Once the industry has run out, what?

- Beriáin (Navarra), February 1974. The workers of Potas de Navarra made a strike, among other reasons, for the strike of the staff of Motor Ibérica the previous year. It was not, therefore, the first strike by the Navarre industry, not even by Potas. But Potas was the largest company in Navarre, with over 2,000 workers and one of the strongest trade union movements in the territory. In addition, 50 years ago, they led a new form of protest: the closure of workers in mines. During that initial strike in 1974 187 workers remained closed inside the mine for 70 hours.

In that autumn more mobilizations took place and in early 1975, along with the participation in the general strike, the second, much longer, closure took place since 7 January, 15 days. The repression of the Civil Guard was very harsh, such as measures against the strikers: fines, 30 days in prison, unemployment… Only some workers were able to return to work after the 1977 amnesty. But the closure had a great impact outside Navarre and caused a flood of solidarity.

Depleted industry

But Potas de Navarra had an expiry date. Ten years later, the company closed at the end of 1985, depleting the potash source. Potaries de Subiza was opened, with 533 workers, but in a few years it was also closed. And besides the mine, in general, the industrial model prevailing since the 1950s was exhausted. The industrial reconversion launched at the beginning of the decade by various European governments, including Madrid, had a great influence on the main industrial centres of Hego Euskal Herria. Deindustrialization revolutionized the labor movement.

The last physical footprints of the production plant of Potas de Navarra were demolished in the decade of 2010 and it was not the only case, like the plant of Superser, a reference in the industry of the Comarca of Pamplona, which was demolished in 2019. “The demolition of old factories makes the history of deindustrialization, the social consequences, the footprint left on workers and their families, environments and communities invisible,” says Pérez Ibarrola

The last issue of the journal, edited by the Association of Historians of Navarra, Geronimo de Uztariz, refers to the industrialization process in Navarre, and gathers, through various examples, what this process influenced the labor movement. Mobilizations in the factories of Navarre in the early 1970s show that they were mainly carried out to demand wage increases and improved working conditions, that is to say, to advance rights. However, in the following decade, when unemployment, which until then was cyclical, became endemic, the mobilisations were aimed at minimizing setback, maintaining conditions or the job itself as far as possible. The labor movement had to start the defense, since it could not continue.

In the journal Geronimo de Uztariz, the historian of the UPNA, Nerea Pérez Ibarrola, states that deindustrialization has been analyzed from the economic perspective, but that it had an important social impact and that to work the working class from this perspective it is necessary to open new lines of research. And it also talks about the importance of protecting industrial physical heritage to drive memory.

The last physical footprints of the production plant of Potas de Navarra were demolished in the decade of 2010 and it was not the only case, like the plant of Superser, a reference in the industry of the Comarca of Pamplona, which was demolished in 2019. “The demolition of old factories makes the history of deindustrialization, the social consequences, the footprint left on workers and their families, environments and communities invisible,” says Pérez Ibarrola. “Abandoned factories retain the memory of the social antagonisms that lived and lived in our society. Maybe that's why they're so uncomfortable, because their negative impact is not just visual."

