After-school activities, a missed opportunity for social cohesion

- There's a lot of talk about the segregation of students in education, but what goes to the swimming course, the football team, the dance academy? What is left every afternoon in the street, in gazteleku or at home, because it has no financial and logistical resources? What consequences does this have on the development, relations, social cohesion of children and young people? Should we not guarantee equal opportunities in after-school activities by recognising the educational and social values of organised leisure?

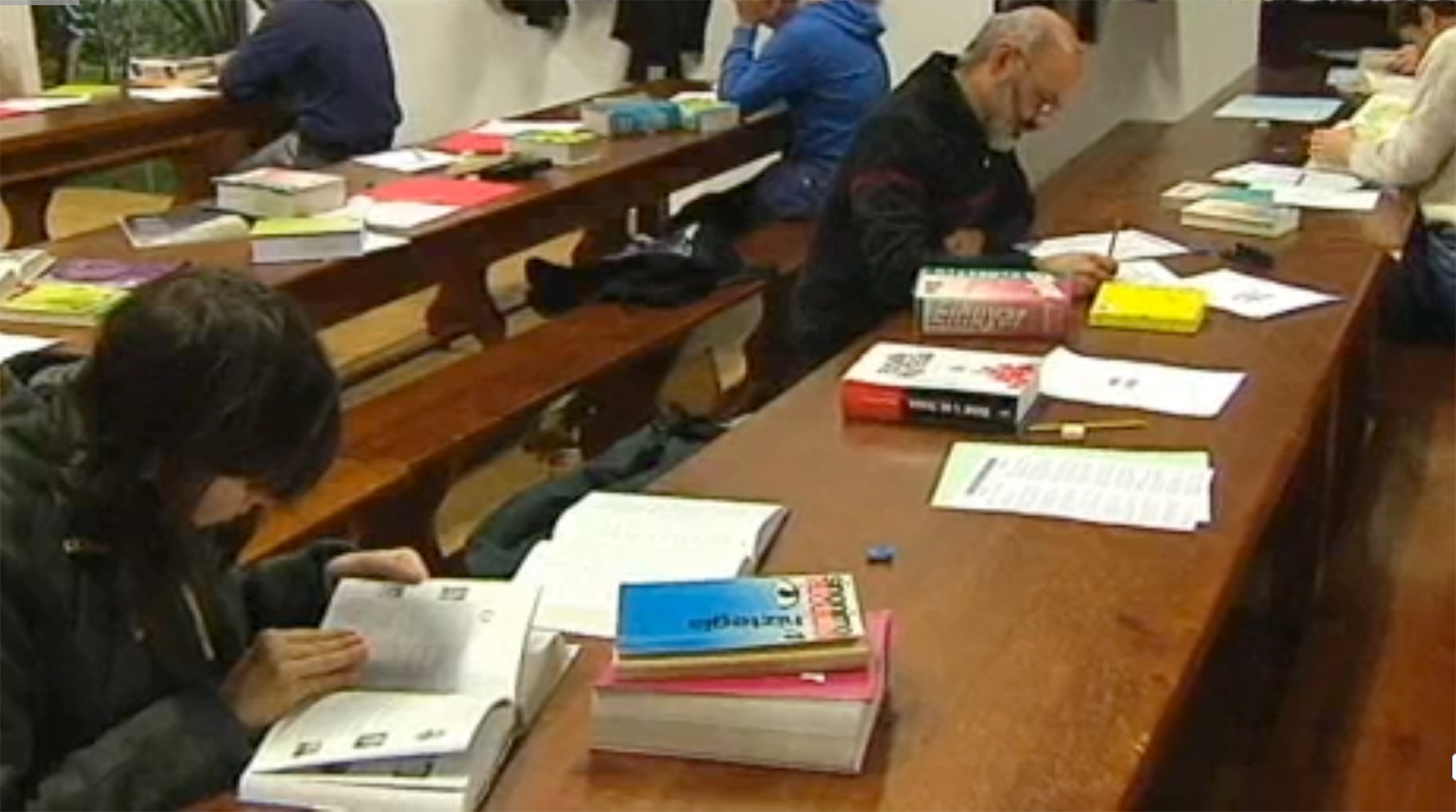

“Democratizing and universalizing participation in after-school activities that are part of education is our challenge as a country.” This was recently said by Catalan professor Gemma Ubasart. In our case, the gap in the leisure of children and young people is also evident. Amaia Bergara, a street educator from Malaga, tells us her experience in the Gazteleku: although the weekend brings together more varied profiles of young people, gazteleku is a bubble in working days, “they are young people who come because they have no other task or where to go, they are scarce, while the rest are in extra-school activities or with their family. I've talked to them many times about extracurricular activities, but most don't think about it, they don't see the possibility of doing it at home, they think it's something from another universe to go to the piano, to the solfeo, to English, to ballet ... They attend workshops, etc. If they are very cheap, no.

Bergara is clear: many of these young people would be happy to participate in the activities if they had a real chance. In summer, for example, they had a gym bonus and we were told that young people took advantage of it, but when they cut off the bonus they stopped going to the gym from morning to night. And another example to take the size of the situation: think of a young man participating in the football team who didn't have to pay, but only in the trainings, he didn't go to the weekend games because he didn't have money for equipment or to move around. In short, the economic difficulties are compounded by the fact that it is sometimes not easy to travel around the city during the week, neither the child or youth themselves nor their families.

In addition, in a single activity, two or three extracurricular activities per week and even three or four activities, with the economic cost involved. And the difference between actions, clubs, associations… is often significant (see infographic below), some are subsidized and some are not, some as basic items and others as luxury items.

The influence of friends and the environment is also an important factor when choosing activities. That is what Oihane Vicente says. It offers Basque dances and creative dance, the latter for 30-35 euros a month (a weekly one-hour session) and knows that it is an economic effort that will limit many families to encourage their children to classes. The outcome of the administrative intervention is different: “The registration at the last dance workshop I have given the City Hall was 3 euros,” explains Vicente.

