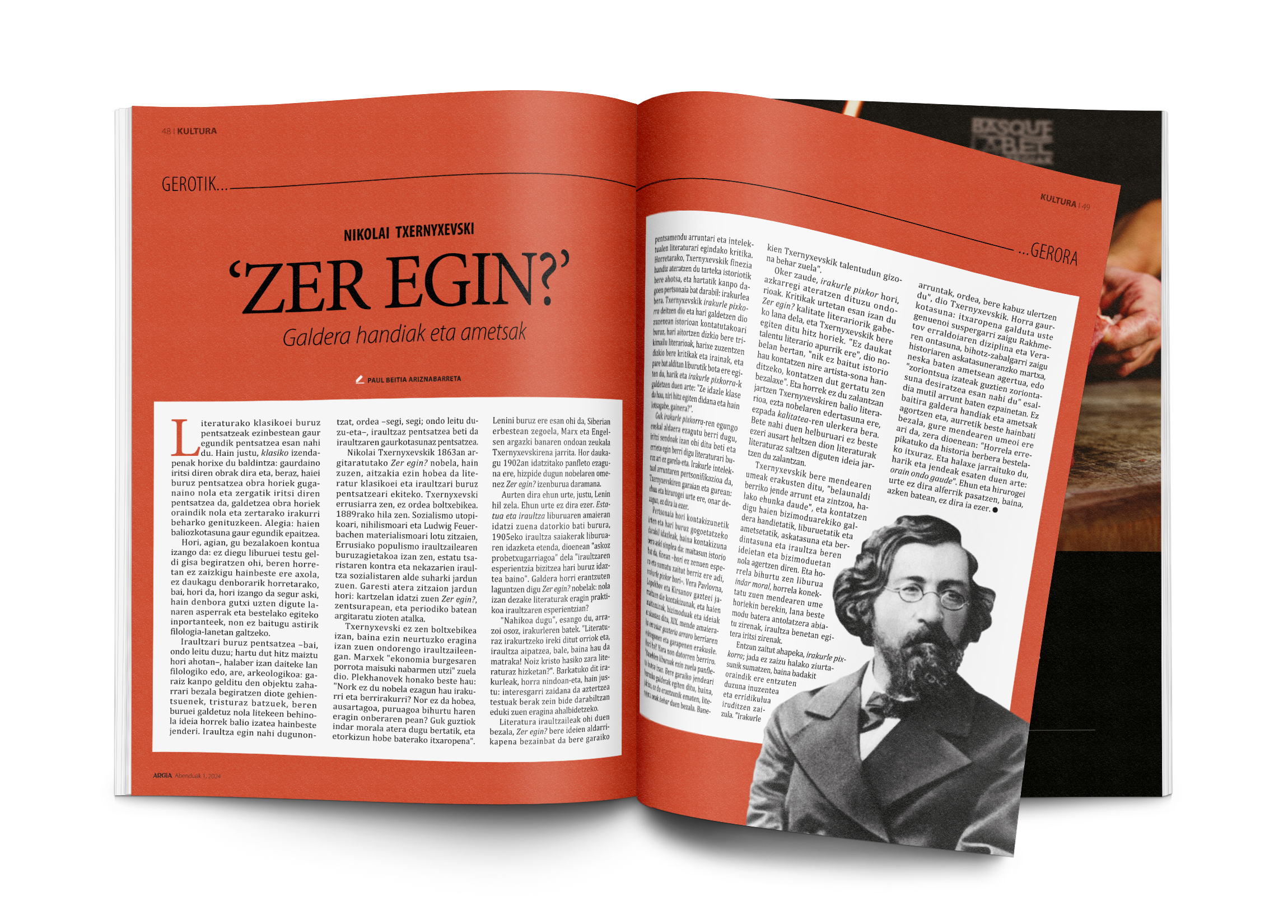

Thinking about literary classics necessarily means thinking from today. It is precisely the classical name that is conditioned to the fact that these works have come to this day, so to think about them is to think about how and why those works have come to us, to ask how and for what purpose those works should still be read. In other words, to judge its validity from today.

Maybe that's the thing we are: we don't usually look at books as stagnant texts, we don't care so much, we don't have time for that, yeah, that's, surely, what it's going to be, we're left so little time for the boredom of work and other important tasks, we don't have time to lose ourselves in the tasks of philology.

To think about revolution -- yes, you've read it well, I've taken that word broken in my mouth -- can also be a philological or even archaeological work: almost everyone looks like an old object that's been out of time, some with sadness, wondering to themselves how it might be that in another time that idea is worth so many people. But for those of us who want to make the revolution -- it goes on, it goes on, because you've read it well -- to think about the revolution is always to think about the present day of the revolution.

