"The violence of slavery was fundamental in the rise of capitalism"

- American historian Marcus Rediker explores the beginning of resistance to capitalism until he reaches the history of seafarers and piracy.

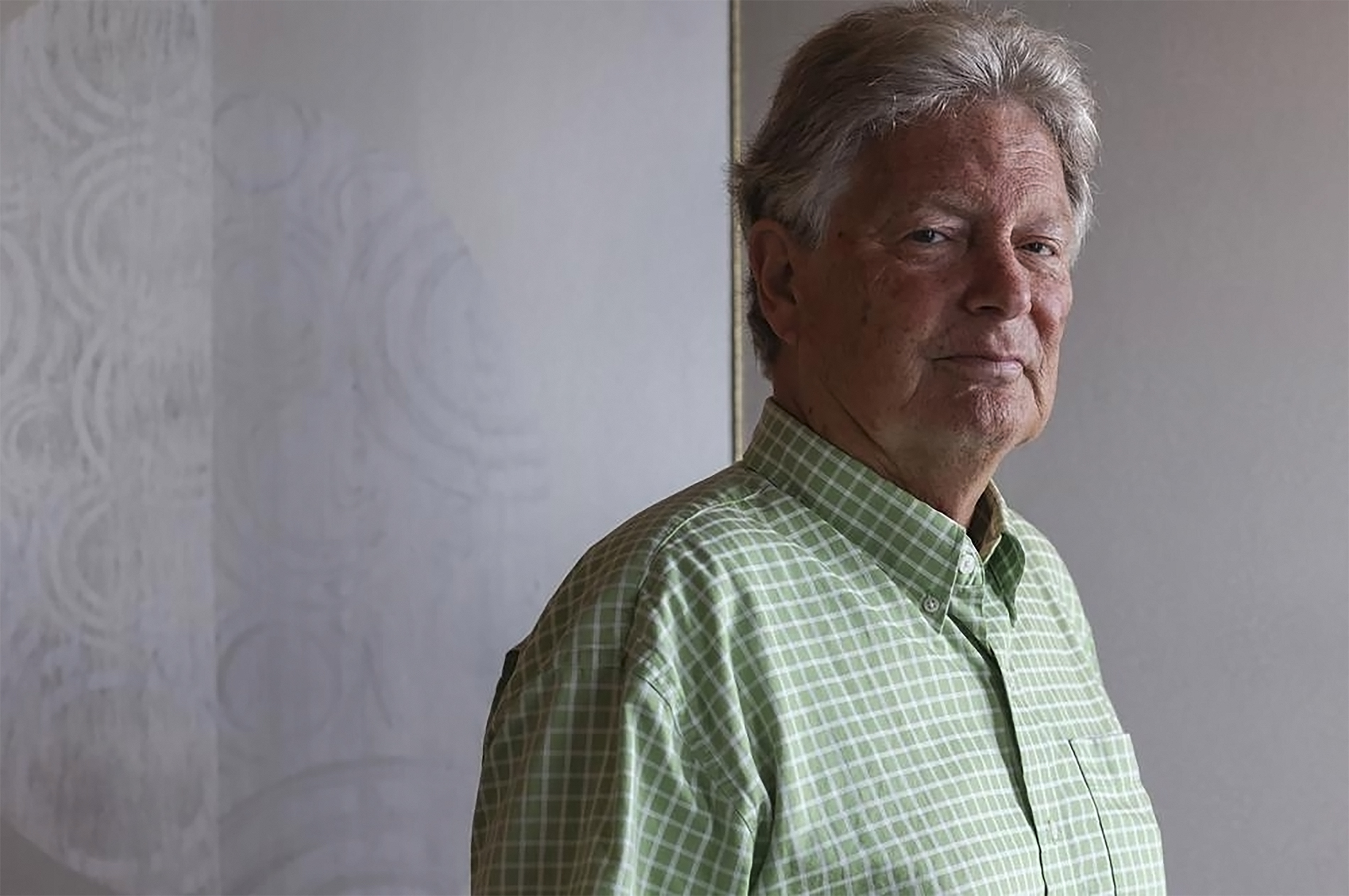

Marcus Rediker (Owensboro, Kentucky, 1951) states that the slave journey transformed what made that journey. Seamen, whatever their origin, became "whites" throughout their career, and were able to use violence against blacks, enslaved by kidnappings, threats, torture, rape and mines.