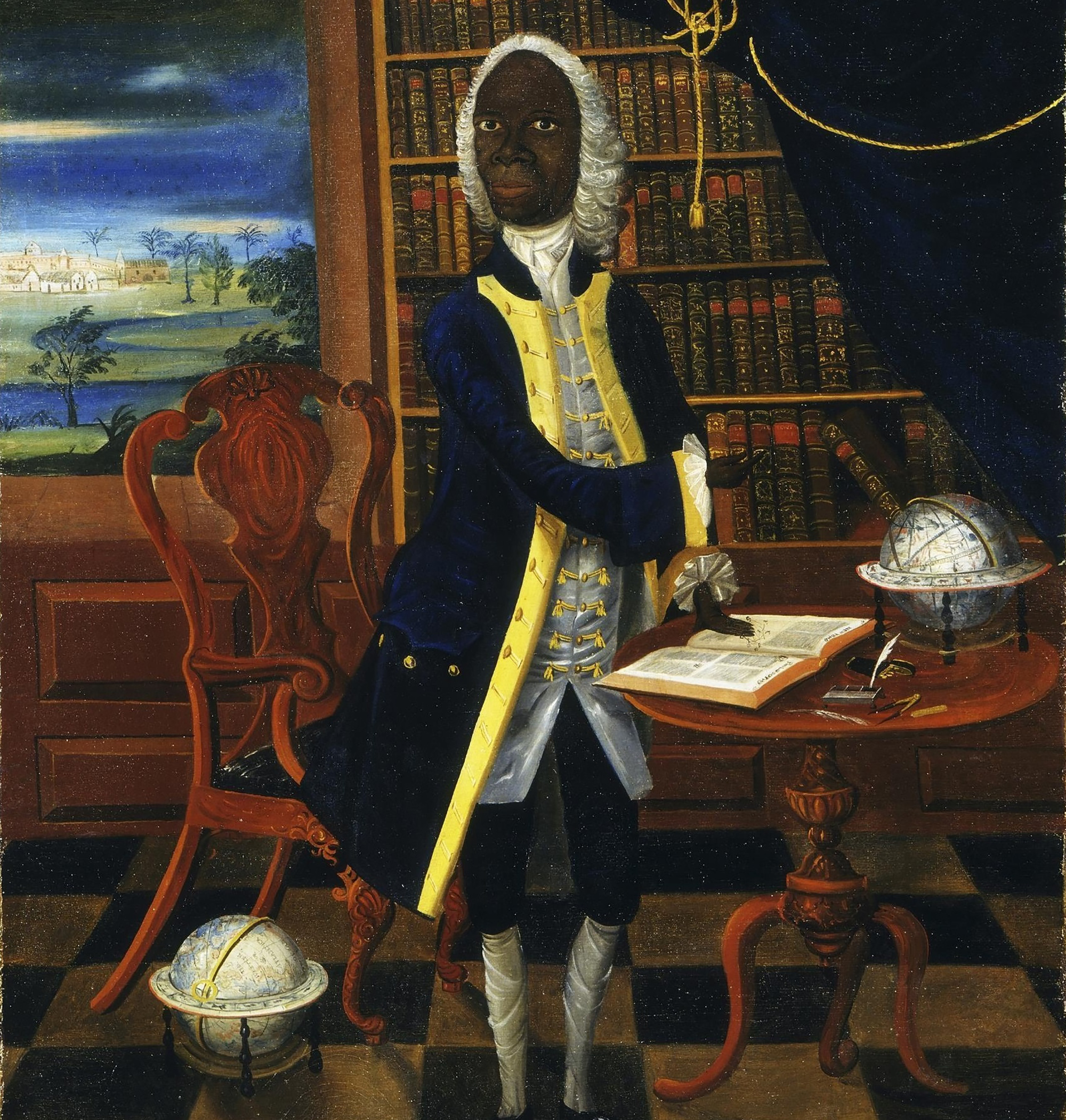

London 1928. At the Victoria and Albert Museum there was a very special painting: in the painting there is a black man, with wig and Levite, surrounded by books and scientific instruments. Thus it was catalogued in the Museum: “Unique satirical portrait representing a failed... [+]

Ethiopia, 24 November 1974. Lucy's skeleton was found in Hadar, one of the oldest traces of human ancestors. The Australian hominid of Australopithecus afarensis is between 3.2 and 3.5 million years old.

So they considered it the ancestor of species, the mother of all of us. In... [+]

A group of archaeologists from the University of Berkeley, California, USA. That is, men didn't launch the lances to hunt mammoths and other great mammals. That was the most widespread hypothesis so far, the technique we've seen in movies, video games ...

But the study, published... [+]

Zamora, late 10th century. On the banks of the Douro River and outside the city walls the church of Santiago de los Caballeros was built. The inside capitals of the church depict varied scenes with sexual content: an orgy, a naked woman holding the penis of a man… in the... [+]