Posted by Nikolai Chernyxevski in 1863, What to do? The novel is indeed a perfect excuse for addressing the thinking of literary classics and revolution. He was Russian, but not Bolshevik. He died in 1889. It was linked to utopian socialism, nihilism and materialism of Ludwig Feuerbach, was one of the leaders of the Russian revolutionary populism, fiercely fought against the tsarist state and the socialist peasant revolution. This performance cost him a lot of money: he wrote in jail under censorship Zer Egin, and in a newspaper they published fragments.

Chernyxevski was not a Bolshevik, but it had an incalculable effect on the revolutionaries who followed him. Marx says that he "mastered the failure of the bourgeois economy." This is another case of Plechanov: "Who hasn't read and re-read this famous novel?" Who has not become better, bolder, purer under its kindly influential influence? All of us have removed from it the moral strength and hope of a better future." It is also said of Lenin, in the exile of Siberia, who was next to two photographs of Marx and Engels, that of Chernyschevski. Here we also have the famous pamphlet written in 1902 in tribute to the novel we talked about What to do? Title.

A hundred years ago, quite rightly, Lenin died. A hundred years is nothing. What he wrote at the end of the book State and Revolution comes to mind when he says that "it is much more profitable to live the experience of revolution than to write about it." It helps us answer this question, what to do? novels: How can literature have a practical influence on the experience of revolution?

"Enough is enough," some reader will rightly say. "I've opened these pages to read literature. Just mention the revolution, but here's the snake! When are you going to start talking about literature? ". The reader will forgive me, as it followed me, what interests me is to analyze the ways in which the text itself influenced.

As revolutionary literature tends, what to do? It's both a vindication of their ideas and a critique of the common thought of their time and the literature of intellectuals. To do so, Chernyxevski draws his voice from history with great delicacy and uses a character alien to it: the reader himself. Chernyxevski calls him a poor reader and asks him directly about what he has told in history, confesses his literary works, corrects his criticisms and insults, and even throws him out of the book on a couple of occasions, until the deficient reader asks: "What kind of writer is this, who speaks to me, and so discarded?" ".

We have just known the current Basque variant of the pixactive reader, which always has strong opinions and has just rebuked us for not talking about literature. It is the personification of the ordinary intellectual reader, in the times of Chernyschevski and in our own: no one hundred and sixty years more, let us admit, are almost nothing.

The writer uses this character to get out of the story and reflect on it, but the story is quite simple: it's a love story, after all -- you didn't wait for it and I've heard you again, rogue reader. The story follows the young Vera Pavlovna, Lopukhov and Kirsanov and shows their loves, their ways of life and their ideas as a sign of the concerns and developments of the strange Russian youth at the end of the 19th century. Yes! Here it comes back. -I knew the book couldn't be a pamphlet. He asks questions about the people of his time, but of course he doesn't give answers, as good literature needs. I knew that Chernyxevski needed a talented man.

You are wrong, reader, draw the conclusions very soon. Criticism has said for years what to do? It is a work without literary quality and Chernyxevski endorses these words. "I don't have a single literary talent," he says in the same novel, "because I don't tell this story to increase my reputation as an artist, I tell how it happened." And that doesn't question the literary value of Txernyxevski, or the beauty of the novel, but the understanding of quality. The literature that dares to something more than the objective it intends to accomplish questions the idea that they sell us from the literature.

Chernyxevski shows the children of his century, "ordinary and honest people of the new generation, there are hundreds of them," and tells us how freedom and equality and revolution appear in his ideas and ways of life from big questions, books and dreams. And this is how the book became a moral force, this is how it connected with those children of the century, who launched to organize the work differently, who actually made the revolution.

I listened to you in a low voice, reader, a bit astonished, but I know that still what you hear seems innocent and ridiculous. "But the ordinary reader understands it by himself," says Chernyxevski. Here's the thing: those of us who thought we were desperate rekindle the discipline of giant Rakhmetov and the goodness of Vera, encourage us to march towards the freedom of history, into a girl's dream, or the expression "being happy means wishing everyone's happiness" on the lips of a normal kid. Because the big questions and dreams and, like so many others, the children of our century are not exhausted, when he says: "This is how the same story will be repeated in a different aspect. And so it's going to continue until people say, "We're fine now." One hundred and sixty years are not wasted, but at the end of the day they are almost nothing.

