Pictures of film fragments

- Art and artistic manifestations have always been a step beyond society. That’s why some say that to legitimize and assimilate the work of a photographer one must spend a hundred years, because that’s the time that history – the patriarchal system – needs to properly read the work of these women. The Exhibition Room Kutxa Kultur Artegunea of San Sebastian works to reduce this distance, an institution that is performing an intense work to recover the work of the photographers who in its program have left the official history of art out. The tour, which began with exhibitions dedicated to the work of Berenice Abbott, Vivian Mayer and Margaret Watkins, has been stopped in the work of Ruth Orkin, an American photographer with a vocation as a filmmaker.

Ruth Orkin (Boston, 1921 - New York, 1985) grew up in Hollywood film studios, between sets for recordings, claps in the background and in the middle of the 20s actor journey, whose mother, Mary Ruby, was a silent movie actress. Perhaps because he grew up in that environment, he had the desire to become a filmmaker, to stand behind the camera and to write and direct his films. At that time, however, almost all women who worked in film stood in front of the camera, as actresses, and only a few worked in film production or assembly. It was an abrupt path for women to engage in film. Alice Guy, Lois Weber and Maya Deren were the few who managed to make their career as directors, and until recently their approach to their work has been insufficient.

In the early 1940s, Orkin decided to put aside his obstructive dream and study the photojournalism of Los Angeles City College, a trade he worked on in the coming decades. In 1943 he took the work to New York, where the most important journals of the time were, and for many of them he worked: LIFE, Look, Ladies Home Journal… traveled to Israel and Italy on behalf of LIFE magazine and captured attendees with their camera, including Ruth Orkin. Illusion of the time we will see in the exhibition.

Mary Engel, Orkin's daughter, has been taking care of, restoring, researching and publishing her mother's legacy for 37 years, to enable divulgative exhibitions like the one we have in San Sebastian. A background of hundreds of albums, negatives and contact sheets offers the opportunity to make multiple readings about Orkin’s work. In this sense, the exhibition curator, French Anne Morin, has wanted to capture in Orkin's photographs the gestures, tricks, ways of doing and methodologies that have been collected from the movies, since this is the thesis of the exhibition, although she worked with fixed images, the reading of these images could be read as a sequence of images or frames that generate movement.

