"Words are stones for Ernaux and the writing knife"

- The writer Annie Ernaux (Lillebonne, Normandy, 1940) has translated into Basque a book of interviews in which she reflects on her poetics and function: Writing is a knife (Katakrak, 2024). During the interview, in addition to commenting on Ernaux's aesthetic and political options, the importance of translation into Basque will be carefully discussed.

Last year you finished the degree in Translation and Interpretation, and even if you translated some short text, this is the first book you brought to Euskera: Writing is a knife. He presented it recently with Katakrak. What has the experience been like? The

translators spend a lot of time working with the text we have to translate, with the author…, as we create a close relationship. In my case, it was a pleasure to spend months with Ernaux. Furthermore, I feel that it has been a round book, very enriching, precisely because the writer himself speaks of his poetics, and that has helped me a great deal in the translation process, to somehow respect his writing and make my choices.

It is a singular book, both in terms of gender and content. What would you highlight?

It is not like the other books by Ernaux that have so far been brought to the Basque country. It's a kind of essay about how Ernaux understands writing. For about a year the writer Frédéric-Yves Jeannet asked Ernaux how to understand writing, where he places it in his life, what functions they assign him, what characteristics his writing project has... For those who know Ernaux, it is a way to know more; and for those who do not know it, it is a way to approach their literature.

The editorial itself Katakrak has proposed to translate this book. Do you think he's chosen him for those characteristics?

Yes, because it is an eminently political book, close to the essay genre. Ernaux’s literary work is interesting and disruptive, it is, to say the least, the material result of his writing work. But all that's behind this activity is interesting. And that's not just the author, but also where the author is.

Go further: What breaks Ernaux's literature?Content and form

are often seen as two extraordinary things. Ernaux is a breaker in both directions and even defends that they cannot be separated. As he explains in the book, he has not chosen the form because aesthetically it seems more “beautiful”, but the content itself has “determined” it. Writing is very rigorous, accurate, no decorations. As for the content, part of his life, memory and subjectivity to speak under a condition: Ernaux is a woman of working-class origin and this awareness determines her writing.

This system drowns people like her and those who appear in her books, from the working class. Putting your voice in the literature brings out the contradictions of society. However, he wants to tell everything in a non-populist way. I could write very romantically, idealize being poor, but not: look for a story as objective as possible, as close as possible to the truth.

Ernaux is explicit in his intentions, he does not hide the political objective of his writing.

So it's interesting to me. Not so much his figure expressly; Ernaux may have opinions that I do not entirely share or that raise doubts. Some of the things he says are interesting, because in our case we can use them to make their own thoughts. For example, when Frédéric-Yves Jeannet asks him directly about political commitment, Ernaux replies that the best thing he can do as a political action is write, yes, but it is not the only thing he does and cannot be limited to that political commitment. I think that is what we must stress: that commitment must go beyond writing, that the writer has no superpowers. In the same vein, it does not accept the position of those who say that literature is only a matter of aesthetics, which has nothing to do with politics.

There is often talk of a supposed autonomy of art. It's thought that art can't master anything. Interestingly, domination is understood, and that is why, for example, art is neglected for the sake of certain political movements or purposes, but not subject art to the market.

This debate, between art and politics, is becoming more important in recent years in Euskal Herria, and fortunately there are people who have a proposal about the political function of art. You have to move away from thinking that art or writers are something apart, something almost mystical. As Ernaux says in the book, literature can serve to ruin or perpetuate order, and no one can escape that.

"You have to move away from thinking that art or writers are something apart, almost mystical. As Ernaux says in the book, literature can serve to ruin or perpetuate order"

The book is called Idazlabana bat da. What do you mean?

Ernaux, by himself, is not a great lover of metaphor, but has excellent comparisons. It does not abuse, but when it is used it is rigorous. He says words are stones for him and a calligraphy knife. The expression in Basque could be otherwise, evidently, perhaps more grammatically appropriate. “Writing is like a knife,” for example. But I've chosen to do it that way, intentionally. In this way I wanted to refer to the quote of Gabriel Aresti, well known in the Basque Country: “Poetry is a hammer.” Bertol Brecht also said that art is a hammer, and that's well known. I dare say that everyone understands the political function of art equally. All three believe it can be a tool to transform the world.