Amaia Bergara: "It also means losing networks. Children don't go to football or ballet alone, for many to feel part of a day is fundamental."

In Secondary Education, extracurricular, complementary and enriching activities of formal education are an important pillar. This is confirmed by the partners in this report, so not guaranteeing equal opportunities and excluding people from these networks is discriminatory. Personal development, self-esteem, management of emotions, co-education, relationship, mutual care, deepening in the ludic, strengthening the Basque country in informal spaces… can be a unique opportunity. Extracurricular actions favor one’s own potentialities, abilities and motivations, “and being on the sidelines can mean limiting your ability and talent,” says Vicent. Sometimes, these are activities related to the academic environment, with the objective of advancing the issues taught in the school until turning the competition between parents into a vicious circle, and the conclusion is clear for those who are marginalized, who are still further behind in their academic trajectory.

It is also being left out because “participating in these groups means building new groups of friends,” says Vicente. The weight of private extracurricular activities in our society is high, many move in that bubble and many are out of it, turning those that could be a great opportunity for social cohesion into an instrument of social rupture. The view of the educating street helps to understand the importance of: “Children are not going to play football or ballet alone, something like this makes them very good, many factors can be worked, and for many it is fundamental to feel part of a team of these characteristics; it is more, sometimes it can become their second family, in their lives it acquires a great centrality, not to say in adolescence,” says Bergara. “These activities are also very important for building an orderly life. Many of the young people who move through the educational streets do not have a fixed role, they are used to being ‘alone’ since they are young, and that order, when you lose that structure, you look away from the social network, that person has difficulty finding their place, often ends up lost”.

.jpg)

How can we compensate for the imbalance?

If we want to implement the value we give them the floor, should not every child have the opportunity and the right to participate in organized leisure, taking into account the economy of each household? Should we not extend public supply, should we not set criteria for private supply so as not to exclude anyone? Indeed, it is undeniable that private associations, clubs and academies have a great primacy in the general offer, and as part of the education of children and young people, it is to be assumed that, despite being a private activity, values and foundations should be required. But the interlocutors have responded with caution: it is not easy to control what is done in the private sphere, and it is delicate for the administration to go hand in hand with them. So what do you do?

