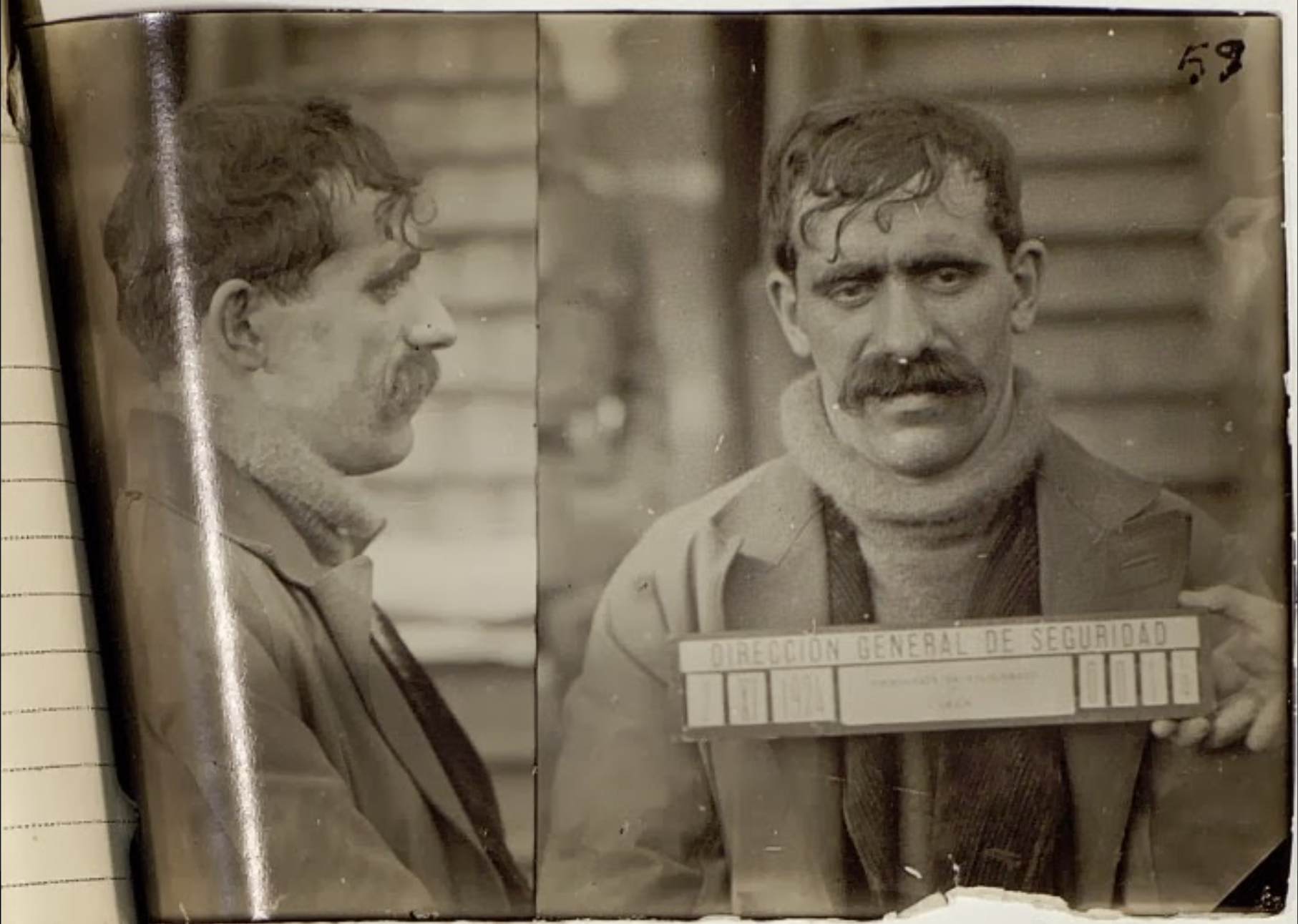

Shadow of archaeologists in the shade

Errenteria (Gipuzkoa), 1892. In the caves of Aizpitarte the first archaeological excavations of Gipuzkoa were carried out, at the hand of the group led by Count Lersundi. Eleven years later, in 1903, the king of Spain, Alfonso XIII, visited the site and with this excuse photographed the working group; in the photo we see that there were women in the group, although their names have not come to us.

