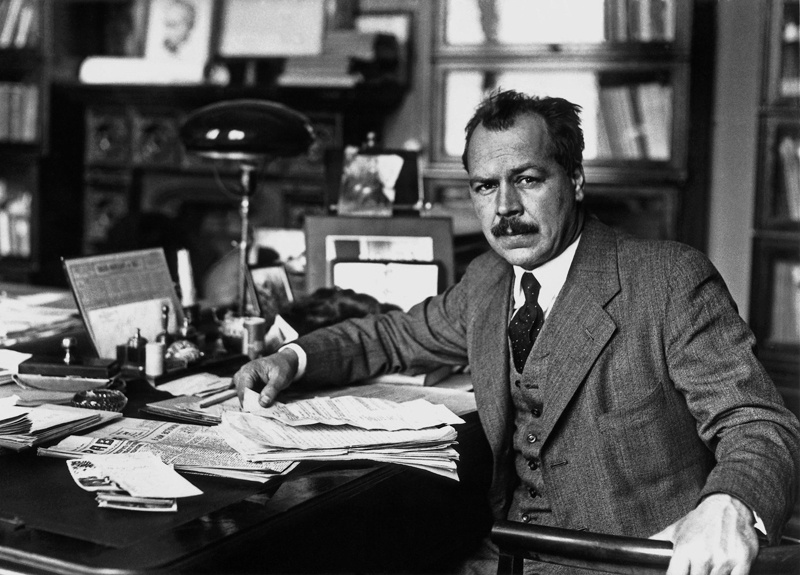

- Nikolaï Ivanovich Vavilov, born in Moscow on 25 November 1887. Botanist and geneticist identified the origin of various cultivated foods. In 1940, when she was collecting seeds on Ukrainian lands, the secret police arrested her and in 1942 she was imprisoned in a cloak. ==Death==On 26 January 1943, Saratov prison died of malnutrition. Why was he arrested? Even, what is its relationship with apple trees?

Before 1887, even in later years, crops were frequently lost in the Russian Empire and the country suffered several famines. Nikolaï Ivanovich Vavilov, with the aim of combating hunger, launched a food cultivation plan that would be able to study botany, genetics and survive in precarious conditions. The first step would be to collect seeds from cultivated plants and their wild ancestors. Where do we start?

Convinced of the importance of genetic diversity, Vavilov was clear that man had to go to the places where man started domesticating plants if he wanted to rescue them. For thousands and thousands of years, farmers were selecting species of high yield and sweet taste, a process in which genes with other properties such as disease resistance and sudden climate change were lost. So it was important for him to find forest ancestors of crops to recover genes lost by domesticated trees.

It identified eight “areas of origin”, grouped by different plant species: Central America, South America, the Mediterranean, the Middle East, Ethiopia, Central Asia, Indo-Malaysian Ecotone and China. In Central America there are sweet potatoes and tomatoes, among others; in South America potatoes, tobacco, rubber; in the Mediterranean, olives, lettuce, hops... At a time when the terms “gene” and “genetics” were not yet sufficiently known, Vavílov developed his plan from the work of Gregor Mendel, “father of genetics”. Some authorities looked at him with suspicion.

Black list of Stalin

In the early years of the 1917 Revolution, Vladimir Lenin, head of the Soviet Russian government, aware of the great potential of Vavilov's dream, which could become a world leader in food production, supported his expeditions. And not a few, the botanist organized over 100 trips and came to coordinate the work of about 25,000 people spread around the world. He also created a large seed bank in the former Leningrad, today St. Petersburg, one of the first in the world. But in 1924 Lenin died and his place was occupied by Iosif Stalin, who had a very different genetic view.

Vavilov also took into account the theories of non-Russian scientists, and for Stalin this was enough to go straight into the list of potential conspirators against the government. Not only that, for him Vavílov’s plan was overwhelmingly bourgeois. All this stuff that plants inherit and transfer genes -- no. However, many compatriots at that time appreciated botanist and it would not be easy to face it. Stalin had to wait a bit.

Guilty of hunger

Years earlier, Vavilov invited a young Ukrainian to work with him: Your name was Trofim Lysenko. I didn't even imagine that the kid who was so excited was waiting for him to hurt. When a new famine hit the country, the geneticist was hit.

To a large extent, hunger was the result of decisions taken by Stalin which, among other measures, the farms were collectivized. He therefore had to necessarily find a culprit to conceal his failure. And he finds it. He granted Vavilov a period of three years to create varieties resistant to anything, although the botanist had already said it would take at least ten years. Meanwhile, Lysenko, a young worker who would become an agronomist, protected by senior officials, launched a pseudo-scientific campaign against genetics theories.

Lysen and his followers believe that to change the characteristics inherited by a plant it was enough to plant it in a place with different external conditions. For example, they said maize would grow faster in the northern part, where it's colder. “Vavilov is reactionary, bourgeois, idealistic and formalist,” Lysenko said. In a few years, Vavilov was politically and academically rejected. It was prohibited from attending international seminars and was only allowed to carry out expeditions to nearby countries such as Crimea and Ukraine. In 1940, accused of espionage, he was imprisoned by the secret police.

Seed defence

In September 1941, Hitler besieged Leningrad. The citizens spent almost 900 days surrounded by the Nazis, with cold and hunger. During the siege, thousands of seeds, roots and fruits from the seed bank of Leningrad remained hidden in a winery, in order to protect themselves from the Nazis, also from the hungry and rat population, because the Soviet authorities did not make any effort to relocate them, as is the case with the works of the Hermitage Museum. The Hiatos were monitored alternately by their Vavilov companions, some of whom died before they ate what they had hidden, because they preferred to keep seeds for the generations they would need after the war, according to ethnologist Gary Paul Nabhan. Among those who managed to survive was the Kazakh pomologist Aymak Djangalievich Djangaliev (1913-2009), another great protagonist of this story. In collaboration with Vavilov, he discovered the origin of the domestic apple (malus domestica) in the wild apple (malus sieversii) of the forests of Kazakhstan, as confirmed by subsequent studies. Vavilov and Djangaliev discovered that the “cradle” of the apple is located in the Tian Shan Mountain, on the border between Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and China. Anyone who wants to know more about the topic can read the report we published two years ago in Sagarrondo magazine: Tian Shan Saw, "cradle" of apples.

Until the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989 and the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991, the works of the botanists Vavilov and Djangaliev were unknown in the West. For many years, Djangaliev, in the largest city of Kazakhstan, secretly continued his investigations in Almaty, which means in his original language “the father of the apple”.

In 2010, shortly after the death of Djangaliev, film director Catherine Peix created the documentary Les Origines de la pomme, based on the story of the journalist scientist. Last December 1, the Erribera de Astigarraga Cultural Center took place the Peix Day, Sagardo Forum, organized by the Territory of the Sidra.En Kazakhstan, the origin of the apple cultivated in the talk, talked about the resistance of the apples malus sieversii to diseases and the importance of protecting the biodiversity of the forests in times when deforestation is so severe.

Second place

But the story goes on. Twelve years ago, a construction company expressed its desire to demolish the Pavlovsk Experimental Station, where the Vavilov seed collection is preserved, and to build houses where it is located, among other things because the collection that gathers 1,000 strawberries, 1,200 maize species and 1,000 apple species "is worth nothing". However, a number of international experts called for the project to be halted and former President Dmitri Medvedev accepted the revised conditions. So far, President Vladimir Putin has not responded to the project. This case has been called "second place" in Russia.