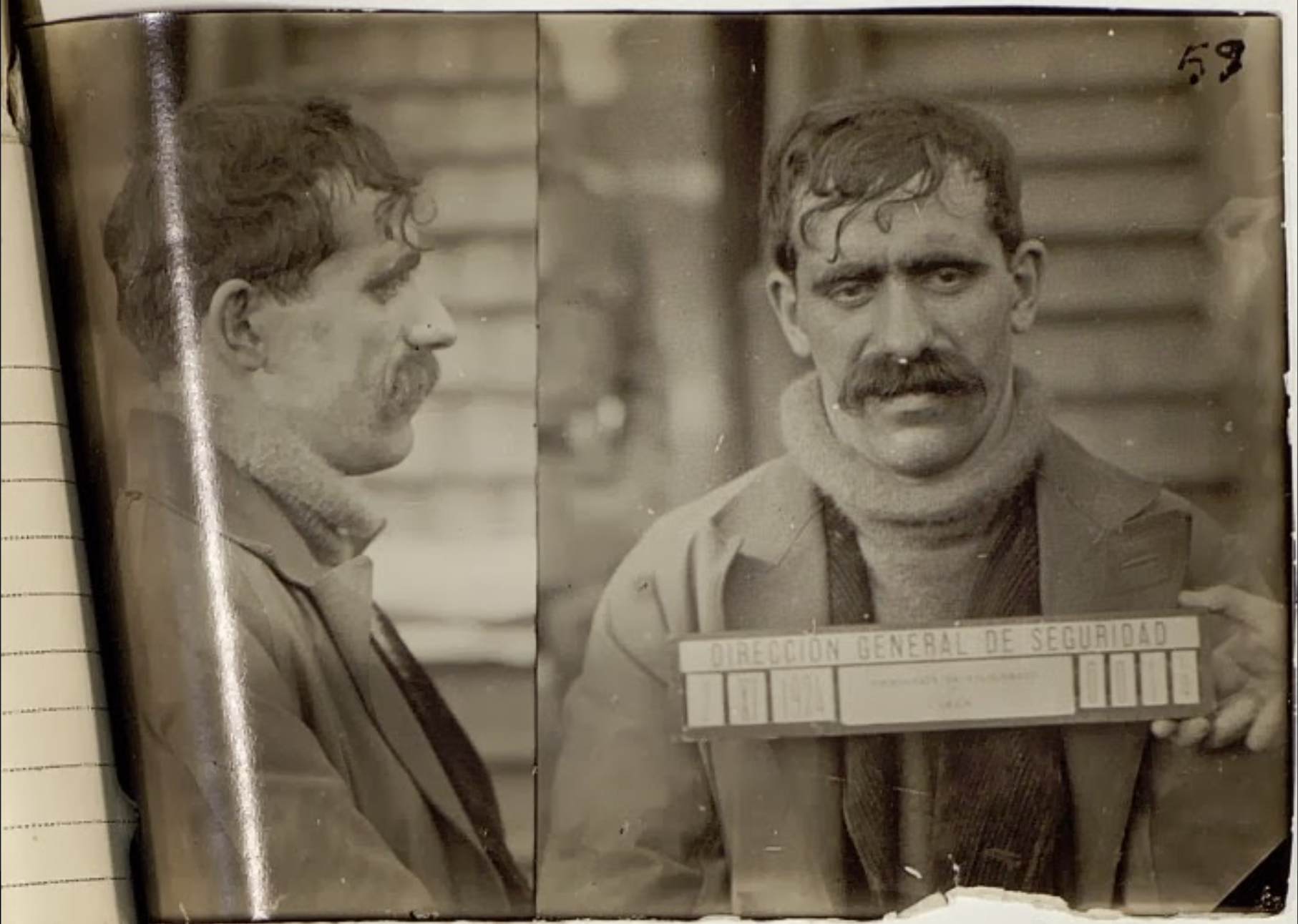

Born 7 November 1924. A group of anarchists broke into Bera this morning to protest against the dictatorship of Primo de Rivera and to begin the revolution in the Spanish state.

Last October, the composition of the Central Board was announced between the displaced from Spain... [+]

Washington (EE.UU. ), 1807. The US Constitution banned transatlantic slave trade. This does not mean that slavery has been abolished, but that the main source of the slaves has been interrupted. Thus, slave women became the only way to “produce” new slaves.

So in 1845, in... [+]

A group of interdisciplinary researchers from the Free University of Berlin and the Zuse Institute have developed a complex mathematical model to better understand how Romanization spread in North Africa.

According to a study published in the journal Plos One, the model has... [+]

While working at a site in the Roman era of Normandy, several archaeology students have recently made a curious discovery: inside a clay pot they found a small glass jar, of which women used to bring perfume in the 19th century.