This photograph starts the exhibition Women Archaeologists in Gipuzkoa, which can be visited at the Oiasso de Irun museum until the end of March next year.

The first name is Maria Luisa Aranzadi. Telesforo was familiar to Aranzadi and appears in a photograph made in Aralar in 1917. That same year Telesforo, José Miguel de Barandiarán and Enrique Eguren began one of the brightest stages of Gipuzkoan archaeology. And in the shadow of that brilliance there was also a woman.

The Society of Sciences Aranzadi was born 30 years later and was fundamental in its foundation Pilar Sansinenea (1905-1997), as well as in the works carried out by her husband Jesús Elosegi to find cromlechs and dolmens.

In the early 1960s, the archaeologist Dolores Echaide (1928-2018) worked on the excavations of Soria, Torralba and Ambrona. The work carried out by the multidisciplinary team was a milestone in European archeology, but Echaide’s work was not deserved recognition.

Also pioneered was the excavation of Lezetxiki (Arrasate), directed by Aita Barandiaran from 1956 to 1968, in which Ana María Muñoz Amilibia, the first archaeologist of the Spanish State, intervened.

After excavations, these shadow works outside the fields lack visibility of the excavation director's position, being often in the hands of women such as palinology, sedimentology, numismatics, osteoarcheology, etc.

Secondary archaeologists

The two excavations carried out in the 1970s show the reasons why the work of archaeologists was in the shadow. In 1972 the investigation began of the Roman necropolis of Nuestra Señora de Xantalén, in Irún. Women were the majority in this group, with Pilar Utrilla, Ana Cava and Teresa Andrés, among others.

But then, in archaeology, prehistoric excavations were considered of the first order and historical research, such as those of the Roman era, was considered of the second category, in which women acted mostly. In addition, the head of the excavation of Ama Xantalen was a man: Ignacio Barandiaran. In 1979 the excavation from the cave of Amalda in Zestoa was also directed by a man: Jesus Altuna.

The group included several women who were responsible for recording the Amelia Baldeon and Koro Mariezkurra materials. After excavations, these jobs in the shadow outside the fields do not have the spectacularity of the excavation director's position, and they have often been in the hands of women: palinology, sedimentology, numismatics, osteoarcheology… And this reality is not only limited to Gipuzkoa, but all these examples also reflect the situation outside Gipuzkoa.

In the case of Gipuzkoa, the change began 40 years ago. In 1983 the Society of Sciences Aranzadi launched the archeology department, in which several women participated. And the following year, in 1984, Mertxe Urteaga directed the excavations of the cave of Iruaxpe III; in Gipuzkoa a a woman first received authorization to lead an excavation.

From that moment on, the exhibition collects the names of dozens of women archaeologists. But this doesn't mean that they didn't dedicate themselves to archaeology before, but that their fundamental work began to be seen little by little from then on.

Tennessee (United States), 1820. The slave Nathan Green is born, known as Nearest Uncle or Nearest Uncle. We do not know exactly when he was born and, in general, we have very little data about him until 1863, when he achieved emancipation. We know that in the late 1850s Dan... [+]

New York, 1960. At a UN meeting, Nigeria’s Foreign Minister and UN ambassador Jaja Wachucu slept. Nigeria had just achieved independence on 1 October. Therefore, Wachuku became the first UN representative in Nigeria and had just taken office.

In contradiction to the... [+]

Researchers at Johns Hopkins University have discovered several cylinders with inscriptions at the present Syrian Reservoir, the Tell Umm-el Marra. Experts believe that the signs written in these pieces of clay can be alphabetical.

In the 15th century a. The cylinders have... [+]

