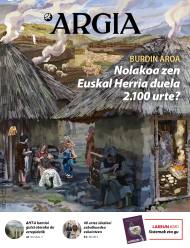

A journey through the Basque Country of protohistory

- The public presentation of the hand of Irulegi has aroused in society the interest to know what the Basque Country was like over two thousand years ago. Fortunately, the archaeology of the Iron Age has a long tradition in our country, and knowing some of the sites of the time, we propose here a small trip to the past through the Basque territories.

Research on protohistory, as in other fields, began in the early 20th century in the Basque Country with the group formed by Telesforo Aranzadi, Joxemiel Barandiaran and Enrike Eguren in 1916. The first works mainly focused on the identification and cataloging of megalithic monuments, but were interrupted by the War of 1936. In the following decades, however, the investigations were gradually recovering, and in

1957 Barandiarán ran the first excavation program in a fortified town of the Iron Age, called Intxur, in Albiztur. This type of work increased considerably from the 1970s and, above all, from 1980, by the creation and impulse of new researchers and groups.

As a result, today we have a rich cultural heritage of the final stages of the Iron Age. Many sites have been excavated, the structure and way of life of its inhabitants can be rebuilt and the influence of Romanization is increasingly known. Let's get some examples.

.jpg) Irulegi, much more than the hand

Irulegi, much more than the hand

The fortified town of Irulegi, located in Lakidain, is probably the most significant site in recent times. The Society of Sciences Aranzadi has been working since 2007 in cooperation with the City of Aranguren. Since 2018 the archaeologist Mattin Aiestaran has taken over the direction of the works.

The site is located at the top of the mountain of the same name, almost 900 meters high. Signs of human occupation start from the Bronze Age, to C. XIV-XII. in the centuries. Since then, researchers have found remains of several overlapping phases, witnesses of a history of over a thousand years. However, at the end of the Iron Age the urban core had its flowering, a. C. Between the fourth and first centuries. At this time, Irulegi became almost urban in nature: at the top of the mountain there was an acropolis or fortress surrounded by Lubanos, with residential settlements located on the slopes surrounding it. Both geophysical explorations and excavations have allowed archaeologists to identify the drawings of some houses organized around a street, in the ruins of one of them appeared the bronze hand that has shaken the history of the Basque country. Around this town was built a monumental wall surrounding the entire mountain, closing an area of approximately 12 hectares, and researchers believe that within this oppidum there were not only inhabited nuclei but also growing areas.

Situated in the Basque territory, the war in Sertorio seriously affected Irulegi. It is not yet clear on which side the vascones slipped. It is clear, however, that they were attacked by a Roman army. By the year 75, the people were completely burned and their inhabitants fled, leaving behind all their property. After the attack, the Roman city of Pamplona began to develop a few kilometres from there, and the village of Irulegi was forgotten until the arrival of archaeologists.

.jpg)

War echoes from the Ebro to the Pyrenees

The destruction of Irulegi was not an isolated event. There are many archaeological findings that have demonstrated the influence of the Sertorio War in the current Basque Country. South-west, the fortified town of La Guardia in Viana is another significant example.

Directed by Javier Armendariz, it has a team of researchers from the Public University of Navarra. Also in this case, it was a fortified town of almost urban character, but it is not clear whether it corresponded in antiquity to the territory of the Basques or berons. There are written testimonies that speak of the city of Uarakos, where the berons are first mentioned. This people could be Celtiberian. In fact, archaeologists have found in Viana elements of this cultural area. In this case, there are also signs of a violent attack, including the dead victims on the streets.

More curious is the case of Barkox's treasury. In 1879, Mrs. Ezlucha accidentally discovered a boat with over 1,700 silver denariums buried in a nearby land. She studied the expert in numismatic Émile Taillebois and concluded that they were coins from the Ebro area, from the Basque region, sometimes the name of the coin house called Barskunes can also be distinguished. However, there were no Roman coins.

