How are we going to remember Intxaurrondo?

- The construction of a new Civil Guard headquarters in San Sebastian is planned at the end of this 1970s. But because they had difficulty obtaining building licenses, the government of the UCD of Madrid decided to buy a block for workers. Intxaurrondo Headquarters or Command 513 became operational in 1980

San Sebastián, 1968. The City Hall approved the urban planning of the Intxaurrondo district, with the consequent demolition of 19 villages. In the mid-1950s, working-class neighborhoods began to be built in disorderly fashion and by speculation. However, after the demolition of the dwellings, in the 1970s the urbanization began to take place in a more planned way, and gradually the old rural space was occupied with housing blocks.

At the end of this decade, the construction of a new Civil Guard headquarters in San Sebastian is planned. But because they had difficulty obtaining building licenses, the government of the UCD of Madrid decided to buy a block for workers. The Intxaurrondo headquarters or Command 513 came into operation in 1980, led by Commander Enrique Rodríguez Galindo (1939-2021). At first, until the expansion of the neighborhood was completed, the barracks were isolated and soon extreme security measures made it strong, even the nickname

Fort Apache. For some Intxaurrondo is a symbol of the fight against ETA, from which 278 commands were deactivated and 1,550 members of the organization were arrested.

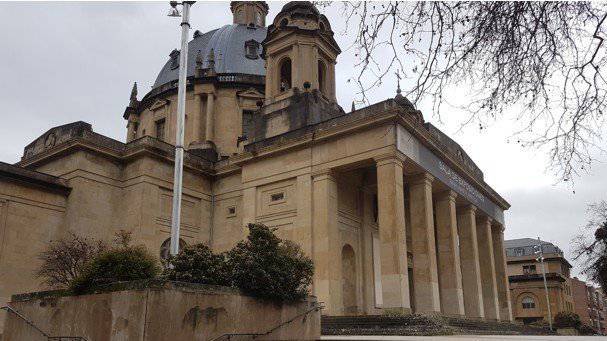

Throughout the world, several buildings that had been torture spaces are becoming memory spaces (...) But the main torture centre in Western Europe remains the seat of the Command of the Civil Guard of Gipuzkoa

But those who rely on the torture allegations of hundreds and hundreds have given the headquarters other titles: “The Torture Laboratory,” “the main torture centre in Western Europe.” The first case of torture related to the Intxaurrondo headquarters was prior to the inauguration of the headquarters. During the construction of the administrative headquarters, ETA triggered a bomb explosion and arrested Mikel Amilibia. Despite his release without evidence, lawyer Juan Mari Bandres denounced the torture of Amilibia. And not only did the detainees or their lawyers report torture. Amnesty International first reported two cases of torture in Intxaurrondo in 1984.

Around the world, several buildings that had been torture spaces are becoming spaces of memory. Villa Grimaldi, a former detention and torture centre during the Pinochet era in Chile, has become a Peace Museum. In the Santiago stadium, dozens of people were tortured and killed in 1973, including Victor Jara, and since 2003 the stadium has been named the poet and singer. In Barcelona, steps have been taken to turn the police headquarters of Via Laietana into “a place of memory of democracy” so that the systematic torture of Franco’s regime is not forgotten. In the same city of San Sebastian last year, an agreement was signed with the Spanish Government to make the La Cumbre Palace available to the City Hall and make it a memory space. Lasa and Zabala were tortured at the Summit and at the Intxaurrondo headquarters. But the main torture centre in Western Europe remains the seat of the Command of the Civil Guard of Gipuzkoa.

Urruña, 1750eko martxoaren 1a. Herriko hainbat emakumek kaleak hartu zituzten Frantziako Gobernuak ezarritako tabakoaren gaineko zergaren aurka protesta egiteko. Gobernuak matxinada itzaltzeko armada bidaltzea erabaki zuen, zehazki, Arloneko destakamentu bat. Militarrek... [+]

Ezpatak, labanak, kaskoak, fusilak, pistolak, kanoiak, munizioak, lehergailuak, uniformeak, armadurak, ezkutuak, babesak, zaldunak, hegazkinak eta tankeak. Han eta hemen, bada jende klase bat historia militarrarekin liluratuta dagoena. Gehien-gehienak, historia-zaleak izaten... [+]

In the Maszycka cave in Poland, remains of 18,000 years ago were found at the end of the 19th century. But recently, human bones have been studied using new technologies and found clear signs of cannibalism.