Rediker has not confined himself to checking this transformation, but wanted to investigate how social relations at sea have changed the world. It was a destructive transformation, but it has also wanted to explore the cultural changes, resistance and alliances that existed between different people when the uprisings took place, within the general context of the terror that accompanied the birth of modern capitalism.

From these investigations have emerged some books that have recently been translated and published in Spanish in the Spanish state. Among them are The Hydra of the Revolution (Hydra of the Revolution, Traffickers of Dreams, 2022), written in four hands with Peter Linebaugh, and the most recent, Villains of all nations (Villains of all nations, Traffickers of Dreams, 2023), an entry into universal history, told by work, life and death in the oceans. This framework allows Rediker to step out of the strict vision of national states to deepen history from below, and E.P. Share this way of approaching history with Thompson and Eric Hobsbawm or his colleagues at Midnight Notes Collective, Linebaugh and Silvia Federici.

What does it mean to investigate "history from below"?

To access history, you have to put yourself in the personal center of detail. They're left out of the books, because they almost always tell the story from above. There are kings and queens, presidents and, in general, great white men. From the bottom, history acquires a more democratic and inclusive view, because everyone counts. You put your employees in the middle: you try to reclaim their voices and, above all, how history was born. Sometimes they had the power to change the evolution of history, especially through resistance.

How is history researched from below? Few records of people of low origin.

It's a big challenge. How do you get sources of people who didn't leave documents from their environment? It must be very creative. First, we have to take the documents generated by the elites and read them in the opposite direction between lines, so that sometimes the creators of these documents explain secrets that they did not want to explain. If you want to make history from below, you need to understand how society did documentation about the poor.

"The Caribbean and Brazilian sugar plantations were almost unimaginable scenarios of this, causing people to work to death, literally."

In The Hydra of the Revolution tells the story of the origin of capitalism from the perspective of the poor. Was there little research on the origin of capitalism from this perspective?

There are many studies about the origin of capitalism, but they tend to exclude the people who built capitalism. If you look at economic history, you can think that goods move by themselves throughout the world, that there's no labor -- that vast, bloody project that we showed in the book Peter Linebaugh and I -- the construction of new global capitalism -- looked from the point of view of Hercules, from the point of view of the hydra that each time cut off their minds:

We realized that sailors, slaves, commoners of all kinds, workers, temporary mozos, traders, prostitutes -- ultimately, the poorest -- were fundamental to the great drama of building capitalism. And they kept it. This is very important: they did not blindly follow the higher orders, defended themselves, fought. Insurrections, uprisings -- sometimes even some revolution.

The multi-stranded hydra, fought by Hercules, is the mythological image that Francis Bacon and other authors used in the 17th century to demonize the rebels. Why do you think they chose this figure?

It is more important to choose the figure of Hercules, the figure of great power. Hercules' twelve works to achieve immortality. So the powerful saw themselves as Hercules. "We have a huge job to build a new economic system. And who gets on our way? Who makes it difficult for us to achieve this? they said. They continually use the old myth to describe their project.

Each head of hydra represents a social group that power considers dangerous.

For us, the main heads of the Hydra were, above all, enslaved Africans, whose workforce was transported from West Africa to American plantations through human trafficking. His work spurred the global capitalist economy over two centuries. They are the main head of the Hydra.

Another leader, almost of the same importance, is the sailors. They are decisive because they move a lot and develop their own resistance. The third group is commoners, ordinary people working on communal lands. And we're not just talking about Europe: a lot of people believe that common heritage only existed in Europe, but in West Africa, there were also commoners cultivating communal lands. One of the historic projects of capitalism has been to take these people out of the communal lands to expropriate them: they were driven out by the fences and became the first salaried proletars.

Is it possible to give the hydra another name?

We replace the working class with the term "proletariotza", which we use in the Roman sense of the term. In ancient Rome, the proletarian was the one who did not have the lowest social class; in particular, they referred to women who, by reproducing soldiers, would serve the State. We wanted to make a portrait of the working world, both wage and non-wage. This would include women, but also slaves, who are often left out of the history of work because they did not work for a salary.

In the history of work there is often talk of working white class. But what was the proletarian like?