They say Ernaux's wording is severe. Jeannet has used the clinical word, Ernaux himself has used the knife. Someone might say it's cold, unaffectionate. It is of professional origin and the syntax and lexical one who has learned at home is the one who uses it. “No adornments,” in his words. It's also the hallmark of a class language. It also has elements from Normandy. Here's a quote from the book: I used the lexicon that uses illegitimate languages, popular syntax. The Basques may not receive it in full, we are not reading it in French obviously, we do not have the same literary and cultural references as the French.

In that sense, I had an internal conflict when I had to make decisions to translate the book. In the end, I think that the road taken is round: I have translated the work in Eastern Basque, in a kind of Navarro, and also for an editorial from Pamplona. In Ernaux, it is possible to consider a peripheral literature, such as the translation in relation to literature, how working women are on the periphery, and I have tried to sewing the translation with these peripheral elements. I felt very arrogant when I came back from Ernaux. For the things he says, I felt it was OK for me to do it in my Basque country.

Ernaux says that he seeks the “truth”, which is part of subjectivity, but which does not fall into psychism: he seeks sociological and political truth. What it does is called auto-socio-biography. He refers to Brecht to explain it: “To think about others and others in him.” Yes, pulling away from what I've said, it does autobiography, but it stops being a car because it describes a sociology, because

it shows the collective reality of people in a sociology. This purpose makes his work self-socio-demographic. Only thus does it make sense to talk about the self, because it is when it tells the focus, not on the individual. Anyone can be. When he chooses what to write, I think he doesn't do it from his own interest: shame, he decides to do about what has caused him social stigma, and it's not easy, but it has a function.

In addition, it is interesting to think that the moment we bring it to Euskal Herria and to Euskera, the function of their texts changes a little: French society and the historical moment, or current society, are not equal. Some Basque writers have said this, that they have noticed the ever-better reception of their works, that the public now connects more than ten years ago.

What do you think, what reception has Ernaux's literature had in the Basque Country?

Perhaps he would relate it to the dimension that the case of gender has acquired. He's a writer who writes clearly from his condition. What is he? Woman of working-class origin. From there, he always writes conditioned. I think since 2022, when he won the Nobel, Ernaux has had a boom. It's no coincidence. The transformation of society has made it possible. I mean, if I had won the Nobel Prize twenty years ago, I don't think I had the welcome and influence that it has today in Euskal Herria, and that's because there are now conditions for these kinds of issues. I suppose that the Basque standard reader you know of Ernaux did not reject it as a sector in France has done. On the contrary, it seems to me that it has been well received and that is why there has been a boom. Many readers have read his books, many Basque writers have said that Ernaux is a referent. The number of translations shows that there has been an influence, even on the writers, on the creation of original texts.

Eider Rodriguez has been one of the authors who has spoken about the influence of ERNAUX in her literature.

Yes, he has frequently mentioned Ernaux among his references, and he has made a magnificent preamble. I think he told everything he had to say about Ernaux, in a nutshell. I don't want to go ahead any further, so that people can read.

"[In the Basque translation] I do not know why generational change has not taken place in such an explicit way, but I think it has to do with the political landscape"

Ernaux first brought to the Basque country in 2002.La Passion Pura (Igela, 2002) was translated by Joseba Urteaga, written in 1992. Since then, six novels have been translated by Urteaga himself, as well as by Gema López Las Heras, Itziar de Blas and Xabier Aranburu. This year the Memory of a girl translated by Aiora Jaka (Igela, 2024) has also been published.

In the early 2000s, three of his books returned, and then the discontinuous, almost ten years old, and then the same. There's almost one translator per book. I think that is right. The Basque literary system is weak, we must bear in mind that we are talking about the literary system of a minority language, and the translation has a quite special function in this case, when we talk about Basque literature. The translation here is characterized by the conditions of the Basque Country and the Basque language. So the rhythm of translations is often messy. It is done as best as possible, but there is not always the possibility of returning what readers demand at the moment.

Does the new generation come to Basque translation?