.jpg)

Today it is impossible to know how that treasure came to that corner across the Pyrenees, the present Zuberoa. Given the characteristics of the discovery, it has

been suggested that someone who fled in the context of the Sertorio war would conceal it. On the contrary, for others, it can be proof that their tribes have positioned themselves in favor of Sertorio, since César mentions that the Aquitans received the help of the leaders of the northern Iberian Peninsula, formed with Sertorio. All the hypotheses are then open.

Atalayas of custody of the territory

However, the fortified peoples of the Iron Age have received the attention of archaeologists on the Cantabrian side. The work carried out for decades has allowed many fields of different sizes to emerge. In Gipuzkoa, researchers from the Society of Sciences Aranzadi, in collaboration with the Provincial Council, such as the archaeologists Xabier Peñalver, Carlos Olaetxea and Sonia San José, who have carried out various works in the impressive villages of Intxur (Albiztur), Basain (Anoeta), Buruntza. In Álava, the archaeologist Jon Obaldia of the same association has been in charge in recent years of the investigation of the fortified people of Babio (Izoria, Ayala). In Bizkaia, the Provincial Council and the University of the Basque Country/Euskal Herriko Unibertsitatea have promoted various initiatives for the investigation of fortified peoples such as Berreaga (Mungia), Kosnoaga (Gernika-Lumo) and Arrola (Arratzu).

Among the archaeological studies of the Iron Age, it has become increasingly clear lately that the societies of that time did not live only in fortified villages.

The latter is one of the best preserved. Situated at the top of the mountain of the same name, it has an excellent panorama towards the Ria de Urdaibai and towards Mount Oiz. The last excavations were carried out between 2004 and 2006 under the direction of the archaeologist Mikel Unzueta. The site occupies an area between 8 and 13 hectares, surrounded by strong stone walls, 7-8 meters thick at the base and 5-6 meters high. To the West, archaeologists have excavated a monumental entrance of curves that highlights the fortified character of the town. The houses are attached to the interior of the wall, with rectangular plan and stone base. The walls were built in both wood and pesetas and had straw covers.

A few meters from Arrola is the deposit called Gastiburu, also from the Iron Age. Researched by archaeologist Luis Valdés in the 1980s, he believes they are the remains of a sanctuary. Around a Pentagon square there are five horseshoe structures.

.jpg)

The two sites, Arrola and Gastiburu, are considered to be part of the same complex located in the Caristian territory. The archaeological materials found give an image of a complex society, with diversified agriculture and livestock and exchanges with other peoples. Most structures a. C. IV.-III. They were built in centuries and developed. Until the 1st century. However, at that time the Romanization began to consolidate itself also on the Basque coast, which meant a change in the territorial hierarchies. It is unclear whether Arrola suffered some kind of attack or was slowly being emptied, but, a. C. In the 1st century he seems to have lost centrality for the benefit of the Roman city of Forua.

Beyond the fortified villages

Among the archaeological studies of the Iron Age, it has become increasingly clear lately that the societies of that time did not live only in the fortified villages. On the contrary, there are some discoveries that reflect a model of occupation of the diversified territory, and what is more interesting, some of them seem to have continued in the Romanization era and later. Probably the most interesting example are the excavations carried out in the church of

Santa Maria de Zarautz. The works, directed by archaeologists Alex Ibañez and Nerea Sarasola in the 2000s, yield surprising results: the area has been permanently occupied since the Iron Age and signs of different phases can be observed, even today under the temple floor. The oldest occupation symptom is C. They are the remains of a house built in the 5th century, the first discovered on the shore of the sea and in the midst of a current urban nucleus. It had a rectangular plan and it seems to be made of wood, since no walls were found in the excavations. In one corner of the floor there appeared traces of a low fire, both to warm the building and with a kitchen function. Artisanal ceramic fragments also appeared throughout the area.

.jpg)

A public building of the Roman style appeared on this house, AD. In fact, the port of Zarautz, and a few kilometers from it, also the port of Getaria, became important during the Romanization era, within the commercial network Via Maris, built around the Atlantic Ocean. Thus, some researchers consider that these deposits can be identified with the Bardulian zone of Diaz, which is cited in classical sources, but this hypothesis is not yet confirmed.