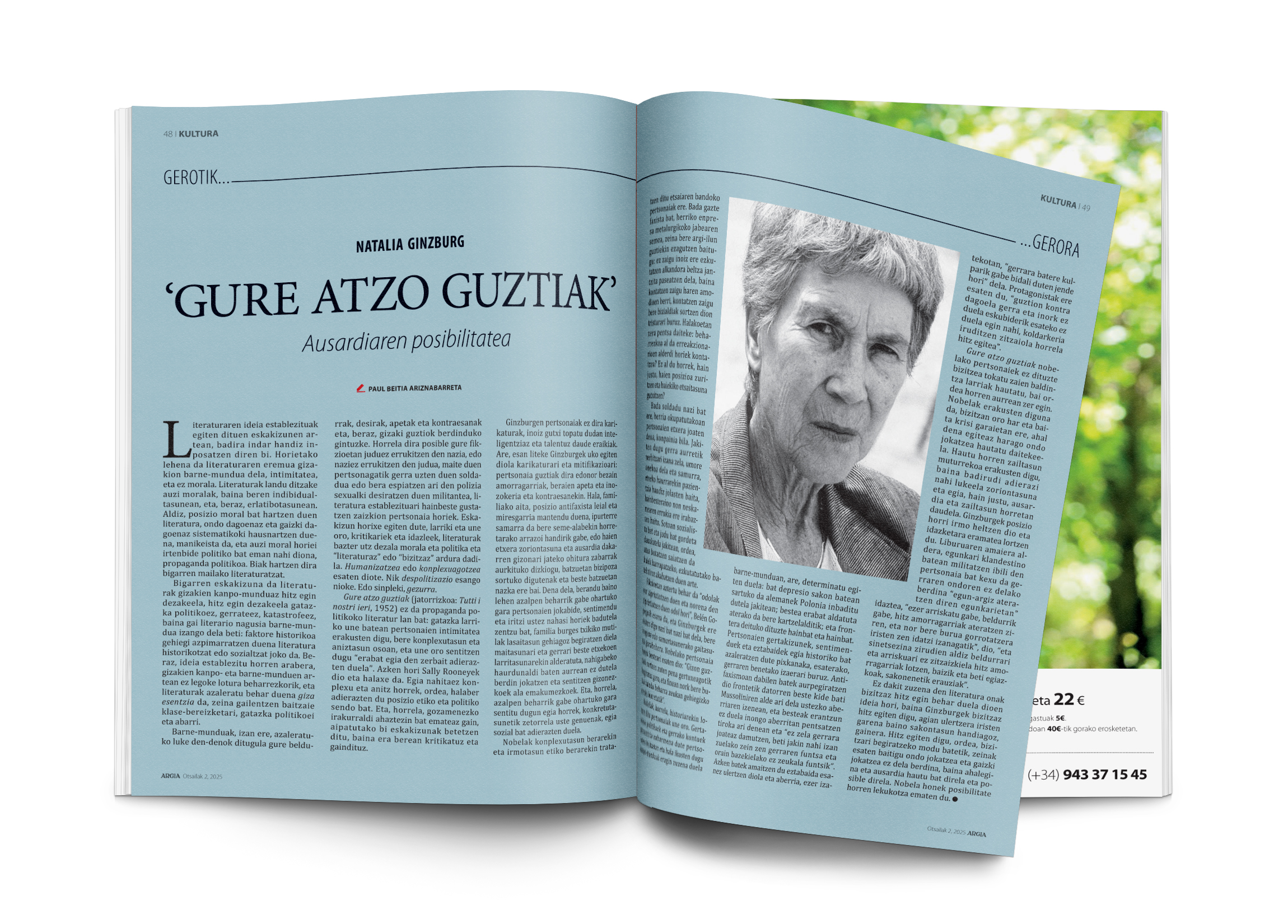

Literaturaren ideia establezituak egiten dituen eskakizunen artean, badira indar handiz inposatzen diren bi. Horietako lehena da literaturaren eremua gizakion barne-mundua dela, intimitatea, eta ez morala. Literaturak landu ditzake auzi moralak, baina beren indibidualtasunean,... [+]

Joan Tartas (Sohüta, 1610 - date of unknown death) is not one of the most famous writers in the history of our letters and yet we discover good things in this “mendre piece” whose title, let us admit it from the beginning, is probably not the most commercial of the titles... [+]

Let's talk clearly, bluntly, without having to move later to say what I had to say: this game, which consists of putting together the letters in Basque, happened to Axular. Almost as soon as the game is invented, in such a way that in most of Gero's pages the author gives the... [+]