Video clips: face or cross

- Their job is to create and play music. But just that? Image and promotion are becoming more and more important in most areas, and musicians are not apart from that swirl either. A video clip is the (almost) essential support for publishing a song or a record. Yes, at least when it is intended to extend the work more than normal. It is also a resource for adding more layers to the musical proposal. But it requires an effort, both in money and in time. We have targeted five musicians.

This is the second part of a series of reports. In the first, we analyze video clips from the point of view of videochists (number 2,864).

We must not go too far back in time. For many years, radios have been the way to present the new song or album to the public square. They are still, but if we have a member of a management company or a team that knows the networks well enough, the complementary proposal will come quickly: “If we want to give it some strength, we should make a video clip.” Musicians are in the need to answer that statement, which hides a question. Uxue Amonarriz acknowledges this. “There is an unwritten law that says that to promote a new song or album you need a video clip. And the goal is clear: reach more people.”

Amonarriz is a member of the Huntza group who has just interrupted his career. It cannot be said, where appropriate, that it has not been an effective remedy. Among the video clips made with a song in Euskera, Aldapan gora from the Huntza group is the one that has accumulated the most visits. It's uploaded to two channels, but if you add the two, you've seen almost 20 million times on Youtube. It's the first song that spread and everything started with the radio's surprise. “The company Management advised us to make a video clip and we went to the well-known AZ Gaubela. We did everything in very little time to open it quickly, but we didn’t expect such a welcome.” Amonarriz recalls that it spread widely not only in the Basque Country, but also in South America and other European countries.

However, the youngest members of Huntza were only about 20 years old, and the logic of the music industry was unknown. They had to learn quickly. “We also came up with a very large wave and in part it was hard to face without drowning. What has often saved us has been humor.” They try to reflect that “spontaneous” humor in their video clips. In this sense, Amonarriz says there have been several promotional actions: “Video clips also serve to approach the public. The first was above all a way of presenting ourselves. Almost nobody knew us and through it he knew who we were, how we were, what worried us…”.