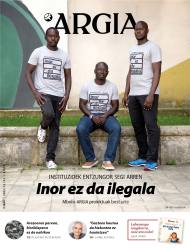

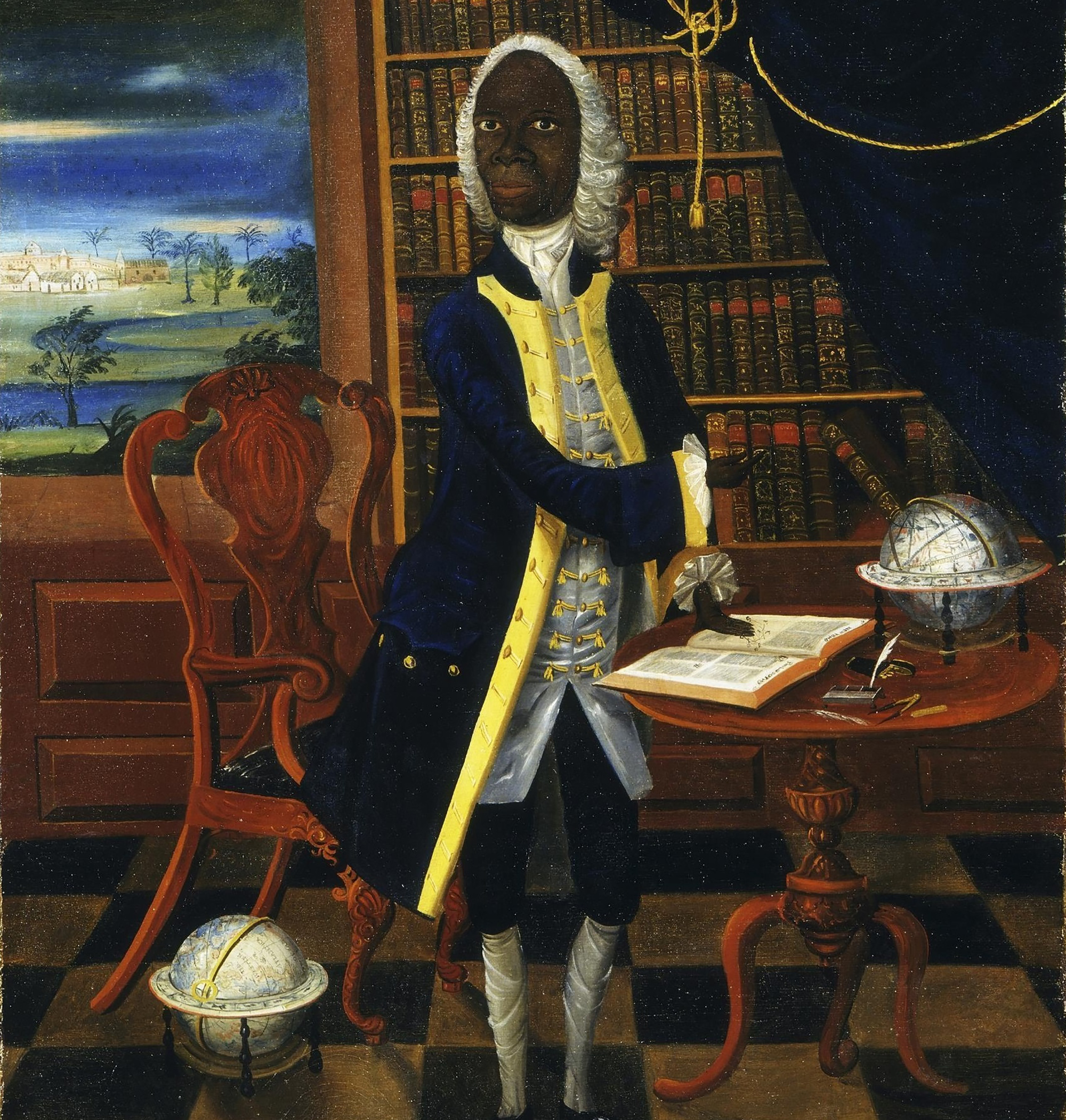

London 1928. At the Victoria and Albert Museum there was a very special painting: in the painting there is a black man, with wig and Levite, surrounded by books and scientific instruments. Thus it was catalogued in the Museum: “Unique satirical portrait representing a failed... [+]