Over the past 300 years, almost every story is written from a national point of view, and most extol the achievements. Sailors rarely enter national narratives, they are considered marginal. When I started researching sailors, I found that many of them were not part of the history of work, because they didn't produce goods and work outside the national sphere. But they are fundamental to the global capitalist system!

In the 19th century, along with industrialization, we have the history of the working class, which means that we don't see other people outside this field. In a sense, our goal is to create a new definition of the workforce and to show that the history of work is older than we thought. This Atlantic proletarianization invented many things that are part of our modernity, such as strike.

How was that?

In 1768, London sailors reduced their wages. What are you going to do? They approach the boats and they receive candles to prevent them from going out. In English, in the marine language, receiving a candle, it's called to strike, touching the candle. Containers do not move. Capital does not accumulate. And the working class becomes a new kind of power. This marine proletariat is also the creator of the red flag, a symbol of socialist and communist movements around the world. What if I raised the red flag in the middle of a battle? I wanted to say, "We're not going to give up, we're going to fight to death." Pirates made it one of their flags and European workers’ movements ended up being a symbol.

And slave labor is also part of that proletariat.

Its pillar is that sugar was one of the fundamental products of world history. Sugar plantations in the Caribbean and Brazil were almost unimaginable scenarios of this, making people work to death literally. Abolitionists came up with the slogan: "Sugar is made with blood," with blood from African workers.

"They did not blindly follow the higher orders, defended themselves, fought. Rebellions, uprisings..."

We are used to the romantic image of pirates, rebels and villains. But in Villanos of all nations he has made a political interpretation.

The capture of thousands of ships in the golden age of piracy caused a crisis in world trade. One of the things that cut was the slave trade. Many ordinary sailors became pirates and crossed a line, knew they had a lot of chances of being hanged if they were caught. I wondered why they were willing? The life of ordinary sailors was very harsh, with bad food, low wages, very violent captains… Many would say, "Let's live in freedom, even temporarily." They had a phrase to describe it: "A happy, short life."

The pirates created a global crisis and the dominators started a campaign of extermination of the pirates, they squeezed hundreds. They hung their chain bodies, and the crows stung their eyeballs. They were putting themselves in the port's entrance so that any sailor could see it: "This is what we do with pirates. Here's what we're going to do with you. We are merciless." And they were ruthless. There is a war around piracy and class is a kind of war.

He also says that they fought for another social order. How would you describe this order?

They did something completely different: they democratically elected the captain; they also created articles or rules of the boat, a small constitution; they created the checkpoint – the most trusted member of the crew –, was the village rostrum and guarded the captain to ensure that he did not surpass the authority entrusted to him; furthermore, they retained the right to dismiss the captain… At the same time they shared the treasure among all and created a system of social security.

"The pirates created a global crisis and the dominators started a campaign of extermination of the pirates, with hundreds hanged."

Where did you learn that?

They had studied on the bottom deck of the boats they were working on. In other words, these democratic and egalitarian tendencies were always there, but they were crushed by power. Once they had the ability to organize their own boat, these ideas emerged.

He has written about the influence of the Haitian revolution on slavery and piracy. How did this change the world, at least in the Atlantic?

I believe that the Haitian revolution was the beginning of the end of slavery. The revolution gave hope to defeat enslaved people throughout the Western Hemisphere. But that didn't mean it was easy to do. But there was hope, people could see that that situation could end. And it's a shame that history books put aside this fact, people have only talked about the French Revolution. The Haitian revolution was much more radical and in some respects much more significant.