Yes, a generational shift is taking place and more and more is being said about it. In addition, it is, fortunately, planned to facilitate the path to new generations. For example, the new Miñaberri scholarship is there. I don't know why generational change has not happened so explicitly before, I don't know how to analyze it, but I think it has something to do with the political landscape. It is nice and enriching, but it is true, I think it was something that could not stop happening. I would say it's a generational change that comes from need. It is, of course, a good thing that the translation profile is changed and that it is very varied.

However, with this I do not mean that we have to reject the previous generation. On the contrary, I admire very much the work they have done and are doing and I still have a lot to learn. It must also be stressed that it has been a very militant piece of work. And I believe that the translators we have come to follow this tradition, coming back from political consciousness to Euskera, at a time when disrespect and hopelessness unfortunately prevail. I also believe that translation has contributed a great deal to the Basque literary system, which is vital, because it has contributed a great deal towards consolidation and stabilisation. Perhaps we should now be thinking about the challenges that arise at the moment.

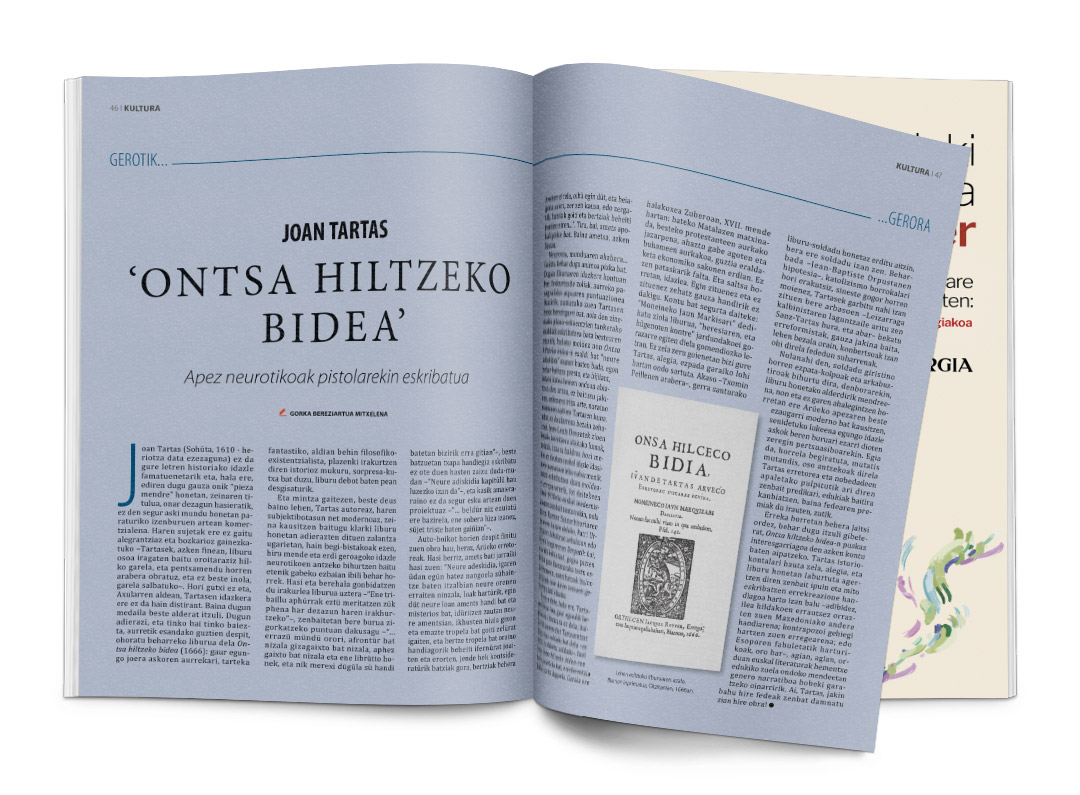

Joan Tartas (Sohüta, 1610 - date of unknown death) is not one of the most famous writers in the history of our letters and yet we discover good things in this “mendre piece” whose title, let us admit it from the beginning, is probably not the most commercial of the titles... [+]

Beware of that view of the South. Firstly, to demystify the blind admiration of the green land, the white houses and the red tiles, unconditional love, fetishism associated with speech and the supposed lifestyle. It leaves, as Ruper Ordorika has often heard, a tourist idea... [+]

ilbeltza-(1).jpg)

.jpeg)