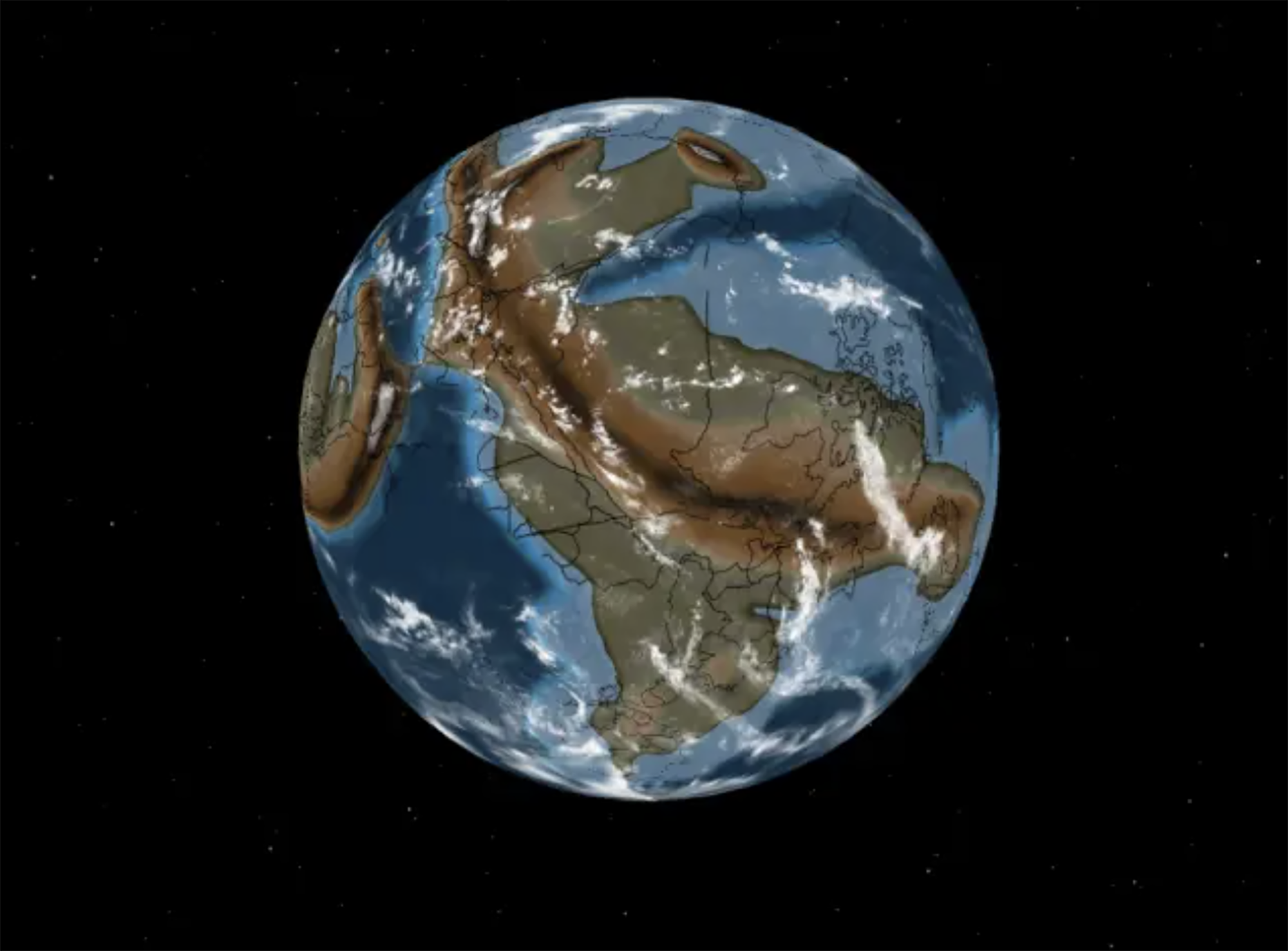

Ethiopia, 24 November 1974. Lucy's skeleton was found in Hadar, one of the oldest traces of human ancestors. The Australian hominid of Australopithecus afarensis is between 3.2 and 3.5 million years old.

So they considered it the ancestor of species, the mother of all of us. In... [+]

A group of archaeologists from the University of Berkeley, California, USA. That is, men didn't launch the lances to hunt mammoths and other great mammals. That was the most widespread hypothesis so far, the technique we've seen in movies, video games ...

But the study, published... [+]

Zamora, late 10th century. On the banks of the Douro River and outside the city walls the church of Santiago de los Caballeros was built. The inside capitals of the church depict varied scenes with sexual content: an orgy, a naked woman holding the penis of a man… in the... [+]