Not even the finest work is a guarantee Many of the video clips that

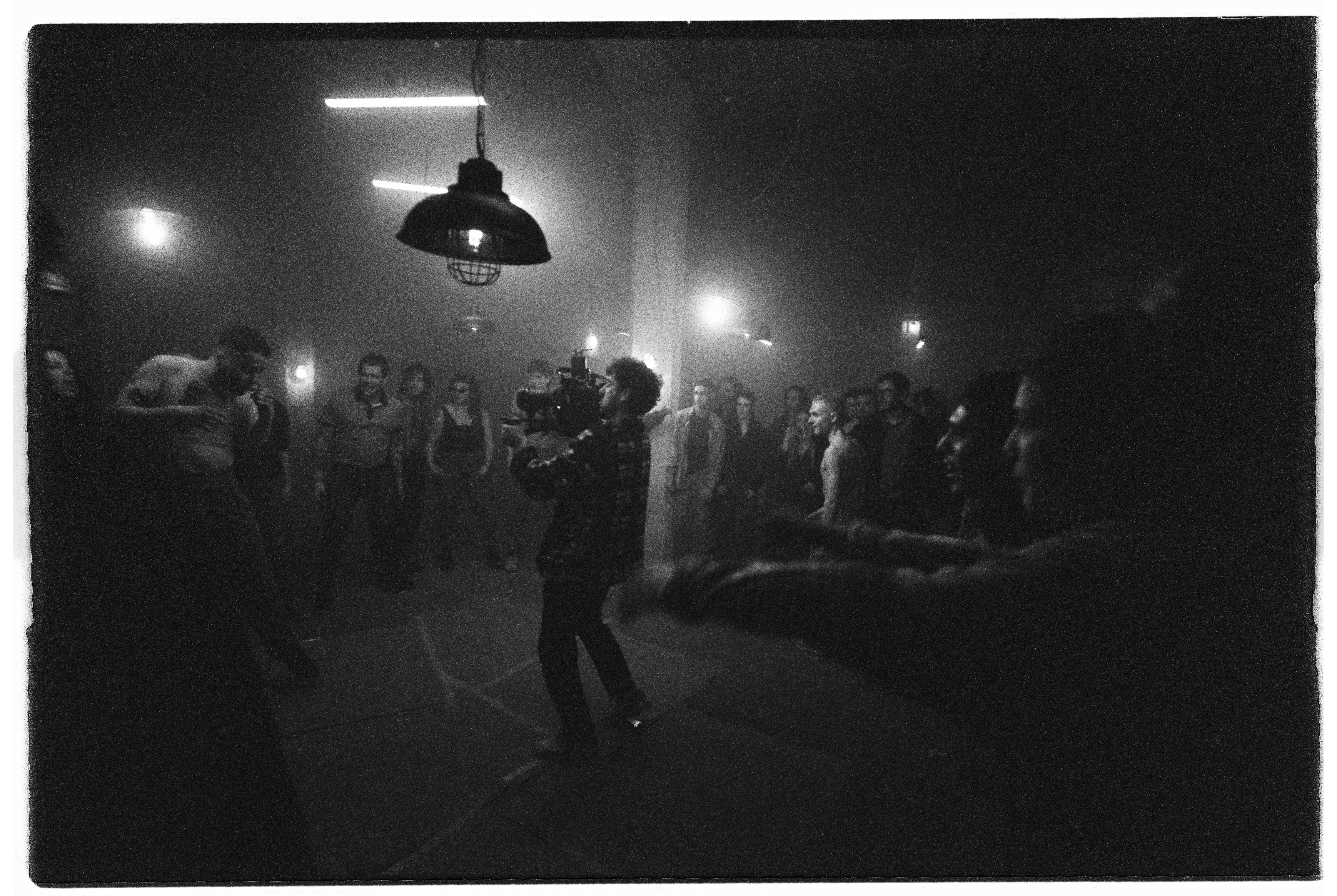

are broadcast here and now are more than just an attempt to place images more or less appropriate to a song. Producers like Arriguri, Badator… have doubled their wager. With an eye on international trends, they have turned the work that originally had more communication instruments into a work of art. With quality resources, whenever possible, but also, when there is no money, from imagination and neighborhood work. However, this does not mean that these video clips made with the artistic gaze do not share the same playing field as others: they are born with the desire to be speakers or drivers.

At least in the case of Iban Urizar. She had already made some previous attempts to make the Amorante project known on video, with the help of the producer Bira and with the vocation to show what she does live. However, at the end of last year he published one of the video clips that he has asked for the most in depth. He put the song Habanera in the hands of the producer Arriguri, who have made a video re-reading. The result seems wonderful. “I had blind confidence in them. Of course, the work is limited by the money you can put as a musician, but they have been very involved and very fond of it.” In this sense, Urizar has felt a point of shame, and an "infinite gratitude," in view of the number of people who have worked in the performance of the video clip of his song. Confess that the video clip added an additional meaning to the song.

Another thing is if the good video clip has opened more doors. Urizar hasn't detected that that song has been heard more than others. This leads to contradictions. “I want the video clips and for me there are too to keep them. But if you don't have a company behind you, you have to pay for your pocket and it's hard to measure whether it's worth it or not. If it’s very active on the net, maybe yes, but I’ll do fifty years and I’m not for that.” Uxue Amonarriz also lives this conflict. He says it used to be enough to predict how much you would spend on the recording studio, but now you have to add the cost of one or more video clips to the “hole” you’re going to do at first. “It’s a bet in the hope of getting more or more direct. That boom that came to us can come, but it's very rare. It’s possible that all your work stays almost nothing.”

Odei Barroso knows this work well that is behind the video of self-production to life and knows what it means to have less power than he wants to pay. “Musicians see elaborate video clips, and that’s what we want, but often without knowing how much it costs or how much work.” That's why, and because attempts with others had not been completely satisfied, he started to self-produce his own video clips. He started experimenting with animated lyric videos (videos with song lyrics), and then going to more complex videos. He has

perfected the songs of ØDEI with what he has learned in a self-taught and progressive way. It has managed, once and for all, to carry out works that reflect its character and intention. That's bad. Record your pieces with a unique camera and a friend with no previous experience. The skill he has now developed puts it at the service of other musicians on order. She lives in the knots of this paradox, which in part started making her own video clips because she didn't have enough to pay others. And now you earn your life by making video clips for others and then "in free time" so you can make your own songs. In any case, he believes that his musical performance has a “point of militancy.”