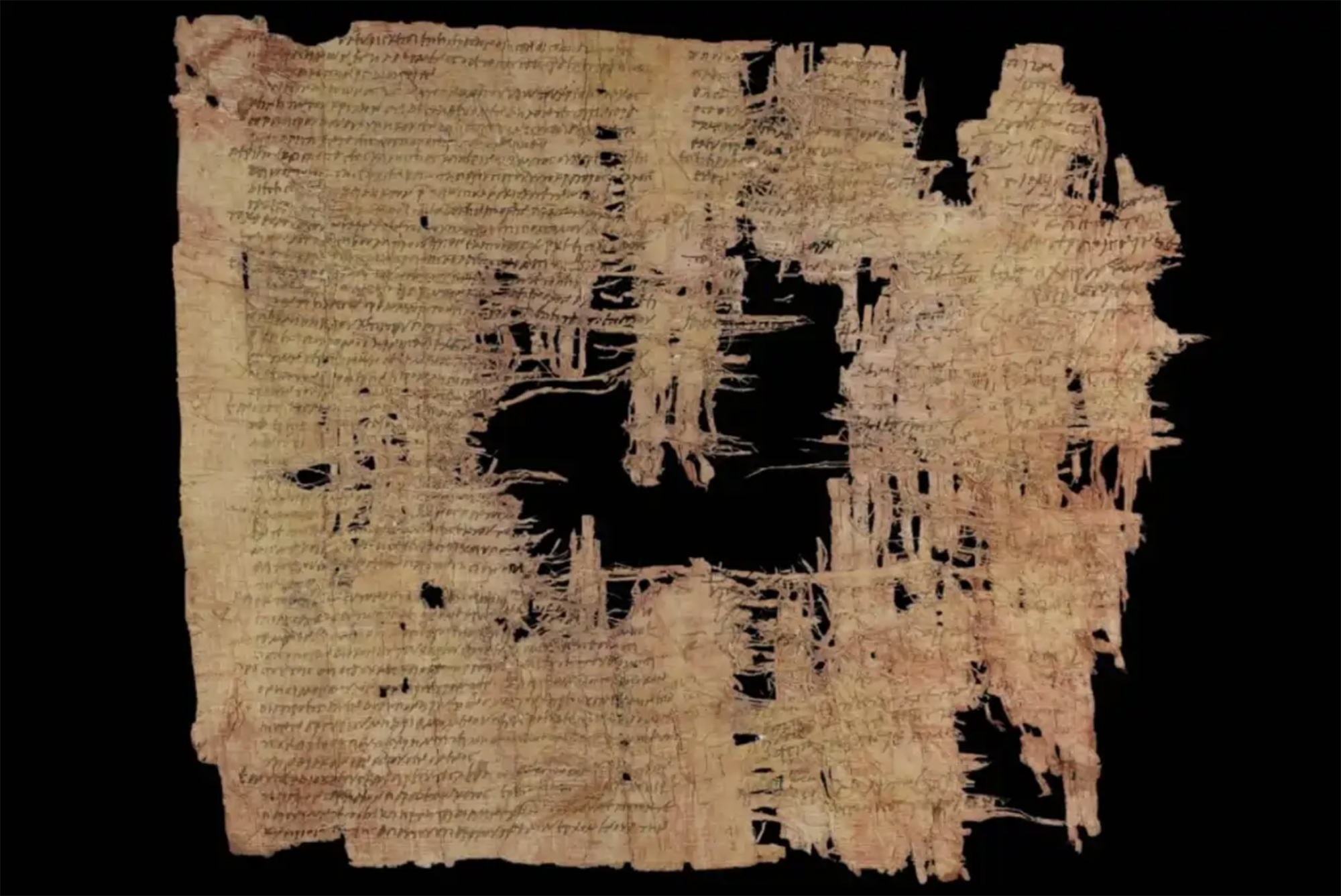

Judea, 2nd century AD. In the turbulent atmosphere of the Roman province, a trial was held against Gaddaliah and Saul, accused of fraud and tax evasion. The trial was reported on a 133-line paper in Greek (pictured). Thinking that it was a Nabataean document, the papyrus was... [+]