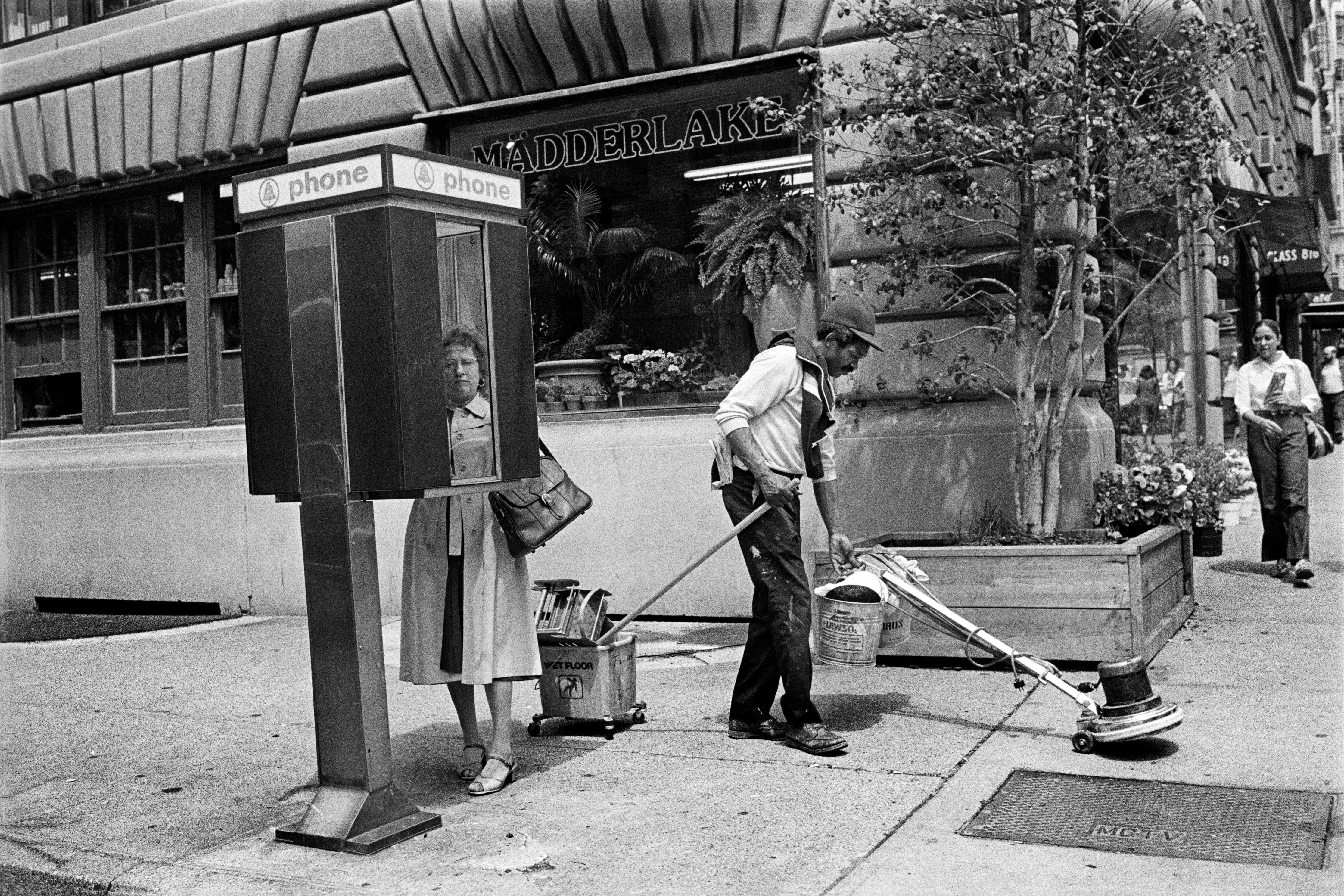

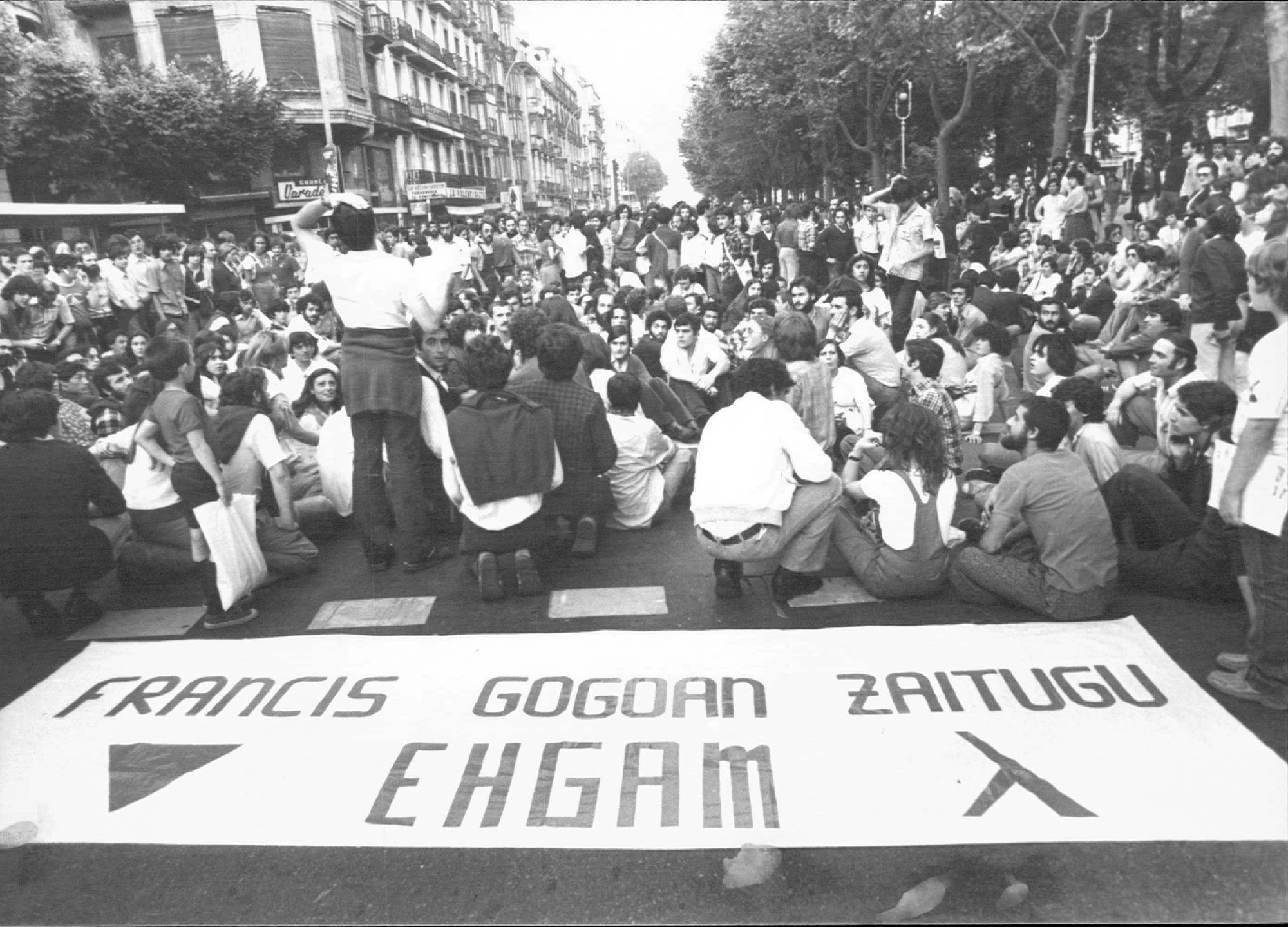

The curator has divided the exposed material into four groups, each of the approaches is an invitation to see the photographs from the perspective of cinema. Dynamic gaze is the first chapter that opens the exhibition. In it we see a lot of cenital images, the vibrant city of New York in the years after the depression, becoming the background of all of them. From the window of his house he observes a city in constant transformation and modernization, and from that height he captures census portraits of pedestrians: sailors, couples, friends crews…, marathons, manifestations and changes of clothing of nature in the passage from one time to another. Photos taken from home in Central Park are collected in A World Through My Window and More Pictures From My Window.

.jpg)

The Commissioner has chosen the idea of duplicity and unfolding for the second chapter and has made a selection of photographs really interesting when it comes to classifying the photographs made for decades: in the same photograph we will see two or three people dressed almost in the same way or performing the same movement, as consecutive frames, which could be the starting point of a film sequence. These are still images that create a narrative from the perspective of cinema. Two Women in Bathing Suits (1948) is one of the most significant.

In the exhibition we will find sequences that generate movement through a set of photographs. In this case, children reading a book on the street or pictures of three children playing cards, keeping the same frame, form a raccord, a complete sequence, which in the quick view seem to have a movement of their own. Children, children's games and gestures are portrayed in their photographs.

In 1951 he made a stay in Italy where he met Nina Lee Craig, an American student of Art History. With it, he began to make fotonovelas that became fashionable at that time, translated into film language, comparable to storyboard. American Girl in Italy (The American Girl in Italy, 1951) forms a still image narrative scene, perhaps the most famous Orkin photo series. Pulling the narrative idea, at 17 years old, Orkin made a road bike trip from Los Angeles to New York, with a medium format uniobjective Reflex 6 Pilot camera. He toured 2,000 miles by bike, visiting cities like San Francisco, Arkansas, Chicago, Boston and New York, and he presented the photo editions of these trips in a timeline of time, creating the feeling of being in a road movie.