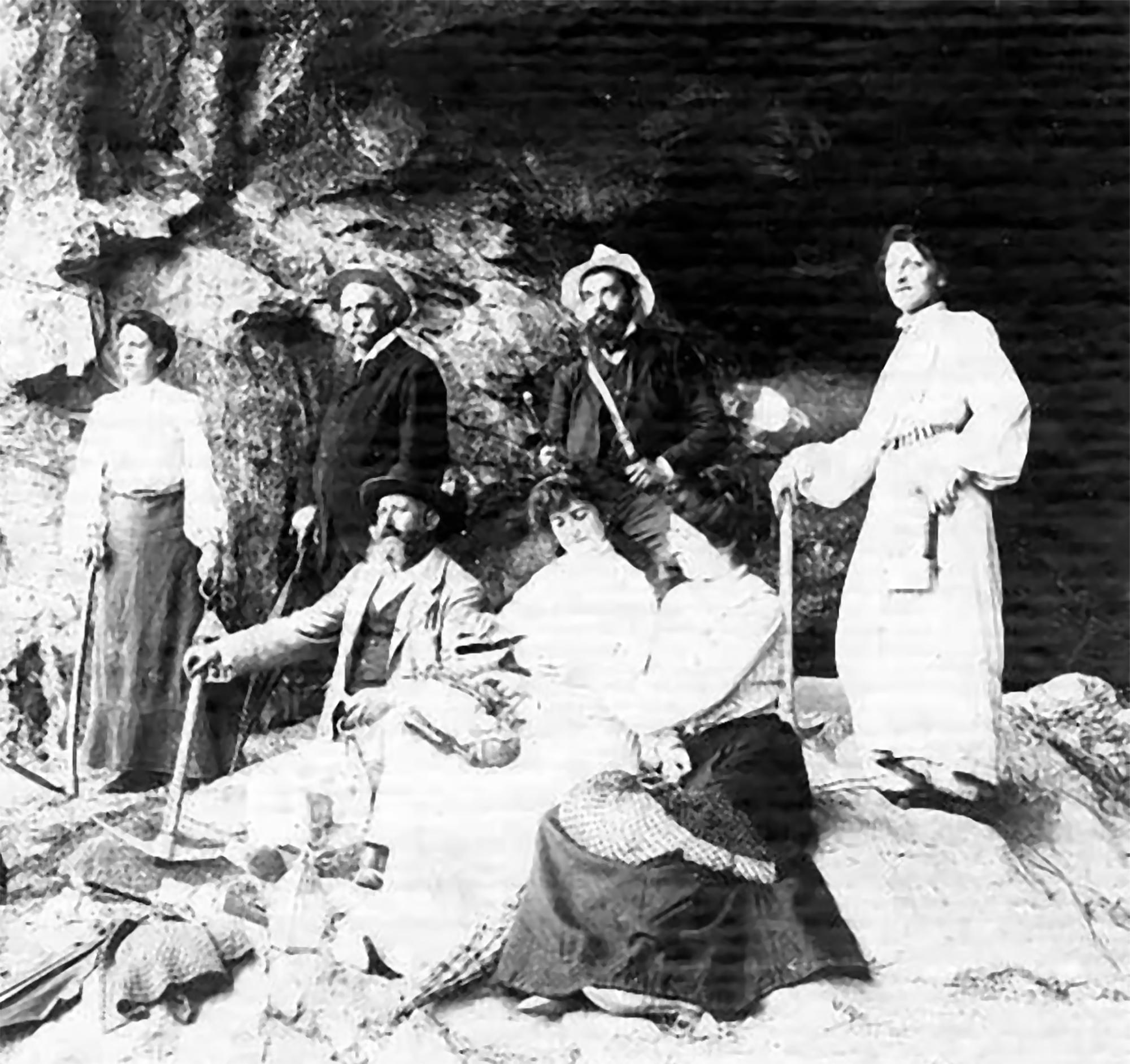

Born 7 November 1924. A group of anarchists broke into Bera this morning to protest against the dictatorship of Primo de Rivera and to begin the revolution in the Spanish state.

Last October, the composition of the Central Board was announced between the displaced from Spain... [+]

Washington (EE.UU. ), 1807. The US Constitution banned transatlantic slave trade. This does not mean that slavery has been abolished, but that the main source of the slaves has been interrupted. Thus, slave women became the only way to “produce” new slaves.

So in 1845, in... [+]

A group of interdisciplinary researchers from the Free University of Berlin and the Zuse Institute have developed a complex mathematical model to better understand how Romanization spread in North Africa.

According to a study published in the journal Plos One, the model has... [+]

While working at a site in the Roman era of Normandy, several archaeology students have recently made a curious discovery: inside a clay pot they found a small glass jar, of which women used to bring perfume in the 19th century.