Barroso agrees with what other musicians have said about the role of video clips: “They are mainly a dissemination tool.” But they can also adopt other meanings. Barroso makes rapa and finds references on the French scene. He says that since the early 1990s, rap was created with images and videos. “There is a desire to reflect the neighborhood or the way of living, to show what is on the edge, and to break with the aesthetics of the rich neighborhoods.” With ØDEI, Barroso has taken this path by taking elements such as clothing or posture. That is true, without showing a reality that is not yours. “I don’t meet guns or a lot of money, or I don’t see my face covered, because I don’t have anyone behind me.”

Therefore, a video clip helps bring a job or a proposal to more corners. But it's not the only way. Although the Ibil Bedi group has barely made video clips, its music has reached a

lot of castles, halls and radios. The few audiovisuals they have made have launched their proposals or made them on their own, experimenting and not spending money. It has not been too conscious a choice, but not everyone has the same vision among the members of the group.

Amets Aranguren is not a fan of the music video, and he is not very interested in what is outside the regular work of the musician. Areta Senosiain, on the contrary, appreciates them, at least when they are well made, but so far they have not felt the need to address them. “It seems that Ibil Bedi has opted for consensus and not for making video clips. That has not been the case, but it is true that we have never tried too much. And when we have tried it, it has not come out as we would.” Both are responsible for changing or limiting the meaning of the song. “There are songs with ambiguous meanings, that the listener forms with his experiences or occurrences; we do not want a video clip to tell us what needs to be represented.”

How long can a musician take to complete a new music video? Paraphrasing the Anelids of Ibil Bedi, this is what worries Senosiain. “If I see someone making a very elaborate video clip, but the song is scarce, it loses many points for me. If the song isn't good, it means you haven't done the right part of your work. And it can be because time has spent on other things. Making video clips, for example.” They, on the contrary, have never had time to dedicate it, because they are working on other work during the week and on the weekends live or creating new songs. “It is true that we have been lucky: we have achieved a space, many concerts, listeners… without making videos. This has given us a lot of work and a lot of work, and has not left us time to watch video clips, etc.” That's right, don't rule out that later on you try, you have an idea in your head.

The tyranny of the Aranguren

image says that we live in an “ultra-fast” society, and that as a group they are not very comfortable with it. In this sense, whether it is a conscious option, it is satisfied with the direction they have taken. He knows that if a new song comes out with a video clip, more people will listen to it, but he doesn't want people to hear it for that. It is said that there are political choices beyond the words of the songs, as this is the case of the members of Ibil Bedi, who do not want to make video clips because they think that what they do will be consumed “faster”.

He has made a lot of video clips, but Uxue Amonarriz is not far apart from Aranguren’s concerns. “Today being a musician is not just being a musician. It’s also selling a project through the image.” The members of Huntza do not like this world of image too much, and they say that they have been strangled in part. “Society also wants to consume it. You have to choose how to deal with it, but it's hard because the spread of your work or your income can depend on it. Many festivals, for example, look at their welcome on Instagram or Youtube to decide whether to invite or not.” This trend reveals that some musicians may be affected. Iban Urizar has the same feeling. “A video clip is an expensive device that serves you to sell. Now, as we are constantly selling, it has become almost indispensable.” However, he would not be able to keep this disease in the same video clip: “You have to continuously sell the image that is tyrannical.”

Odei Barroso has conflicting opinions because the trap of visits and angry clicks. He tells a phenomenon that happens on the French rap scene to explain it: “Management have their own videos. They welcome three young people, make them a video and hire someone who makes over a million quick visits, avoiding the other two.” However, Barroso is determined to keep making video clips. “I don’t want to speak for the convinced. If the video serves to extend our message and character to more places, I want to take advantage of it, even with contradictions.”