This is not the first time that a study has reached this conclusion,... [+]

Porzheim, Germany, February 23, 1945. About eight o’clock in the evening, Allied planes began bombing the city with incendiary bombs. The attack caused a terrible massacre in a short time. But what happened in Pforzheim was overshadowed by the Allied bombing of Dresden a few... [+]

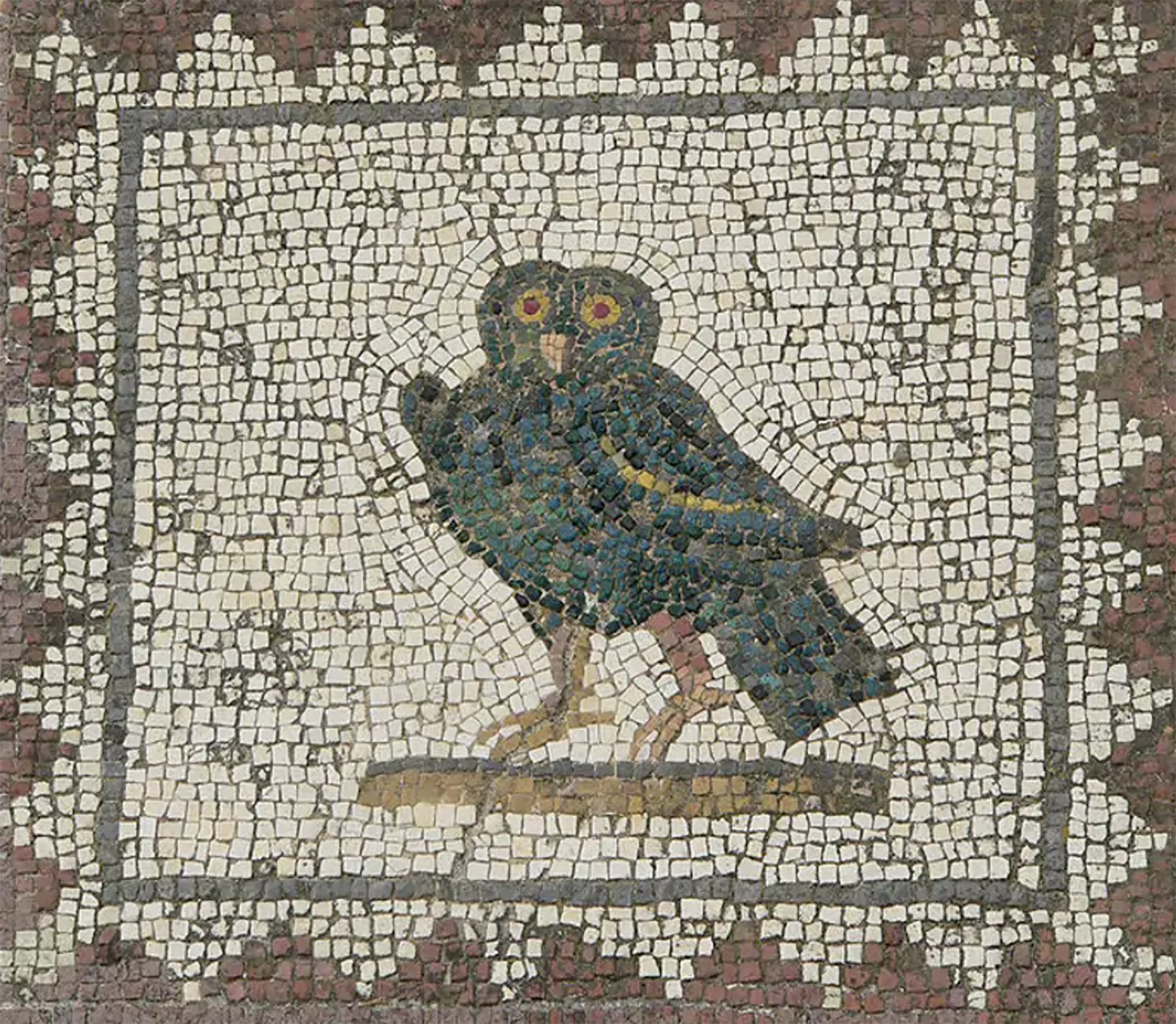

Poloniar ikerlari talde batek Sevillako Italica aztarnategiko Txorien Etxea aztertu du, eta eraikinaren zoruko mosaikoak erromatar garaiko hegazti-bilduma xeheena dela ondorioztatu du.