And inside the jar was a little papelite with a... [+]

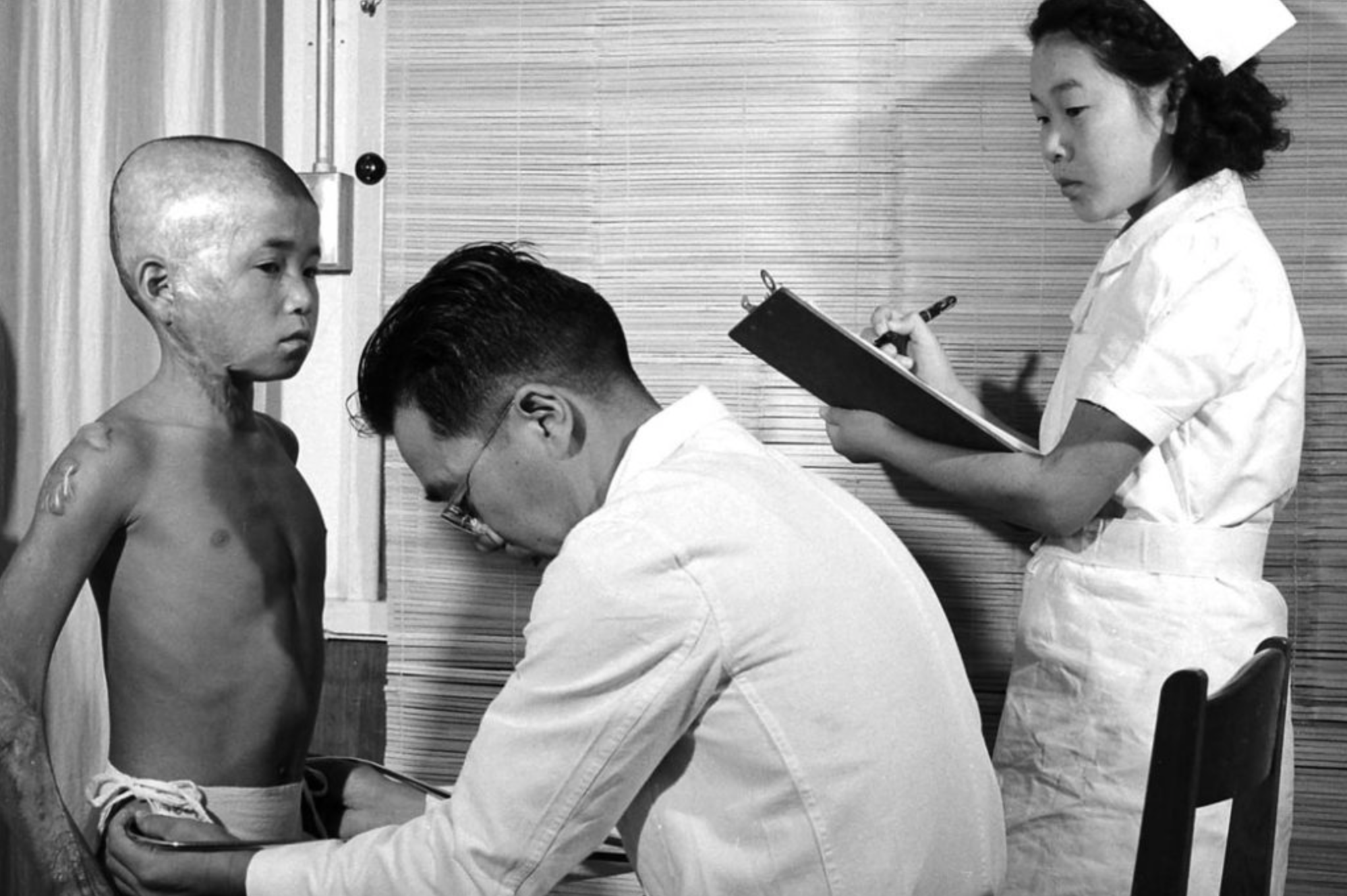

Japan, 6 and 9 August 1945, the United States launched an atomic bomb causing tens of thousands of deaths in Hiroshima and Nagasaki; although there are no precise figures, the most cautious estimates indicate that at least 210,000 people died at the end of that year. But in... [+]

A team of researchers led by the Japanese archaeologist Masato Sakai of the University of Yamagata has discovered numerous geoglyphs in the Nazca Desert (Peru). In total, 303 geoglyphs have been found, almost twice as many geoglyphs as previously known. To do so, researchers... [+]