In .jpg) 1952 Orkin married photographer and filmmaker Morris Engels. Together with him he wrote and directed his first film, Little Fugitive (The Little Fugitive, 1953), nominated for the best screenplay of the American Academy of Film Arts and Sciences and screened at the Venice Festival, winning the Silver Lion to the best director. The film, set in the New York summer, narrates the adventures of the brothers Joey and Lenny, children, with a comic and enjoyable tone. The streets of New York, the beach and the swings of Coney Island, which we see in the film, are reflected in Orkin's photographs. So the curator has chosen three sequences from this film to make the audience see what the compositions, the blueprints and the characters in their photos were like, taking them to the film afterwards. The critic extolled the film at the time and it is said that when François Truffaut rode Les Quatre Cents Coups (400 Hits, 1959), he was inspired by Little Fugitive’s spontaneous production style, and much later said that the nouvelle vague would never have been born had it not been for that film.

1952 Orkin married photographer and filmmaker Morris Engels. Together with him he wrote and directed his first film, Little Fugitive (The Little Fugitive, 1953), nominated for the best screenplay of the American Academy of Film Arts and Sciences and screened at the Venice Festival, winning the Silver Lion to the best director. The film, set in the New York summer, narrates the adventures of the brothers Joey and Lenny, children, with a comic and enjoyable tone. The streets of New York, the beach and the swings of Coney Island, which we see in the film, are reflected in Orkin's photographs. So the curator has chosen three sequences from this film to make the audience see what the compositions, the blueprints and the characters in their photos were like, taking them to the film afterwards. The critic extolled the film at the time and it is said that when François Truffaut rode Les Quatre Cents Coups (400 Hits, 1959), he was inspired by Little Fugitive’s spontaneous production style, and much later said that the nouvelle vague would never have been born had it not been for that film.

Years later, in 1955, the couple shot together the film Lovers and Lollipops, with which Ruth Orkin's dream was fulfilled. Undoubtedly, a nice summer plan is to witness those moments that Orkin captured with his camera, a time of pieces of film on this journey.