Txorien etxean 33 hegazti daude mosaikoetan xehetasun handiz irudikatuta. Beste... [+]

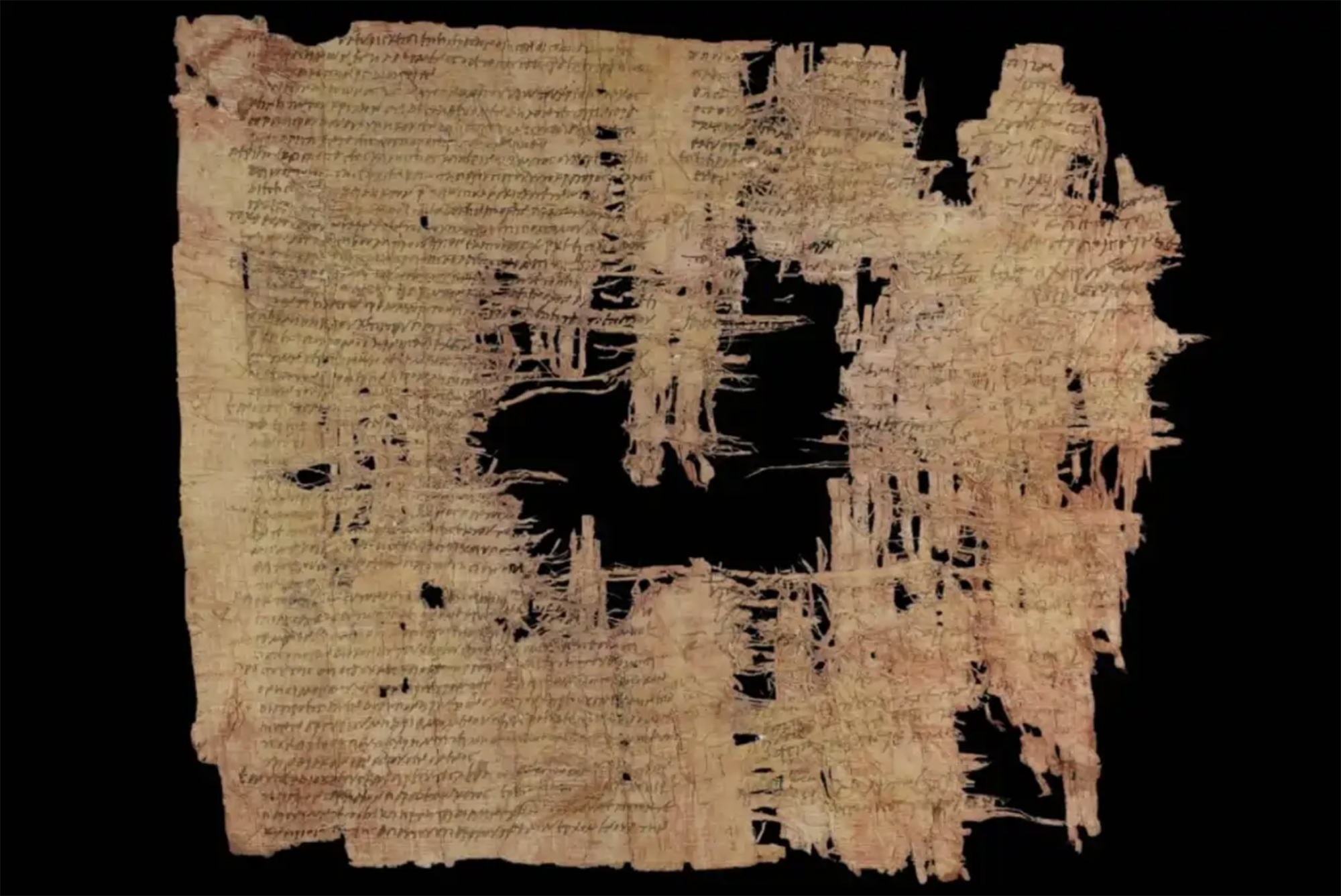

Judea, 2nd century AD. In the turbulent atmosphere of the Roman province, a trial was held against Gaddaliah and Saul, accused of fraud and tax evasion. The trial was reported on a 133-line paper in Greek (pictured). Thinking that it was a Nabataean document, the papyrus was... [+]

Vietnam, February 7, 1965. The U.S. Air Force first used napalma against the civilian population. It was not the first time that gelatinous gasoline was used. It began to be launched with bombs during World War II and, in Vietnam itself, it was used during the Indochina War in... [+]