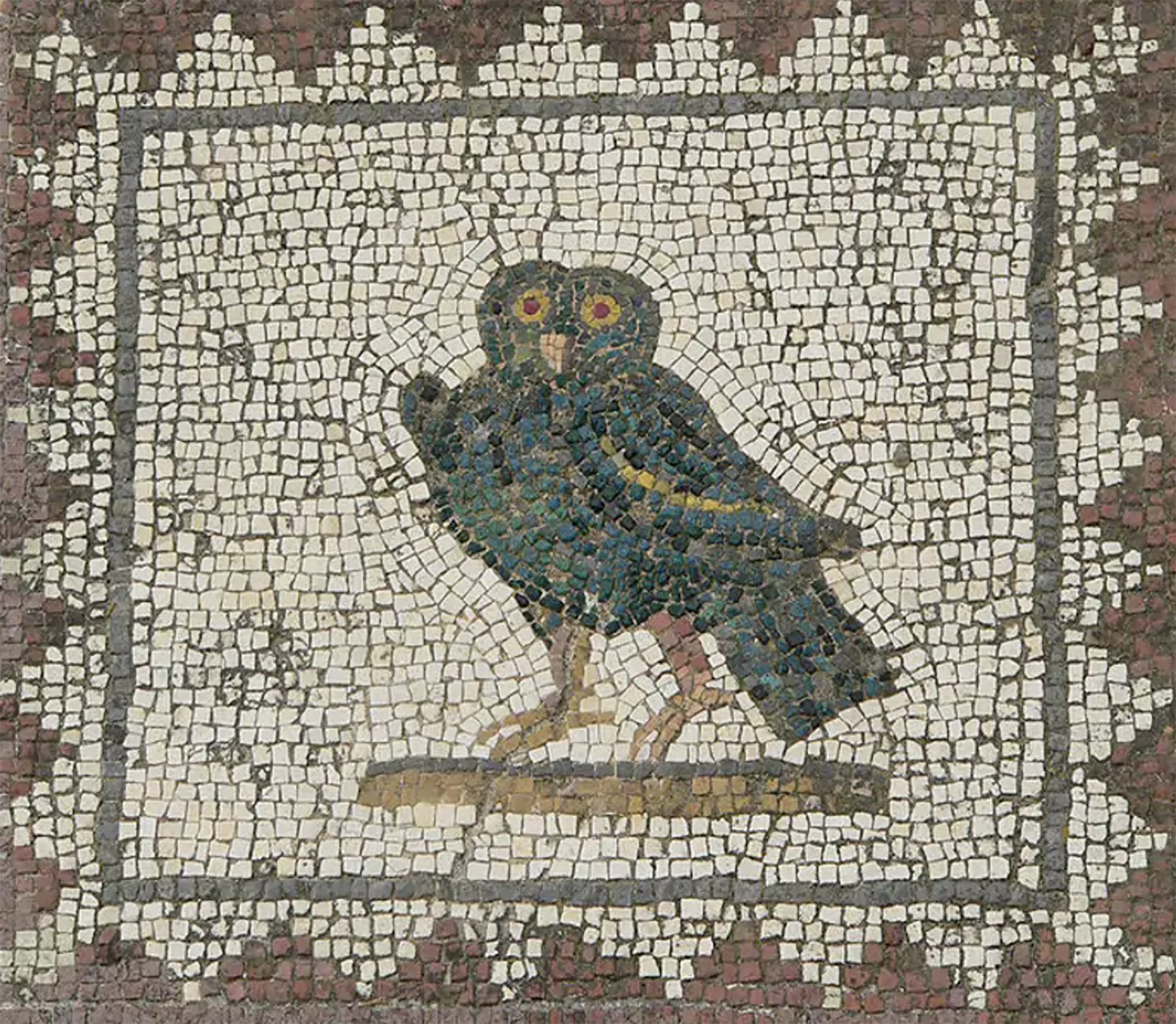

Poloniar ikerlari talde batek Sevillako Italica aztarnategiko Txorien Etxea aztertu du, eta eraikinaren zoruko mosaikoak erromatar garaiko hegazti-bilduma xeheena dela ondorioztatu du.

Txorien etxean 33 hegazti daude mosaikoetan xehetasun handiz irudikatuta. Beste... [+]

Archaeologists have discovered more than 600 engraved stones at the Vasagård site in Denmark. According to the results of the data, dating back to 4,900 years ago, it is also known that a violent eruption of a volcano occurred in Alaska at that time. The effects of this... [+]

Vietnam, February 7, 1965. The U.S. Air Force first used napalma against the civilian population. It was not the first time that gelatinous gasoline was used. It began to be launched with bombs during World War II and, in Vietnam itself, it was used during the Indochina War in... [+]

I just saw a series from another sad detective. All the plots take place on a remote island in Scotland. You know how these fictions work: many dead, ordinary people but not so many, and the dark green landscape. This time it reminded me of a trip I made to the Scottish... [+]

Japan, 8th century. In the middle of the Nara Era they began to use the term furoshiki, but until the Edo Era (XVII-XIX. the 20th century) did not spread. Furoshiki is the art of collecting objects in ovens, but its etymology makes its origin clear: furo means bath and shiki... [+]