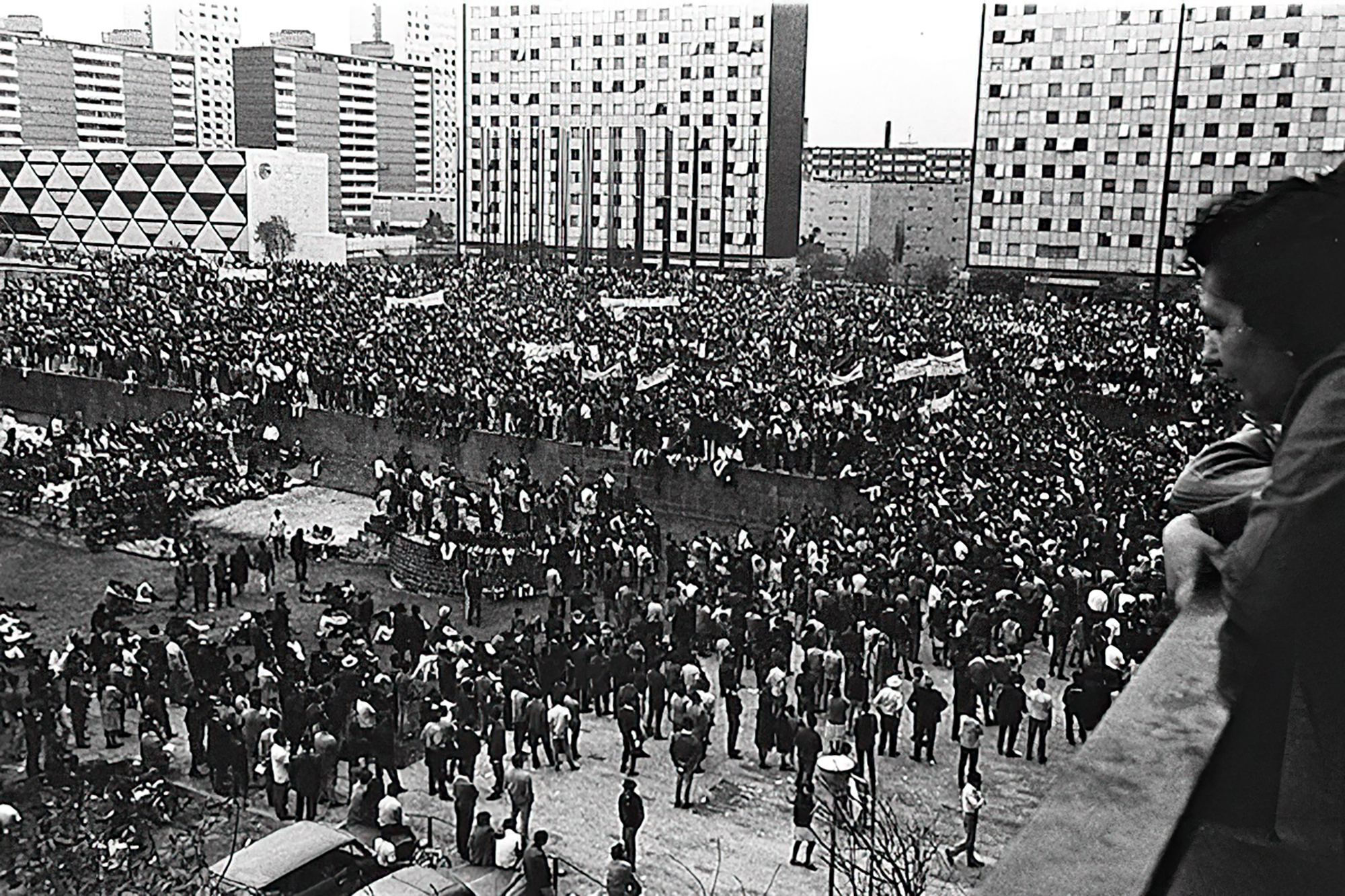

Born 2 October 1968. A few months earlier, the student movement started on June 22 organized a rally in the Plaza de las Tres Cultura, in the Nonoalco-Tlatelolco unit of the city. The students gathered by the Mexican army and the paramilitary group Olympia Battalion were... [+]

On the northern coast of Peru, in the deposit of Diamarca, mochica culture (c. 330-H. C. 800) have found a trunk room. This culture is known for its impressive architecture, vast religious imaginary and colorful walls full of details.

The room found confirms these... [+]

Tijarafe (Canary Islands), mid-14th century. When the first Catholic monks came to the area of the island of La Palma, the Awares, the local Aborigines, saw that they worshipped the sun, the moon and the stars.

And this has been confirmed by the archaeological campaigns carried... [+]

Maule, 1892. Eight women from the Salazar Valley headed home from the capital of Zuberoa, but on the way, in Larrain, they were shocked by the snow and all were killed by the cold. Of the eight, seven names have come: Felicia Juanko, Felipce Landa, Dolores Arbe, Justa Larrea,... [+]