Another important site is Santiagomendi. Archaeologist Maite Izquierdo performed several surveys in the 1990s, and more recently he has taken the witness Manu Zeberio, of the Society of Aranzadi Sciences. The site is located on the mountain of the same name, in Astigarraga, with a magnificent view over the Urumea estuary. Researchers have excavated several structures and a great number of ceramics from the Iron Age have appeared, but there are no signs of a wall, so they consider that there was an unfortified residential complex. A.C. V.-I. For centuries it had its greatest development, and perhaps could be identified with the Bardulian oppidum called Morogi, cited in classical sources (the toponym Murgia is still preserved in Astigarraga). Taking advantage of natural shelters, oppidums were fortresses and urbanized spaces closed by man with walls in the hills and plateaus, and they usually controlled the surrounding territory through this location.

In this case of Astigarraga it is observed that the Romanization caused a change of territorial hierarchies: the town of Santiagomendi did not disappear rapidly, but it did. In the first century its importance was gradually diminishing for the benefit of the documented Roman deposits in the Concha Bay area, until they were finally abandoned. As we have seen on this short journey, the harvest of the archaeology of the Iron Age in the Basque Country has

been abundant. Eleven other sites have been researched, and work continues: excavations, topography, analysis and material dating in specialized laboratories, dissemination, etc. Scientific knowledge is the result of the collaboration between researchers, local agents and initiatives, educational institutions and administrations, and the commitment of all is essential to continue completing this small map we have drawn to this day and to better know the life of our ancestors over two thousand years ago.

Ethiopia, 24 November 1974. Lucy's skeleton was found in Hadar, one of the oldest traces of human ancestors. The Australian hominid of Australopithecus afarensis is between 3.2 and 3.5 million years old.

So they considered it the ancestor of species, the mother of all of us. In... [+]

While working at a site in the Roman era of Normandy, several archaeology students have recently made a curious discovery: inside a clay pot they found a small glass jar, of which women used to bring perfume in the 19th century.

And inside the jar was a little papelite with a... [+]

A team of researchers led by the Japanese archaeologist Masato Sakai of the University of Yamagata has discovered numerous geoglyphs in the Nazca Desert (Peru). In total, 303 geoglyphs have been found, almost twice as many geoglyphs as previously known. To do so, researchers... [+]

Treviño, 6th century. A group of hermits began living in the caves of Las Gobas and excavated new caves in the gorge of the Laño River, occupied since prehistory. In the next century, the community began to use one of the caves as a necropolis. In the 9th century they left the... [+]

On August 1, a dozen people from the family were in Aranguren. Two young people from Aranzadi made firsthand the excavations and works being carried out in Irulegi. This visit is highly recommended, as it reflects the dimension of the work they are doing.

Halfway, at the first... [+]

In the desert of Coahuila (Mexico), in the dunes of Bilbao, remains of a human skeleton have been found. After being studied by archaeologists, they conclude that they are between 95 and 1250 years old and that they are related to the culture of Candelaria.

The finding has been... [+]

The Roman city of Santakriz is an impressive archaeological site located in Eslava, near Sangüesa. Apparently, there was a fortified people of the Iron Age, and then the Romans settled in the same place. Juan Castrillo, himself a priest of Eslava, gave the site for the first... [+]

This winter the archaeologists of the INRAP (National Institute of Preventive Archaeological Research) have found a special necropolis in the historic centre of Auxerre (French State), a Roman cemetery for newborn babies or stillbirths. - Oh, good! The necropolis used between... [+]

Two years ago, the Catalan archaeologist Edgard Camarós, two human skulls and Cancer? He found a motif card inside a cardboard box at Cambridge University. Skulls were coming from Giga, from Egypt, and he recently published in the journal Frontiers in Medicine, his team has... [+]

York, England, 2nd century. Various structures and houses were built in the Roman city of Eboracum. Among others, they built a stone building in the present Wellington Row and placed an arch in the wall that crossed the Queen’s Hotel. Both deposits were excavated in the second... [+]