And inside the jar was a little papelite with a... [+]

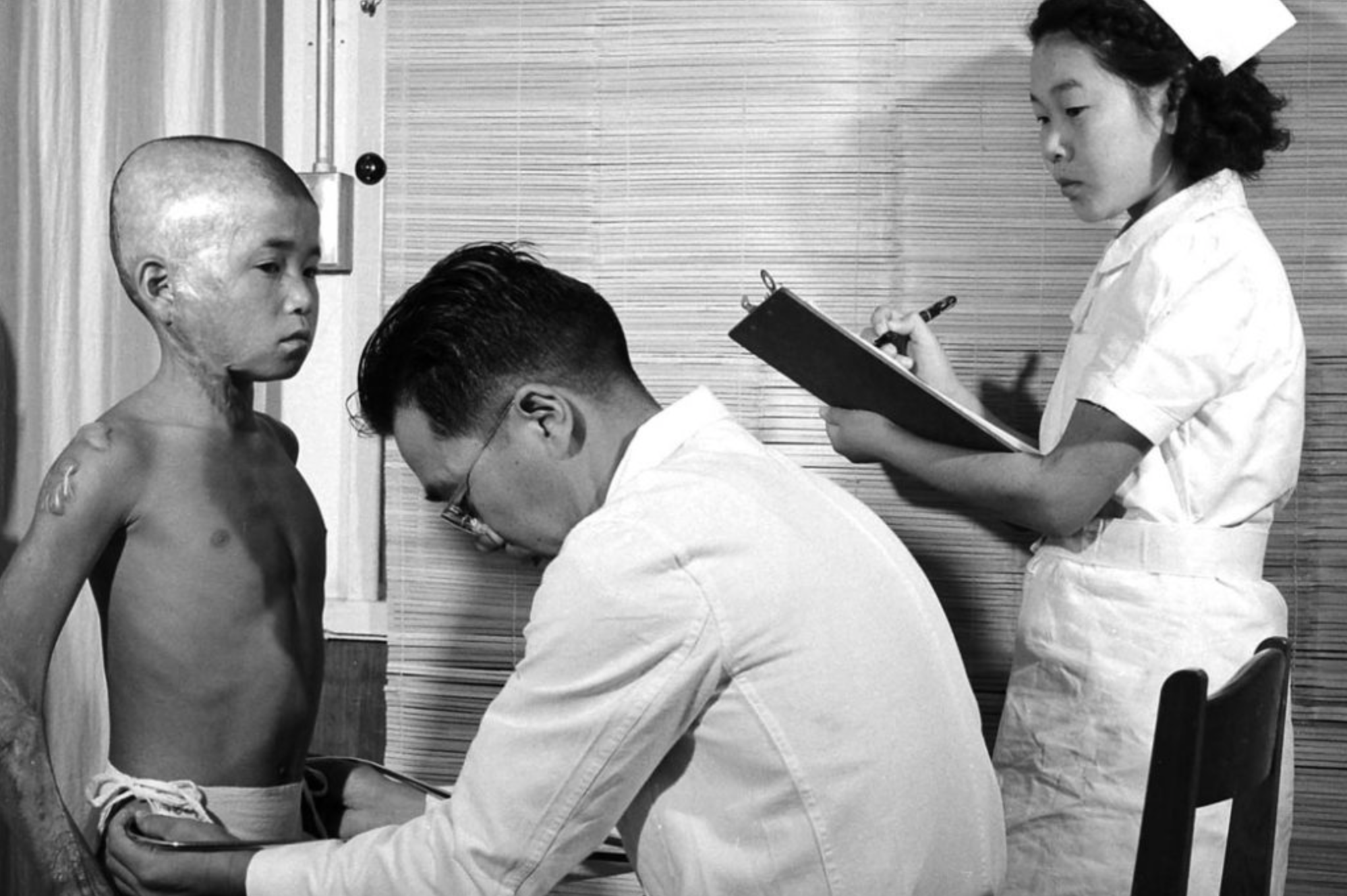

Japan, 6 and 9 August 1945, the United States launched an atomic bomb causing tens of thousands of deaths in Hiroshima and Nagasaki; although there are no precise figures, the most cautious estimates indicate that at least 210,000 people died at the end of that year. But in... [+]