The respondents have chosen two interrelated routes: to organize more activities supported by public money for children and young people and to strengthen the after-school activities developed by the associations of parents of the centers. Lurdes Imaz, coordinator of the Association of Fathers and Mothers of Students of Euskal Herria (EHIGE), states that offering off-market activities can help overcome social imbalances: “There are municipalities that organize it punctually, but it is clear that there is little interest on the part of public institutions; often there is a lack of resources and highly qualified professionals, because the non-formal area is undervalued at the academic level”. We have been given a positive example from the Hezen Leisure Association, because they say that leisure initiatives (games, workshops, excursions...) that dynamize Family-Ola and Parquetarras are a success and attract people with different profiles. The initiative, managed by themselves, is offered by municipalities and the participation of children is free of charge thanks to the money provided by municipalities.

Bergara and Vicente put on the table an interesting key: the benefits of networking. For example, the local City Hall may be in contact with street educators, social services, gaztelekus, leisure associations and after-school activities to better target the needs of children and young people.

If the extracurricular activities carried out by the AMPAs of the centers are properly subsidized, it would be an economic offer open to all

Scholarships for after-school activities?

Faced with discrimination, it seems easier to intervene in the after-school activities organized in the school than in private clubs and academies. That is why we have been told that this is a good alternative: the child should not be moved from one place to another and if the institutions subsidise, an economic offer should be made, open to all.

But there is currently also segregation in these activities. Aitor Idigoras is in the association of parents of the school of his sons and daughters and shows us his concern: “The principle of equity and equality is present in the organization of actions, but it does not have a simple solution: we know that many families do not belong in these activities, but it is very difficult for us to know why, when it is because of economic difficulties and by another factor, and we have not invented a viable way to access this information. We also try to set the activities a maximum price, a limit, but it is not easy with all the actions, because they have a cost.”

Aitor Idigoras and Lurdes Imaz call for greater involvement of the administration to offer economic or free activities. The latter has been asked whether there are scholarships or grants to be able to participate expressly in extracurricular activities, aimed at people in a more vulnerable situation, but in general he has answered no. For the PAAs there are subsidies, and it may be a way of subsidising activities and channelling a quality economic offer, but Imaz has stressed that these public aid is very small, “EUR 800-1,200 in a two-line centre, from the Basque Government”. The picture is wider among municipalities: “Some give good support, but the processing is complex and these aids do not normally take into account students with special needs who need personalized support to be able to participate in such activities.”

From one center to the other the difference can also be large, and the offer of after-school activities is very scarce and sometimes poor, if parents, for example, do not have enough time and resources to get involved in the organization, as in centers with many families in precariousness. Idiazabal has claimed that public aid should prioritise these centres: “The City Hall should provide direct support to the schools left to the bottom, even with monitors, or if not the AMPA, for the City Hall to organize activities in those schools like the rest of the centers.”

Networking is beneficial. The town hall may be in contact with street educators, social services, gaztelekus, leisure associations and after-school activities

The street and the academy There is also a

tendency to the other end: sometimes the children point to too many things, spend many hours in guided activities, and in the end we can end up stressing children, or the children can end up not knowing what to do in free leisure, without being able to play and get bored. Experts stress the importance of balance, reserve every day a free time to play, to internalize what has been done in the day, to create, to do things at home… “We also have to give importance to free play, because today we have everything very oriented, squares and parks should regain the importance of old,” says Ainhoa Pinedo, of the Hezen association. But the imbalance is also evident: some may choose to enjoy a quieter leisure by limiting activities, but the passage of evenings down the street is an abrupt path for the most vulnerable in society.

Gertakariak igande egunsentian suertatu dira 5:00ak aldera Gasteizeko Mitika diskotekan. Hildako pertsona 31 urteko gizon bat da, eta lurraren kontra buruarekin hartutako kolpe baten ondorioz hil da, antza atezainak kolpe bat eman ostean.

At Christmas we went on holiday with our friends to Trieste (in Slovenian Trst). In it, among other monuments, we have visited the Castle of Miramar. The story of this building is curious. It was built between 1856 and 1860 by the Archduke Maximilian of the Habsburg Dynasty,... [+]