A team of researchers led by the Japanese archaeologist Masato Sakai of the University of Yamagata has discovered numerous geoglyphs in the Nazca Desert (Peru). In total, 303 geoglyphs have been found, almost twice as many geoglyphs as previously known. To do so, researchers... [+]

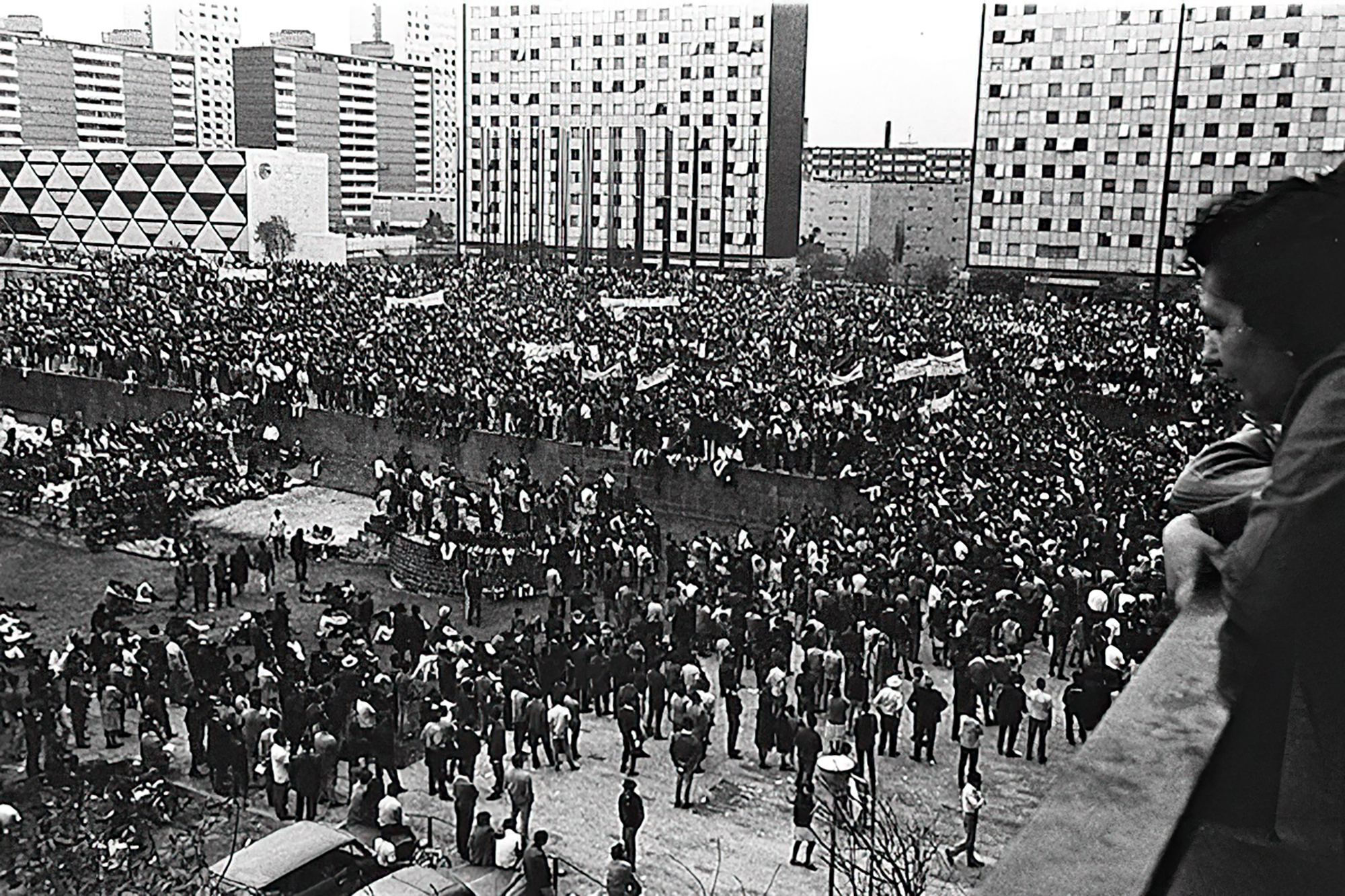

Born 2 October 1968. A few months earlier, the student movement started on June 22 organized a rally in the Plaza de las Tres Cultura, in the Nonoalco-Tlatelolco unit of the city. The students gathered by the Mexican army and the paramilitary group Olympia Battalion were... [+]